The Circular Economy: Societal Transformation or Economic Fairytale?

In recent years, the concept of the ‘Circular Economy’ has moved to the center of political and academic discourse on sustainability, industrial innovation, eco-efficiency and socio-ecological change. But what do people really mean when they talk about the Circular Economy? There are very few studies that compare and clearly differentiate the multitude of different circular economy discourses and visions. Martin Calisto Friant, PhD researcher at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, addressed this key knowledge gap by developing a typology of Circular Economy discourses, which reviews and conceptually classifies over 70 circularity concepts from the early 1950s to the present day. REVOLVE Circular sat down with him to learn more.

What were the origins of the Circular Economy, and how did it gain popularity?

The Circular Economy is nothing new. For the greatest part of humanity’s presence on Earth, we lived in circular societies where material and energy flows circulated sustainably, in harmony with the natural cycles of the earth. It is only during the industrial revolution that we broke this balance, through the creation of growth-dependent economic structures and the increasing use of fossil fuels. A new set of literature thus started to investigate the consequences of industrial capitalism for the Earth and its human and natural ecosystems. This is when the modern precursors to the Circular Economy concepts emerged, with key publications such as “the Economy of Permanence” by J.C. Kumarappa in 1945, and in the early 1970’s “Tools for Conviviality” by Ivan Illich, “Ecology as Politics” by André Gorz, “Post-scarcity Anarchism” by Murray Bookchin, “Toward a Steady-State Economy” by Herman Daly and “Small is Beautiful” by E.F. Schumacher. “The Closing Circle” by Barry Commoner in 1971, is perhaps the first book to use the metaphor of a circle to illustrate a sustainable society, where material and resource flows circulate sustainably, and are democratically redistributed to ensure social fairness and equity.

Other key precursor concepts/books from the 60s and 70s:

- The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth (Boulding, 1966)

- The Limits to Growth (Meadow’s et al. 1972)

- The entropy law and the economic process (Georgescu-Roegen, 1971)

- Ecological Design (Papanek, 1972)

- Permaculture (Mollison and Holmgren, 1978)

- Deep Ecology (Næss and Rothernberg 1989)

- Ecofeminism (D’Eaubonne, 1974)

Another key historical period was from 1990 to the early 2000s, especially with the emergence of the field of “industrial ecology”.

In the 1990’s, new Circular Economy concepts were developed:

- “industrial symbiosis”

- “biomimicry” by Janine Benyus

- “Extended Producer Responsibility” by Thomas Lindhqvist

- The Biosphere Rules by Unruh

- “industrial metabolism” by Robert Ayres and Udo Simonis

- “Eco-design /Design for environment”

- “reverse logistics”

- Cleaner Production

- Eco-industrial parks and networks

- Product Service Systems

- Closed-loop Supply Chain

- Biobased Economy / Bioeconomy

- “Industrial Symbiosis”

This literature emerged at the same time as neoliberal economic thinking; therefore, these concepts have market-driven approaches, which did not give much attention to considerations of social justice and equity. Nonetheless, they brought important insights on new technologies and innovations to recover industrial and household wastes, and to improve the environmental performance of products and services.

In the 2000s more Circular Economy concepts – with a more holistic and socially inclusive approach to consumption and production – emerged:

- “the natural step” by Karl-HenrikRobèrt“cradle to cradle” by William McDonough and Michael Braungart

- “degrowth” by Serge Latouche

- “the performance economy” by Walter Stahel

- “Buen vivir” by Latin American indigenous movements

- “Ecological swaraj” by Ashish Kothari

- “simple living” by Samuel Alexander, Ted Trainer, and Simon Ussher

- “permacircular Economy” by Christian Arnsperger and Dominique Bourg

- “symbiotic economy” by Isabelle Delannoy

- “Blue economy” by Gunter Pauli

- “Doughnut Economics” by Kate Raworth

- “The Transition Movement” by Rob Hopkins

- “Economy for the Common Good” by Christian Felber

- “Ubuntu” from South African traditional philosophy

- “Convivialism” by Alain Caillé and the convivialist movement

Considering its diverse history and the variety of related concepts, the Circular Economy can be best understood as an “umbrella concept” which combines and embraces many key elements of sustainability thinking. To further explore its conceptual richness and evolution, I invite your readers to have a look at our interactive timeline of circularity thinking: http://cresting.hull.ac.uk/impact/circularity-timeline/

There is a key contrast between the way that academics understand circularity and how businesses and governments are implementing it.

Your ongoing research has resulted in the identification of four main “circularity discourse types” – what are they and what circular vision do they propose?

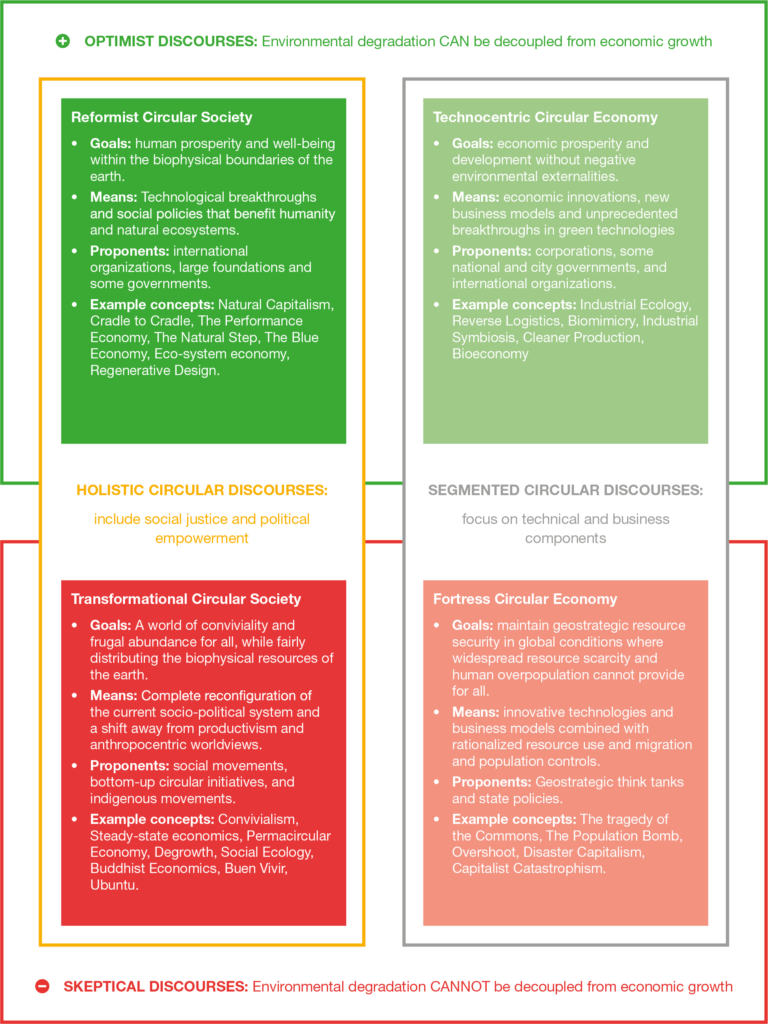

My research led to the development of a 2 × 2 circularity discourse typology to help navigate the rich history and diversity of Circular Economy concepts and ideas. This typology divides circularity discourses in two main criteria: first, it distinguishes segmented discourses, which focus on the technical and business components of circularity, from holistic discourses, which include social justice and political empowerment. Second, it divides optimist and skeptical perspectives regarding the possibility of decoupling environmental degradation from economic growth, so-called eco-economic decoupling. Different combinations of these two criteria lead to four main circularity discourse types.

Reformist Circular Society – optimist and holistic – discourses seek to create a sustainable circular future through a combination of innovative business models, social policies and technological breakthroughs. Technocentric Circular Economy – optimist and segmented – discourses seek to reconcile economic development with ecological sustainability through innovative business models and technologies. Transformational Circular Society – skeptical and holistic – discourses seek to re-localize, democratize, and redistribute power, wealth and knowledge to create a sustainable post-capitalist future where humanity and nature live in mutual harmony. Fortress Circular Economy – skeptical and segmented discourses seek to ensure biophysical stability and geostrategic resource security through top-down migration controls, technological innovations and economic rationalism.

Which is the most prominent circular discourse? Who uses which?

By far the most prominent discourse type is Technocentric Circular Economy. Our analysis of 120 Circular Economy definitions has found that eighty-four percent fall in this discourse type. Technocentric Circular Economy discourses are particularly widespread in government policies as well as in business consultancies and corporate circular economy strategies. For instance, in our recent academic analysis of the EU’s implementation of the circular economy, we have found that the Commission’s policies follow a Technocentric Circular Economy approach, which focuses on technical solutions and market innovations while disregarding social justice and equity. Their focus on technocentric approaches to circularity is at odds with the academic background, history and diversity of circularity thinking. In fact, our research has found that the majority of circularity concepts from the literature fall in the Transformational or Reformist Circular Society discourse types. There is therefore a key contrast between the way that academics understand circularity and how businesses and governments are implementing it.

A Circular Society not only circulates material and energy resources, but also circulates wealth, power, knowledge, and technology in radically democratic and redistributive manners.

As a response to the dominance of technocentric propositions, there is a rising movement promoting a holistic Circular Society vision, especially in European civil society sectors. Utrecht University and the Dutch Degrowth Platform have organized a Circular Society Symposium in May 2020; and two Circular Society Forums have been organized by the Hans Sauer Foundation and TU Berlin in 2020 and 2021. These Circular Society visions are gaining greater support, especially from those which have criticized mainstream Circular Economy propositions for focusing too much on economic growth and competitiveness and too little on social and environmental justice. Indeed, many see hegemonic circular economy propositions as forms of greenwashing, which create the illusion that “green technologies” will allow us to overcome biophysical limits of the Earth and continue growing our economies forever. Yet, there is now a clear academic consensus showing that the decoupling of economic growth from environmental degradation is impossible and this technocentric approach to the ecological crisis is thus nothing more than a Circular Economy “fairy tale”.

If the circular economy debate remains stuck in “fairy tales” of “green growth” and doesn’t embrace a strong social justice agenda, it will lose its social appeal and systemic validity, especially considering the rising inequalities and social injustices brought by over thirty years of neoliberal globalization.

As we are learning from you how different stakeholders use and convey substantially different “Circular Economies”: is that good news or bad news?

Conceptual diversity is, in itself, not a problem. The issue is if one discourse dominates the others and does not allow for a plural democratic debate to occur on the topic. We now see a situation where governments and businesses only listen to a depoliticized and uncontroversial Circular Economy discourse, that does not address fundamental issues regarding social equity, political empowerment, and the biophysical limits to economic growth. This influences the debate and prevents a plural, open and fair discussion to occur regarding what circular future we want and how we want to get there. It means that we are not openly talking about key issues such as who pays for the transition, who owns the technologies and innovations and who governs and directs this transformation. This lack of open discussion can easily lead to the imposition of a technocentric circular future – against the wishes and needs of most people. Research on citizen perspectives on circularity has indeed found that most people and civil society organizations have a more holistic and socially inclusive vision than what governments and companies are implementing. A recent survey in France, for example, found that fifty-four percent of French citizens prefer a degrowth-oriented ecological transition than a green-growth one; another survey found similar results with fifty-five percent of French people preferring a “sufficiency oriented ” rather than a “techno-liberal” (15%) or a “traditionalist” (30%) ecological transition. Thus, while technocentric circular economy discourses are a key part of the transition, as they can envision innovative technological solutions, they should not dominate the debate, especially when many other discourses with wide-spread social support exist.

How do you see the future development of the Circular Economy concept?

The Circular Economy is in what some researchers call a “validity challenge” period – this means that it must confront its key challenges and limitations to remain relevant, or it might be rejected as a new form of corporate greenwashing. To prevent this, we must shift our debate from visions of a Circular Economy to those of a holistic Circular Society. A Circular Society not only circulates material and energy resources, but also circulates wealth, power, knowledge, and technology in radically democratic and redistributive manners.

Systemic socio-political change will be necessary, whether we like it or not.

If the circular economy debate remains stuck in “fairy tales” of “green growth” and doesn’t embrace a strong social justice agenda, it will lose its social appeal and systemic validity, especially considering the rising inequalities and social injustices brought by over thirty years of neoliberal globalization. As we continue to overshoot the ecological limits of the biosphere, and the impacts of climate change rise year after year, it will become harder and harder to argue for failed technocentric solutions. Systemic socio-political change will be necessary, whether we like it or not. Yet, faced with an impending socio-ecological collapse, visions of a Fortress Circular Economy will also become more and more appealing. Indeed, as we confront stronger natural disasters and shortages of key natural resources, many conservative voices will start arguing for greater nationalism and top-down control over resources and populations. As an alternative to this, we must build alliances amongst social movements, academics and civil-society organizations across the world to propose an appealing alternative: a fair, democratic, de-colonial and sustainable Circular Society where nature and humans live in mutual harmony.