Melbourne: Towards Zero Emissions by 2020

Aiming at zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, Melbourne has put itself on the map as the next sustainability hub. In order to achieve this ambitious target, major efforts will have to come from Melbourne’s government, private sector, and citizens. Mitigation policies in Melbourne heavily focus on changes related to energy use. Energy savings, energy efficiency, and decarbonizing the energy supply are indispensable for transposing the zero net emissions plan to concrete reality.

Melbourne

Melbourne – the capital of the State of Victoria – is a coastal city in Southeast Australia. The metropolitan area has nearly 4 million residents, covering an area of 7,693.7 km2. The City of Melbourne (number 30 on map 3) represents only a small part of the whole urban agglomeration (37.6 km2) and has 93,105 residents. However, it concentrates a wide range of activities. As a consequence, the City of Melbourne has 765,000 city users daily1.

As the majority of Australians live in a small number of cities, a unique opportunity exists to generate societal change through action in a limited number of places. In Victoria, 80 percent of the population lives within metropolitan Melbourne. Given the high number of city users, the City of Melbourne can reach a significant amount of people through its projects. In addition, the Municipal Association of Victoria supports all municipalities in the State of Victoria to establish solid environmental policies and practices. Being a state capital, the City of Melbourne can play an exemplary role.

Because it has relatively little direct control over emissions that result from activities that take place within its territory, it has opted to show municipal leadership in order to influence and stimulate change by other public and private actors and citizens (City of Melbourne 2008b, 31).

Climate Change Policy

The lack of a progressive federal climate change policy has stimulated climate change policy-making at the state and municipal level (Bulkeley and Schroeder 2009), not the least because Australia is already experiencing the consequences of climate change. The prediction of sea level rise and more intense storms makes adaptation and mitigation strategies invaluable for Melbourne (City of Melbourne 2008a).

In terms of adaptation, an extensive water policy – Total watermark-City as catchment (2008) – has been introduced that should transform Melbourne into a water sensitive city. With regard to mitigation, energy is a crucial policy pillar. Having the energy issue already on the table in the 1990s, participation in the ICLEI Cities for Climate Protection program (1997/1998) and the adoption of Zero Net Emissions by 2020 – A roadmap to a climate neutral city (2002/2003) reflected an acceleration of action in this domain (Bulkeley and Schroeder 2009). The first zero net emissions strategy focused on leading edge design, greening the power supply, and offsetting. The 2008 revision has the following strategies: commercial, residential, passenger transport, and decarbonizing the energy supply.

In the commercial sector, the aim is to make buildings more energy efficient. Old buildings will be retrofitted and higher sustainability standards are introduced for new buildings. People’s homes also have to become more energy efficient and better insulated. An increased awareness about water and energy use should lead to significant behavioral change amongst citizens.

In the transportation sector, cleaner public and private transport is needed and investments in infrastructure should stimulate people to cycle more. The implementation of renewable energy should contribute to decarbonizing the energy

supply (City of Melbourne 2008b). The following sections illustrate these strategies with concrete examples and discuss how pilot projects can make the City of Melbourne a laboratory from which to learn and replicate.

Building Energy Efficiency

The huge amounts of energy they consume make office buildings an obvious target in the zero net emissions strategy. 25 percent of office space in Australia is located in Melbourne. Thus, if office buildings in Melbourne become more sustainable, and in case this is replicated in Sydney, Brisbane, and Perth, you would basically have dealt with that sector for the whole of Australia.

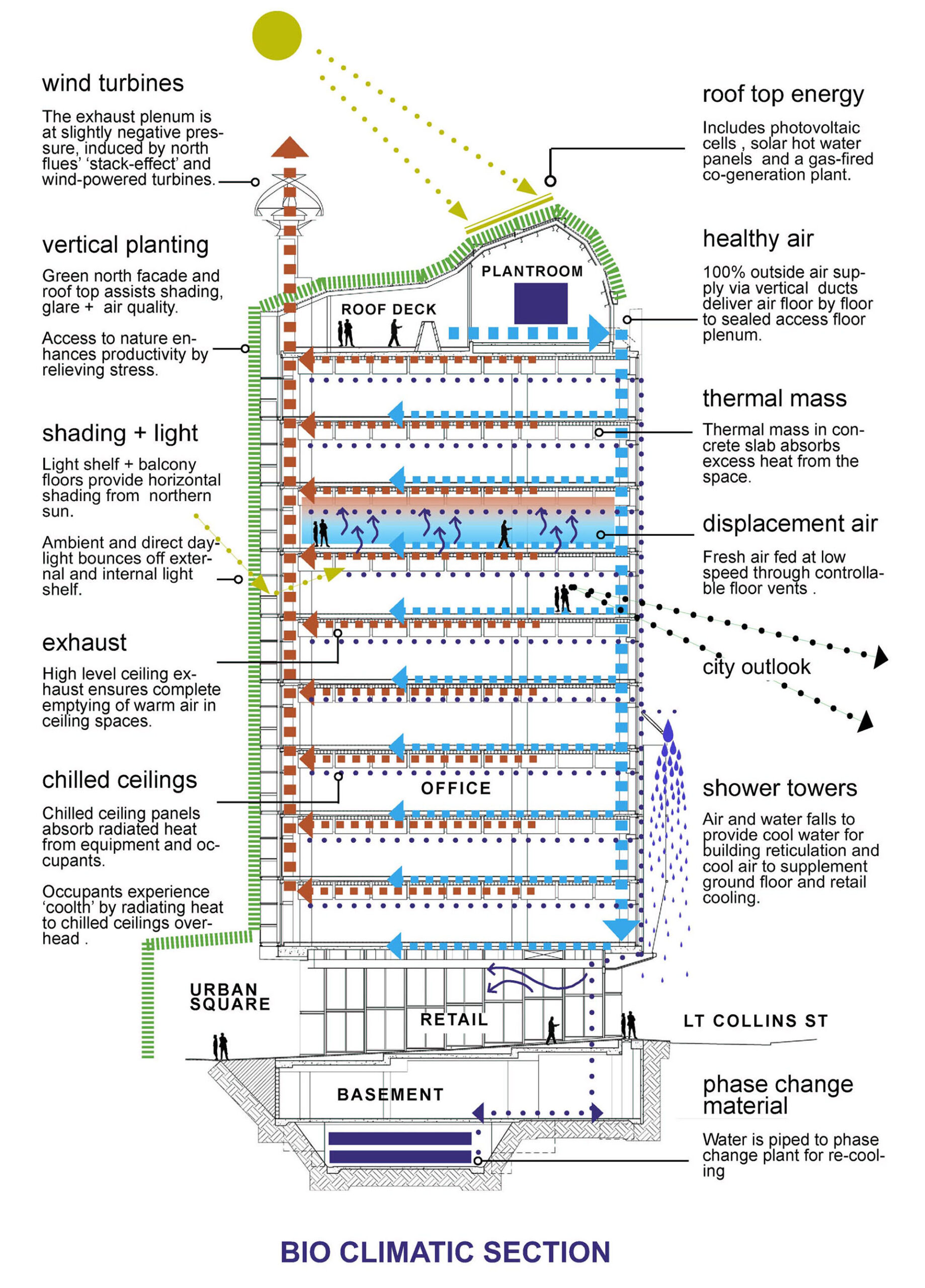

With regard to new office buildings, the City of Melbourne demonstrated the way to move forward by constructing Council House 2 (CH2). The building is designed to conserve energy and water and offers a high quality internal environment. Figure 1 shows how the building functions. The value of CH2, apart from the generated savings, is that it shows what is possible in terms of green buildings. As such, it is the most powerful form of information. A range of other initiatives surrounded the construction of CH2, which made the project even more valuable. Prior to CH2, there had been an experiment with a smaller building to produce a green building (60L Green Building), which opened in 2002. Around that time, the council was about to decide to build a new office building and the Green Building Council of Australia was being formed. The Green Building Council of Australia used the design of CH2 as its testing ground for the rating system it had created. This allowed designers to learn from that rating system and when the rating system was announced, there was an existing building that ranked at the top end. In other words, CH2 functioned as a laboratory that informed the green building rating system, planning regulations, and stimulated the development of the local green building industry. It also facilitated the approval to start other initiatives in the larger Melbourne metropolitan area. CH2 is recognized as a best practice by C40, a group of 40 large cities that want to catalyze action on climate change3. Through the best practices database of C40 the City of Melbourne can share its experience with other cities around the world. This opens the door for an even wider sphere of influence.

Existing office buildings are stimulated to increase their energy efficiency and save on the use of water. The City of Melbourne – through the 1200 Buildings Program – helps owners of commercial buildings to find funding for retrofitting. The Council itself has a contract with Honeywell to retrofit 13 municipal buildings, which is the result of being part of C40 and working with the Clinton Climate Initiative, which has brought together energy service companies and financial institutions in order to assist cities to make their buildings more energy efficient. A retrofit that has been realized prior to the 1200 Buildings Program is the Szencorp building. It is a brilliant example that shows how a typical existing suburban office building can become a sustainable building4. Szencorp is specialized in water and energy efficiency in the building sector and uses the 3 For more information on C40, see: www.C40cities.org. 4 For a virtual tour visit: http:/ www.ourgreenoffice.com/Video/flythrough.html experience of retrofitting its own offices as an example for customers. As such, Szencorp has set a benchmark for sustainable buildings. There is a holistic vision behind the project, not only focusing on savings in energy and water, but also reducing waste, developing renewable energy for own use, stimulating employees to use alternative transport modes, and providing a good working environment. The Szencorp building continues to achieve better water and energy savings every year and has obtained several awards and high performance ratings according to the standards of the National Australian Built Environment Rating System and the Green Building Council of Australia. Data on in its achievements are made public on the company’s Web site5.

Urban Transport: New Thinking About Mobility

The Melbourne metropolitan area is characterized by urban sprawl. People living outside of the City of Melbourne commute most often by car: congestion and emissions from burning fossil fuels ensue. The City of Melbourne is stimulating people to move to the city center again, public and private vehicles will have to become cleaner, and everyone is encouraged to use less polluting modes of transport.

Getting more people on bicycles is one of the strategies to change the current mobility pattern. Inspired by successful initiatives in Barcelona and Paris, the City of Melbourne launched Bike Share. There are 50 bicycle stations with 600 bikes in the Central Business District, which can be used for short trips when you have an annual subscription or bought a daily or weekly pass. This system provides people with an alternative transport mode and should lessen the amount of cars circulating in the city6.

An interesting idea that has been launched at the C40/Arup UrbanLife workshop in Melbourne (March 2010) is an integrated mobility system. The workshop brought together staff of the City’s administration and professionals of Arup – a global consulting firm of designers, planners, engineers, and technical experts. Arup has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with C40 to deliver workshops in six C40 cities. Each of the workshops addresses an issue identified by the respective city and linked to the reduction of carbon emissions. The intention of the workshop in Melbourne was to look at ways in which technology and design could be used to make the city more sustainable. One project would be to create a real-time information system (with information at bus and tram stops, on personal devices, at places where many people meet etc.) that enables citizens to know which modes of transport are available to undertake their journey. Having real-time information available would open people’s minds, they could combine multiple modes of transport, and this could then lower car use and increase the use of different types of public transport.

Decarbonizing Energy Supply

Stimulating the provision and use of renewable energy is an important aspect in order to decarbonize the energy supply. The municipal government is showing leadership in this regard. In 2009-10, 33 percent of the energy it used was renewable energy7. The CH2 building has six turbines and the City of Melbourne – together with the Australian Greenhouse Office – funded the Queen Victoria Market solar energy system. This system can generate up to 252,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity each year and provides energy for the surrounding community. The performance of the installation is displayed on an information board outside of the market, which can rise awareness about energy production and use8.

A Green-City Mode

Although some might conceive the examples just described solely as individual success stories, more is at stake. Since cities often function as laboratories, pilot projects in these places allow experimenting with innovative technologies, which leads to learning. Projects and policies can then be adapted, improved, and replicated elsewhere. Pilot projects can serve to find support for broader changes since they show what is possible. What happens in a city like Melbourne can then be an example for other municipalities in the region or even for governments. Further, the increasing importance of inter-city networks of cooperation makes it possible to even have an exemplary function for cities overseas. Such networks organize meetings where city officials from around the world exchange knowledge, experiences, and best practices. These networks have Web sites where cities can find all necessary information about successful practices and policies. Being involved in several city networks for global environmental governance, like ICLEI and C40, Melbourne has been able to build relations with other cities, learn from these cities, and share its own knowledge with them. Melbourne is already a green-city model.

References

Bulkeley, Harriet and Schroeder, Heike. 2009.

Governing climate change post-2012: the role of global cities – Melbourne. Working Paper 138. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

Available at: http://www.tyndall.ac.uk/tyndall-publications/working-paper/2009/climate-change-post-2012-role-global-cities-melbourne.

City of Melbourne. 2008a.

Total watermark-City as catchment.

Available at: http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/AboutCouncil/PlansandPublications/strategies/Pages/Environmentalpolicies.aspx.

City of Melbourne. 2008b.

Zero net emissions by 2020 – Strategy update.

Available at: http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/AboutCouncil/PlansandPublications/strategies/Pages/Environmentalpolicies.aspx.