Fuel of the Future

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas (mainly methane, CH4 ) that has been cooled and converted to a liquid at very low temperatures (less than -160°C). This condensing process removes sulfur and water, and makes storage and transport easier by trucks, railway tankers and specially built ships known as LNG carriers. LNG occupies less volume than compressed natural gas (CNG), with an energy density 2.4 times higher than CNG and 60% higher than diesel fuel. While pipelines are expensive and difficult to build, LNG transport is cost-efficient over long distances and as a result geostrategic dynamics will intensify over the extraction and global trade of LNG.

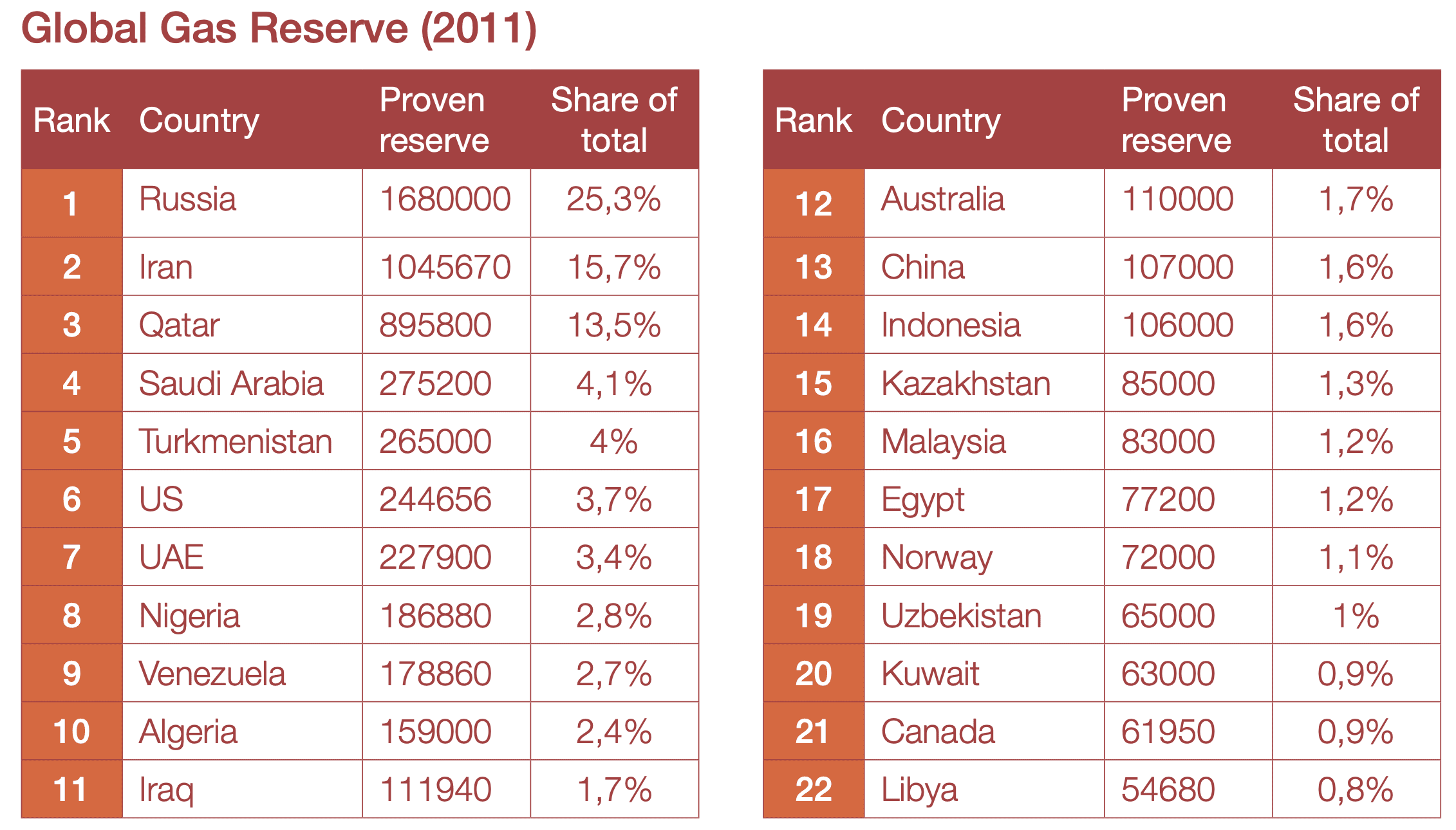

Qatar ranks among the major oil-producing countries with reserves worth nearly 900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas – third only to Russia and Iran. This small peninsula is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), with companies such as Qatargas and RasGas being the world’s leading LNG producers and suppliers. These two companies reached a record production capacity of 77 million tons per year in December 2010, with an average since then of 77.4 million tons each year. Since 2012, about 25% of the world’s LNG exports come from Qatar, according to Qatar is Booming.

Qatar’s principal gas export destinations are Japan (32%), South Korea (15%) and Singapore (10%), with demand increasing sharply, especially in China, India, and the fast-growing economies of South East Asia. In developing partnerships with other world oil giants, Qatar is expected to take further definitive measures to maintain its position as the world’s #1 LNG exporter. Although it is not unusual for great distances to divide oil and natural gas producing countries from their clients, considering the distances involved and reduced LNG transport costs, these large and lucrative demand-driven markets may be tempted by other potential suppliers such as Australia that are closer to home.

Australia and FLNG

Qatar’s predominance as the world’s leading LNG supplier is being challenged by Australia which is expected within the next five years to compete seriously in the global market. While Qatar’s output is unlikely to increase significantly in the near future, Australia’s liquefaction capacity of about 20 million tons in 2011 is expected to reach 124 million tons by 2017. This colossal increase has been made possible by the discovery of important offshore reserves and the government’s support for the industry.

Another important dimension to the future of LNG is the innovative Floating Liquefied Natural Gas (FLNG) technology. Although FLNG is still at a developmental stage, it is expected to be the game-changer for the industry. Floating above an offshore natural gas field, theoretically the facility will produce, liquefy, store and transfer LNG from its sea location directly to markets. This presents some advantages: avoiding the construction of pipelines to pump gas to shore and the possibility to assemble the plant in more cost-effective overseas sites. FLNG also addresses the lack of onshore land access thereby decreasing environmental effects.

In the short-term, only major companies, such as Shell, have the resources to take the risks involved in FLNG technology. After years of research and development, Shell announced a plan to invest $500 million in a FLNG project at Australia’s Prelude field. The project has a processing capacity of 3.6 million tons and is expected to start operating by 2017, according to Gas World. Accounting for 10% of LNG produced globally in the near future, FLNG is extracted from offshore basins, which is around 40% less expensive than from onshore natural gas projects. This is a crucial advantage for Australia.

To optimize this profitable opportunity, Australia needs to act quickly to not be surpassed by an increasingly competi- tive market. Opposition by state govern- ments to FLNG, due to the fear of losing economic benefits by processing gas offshore, can complicate the industry’s development and discourage investment in the country. A problem also lies in the lack of a sufficiently skilled workforce capable of meeting increased demand. If costs in Australia rise too much, oil and gas companies could aim their invest- ments toward constructing FLNG facilities in the Gulf of Mexico or East Africa.

Blue Fuel Market Competition

Australia is one of many emerging competitors to Qatar’s dominance of the global LNG industry. The United States has been traditionally on the demand-side of the gas market, but has experienced a reversal in its position and is expected to become a major LNG consumer and exporter. The reason is not legislative or economic, but rather due to technological improvements in “fracking” (the extraction of shale gas) with the potential to increase domestic supplies and to export excess production.

Shale gas production has increased so rapidly that there are problems in storage capacity. In 2007, 36 billion cubic meters of shale gas were extracted and in 2010

output more than quadrupled to 151 billion. In April 2012, the U.S. Department of Energy gave permission for the construction of the country’s first liquefaction and export facility for natural gas. A majority of LNG terminals in the U.S. will be constructed in the Gulf of Mexico, which is rather controversial in light of the major 2010 BP drilling oil spill. Participants in this “gas rush” include Exxon Mobil, Chesapeake, Southwestern Energy, Midstream Companies, Cheniere Energy, Kinder Morgan and Enterprise Product Partners.

However, data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration ( EIA ) shows that U.S. natural gas production levelled off in late 2011. This is also the case for shale gas, despite its dynamic growth in the last few years. According to projections made by the EIA in its Annual Energy Outlook 2013 Early Release, production will grow again after 2015 with total U.S. dry natural gas production in 2040 set to reach nearly

35 trillion cubic feet, from less than 25 in 2012. The report shows that production will surpass consumption by 2020 and will stimulate exportation. At the end of 2012, the price of gas hovered around the $3.25 mark but must rise above $4.00 to be considered profitable enough to attract investments. It is not surprising that production in the U.S. has levelled off. If it had continued to increase at the same rate, prices would have plummeted due to such huge supply. There was a warning sign on April 20, 2012, when the market value of gas was $1.82.

Since 2012, about 25% of the world’s LNG exports come from Qatar.

Projections for increases in production result from the expansion of producers in areas of the United States. Since 2007, extensive growth in production has been seen in Oklahoma and Arkansas, not to mention the huge reserves already exploited in Texas and Louisiana. The Marcellus formation, stretching from New York to West Virginia, holds nearly half of U.S. natural gas reserves and will receive massive investments according to a 2012 report from Standard & Poor’s. A University of Wyoming report indicated that activity on the Marcellus formation boosted the economy of West Virginia by $1.3 billion in 2009, creating close to 23,000 jobs. In the current context of austerity, job creation and the demand for economic growth, the U.S. government sees this as a “golden” opportunity.

Other countries in the LNG business include Russia, Iran, and Malaysia – all of which have important natural gas reserves that would not hesitate to extend their business to the lucrative and energy-hungry Asian markets. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Nigeria also have strong LNG-oriented ambitions. Colossal China is proceeding to exploit and extract natural gas by drilling wells in the region of Sichuan, which has potentially around 30 trillion cubic meters of shale gas reserves. Even in import-dependent Europe, countries such as the UK and Poland, in particular, are advocating for the liquefaction of shale gas. According to “World Shale Gas Resources” ( U.S. EIA, April 2011 ), Poland’s potential could house Europe’s largest shale gas reserves of about 22.45 trillion cubic meters.

The global gas market is set to become more competitive, driving prices down

With demand from the Pacific Basin expected to rise from 120 million metric tons per year to 241 million in 2020, the LNG market is becoming more attractive. However, increasing competition could be problematic for global gas prices. The price of natural gas depends on the local market’s supply and is not set internationally like oil. For this reason, countries that have large reserves of gas, such as the United States, Russia, Canada, Australia and Qatar, have low gas prices, while the opposite is true for importing countries in Europe and Asia. Producers can make relative profits by exporting LNG to countries where the price is several times higher than at a domestic level while also taking into account the cost of drilling. However, if some major importers turn into self-sufficient producers, this could cause problems for countries whose main export is the so-called “blue-fuel” of LNG.

The world of natural gas and LNG has always been a high stakes game. Traditional exporters have enjoyed consistent demand from foreign markets requiring the resource to sustain their energy consumption. With the increase in environmentally-minded technological developments in Europe and new forces entering the market, it would be ill-advised to consider a conservative point of view in today’s world.

Australia’s liquefaction capacity of 20 million tons in 2011 is expected to reach 124 million tons by 2017

With the U.S. looking to increase its oil and gas production and new reserves being discovered in Australia and Poland, many demand markets might turn into suppliers. For countries like Qatar, the right tactic is to consolidate its position in South East Asia and expand to other developing markets hungry for energy. One thing is certain: the global gas market is set to become more competitive, driving prices down and allowing import-dependent countries to diversify their suppliers.

In terms of energy security, many would welcome safer imports from the U.S., Australia or Poland in comparison from Russia or the Gulf countries. The development of renewable energy would suffer at the tempting hands of the cheap and abundant natural gas option. Natural gas has been seen as a “transition fuel” to the “green future” dominated by renewables. The moratorium on the fracking process in France, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria illustrates that these countries will not allow the environmental damage that comes from extracting shale gas in their countries. However, if energy demands continue to rise, this sentiment may not preclude them from buying the blue fuel from other countries that do drill for shale gas.