Easy Does It: Regulating Renewables in Spain

The Spanish energy system is and has been a matter of priorities between moving towards a new economic model and conserving the status quo of the current oligopoly system of utility companies in Spain. Renewables are and have been seen as intruders in the archaic system and as such a clear and present threat. How did we get to where we are? Why is the Spanish FIT system a disaster?

The easiest way to have prevented the disaster of the 2007 Spanish renewable energy feed-in-tariff (FIT) system would have been for then energy minister to approve a subsequent remuneration system. Considering the bluntness with which that minister ignored very direct signals from the office of the state attorney and the former National Energy Commission (Comisión Nacional de Energía – CNE), and the national energy regulator in the dubious file of Competition Transition Costs (CTC) overcompensation (now subject to investigation by the European Commission), the issue is probably not due to a lack of insight.

Pablo Neruda, Chilean poet

You can cut all the flowers but you cannot stop spring.

Feed-in-Tariff

A feed-in tariff (FIT) is an energy supply policy that promotes the rapid deployment of renewable energy resources. A FIT offers a guarantee of payments to renewable energy developers for the electricity they produce. Payments can be composed of electricity alone or of electricity bundled with renewable energy certificates. These payments are generally awarded as long-term contracts set over a period of 15-20 years.

FIT policies are successful around the world, notably in Europe. Currently there are six U.S. states (California, Hawaii, Maine, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) that mandate FITs or similar programs. A few other states also have utilities with voluntary FITs. There is growing interest in FIT programs in the United States especially as evidence mounts about their effectiveness as framework for promoting renewable energy development and job creation.

FIT policies can be implemented to support renewable technologies including: wind, photovoltaics (PV), solar thermal, geothermal, biogas, biomass, fuel cells, tidal and wave power.

Some of the benefits and impacts of FIT policies include:

- The rapid renewable energy development seen in jurisdictions with FIT policies has helped reduce the environmental impacts of electricity generation, while providing valuable air quality and other environmental benefits.

- Fixed prices created by FITs for renewable energy sources can also help stabilize electricity rates which can entice new business and attract new investment.

- Due to the guaranteed terms and low barriers to entry offered by FIT policies, they have been highly successful at driving economic development and job creation.

- Data from countries like Germany and Spain (previously) demonstrate that well-designed FIT policies can positively impact job creation and economic growth. A growing body of evidence from Europe and Ontario, Canada demonstrates that FIT policies have on average fostered more rapid RE project development than other policy mechanisms.

Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), USA.

The FIT disaster resulted in a multitude of lawsuits, including 27 international arbitration procedures, along with numerous complaints before the European Commission against Spain, concerning its electricity sector. This resulted in countless court cases and catastrophic consequences to those affiliated with this regulatory crisis.

In 2004, the governing Popular Party (Partido Popular – PP) approved legislation RD 436/2004, giving way to an overhauled FIT scheme that would boost the wind energy capacity of the country. The FIT was designed as a percentage value of an “average regulated tariff”, which operated as a “pegged” basket of values – amongst others the oil price.

This became a serious threat a few years later when emergency measures were taken by the subsequent Spanish Socialist Workers Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español – PSOE), resulting in the redesigning of the scheme through legislation RD 661/2007. This did not imply a cutback since the future returns under RD 436/2004 were still broadly respected. What was not foreseen was a dynamic FIT for photovoltaics (PV) that were still evolving in the system. The applicable FIT at the time was petrified, lacking foresight into future changes.

In 2007, after the RD661 scheme, events escalated due to another mistake by the Ministry of Energy: the regulation foresaw a 12-month notice within which participants in the system could still participate, but the energy ministry did nothing to approve a new scheme, which was not in place until well after its expiration. This created tremendous pressure on any participant with any stranded costs in PV projects around Spain to connect to the grid before expiry of the notice period, since any other action would put these costs seriously at risk.

Another error was that the ministry did not limit the amount of PV connected to the grid on a first-come first-serve basis, nor did the ministry do anything else. It took more than two years for the State to act, and when it did, it did so without the precision required. The minister punished the sector for reacting to an arbitrary and discriminatory cutback.

It was the new PP government that took over at the end of 2011 and abstained from voting on their predecessor’s cutbacks. Sentiment was that legal certainty would be restored in the country. The unfolding reality of PP thinking on renewables proved to be quite the contrary. The first regulatory act of the new government was a moratorium on all renewable energy projects making a jump from the frying pan into the fire.

The motivation for the initial cutback was wrong: the tariff deficit in Spain is caused by an artificial separation of the liberalization process in which regulated costs are separated from production costs. This separation is artificial because some regulated costs are for productive units, such as the FIT and CTCs – these CTCs represent a heavy overcompensation, and should have been settled by the government in the first cutbacks.

The regulator may not recognize or properly estimate all of the regulated costs, like CTC’s, and for that reason a regulatory deficit appears. This deficit was aggravated by the economic crisis, and its effect was thought to flatten out as soon as the demand in the electricity sector would recover.

The overcompensation of the CTC’s was repeatedly addressed by the National Energy Commission and argued by the State Attorney’s office to be legally claimable to the oligopoly. The amount would have been globally sufficient to cover the first cutbacks to the deployment of renewable energies. The CTC file is now under investigation partly because the Spanish Platform for a New Energy Model has complained about this in a lengthy document. We are optimistic that the European Commission will open a formal investigation.

Legal certainty needs to be established to develop the new

emerging energy model.

Bad Regulation and Bankruptcy

After the moratorium of January 2012, the PP approved an environmental tax that – ironically – taxes the environment, in a global setting where generally the opposite is meant to be done. A year later, Mr. Soria (Minister of Industry) and Mr. Nadal (Energy Secretary of State) designed a new FIT system which replaced the previous system.

Two details are important here: the moratorium is still in place, and therefore the new system does not apply to new installations; and second, the new system replaced the old system by means of a tiny transitional clause for all installations connected to the grid thereby creating another severe cutback, this time for all renewable technologies. The new system renders these assets toxic, with cutbacks of up to 50% of the FIT these assets were granted originally.

Bad regulation has given way to thousands of Spanish court cases, in – and it is worth repeating – as many as 27 international arbitration procedures and a multitude of complaints before the European Commission and the Petitions Committee of the European Parliament. All these dossiers have one thing in common: they are directed towards the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in Luxembourg. These cases may reach the CJEU either by preliminary Ruling or the European Commission.

Both liberalization of the electricity sectors, as well as its renewable energy involvement in Member States stems from EU regulation. Subsequently, national regulations must meet the requirements set out in the EU policy instruments affecting them and the general principles of EU law. This was expressed clearly in the IBV case of 2013 (C-195/12 – IBV & Cie).

Other developments show that EU law can also affect international arbitration cases, in a different manner than seen this year. The Micula case (SA.38517 Micula vs. Romania (ICSID arbitration award) shows that winning an arbitration and executing the arbitration award may well be very different issues. It now seems that the European Commission is likely to contest any intent of executing an arbitration award in Member States as unlawful state aid.

While of course the situation of legal uncertainty and creeping expropriation is terrible to anybody, on a personal investment level, or on an institutional investment level, as we saw, some are in the relatively comfortable position of bankability. Others are not. Individual investors with typical 100 kW PV installations are simply ruined. These people generally have collateralized their installations with their habitual residence, as project finance generally was not available for them. These families risk losing their homes if they cannot generate sufficient income for debt servicing with their banks. Many of them have had to accept losing their entire investment to the banks in order not to lose their homes, and thus are left without their savings. For these people, the direct call made by the State in the early years of the last decade, promising a safe return backed by the Official Gazette has left them without their pensions.

The End of the Tunnel?

Just before Christmas 2015, general elections will be held in Spain. Their outcome is highly contested. Litigation would have to be brought to a successful end in order to provide for the damage suffered by clients during the prohibition years of the PSOE and PP, and most of all to set limits to regulatory arbitrariness and discretionary power in general in an EU law-regulated sector. Legal certainty needs to be established to provide the future development of this sector. Renewable energies – in particular solar power – are showing sharply declining costs.

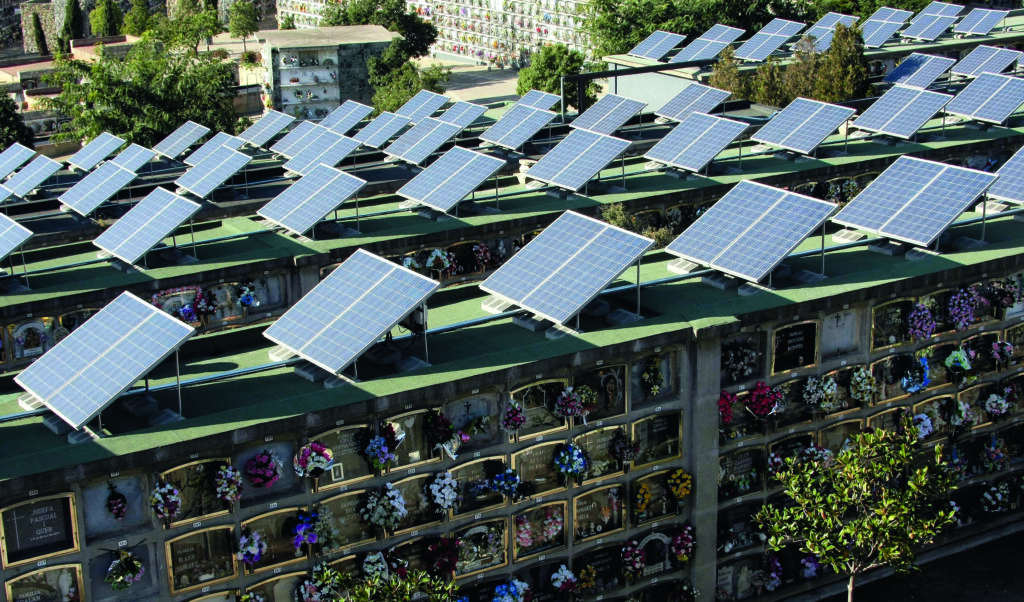

Even though current regulation on self-consumption needs drastic improvement, it is not prohibitive and renewables in Spain still can flourish. Crowd-funded (joint equity ownership) and crowd-financed (cash lending) wind energy projects are developed in Spain to compete without support measures, and in the meantime PV has become so competitive that several newly developed large scale PV plants are being developed to compete in current circumstances in the liberalized marketplace but this market needs serious reforms to accommodate the new emerging energy model.