From the Forest to the Steering Wheel

How leather for European luxury cars is devastating Indigenous lands in Paraguay.

In Paraguay, there are over 13 million cows, double the country’s human population. Half of these cattle are raised in the Chaco region – an area declared a Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations.

To sustain livestock farming, forests are being cleared faster than anywhere else in the world: 279,000 hectares per year, equivalent to over 380 football fields per day.

So far this century, Paraguay has lost a third of its forests, totalling 5.2 million hectares – an area twice the size of Switzerland. In 2020 and 2021, investigations by the NGO Earthsight revealed that European luxury car manufacturers were purchasing Paraguayan leather from Italian tanneries for their vehicle interiors. These tanneries, in turn, sourced leather from Paraguayan companies involved in large-scale illegal deforestation within the Ayoreo Indigenous territory in the Gran Chaco. The revelations sparked significant media outcry. Yet, three years later, little has changed.

Land in dispute

About 200,000 people live in these vast, hot, brownish lands covering nearly 60% of Paraguay’s territory, including 13 Indigenous communities and three Mennonite colonies. In the mid-20th century, the region saw the introduction of cotton farming and more recently, genetically modified soybeans designed to withstand water stress. This resilience has become critical in 2024, with drought conditions leaving reservoirs completely dry or at just 10% capacity.

This region, spanning nearly 250,000 square kilometres – roughly the size of the United Kingdom – is also being eyed for potential oil, gas, and lithium exploration. In its three largest cities, Mennonite cooperatives operate meatpacking companies and leather processing plants, with dozens of trucks transporting hides daily along the Trans-Chaco Highway.

The area is also home to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode, one of the last uncontacted Indigenous populations in Latin America outside the Amazon.

“The only social barriers questioning or challenging the extractive model are Indigenous communities and organisations. There are no significant social movements, unions, or political parties with an environmental agenda,”

Óscar Ayala, a Paraguayan lawyer specialising in human and Indigenous rights and part of the legal team at Tierra Viva.

Ayala represents the Totobiegosode in litigation against the Paraguayan State to protect their land. The Ayoreo people are divided into several groups, with part of the Totobiegosode living in voluntary isolation; meaning that at least one generation has had no contact with mainstream society. The demand to protect their land dates back to the early 1990s, when they petitioned the Paraguayan State to recognise the Ayoreo Totobiegosode Natural and Cultural Heritage (PNCAT). Of the 550,000 hectares requested, only 140,000 have been secured.

Despite precautionary measures issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), illegal occupation of the territory by third parties and constant threats of forest fires persists. “In the face of this, there are no effective protective measures. Today, the IACHR’s resolution is the only guarantee of protection for the Totobiegosode,” Ayala emphasises.

Green hell

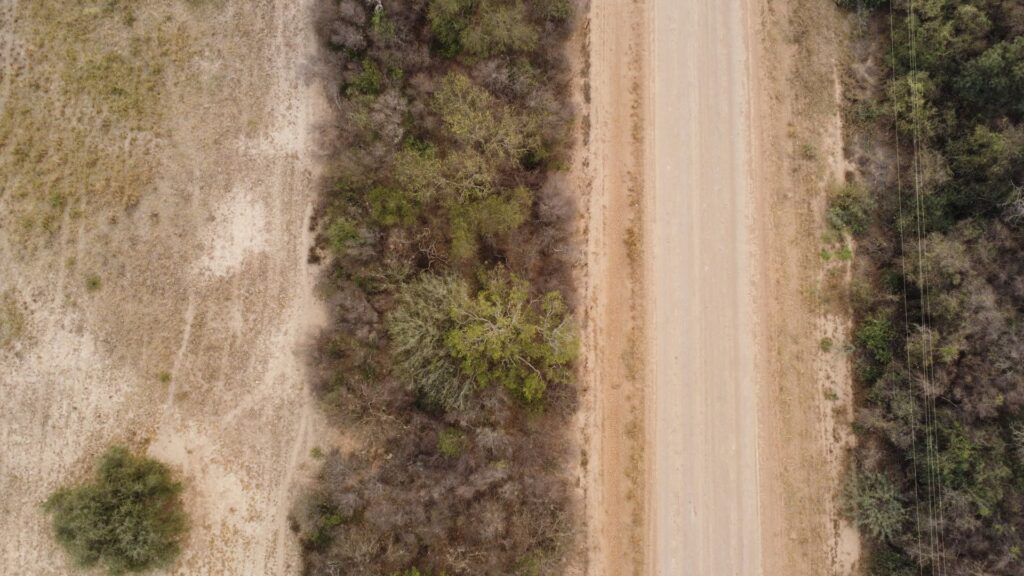

The Chaco, Paraguay’s Western Region, is divided into three departments. As you drive along the highway, the vegetation and landscape grow increasingly arid. Green tones gradually give way to shades of brown and orange, reflecting the region’s dryness. The journey to Filadelfia, the capital of Boquerón, takes about five hours by car. Along the way, steakhouses, large signs promoting cattle ranching, and the constant presence of cows stand out.

The contrast between the wetlands and palm trees at the start and the sense of emptiness that follows is striking. The road is perfectly paved.

Upon arriving in Filadelfia, not only does the landscape change but also the city’s layout: a perfect grid of wide, perpendicular streets. It is known as Paraguayan Germany. Filadelfia, a city of over 20,000 inhabitants, is the departmental capital and base of one of three Mennonite colonies that settled in the Chaco during the early 20th century.

The first colony, Menno, was established in 1927 in the city of Loma Plata, which serves as the administrative centre for the Chortitzer Cooperative – all colonies have associated cooperatives. Here, Canadian Mennonites ventured into what they called the “green hell.” A few years later, in 1930, Mennonites from Russia founded Filadelfia and created the Fernheim Colony. After World War II, in 1947, German Mennonites established Neuland, or “New Land.”

“I found the Promised Land,” reads an inscription in the museum of the Loma Plata colony. According to the colonies’ historical account, the Mennonites arrived in an empty, uninhabited land, claiming ignorance of the existence of more than a dozen Indigenous peoples already living there. The colonists purchased the land from Carlos Casado, a Spanish-Argentine businessman who owned titles to over five million hectares in the Chaco – land acquired after the Triple Alliance War when Paraguay was left economically and territorially devastated.

“In the area where the Canadian Mennonites settled, about 300 Indigenous people live. They are very peaceful and work well. Since the Mennonites arrived, their clothing has improved.”

Statement displayed in the museum, located on the city’s main avenue.

Environmental impact of livestock farming

The expansion of livestock farming in the Chaco has had profound environmental consequences. An investigation by Earthsight found that Chortitzer deforested 500 hectares between 2018 and 2019. The company is headquartered on the outskirts of Loma Plata. The road connecting the city centre to the cooperative’s headquarters is short and well-marked, wide enough for two double-trailer cattle trucks to pass each other without issue.

Upon arriving at the central headquarters, dozens of cows peer passively from trailers, as if they sense their ultimate fate. Inside the large slaughterhouse, known as a frigorífico in Paraguay, where it functions as both a slaughterhouse and a factory, Esteban Arriola, in charge of export documentation for the Chortitzer Cooperative, explains that nearly all production from the approximately 1,000 cows processed daily is exported. “Since Paraguay is a small country, 80% of the meat is exported, 100% of the leather, and 95–98% of the offal.”

Workers in white overalls stained with blood come and go from the building. A group of labourers, conversing in Ayoreo or Nivaclé, crack jokes to lighten the day as they tirelessly load hides into a truck destined for Cencoprod headquarters. Cencoprod, an alliance of the three Mennonite cooperatives (Chortitzer, Fernheim, and Neuland), exports these processed hides worldwide – especially to Italy – under the distinguished label of Wet Blue, a process that turns raw hides into moist leather, still undyed and undried.

Amid this scene, Arriola expresses pride in the material before him: “Given the climate conditions, we have some of the best leather in the world because there are almost no insects or pests to damage it. Approximately 80% is sent to Italy, the most demanding market, mainly for use in automotive factories producing leather for car interiors.”

Arriola adds that most customers using Paraguayan leather are German brands like Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi, and Porsche, as well as Italian companies like Ferrari and Lamborghini. “The rest goes to Brazil, Mexico, and Canada for furniture factories, sofas, and armchairs.” Between Italy, Brazil, Mexico, and Canada, the 100% export rate of hides is complete, sourced from animals raised on deforested land in the Paraguayan Chaco.

Deforestation not only provides space for cattle to grow high-quality hides but also fuels the meat production process.

“The boiler runs on native forest wood, which is still a relatively abundant and affordable resource. We use it to produce heat for all the hot water lines in the factory, but mainly for by-products, cooking all waste to extract oil and produce bone meal,” explains Arriola.

According to Paraguay’s Forestry Law, all rural properties larger than 20 hectares in forested areas must maintain 25% of their natural forest area. In practice, this percentage is often distributed along the edges of the property rather than maintained as a single unit, disrupting the movement of uncontacted people, and hindering biodiversity conservation. The Chaco forest, considered South America’s second most important forest ecosystem, lost four million hectares in the last 15 years. According to the National Forestry Institute, 90% of the country’s deforestation occurred in the Chaco, largely driven by livestock farming.

A class system

Land occupation dynamics in the Chaco have exacerbated a class system in the region, where Indigenous communities and Mennonite colonies occupy very different positions in the social and economic hierarchy.

Evangelina Picanerai, an Ayoreo leader from the Campo Loro community, located two hours from Filadelfia, highlights how Indigenous communities, historically displaced and dispossessed of their lands, remain victims of social and economic exclusion. Along the path to the community’s centre, native forest borders give way to deforested land interspersed with Samu’u or ‘palo borracho’ trees. These trees have bulbous, spiny trunks and lush canopies with cotton-like fruit. Sitting in a wooden shelter that serves as both a school and a cultural centre, Picanerai denounces the risks of genocide facing her relatives in voluntary isolation in the Faro Moro area. “An extermination justified in the name of development.”

“Indigenous people in Paraguay have always been nomads. They stayed in one place for a time and then moved. And we were happy,” says Bianca Orqueda, a young woman in her twenties who is the first singer-songwriter from Nivacchê, a village located just outside of Filadelfia, in the Uj’e Lhavós community. Orqueda speaks about how her community has been relegated to a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Filadelfia, after being displaced from the capital in the 1990s. “They did not want us to be seen. The Mennonites want to keep us well hidden, but they still want us to be their labour force, doing all the work they do not want to do.”

The singer-songwriter refers to what everyone in the Chaco knows: the existence of marked social classes. Mennonite, Latino (Paraguayans who do not belong to an Indigenous community), and Indigenous. At the bottom of the ladder are those displaced by deforestation who work inside the slaughterhouses– the ones who emerge stained with the blood that drains from their lands. “In the more remote territories, where water is a huge problem and food is hard to come by, that’s where the whites take advantage, and the community leaders are forced to sell their sacred trees,” says Orqueda.

The Mennonites are convinced: “We have arrived at the promised land” can be read at the museum entranceon the main avenue in Filadelfia. With a friendly demeanour, they proudly consider themselves Paraguayan – openly stated at the inauguration of their Hotel Florida in the same city. Although they still speak German, they make an effort to speak Spanish, adopting the typical regional accent. Inside the museum, the guide recounts the history of how their ancestors arrived in an “empty territory” and claims that “thanks to their good deeds,” they managed to offer a better life to the communities that lived there: “When you give bread to an Indigenous person, they don’t want to return to the forest,” the guide says with a laugh, quoting a popular saying among their peers.

The cowhides Europe wants

Returning to Asunción along the same highway, a truck filled with hides emits the nauseating stench of fresh blood and entrails reminiscent of the Loma Plata slaughterhouse. The spurts of blood are left behind, but the memory of the cow, which in 30 minutes went from being a living being to a division of boxes and packages, remains impregnated in the brain. On the way to Asunción, near Villa Hayes, the truck from Loma Plata signals to turn into Cencoprod.

When asked about how the Chaco’s development impacts deforestation, they cut off communication.

On the outskirts of Vicenza, in northeastern Italy, lies Arzignano, at the heart of the Chiampo River Valley, a region easily recognisable on the map for its dense concentration of tanneries. Here, leather is in the air. The smell is intense and complex, a mixture of organic and chemical scents that clings to your nose. The acrid aroma is sharp, almost spicy, leaving a rough sensation in your throat. It is the airborne result of processes that combine sulphur, ammonia, and chromium.

For two kilometres, streets are dominated by industrial buildings flanking a steady flow of trucks transporting pale blue hides – the hallmark of the Wet Blue process, leaving leather moist and undyed as it arrives from the tanneries. The hides are carefully packed onto pallets. Outside Conceria Cadore, the hides’ origin and destination intertwine, with blue labels and white lettering revealing their far-off source: Cencoprod, Paraguay. The company has not responded to requests for information about this purchase.

It seems as if all Paraguayan leather ends up here. According to Earthsight’s investigation, two tanneries were the primary recipients of bovine hides from the Chaco: Pasubio and Gruppo Mastrotto. Pasubio, in particular, supplies leather to brands like BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, Porsche, and many others. After the British NGO’s investigation, the Italian company decided to stop purchasing Paraguayan leather.

“We reached an agreement with Survival International in 2023. The Pasubio Group is committed to defending the ancestral territory of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode people and has decided to exclude from its suppliers any leather associated with deforestation in Paraguay’s Northern Chaco Ancestral Territory (PNCAT),” says Francesca Cariglia, Pasubio’s sustainability manager. “We have procedures to verify the origin of the leather. We have sent all our suppliers an Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) evaluation, including traceability requirements.”

As for Gruppo Mastrotto, there has been no response regarding the origin of leather used in its automotive industry. Notably, the group’s founder, Rino Mastrotto, served as Paraguay’s Honorary Consul in Vicenza.

It is nearly impossible to achieve reliable traceability in a country like Paraguay, which has yet to ratify the Escazú Agreement. Without this, Paraguay is not obligated to provide accessible and transparent information on environmental decisions, such as identifying violators of environmental licenses in the Chaco, or to guarantee judicial mechanisms for cases of fumigation or deforestation.

Thus, the Paraguayan Chaco remains a place where nothing can shade the intense heat. The high temperatures help to prevent the cow hides from being attacked by larvae or insects. That is why those who export the skins say that the best leather in the world comes from here. And one of the cheapest.

This report is part of an investigation made possible by the support of the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund and Journalismfund Europe. A project by Revista Late. Mónica Bareiro contributed as a facilitator in Paraguay.