Transparent Energy Peat Production

Have you ever been on a peatland? Untouched peatlands, known also as mires, are wetland ecosystems that are characterized by the accumulation of organic matter. Peat forms when organic matter is produced and deposited at a greater rate than it is decomposed. You may have come in contact with peat when handling growing media for flowers and vegetables, but peat is also used for energy.

EPAGMA

The European Peat and Growing Media Association represents peat and growing media companies and associations at EU level. EPAGMA is committed to the highest environmental practices in peat extraction, to the responsible use of peat as a local energy source, and promoting the importance of growing media for horticultural plant production in Europe.

EPAGMA currently has 17 member companies and 9 associate members based in 14 European countries and has operations in all 28 Member States of the European Union.

Peat has traditionally been used as fuel in some Nordic countries, in Baltic countries and in Ireland. The thermal value and storability of peat has seen it become an industry that presents a domestic alternative to imported oil and coal in Estonia, Sweden, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Finland, while also creating badly needed jobs and development in sparsely populated rural areas. Local fuels mean security and safety when produced near to consumption of heat and power.

In the early 2000s, the producers and users of peat recognized that the world around the peat industry had changed in a way that threatened the business as a whole. Peat production was previously perceived as a threat to pristine mire habitats, and the climate impacts of energy peat became a subject of debate.

This called for clear and transparent guidelines to facilitate the responsible production of peat, a need that was met by the European Peat and Growing Media Association (EPAGMA) that published the Code of Practice for Responsible Peatland Management in 2009, followed in 2014 by the Energy Peat Transparency Policy 2014–2016.

These documents have been highly significant to peat production and its public acceptance, as EPAGMA’s members have committed to applying the principles in their operations. This has also led to the increased availability of information on peatlands, peat production and the use of peat for all parties interested in peat and assessing its use for energy.

Peat Production and Mire Habitats

Peatlands are rare in most European countries. Either there were none in the first place, or they were drained over time to serve the needs of agriculture, forestry and for settlements.

The situation is completely different in the EU countries that use peat for energy production, as they all have substantial peat areas. In Estonia, for example, peatlands account for 22% of the total land area, in Finland for nearly 30%, Ireland 17%, Sweden 16%, Latvia 10%, and Lithuania 10%.

Some peatlands have been drained in these six countries to create arable land or forests. One of the key principles of the Code of Practice for Responsible Peatland Management is that peat must only be produced in drained areas that, usually, have lost their nature value as a mire habitat. This ensures that peat production does not endanger peatlands in their natural state, most of which are also subject to separate conservation efforts.

Peat in the European Union

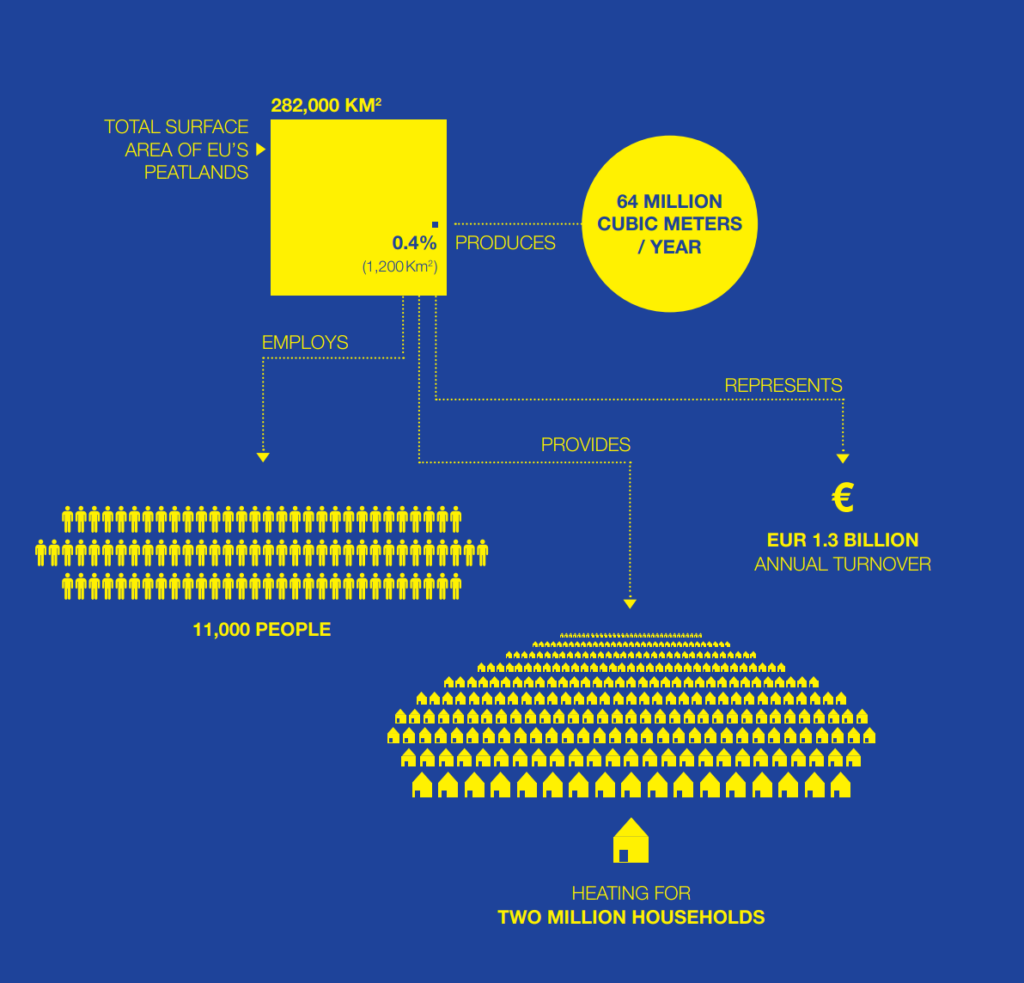

The total annual volume of peat production in the European Union is approximately 64 million cubic meters. The total production area is 1,200 square kilometers, which is 0.4% of the total surface area of EU’s peatlands, 282,000 square kilometers. Peat production employs a total of approximately 11,000 people in various member states and the annual turnover of peat and growing media production is EUR 1.3 billion.

The majority of the peat producers operating in the EU are small and medium-sized enterprises. They have a very significant local employment effect, typically in areas that otherwise have few jobs available.

Peat represents a very large indigenous EU energy source. It contributes to the heating of two million households during cold winters, ensuring the security of supply. Co-firing with biomass, it improves energy efficiency and reduces carbon emissions compared to use of imported fossil fuels. It can also eliminate or reduce the emissions arising from ditched peatlands.

Unaltered peatlands accumulate carbon in the same way as forests, but because the formation of peat takes a long time and carbon is locked permanently under water, peat is not classified as renewable.

Peat is the ideal growing medium

Energy production is just one way of taking advantage of the special characteristics of peat. The most widespread use of peat internationally is as a growing medium constituent. For instance, peat can also be used for soil improvement, and as litter used in animal husbandry.

Today, peat remains the main constituent for most growing media mixes as no other material offers the same combination of many favorable characteristics. It is favored due to its high water holding capacity and good aeration. As the pH and nutrient content of peat are low, almost any kind of growing medium can be produced with the addition of liming material and fertilizers.

Smart Peat Production Benefits the Climate

Allocating production to previously ditched peatlands is a good solution from the climate change perspective. Peat in ditched peatlands gradually oxidizes, releasing greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. When used for energy, the same carbon dioxide is released in boilers when peat is extracted from those drained areas. Peat is used for electricity and/or heat production instead of simply escaping into the air. Moreover, if peat is used in a combined heat and power (CHP) plant and co-fueled with wood fuels, then the use of wood fuels becomes more efficient. This is because of the different properties of the fuels.

The land area underneath peatland is available for other uses after peat is extracted. Those areas are typically reforested, used for agriculture or rewetted. New vegetation absorbs carbon dioxide and a carbon sink is formed again on the former peatland site. Life-cycle assessments indicate that peat produced under these principles may be superior to coal from the climate perspective: the carbon dioxide emissions, based on measurements taken at the top of the boiler chimney, are similar, but when you account for peat production areas turning into carbon sinks, the peat’s CO2 emissions lifecycle can be lower than coal’s.

Studies on the subject include the PhD thesis of Dr. Sanni Väisänen, Lappeenranta University of Technology in Finland. According to comparison of the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of different energy sources, the climate impact of energy peat extracted from previously dried eutrophic peatland rich in nutrients is 72.7 g CO2-eq/MJ based on a life-cycle analysis (LCA), which contrasts with the combustion emission figure of 107.5. For reference, the LCA value for coal is 111 g CO2-eq/MJ. Swedish studies show even lower results for peat taken from forestry drained peatlands.

After-use of Peatlands

Transitioning of peat extraction sites after peat production to new uses is another key area of the Code of Practice for Responsible Peatland Management. This is important from the climate perspective and represents broader responsibility in the peat industry in the form of a commitment to not leaving behind scarred and unattractive landscapes.

Traditions for peatland use and ecological conditions vary between countries. After-use may include rehabilitation of the peatland ecosystem, alteration of land use to forestry, agriculture, recreation or urban development, or a combination of different land use forms. National legislation, land owners, and environmental policy guidelines set the outlines for possible after-use regimes in many countries.

As many peat extraction sites are located in low-lying areas, they begin to accumulate water naturally after peat production ends. This creates the opportunity for paludification and the creation of wetlands and lakes. This is done in Finland, Sweden and Ireland, where they often become very popular with bird species that require wetland habitats. Former peat extraction sites are often also located in remote areas, which makes them well-suited for wind and solar power generation, as shown in Ireland.

Information Widely Available to the Public

Operating in accordance with the Code of Practice for Responsible Peatland Management takes into consideration the environment and the EU countries’ goal to increase their energy self-sufficiency. Peat producers offer practically everyone the opportunity to verify that they genuinely operate according to these principles. Their commitments under the EPAGMA Energy Peat Transparency Policy 2014–2016 include the following:

- Providing essential peat extraction information concerning production and environmental impacts for citizens by the end of 2016.

- Displaying the environmental licenses of production sites and the environmental figures required by these licenses by the end of 2016.

- Providing appropriate channels and opportunities for interacting with citizens as well as local and European authorities through events, websites and site visits.

Countries’ Stance on the Role of Peatlands

Peat is a CHP cornerstone in Finland

The Finnish energy system is characterized by CHP using wood and peat as fuel. Peat plays an essential role in the big picture, as it ensures the continuity of power plant operations during the coldest times of the year, and if wood fuels are unavailable. Peat differs from wood fuels in the sense that it can be stored for extended periods of time without a significant reduction in its energy value.

There are 60 CHP power plants in Finland. In addition, there are some 120 heating plants that use peat (and wood) as fuel, and hundreds of smaller peat-fueled heating centers located at farms, greenhouses, amongst others. The homes, schools and workplaces of approximately one million Finns are heated entirely or partially by peat. The production and use of peat directly and indirectly employs more than 10,000 people in Finland.

Finland emphasizes the use of biomass and the impact of advanced biofuels on the improvement of energy security as native sources of energy, cost efficiency and competitiveness in energy efficiency as well as the significance of peat as domestic fuel that can be utilized regionally.

Peat improves energy security in Lithuania

Lithuania’s position among European countries is exceptional with regard to its energy supply. It is an energy island with very limited access to European gas and electricity networks. With this in mind, Lithuania sees peat as part of the solution for improving its energy security. In 2015, the Lithuanian Government approved “the National Heat Sector Development Programme 2015–2021”, providing opportunities for wider usage (5–11% of the total energy balance) of energy peat in the Lithuanian heating sector.

The peat industry already employs more than 1,300 people in Lithuania and is an integral part of the country’s heating palette. With Lithuania’s peat reserves suitable for production estimated at 248 TWh, there is potential for much wider use. Taking advantage of these reserves would create the opportunity to supply 1.8 million households with heating and reduce natural gas imports correspondingly.

An important local fuel in Estonia

Peat has been included as a fuel source in the Estonian National Development Plan for the Energy Sector until 2030. One of the main goals of the plan is to produce most of the country’s heating energy from renewables and peat. Considering peat’s significant energy potential, local origin, availability and low cost, the possibilities for using peat-fueled facilities should be increased to the same level as other fuels.

In line with these plans, the use of peat in energy production has increased in recent years in Estonia. The country currently has two peat-fueled combined heat and power plants (CHP) and 21 district heating plants.

Peat also has regional significance, particularly in heating production, and in electricity production. Some 82,000 Estonians use heating produced by peat, and production operations provide jobs for more than 300 people. While these may not sound like large figures, the local impact is significant in such a small country.

Latvia sees major potential in peat

One of the goals outlined in the Latvian Energy Strategy 2030 is “to promote use of local energy resources, including peat extraction.” This view is also supported by the Latvian Energy Guidelines 2014–2020, which state “There is potential for peat extraction. Energy peat extraction at peatlands that are already prepared for extraction, with an existing license, can be started in areas totaling around 4,000 hectares.” The Guidelines further indicate that there is a need to “evaluate the opportunities of effective use of peat and acquisition-related conditions.”

Latvia’s use of peat for energy is the lowest among Europe’s peat-producing countries. Peat is mostly used by individual households. However, as the Latvian Energy Strategy states, peat is seen as having major potential. This is understandable since imports account for 70% of Latvia’s energy consumption. Latvia is highly dependent on natural gas and has a shortage of energy. The energy value of Latvia’s peat reserves suitable for production is estimated at 663 terawatt hours (TWh). Increasing production to 700,000 tons would enable the generation of 2.1TWh of energy per year.

Peat complements wood fuel in Sweden

In its 2009 Energy Bill, the Swedish Government stated that peat is an indigenous energy source of significant importance for energy security. It also stated that peat has a role to play in a sustainable energy system as complementary to wood fuel.

This remains accurate to this day. Sweden primarily uses peat in combination with wood fuels at more than 20 heat and power plants. The combination of peat and wood fuel leads to more efficient combustion and a cleaner furnace, thereby reducing maintenance costs. Co-fuelling also broadens the fuel mix, contributing to greater security of supply.

More than 140,000 Swedes use heating generated from peat. The peat industry employs some 600 people in Sweden. Peat production and use is a particularly significant source of employment in sparsely populated areas.

Ireland’s most important domestic fuel

Ireland primarily uses peat for electricity generation, which makes it different from the other peat-producing countries where the emphasis is on heating. There are three major peat-fuelled condensing power plants in Ireland, producing over 6% of the country’s energy demand. Peat is also traditionally used for heating individual buildings. In total, approximately one million people in Ireland use peat to heat their homes.

Next to wind, peat is currently Ireland’s most significant domestic energy source. Its importance is stressed by the fact that 89% of Ireland’s energy is produced from imported fuels. The energy peat industry employs 1,500 people. Privately harvested energy peat provides an estimated 8,000 – 9,000 additional jobs.

The importance of peat is also recognized at national level. The Irish National Peatland Strategy published in 2014 states that peat production for energy remains important for local and national economies. However, peat production will decrease in Ireland by 2030, as the peat extraction sites controlled by Bord na Móna will be used up. Areas released from peat production are nevertheless used for continued energy production: wind energy generation has already begun and both solar and energy crop possibilities are being developed.