Genk’s Transformation Honors Its Heritage

The EU Green Deal’s vision for carbon-neutrality by 2050 requires drastic changes to the way we live, move, and produce energy to attain a competitive economy “decoupled from resource use.” Getting there entails a total shift in approach, mind-set and culture, as demonstrated by Genk – one of Belgium’s previous coal mining hubs. This is how Genk is using its sooty past to its advantage in forging a clean, diversified economy.

Over the last 100 years, coal mining was the main industry in Genk, shaping its image and culture. When the city was forced to permanently cease mining activities, local leaders looked for an alternative approach to generate revenues and create opportunities. Ongoing to this day, the transition away from industrial activities in Genk has been a long process with multiple phases.

The first major transition happened in the 1960s, after the first coal mine closure in Genk. A newly established Ford Motor Company plant was established soon after, recovering many of the coal mining jobs that were lost. During the 1980s, the city started to attract more industrial companies largely related to car manufacturing and logistics companies, becoming the core of Genk’s economy.

Economic diversification

In 2014, the car manufacturer shut down its Genk facility, forcing the city to transform yet again. This time around, however, officials decided to steer away from an industrial model dependent on a single company or industry and instead work towards industry diversification. Located in a peri-urban region, Genk is the largest city with only around 66,000 inhabitants. Large companies tend to prioritize more robust and larger urban centers, so attracting them to Genk was a bit of a challenge. The city’s current transition approach however focuses on developing an economy based on a mix of technology firms, clean energy companies, and an array of options for the service industry. Moving away from a mono-industrial approach and towards economic diversification was key for the success of the entire region of Limburg.

As a result, Genk has become a dynamic entrepreneurial city devoting attention to sustainable jobs and welfare creation. To secure and to strengthen the future economic competitiveness in this phase of transition, Genk is using its manufacturing industry to its advantage for an innovative, manufacturing and knowledge economy.

Heritage as a driver

“Limburg is no longer a coal region from a mining perspective, but it is still a coal region culturally,” states Peter Boutsen, a consultant in redevelopment of coal mines and mining regions and part of the Regional Platform Mining Area (a close cooperation initiative of the Mayors of the region) during 1990-2000 that played a major content developing role in Limburg’s transition.

Genk’s economic diversification fo- cused on moving away from the past and looking into the future; however, the key to success was embracing its past. Boutsen continues:

“One of the key factors for success was that we finally managed to embrace our own heritage and culture as a driving force to communicate with everybody and build a new image for the region. It also helped us to see our heritage as an asset and take advantage of what was available to us. You have to start with what you have today. And what we had was a rich cultural heritage, infrastructure, and skilled people who want to and can work.”

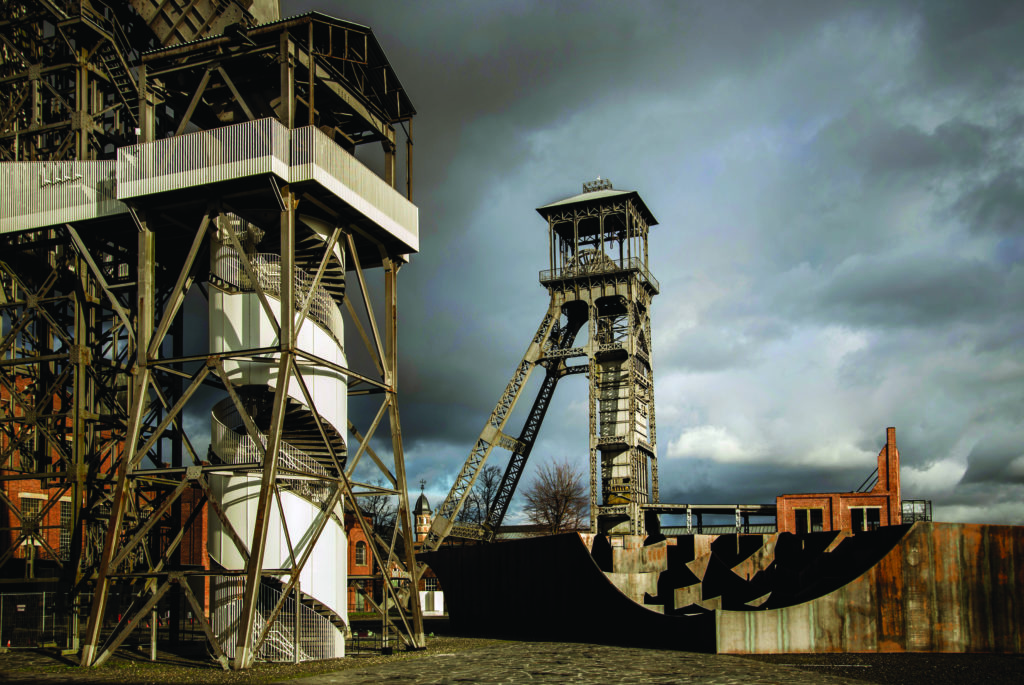

Various levels of local authorities had different thoughts on how the transformation could be implemented and agreeing on a common plan for regional redevelopment was difficult. One of the greatest challenges was to save the former mining facilities from being demolished. It was key to get decision-makers to see the old coal mining infrastructure as an asset that could bring them forward, rather than as an obstacle that needed eliminating.

The sites, such as the Waterschei coal mine, had been left abandoned and in decay for many years since it closed in 1987. Despite only entering the discussion decades after the mines closed, the protection of coal mining heritage and infrastructure became one of the main guiding principles of this transition phase, taking advantage of opportunities that currently existed in the local area.

“Representatives of cities and regions we talk to agree that we face a historical turning point, and they are ready to shape the transformative process in partnership with all relevant actors,” states Carsten Rothballer, Coordinator, Sustainable Resources, Climate and Resilience at ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability. “It is a once in a lifetime opportunity for elected leaders to access and mobilize substantial funding for an inclusive and affordable sustainable energy supply.”

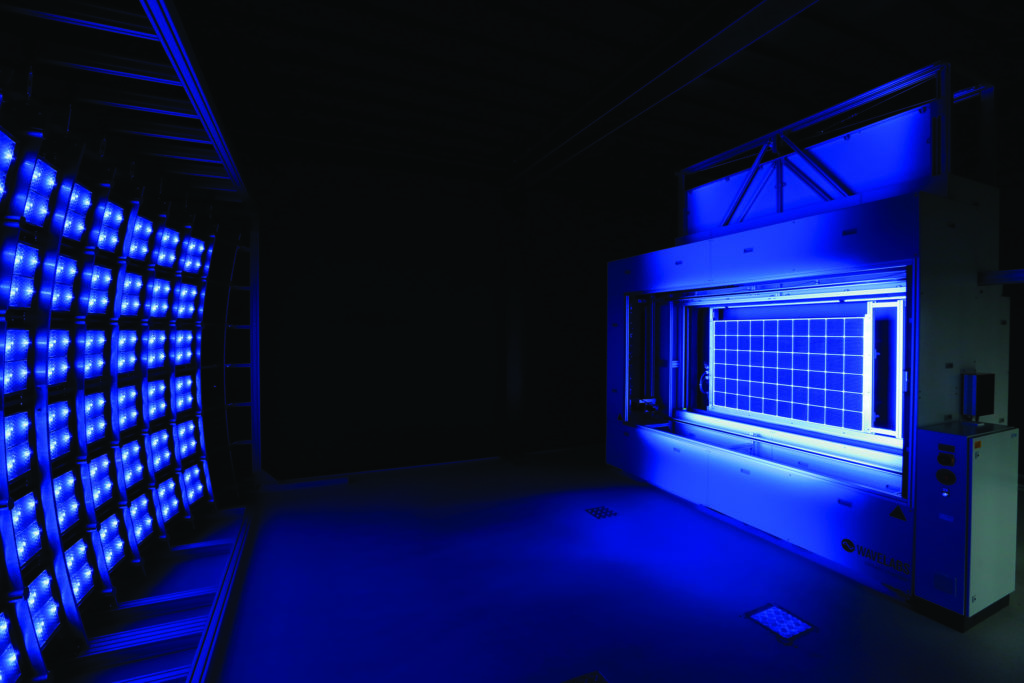

The transformative process mentioned by Mr. Rothballer can be seen in Genk through various projects that focus on heritage and the re-use of the mining sites. Three projects, all related to the conversion of decommissioned coal mines, have been of particular focus in Genk. One of the revived places is Thor Park, situated in the former Waterschei coal mine, which is now a symbol of transition from coal mining to green energy. This former mine once employing 7,000 people, it is now a 93-hectare technology park and a hotspot for technology, clean energy and innovation, hosting companies in the fields of research and development, innovation, business, talent development and urbanization.

Another impressive example is the Zwartberg mine. It has been converted into a business park that hosts primarily SMEs and local entrepreneurs, and houses a public garden, an art studio and a research park on biodiversity, known as La Biomista.

The C-Mine, in the former Winterslag coal mine, functions as a creative hub and cultural center, where the focus is on education, creative economy, recreation, and art. It includes a cinema, a theatre, and a faculty of the Luna School of Arts, as well as space for events, and it is considered an incubator center for start-ups. It also attracts tourists with its unique virtual tour of the former mining site.

Today, Genk has successfully shifted from a mining to manufacturing and knowledge economy and is – together with the surrounding region – an example of redevelopment of industrial and mining infrastructure. Instead of demolishing the already existing mining facilities, the examples above demonstrate how to create a unique landmark that respects heritage as an important part of regional history, transforming heritage spaces into modern workplaces.

It has to be acknowledged that, despite the progress made, the region still faces re-employment challenges for those whose skillsets have been made obsolete due to the closure of the automotive industry and the coal phase-out.

European coal regions are working together

Limburg is an active participant in the European Commission’s Platform for Coal Regions in Transition that was launched in 2017 to assist these regions in changing times. The Deputy Director of the Directorate-General for Energy of the European Commission, Klaus-Dieter Borchardt, highlighted that “the regions need to adapt to a new era,” adding that the Platform was established “to help regions on the ground to undertake the transformation with concrete projects.” The Platform offers regions a space to build relationships and foster cooperation, to develop support materials and case studies, and to get technical assistance on strategy development and project identification.

Paul Boutsen, who presented Limburg’s success story to a broad range of stakeholders during one of the Platform’s working group meetings in Brussels, reflected: “I met people from Silesia (Poland); we have put projects on the table and we will soon start working together on a project to create syngas and hydrogen out of the energetic fraction of municipal waste.” He praised the Platform’s role in creating this momentum and facilitating exchange, adding, “People’s enthusiasm to share their knowledge is growing and regions will soon start writing and developing projects together.”