Hydrogen Valleys Energizing Mobility

Renewable energy hubs offer environmental and economic promise, but significant barriers remain.

Transportation is one of the major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, primarily due to its reliance on fossil fuels. In an attempt to cut emissions, governments are shifting their focus to alternative sources such as hydrogen, which offers a potentially cleaner alternative. However, issues with storage and transportation have slowed the rollout of hydrogen-powered transport, as often it is not a logistically or economically viable option.

A new focus towards so-called ‘hydrogen valleys’ offers a potential solution, bringing hydrogen providers and users closer together, reducing transport costs and storage needs, and boosting the chance of more hydrogen-powered transport in communities around the world.

What is a hydrogen valley?

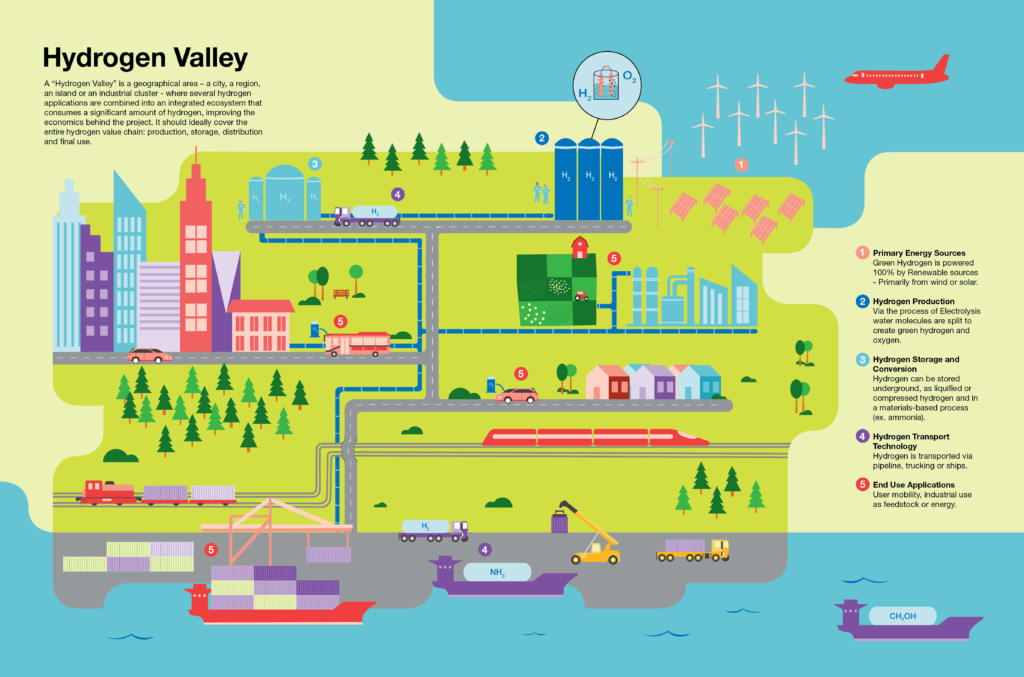

Hydrogen valleys are geographical regions that create a hub for the production, distribution, and use of hydrogen, offering more than one end sector or application in different areas of mobility, industry, and energy. The name is a reference to Silicon Valley, with the idea of creating a localized economy that is fueled by hydrogen, reducing the need for long-distance transportation, something that has been one of the key barriers to the uptake of hydrogen as an everyday renewable energy solution.

As explained in the 5 Dimensions of Hydrogen Valleys video and still map below:

These hydrogen valleys can also act as technology hubs, with companies developing new technologies close to those that will be utilizing them and being positioned close to hydrogen production sites. Bringing together a ‘critical mass’ of expertise and resources encourages collaboration and innovation, creating an ‘ecosystem’ in which technologies can be developed with hydrogen in the center.

This again reduces the total cost of further research, making progress more effective and potentially maximizing returns on investment in the infrastructure required to set up each valley.

European investments leading the way

In 2021, the EU set up the Clean Hydrogen Partnership as a replacement for the former Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (FCH-JU). This new organization focuses on research and innovation opportunities that facilitate the uptake of hydrogen use and meeting EU Green Deal targets.

The Clean Hydrogen Partnership has received €1 billion from government funds, with a further €1 billion from private investment, focusing on the rollout of ‘sustainable hydrogen’.

In 2019, the EU also set up the H2 Valleys S3 Partnership to develop fuel cell and hydrogen (FCH) applications and value chains, as well as to contribute to the ‘greening’ of the production of hydrogen from renewable energy sources. The partnership now has 60 regions contributing, making it the largest hydrogen-related partnership in Europe.

Initial deployment steps

The Northern Netherlands was the first region in Europe to receive EU funding for its hydrogen valley, with sustainable mobility as a central part of the plan in the area. The HEAVENN project has received €90 million and has clean mobility solutions at the core of its plan, listing targets of 105 hydrogen-run public transport vehicles, 20 trucks, and 5 filling stations, along with the creation of an entire hydrogen value chain. This means connecting businesses, producers, and consumers in a small area, keeping transport distances low and reducing costs.

What makes this project a truly sustainable solution is that it prioritizes green hydrogen across all areas of the localized hydrogen economy it is creating. Given the abundance of both off-shore and on-shore wind resources as well as solar power, it aims to use hydrogen as a storage method and as an ‘energy vector’ for decarbonization beyond electricity production, in particular in industry, heating, and transportation.

The rollout of hydrogen valleys is ongoing across the world. According to the Mission Innovation Hydrogen Valley Platform, there are 83 hydrogen valleys registered, with €115 billion invested in the projects.

No one-size-fits-all

Exploring the different hydrogen valleys in development, it is quickly apparent that these are all vastly different projects, attempting to harness the local environment and cater to the needs of the local population.

Take the BigHit project, for example: an ambitious plan to turn the Orkney Islands in the far north of Scotland into a hydrogen valley. With immense potential for wind and tidal energy to produce hydrogen, the fuel could then be used for boats supplying the islands. These hydrogen-powered boats would have access to hydrogen refuelling stations in the same place as hydrogen-powered trucks, creating a hydrogen ecosystem for transportation and production.

However, hydrogen valleys are challenging. A €16 million project in Western Australia was scrapped in July 2023 as developers better understood the economic potential of having their energy park in closer proximity to users, especially heavy industries. Another project, Green Hydrogen @ Blue Danube, that was focused on transporting hydrogen from Romania to Austria across the Danube River, was also discontinued in 2023.

This shows the scope of the potentialities and challenges of hydrogen valleys. In some cases, it is unavoidable that hydrogen must be transported long distances; in others, having the production as close to end-users as possible is the way to go. Both are about creating inter-connected hydrogen economies.

Changing identities

Other regions in Europe are now seeking to become hydrogen valleys. This is particularly the case in those that previously relied on fossil-fuels.

LEAG, one of Germany’s biggest energy companies whose tagline from a quick Google search reads ‘energy from lignite’, are promising a transformation away from brown coal in Lusatia, an area close to the Germany-Poland border. They aim to replace the 8GW of electricity produced from coal with up to 14 GW produced entirely from renewables, with 3GW from green hydrogen.

In Poland, PKN Orlen is actively pursuing its hydrogen strategy towards producing and supplying zero- and low-carbon hydrogen as an alternative transport fuel. The company’s “Hydrogen Eagle” project, recently approved by the European Commission, signifies a critical step in this direction, with the construction of hydrogen refueling stations across Poland. Linking Gdansk and Gdynia, the Amber Valley project, also led by PKN Orlen, has the goal to catalyze the development of a sustainable hydrogen economy in Poland’s Pomerania Region. This comprehensive effort involves the establishment of a complete hydrogen value chain, encompassing hydrogen production, storage, and distribution, ultimately serving diverse applications such as mobility, industry, and energy.

In Czechia, it was reported in July 2023 that three coal mining regions want to become hydrogen leaders in Central Europe, specifically as hydrogen valleys, creating a new identity for regions previously defined as coal hubs.

This is not just the case in Europe. In April 2023, Gujarat, India announced plans for a hydrogen valley innovation cluster with the goal of developing clean hydrogen valleys by 2030. India has stated that it aims to cut emissions in the developing country by 45% by 2030 and is turning to hydrogen valleys as a means of achieving its targets.

Meanwhile in Michigan, USA, General Motors, one of the Big Car faces of mobility in North America has announced it is working with Norwegian green hydrogen company Nel to create a giant new green hydrogen production facility. It may not be branded as a hydrogen valley, but it is again tapping into a wider hydrogen economy.

Not all hydrogen valleys are green

While it may seem obvious for sustainable energy alternatives to focus on green hydrogen, not all hydrogen valleys are focusing on renewables – nor are they necessarily that sustainable. For example, the Kawasaki Hydrogen Road has a broader definition of what producing sustainable energy looks like.

The project is looking to tap into hydrogen resources abroad, which then creates an interlinked hydrogen value chain. One objective is to produce ships that can transport liquid hydrogen. As the first producers of ships that carry liquid natural gas (LNG), there is hope that this could bring together hydrogen-producing sites with consumers, creating distant, but connected, hydrogen value chains.

However, the Kawasaki Hydrogen Road is based on hydrogen fueled by brown coal (or lignite) in Australia, a fossil fuel that often goes unused. This is being branded as a cleaner way to produce hydrogen, and while this offers a short-term solution and some emission savings, it does not go far enough to be called sustainable energy production. It is also facing heavy resistance from local politicians questioning the sustainable merits of the project.

Misleading sustainability claims

One of the highest-funded projects on the H2Valleys list is the Edmonton Region Hydrogen Hub, promising a future “where buses, trains, heavy trucks, home heating, and farm equipment all run on zero-emissions hydrogen fuel, an essential component of the new clean energy system”.

When justifying the question ‘why hydrogen?’, they explain the importance of green hydrogen in the energy transition, but also blue hydrogen. That is produced by using natural gas – a fossil fuel. Energy companies are quick to argue that blue hydrogen is environmentally friendly, with one company suggesting that it has “zero CO2 emissions”.

Many environmentalists are skeptical of blue hydrogen. The techniques to produce blue hydrogen can differ, with some actually producing more emissions than creating electricity with natural gas, while other methods can offer just a 13% reduction.

It is a ‘net positive’ if emissions are reduced, but should hydrogen produced with these methods still be labelled ‘clean hydrogen’?

The Black Horse Project, supported in Slovakia, Hungary, Czechia and Poland, is aiming to put ‘10,000 emission-free hydrogen trucks’ on the road in Central Europe. Yet digging through published plans behind the project, there are still mentions of using grey hydrogen – at least in the short term.

Likewise, the HyNet Project based in northern England describes its fuel only as ‘low carbon’, offering branded techniques behind the fuel but without giving consumers a clear indication of the environmental impact of their hydrogen.

The future is hydrogen

Despite the questions surrounding the environmental impact of hydrogen and its methods of production, more companies are turning to it as the fuel of the future.

In June 2023, the first hydrogen train in North America took to the rails; meanwhile, the flagship EU hydrogen truck project kicked off in Brussels in March 2023. Even companies like EasyJet are looking to hydrogen to maintain the feasibility of short-haul air travel and cut down flight emissions.

The possibility of emission-free transport in urban areas and over long-haul routes is enticing, but the redevelopment of regions negatively affected by mining or the economic struggles as the industry shrinks would be an even greater achievement.

Hydrogen valleys offer a pathway towards these sustainable and decarbonized transport systems. By integrating local renewable energy sources with hydrogen production, storage, and distribution, these valleys pave the way for a cleaner, greener future.

As technologies evolve and economies of scale kick in, the cost of hydrogen infrastructure is likely to decrease, making hydrogen valleys even more attractive. Creating these interconnected hubs facilitating the hydrogen economy is not yet a perfect plan but does point to a cleaner and more profitable future for heavy industry and transportation.