Could Social Housing Be the First to Decarbonize?

Deep renovation of Europe’s building stock is necessary to reach ambitious climate change targets. But the reality is that “business models and solutions are not entirely there yet, in terms of cost and quality,” says Sébastien Garnier, innovation and project manager at Housing Europe, a representative network of social and public housing organizations. Housing Europe, along with 15 other partners gathered together in the Horizon 2020-funded HEART project consortium, is aiming to develop a new holistic approach to deep renovation using cloud-based decision support systems. Sounds hi-tech, but Garnier says: “in the end, it’s all about the people.”

According to European Commission estimates, almost 75% of Europe’s building stock is currently energy inefficient, and the renovation rate ranges from just 0.4 to 1.2%, depending on the country. Yet minimizing energy consumption on buildings – and indeed, developing nearly-zero energy buildings (nZEBs) and positive-energy (or ‘smart’) buildings that can interact with the grid – is central to Europe’s climate and energy policy, and essential for meeting ambitious targets for 2030 and beyond.

Housing Europe, a network of social housing organizations whose members manage about 11% of households in Europe, is one of 16 partners in the Holistic Energy and Architectural Retrofit Toolkit (HEART) project aimed at developing a multi-functional retrofit toolkit that can transform buildings into smart, low-energy homes and offices. “Although HEART’s holistic approach relies on energy systems automation, algorithms and smart appliances, it is all about the people,” says Sébastien Garnier, innovation and project manager at Housing Europe in an interview with REVOLVE.

“In general, what you see in the social housing sector – and also for middle income household renovations – is that the business models and solutions [for deep renovation to nearly-zero energy building level] are not there yet in terms of cost and quality, if we want to reach the ambitious energy efficiency goals in the residential buildings sector. So, this explains why in many cases no action is taken or substandard solutions are chosen,” explains Garnier. This is especially a critical issue in the social housing sector, which struggles with tight budgets and limited finance.

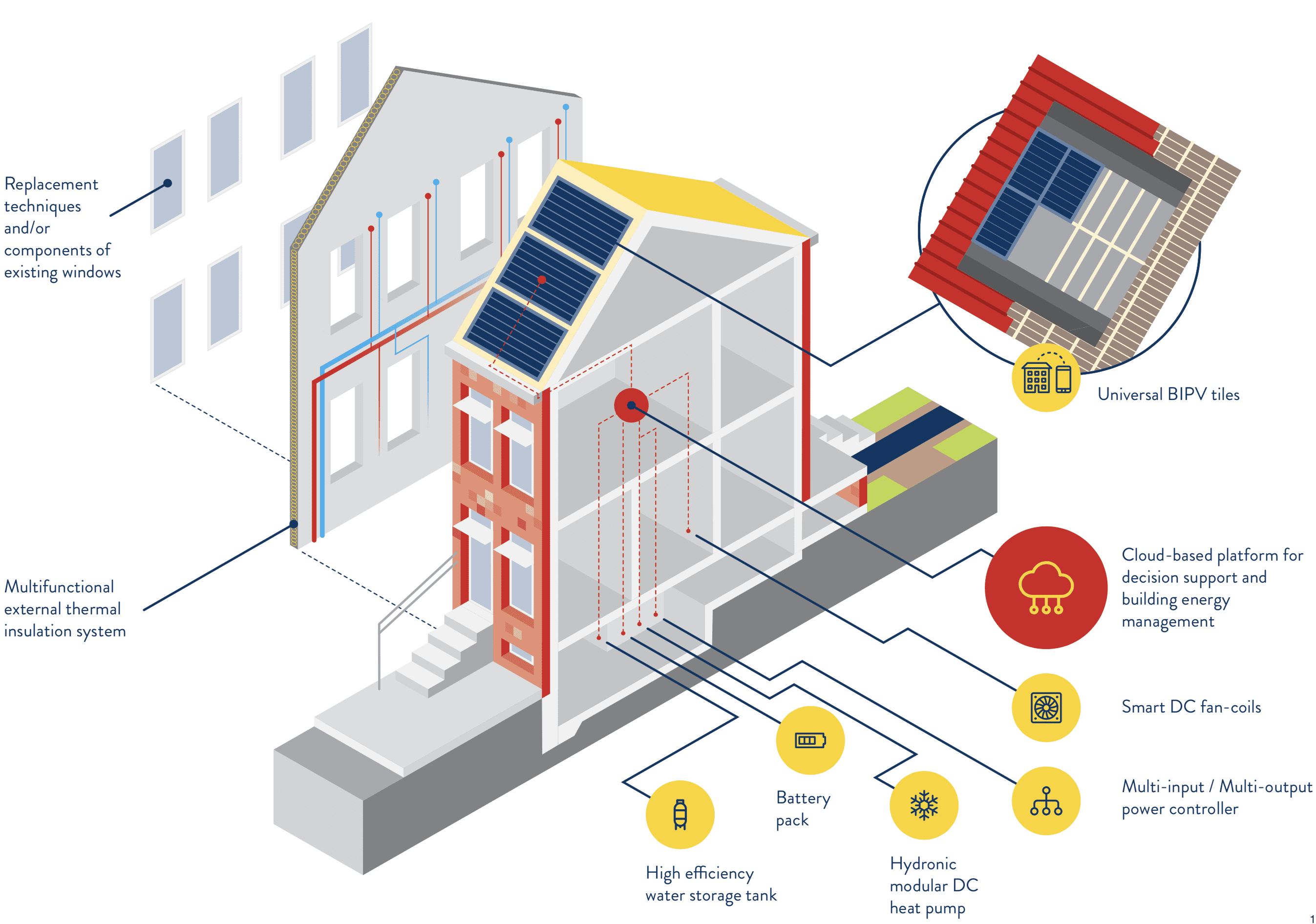

“There is a huge need to continue to work on innovations in this field if we want to achieve the objectives.” To address this, a key innovation of HEART is a cloud-based decision support system that can improve the business case by identifying the optimum combination of low-carbon technologies and operating strategies for a building. “This is a holistic package, that combines all the different elements – photovoltaics, renewables, insulation – for deep renovation, and that can help to choose the most optimal mix and settings. This means that HEART is an excellent example and test case of ways to get the best value, in terms of energy performance and investment costs,” says Garnier.

But HEART’s functionality goes beyond the design stage. The cloud-based platform uses advanced building energy monitoring systems to optimize energy use when the building is occupied post-renovation. “This is a valuable aspect, that will improve the decision-making process for building owners and managers using the HEART system,” notes Garnier. “Also, imagine the potential learning effects if HEART-based cloud systems would connect thousands of these buildings in the future.”

HEART combines photovoltaics, renewables and insulation for deep renovation

Transforming social housing into low energy buildings

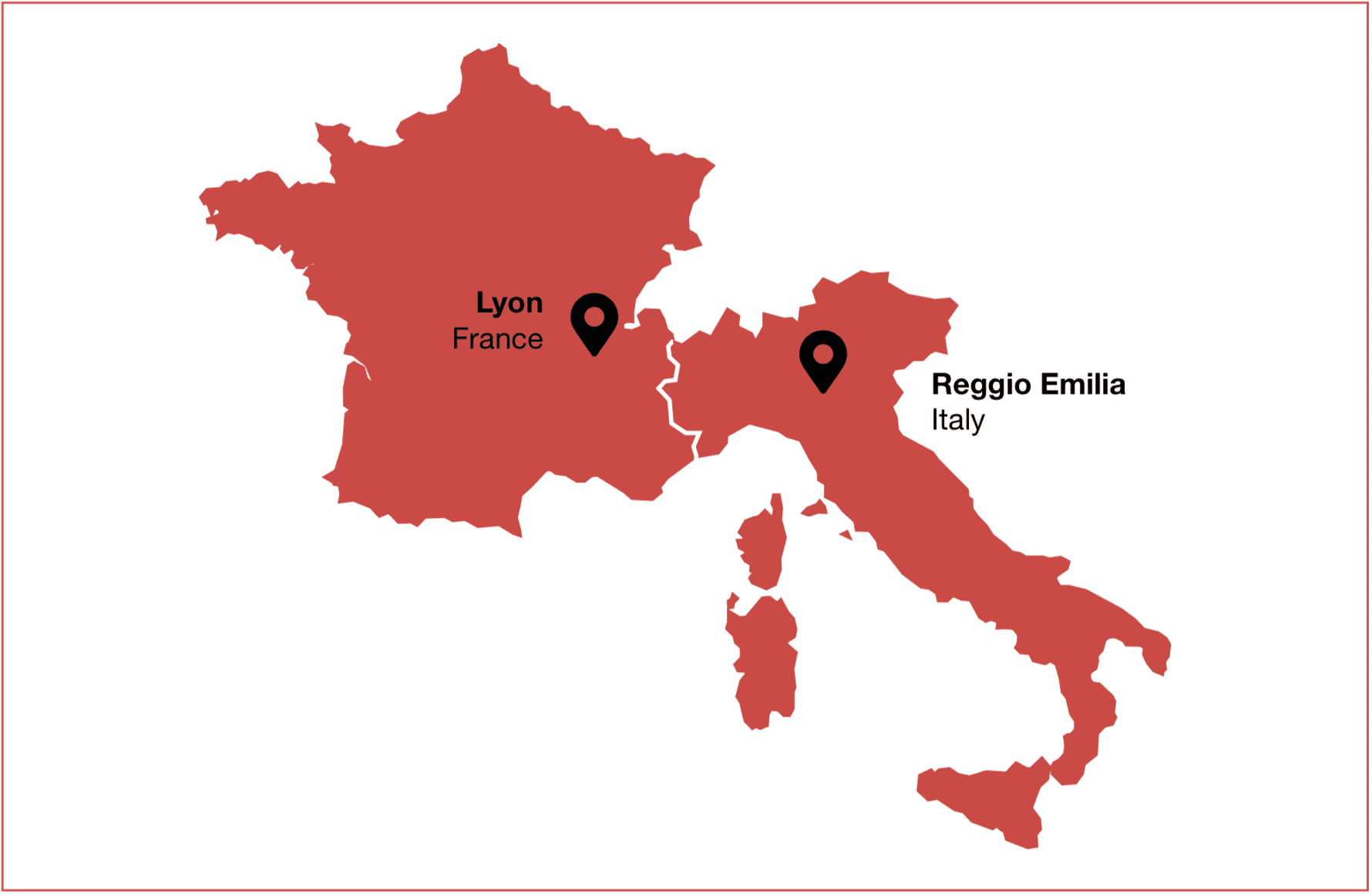

The HEART system will be tested out on four buildings, both of which are managed by social housing providers. One of these buildings is managed by Est Métropole Habitat, a social housing organization managing 16,000 social housing units in eastern Lyon, France.

Another building is owned by ACER (Azienda Casa Emilia-Romagna) Reggio Emilia, a public housing provider in Reggio Emilia, Italy. After the HEART interventions, the buildings will be in line with nZEB levels of energy consumption (<50 kWh/m2/yr) – and should achieve energy savings of 90%.

These test cases for the HEART system are typical of the target market in Central and Southern Europe: medium-size, multi-story condominium buildings, constructed in the second half of the 20th century and located in moderate climatic zones. It is estimated that there are around 1,005,000 such buildings in Europe.

In terms of the market potential of HEART, much depends on the market segment in question. Garnier is quick to distinguish between different groups with different needs: homeowners of single-family dwellings, homeowners in apartment blocks (gathered in homeowners associations), tenants in dwellings from private landlords, and finally tenants in dwellings managed by professional social, public, cooperative or private housing providers.

“These first three groups need much more intensive support in terms of skills and finance to undertake deep renova-tion,” says Garnier. “Here we can see that one-stop-shop service offerings are emerging, and that this is often driven by local authorities.” This is as much about social innovation – “basically, organizing and motivating people,” says Garnier – as the technical aspects, andincorporating new types of tailor-madefinancial packages will be key to get the market moving.

In the social and public housing market, the decision to renovate is usually taken by the owner or landlord, “so here you are dealing with professionals who are used to renovation projects like this” Garnier says. “Yet further financial innovation needed for this sector too, as regulation that prevent local authorities from going into debt also prevents them from investing in better buildings. “We need to consider how to tackle the debt issue – one possible option that could be tested is via an ESCO (energy service company) model, where by the ESCO takes on the debt,” says Garnier. Although, this is only a second-bestoption. It would make more senseto allow public investments for such societal and environmental long-term investments. Especially in those cases where it is clear there is a business case with a financial pay-back (i.e. energy bill savings and health benefits).

European success story

Energiesprong – an innovative approach to renovating social and public housing to nZEB level – has proven to be remarkably successful. Originating in 2013 inthe Netherlands as a government-funded innovation program, Energiesprong brokered the “Stroomversnelling” deal between Dutch building contractors and housing associations to refurbish 111,000 homes to nZEB level.

Two years later, Stroomversnelling evolved into a market initiative designed to take NZE (Nearly Zero Energy) to the next level. Currently, Energiesprong teams are active in France, the UK, Germany and New York State.

75% of Europe’s building stock is energy inefficient with renovation rates ranging from 0.4 to 1.2%, depending on the country.

Source: European Commission

Garnier is familiar with the Energiesprong initiative through his work at Aedes, the Dutch federation of social housing providers. “Energiesprong became successful, in part because they were able to make deals involving bigger volumes. Social housing providers demonstrated the potential in terms of scale under the right conditions of costs and performance. This motivated the construction sector – in general, showing low productivity growth – to invest in R&D, new technologies and processes to become more competitive and adapt their technical offers and service levels in renovation solutions.”

Energiesprong refurbishments uses technologies such as prefabricated facades, insulated rooftops with solar panels, and smart heating and cooling installations. From top to bottom, renovation projects in Oud-Vossemeer (NL), Nottingham (UK), Gorredijk (NL). Photos: Energiesprong

Most importantly, Energiesprong represents great value for the residents: there is no energy bill anymore and the home has a 30-year performance warranty on both the indoor climate and the energy performance. Thanks to prefab elements and efficient processes, the renovation works take around 7-10days, sometimes less. Annually, a net-zero energy house generates enough energy to heat the house, provide hot water and power its household appliances. This means that the money that is usually spent on energy bills and maintenance work pays for the upgrade. The whole operation is cost neutral, at worst, for the tenants. The residents get a fully renovated, much better looking, warm and comfortable home at the same (or lower) cost of living. “These are key drivers for tenants to accept the temporary annoyance and go through the whole process.

Again, this does not happen automatically and still requires close personal contacts and thorough preparations (meetings, documentation, help desks) from housing professionals.”

Interestingly, Energiesprong views the social housing sector in each market as the launch pad for these solutions, with a view to later scaling to the private home-owner market.

People at the HEART of housing

Despite the multiple policy and environmental drivers, “not everyone believes that it will be worth while to renovate” notes Garnier. That’s why careful consideration of the social aspect, putting people at the center by involving them more closely in tackling challenges such as deep renovations, is of paramount importance to Housing Europe and its members.

As well as HEART, Housing Europe is involved in another Horizon 2020 project Triple A Reno. “We are working on a guide to inform housing providers about the best practices during the different stages of renovation (before, during, after), with pointers for building owners and project managers to show them how to involve residents in the decision-making process and during the whole ‘user journey.”

This is an eminently practical move, as the tenants’ agreement is often required for major renovations. The issue is magnified in the case of mixed tenancy or multi-family home-ownership – “whether these threats are real or perceived, nonetheless, residents fear costs, comfort, intrusion, and other hindrance as a consequence of renovation,” says Garnier.

The overarching goal, according to Garnier, is to show that “technical improvements should follow social and human needs – not the other way around.” The research underway focuses on the acceptance and satisfaction levels of residents, and initial results from the residents of the HEART test case building in Reggio Emilia have already yielded some interesting points.

Although most residents are over 60, many are keen to improve the energy efficiency of the building and, con-trary to popular belief, environmental considerations play a role as well. The residents surveyed reported a strong belief in the ability of new technology to improve comfort and efficiency, although a strong need for user control was noted as well.

This highlights an interesting contrast, notes Garnier. “This typifies a very interesting discussion in the context of smart homes,” he says. “HEART uses very sophisticated systems to regulate energy, track comfort levels, measure humidity and so on. We need to understand how to increase acceptance and satisfaction of residents while taking into account the trade-offs in terms of energy efficiency, health, freedom of choice, empowerment and privacy. This is a difficult exercise with many influencing factors.”

The greatest potential of the HEART toolkit, according to Garnier, will be realized if the project achieves a certain scale on the number of buildings throughout Europe using the cloud-based system for ongoing management and optimization of the algorithms controlling the energy systems. In addition, the integration in one single toolkit of the different technologies is an important aspect – “this has the potential for cost efficiencies from packaged systems and in turn this could increase the market share for renewable technologies”, he says.