CBAM: EU Protectionism or Landmark Climate Policy

What is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and how is it going to change trade globally?

The European Union (EU) has developed the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – a landmark tool that will impose a carbon levy on materials imported from non-EU countries that may not meet European sustainability standards.

Carbon leakage refers to the potential scenario in which businesses might shift their production to countries with less strict emission regulations due to the cost implications of climate policies. This could happen to avoid higher expenses associated with reducing carbon emissions in their home countries.

To achieve its objective of reducing carbon leakage in high-risk sectors such as cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, as well as electricity and hydrogen, CBAM will operate in conjunction with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), which was established in 2005 as the world’s first international emissions trading system.

The ETS, alongside CBAM, aims to prevent a scenario where manufacturing activities with high carbon emissions relocate to countries with less stringent or lax environmental regulations. Consequently, CBAM will reinforce the principles of responsible production and consumption, reducing the environmental burdens associated with the manufacturing process.

By implementing CBAM, the EU will verify that a payment has been made for the carbon emissions generated during the production of specific imported goods. This mechanism will ensure that the carbon price applied to imports matches the carbon price applied to domestically produced goods. As a result, the EU’s climate goals will remain intact, and there will be no undermining of the region’s efforts to combat climate change.

The introduction of CBAM by the European Commission is perceived in two different ways.

CBAM is first and foremost a climate policy.

Domien Vangenechten, Senior Policy Advisor at E3G

According to Max Gruenig, Senior Policy Advisor at E3G, though the European Union perceives CBAM primarily as a domestic climate policy aimed at curbing carbon emissions and accelerating both national and international investments in greener manufacturing, the rest of the world views it as a trade policy with potential implications for global trade dynamics.

This manipulation of global trade could also be seen as using climate policy to implement a new kind of neo-protectionism.

What is the EU doing to implement the CBAM?

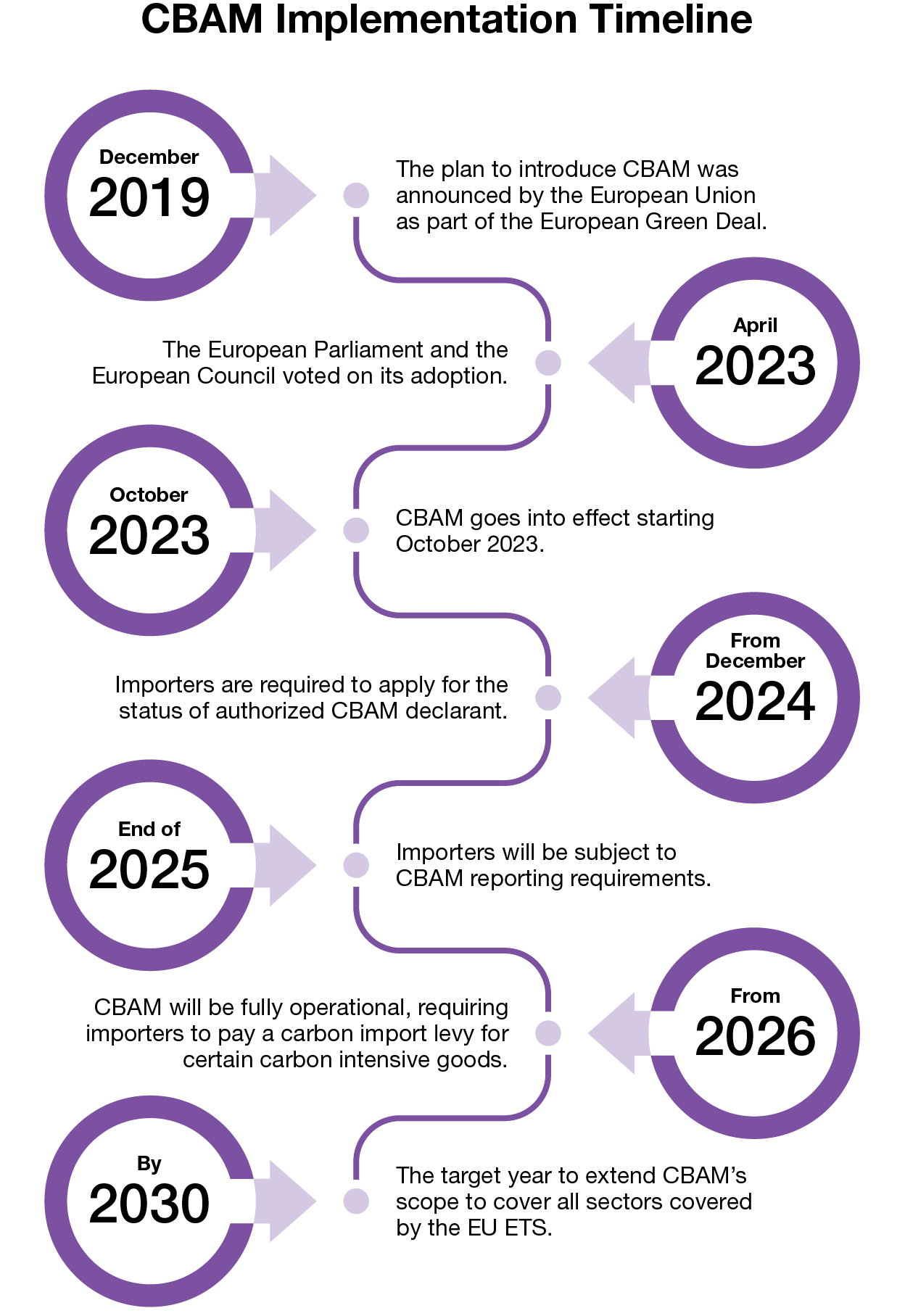

From one standpoint, Yan Qin, Carbon Lead Analyst at London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG), states that the final design of CBAM, as agreed upon during the legislative process, has been carefully balanced to address various concerns. One notable aspect is the incorporation of a three-year transition period, starting in October 2023, which will require the importers of goods covered by the new rules to report embedded greenhouse gas emissions without any financial payments or adjustments.

Initially, CBAM will target imports of specific goods and precursor materials known for their carbon-intensive production processes and high risk of carbon leakage. Qin adds that CBAM demonstrates its commitment to fairness by considering free allowances for certain sectors. This is good news for exporters with carbon-intensive production methods, as it helps create fair competition and avoids putting too much pressure on their businesses. The gradual phase-out of EU ETS-free allowances also benefits exporters because it means that the rise in carbon costs will happen slowly over time, preventing sudden and disruptive changes.

When viewed from a climate justice perspective there is a different opinion. EU Policy Manager at EPICO KlimaInnovation, Sam Williams, points out potential disparities in the design that might not fully address fairness and equity concerns, especially when considering third countries’ vulnerability to climate change and their historical responsibility for emissions.

A more nuanced design of the CBAM, considering third countries’ responsibility and vulnerability, may have helped to ensure a fairer and more equitable implementation, Williams adds. The EU urgently needs an effective carbon levy that maintains the competitiveness of EU industry and helps green global value chains.

Measuring countries’ exposure to CBAM, based on various factors such as trade with the EU, emissions intensity, and their economy’s reliance on the production and trade of goods included in CBAM, Williams states that many vulnerable countries, less responsible for, yet most impacted by climate change, might face significant impacts.

Developing economies hit hardest by EU’s carbon border tax

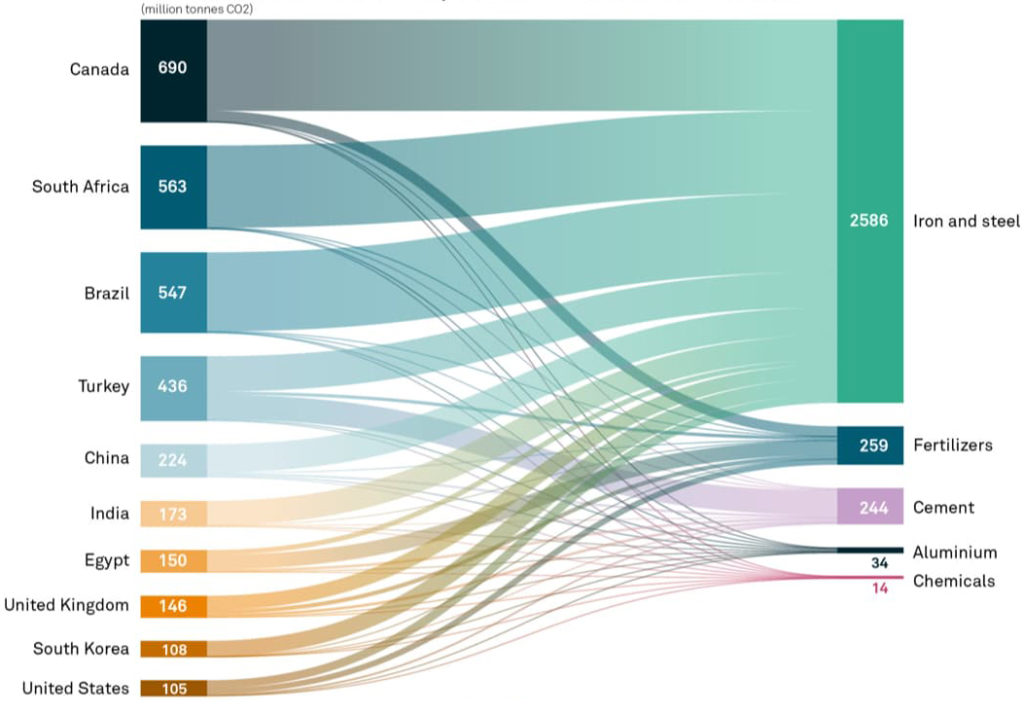

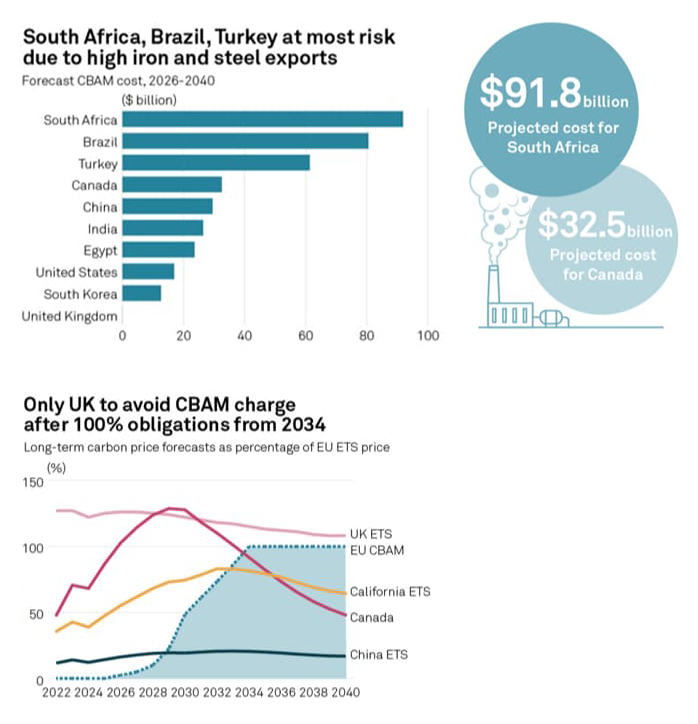

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is set to have far-reaching impacts on world trade and the wider energy transition. Phasing in from 2026, CBAM will levy a carbon tax on imports of selected energy intensive materials and products into the EU, removing the gap between the EU’s ETS carbon price and the export country of origin’s carbon price. Analysis by S&P Global Commodity Insights shows Canada, Brazil, South Africa and Turkey will be most exposed to the mechanism, with iron and steel by far the biggest sector targeted.

The countries and sectors most exposed to CBAM All data 2026-2040 totals

How can the EU engage with countries outside of Europe?

While pursuing common rules through multi-country coalitions is a definite step forward, unilateral measures such as CBAM risk overlooking the significance of country-specific issues and single variables that shape vulnerability to, and responsibility for climate change, says Sam Williams.

There is a fear that CBAM may primarily affect a select few countries, potentially creating conflicts. This issue is often interpreted by many other countries as a form of neo-protectionism, which can involve a variety of trade restrictions. However, the intention of CBAM is quite the opposite, Domien Vangenechten, Senior Policy Advisor at E3G, suggests. Its aim is to ensure equal treatment between domestic producers and importers, rather than granting an advantage over foreign competitors. According to Max Gruenig, the benefits of CBAM for the EU are relatively minimal, serving more as a political tool to phase out free allocations rather than significantly impacting global emissions or competitiveness within the EU.

Yet the focus solely on carbon pricing may not be the remedy for every nation’s climate challenges. Instead, a more nuanced and collaborative approach is required, where the global community comes together to explore diverse strategies and solutions that align with the unique realities of each country.

Varying impacts of CBAM

China will be one of the hardest countries hit by the EU’s carbon tax. China’s climate envoy and Ministry of Commerce perceive CBAM as a unilateral measure and trade barrier, something expected by the EU. Consequently, CBAM was meticulously designed to align with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, thereby minimizing the impact of potential disputes on its implementation.

Acknowledging the importance of constructive dialogue and engaging with Chinese stakeholders remains crucial to ensure that CBAM discussions are positioned within the broader context of global climate negotiations.

Chinese policymakers are using CBAM as an external factor to force its own industry to speed up decarbonization efforts. China has committed to carbon peak and neutrality goals, so it is determined to transform its carbonintensive industry. Considering this perspective, the risks to CBAM are perceived to be limited.

One of the primary goals of CBAM is to encourage more countries to implement carbon pricing. In this regard, when CBAM can exert pressure on China, accelerating the nation’s establishment of its national ETS and including its aluminum and steel sectors in its ETS, this goal of CBAM will be fulfilled, Yan Qin says. Moreover, it is possible that the sectoral expansion of China’s national ETS might mirror the evolvement of the EU CBAM too, watching which sectors will be covered in EU CBAM regulations next.

Max Gruenig, Senior Policy Advisor at E3G, underlines the concerns raised by middle and developing countries in emerging markets. He argues that the EU’s efforts to establish a level playing field may inadvertently hinder their own development. These countries feel pressured to quickly meet the EU’s environmental standards, but their emissions and development paths are overlooked. In Gruenig’s view, a more understanding and accommodating stance from the EU could go a long way in fostering equitable global collaboration.

Hitting developing countries hardest

Despite the potential successes in pushing the energy transition forward, CBAM would disproportionately affect developing economies, especially in Africa and the Middle East, exacerbating economy induced social issues such as gender inequality, education levels and disparities between suburban and rural areas. Lower-income countries heavily reliant on fuel exports, like Cameroon, Egypt, and Nigeria, along with other African nations such as Ghana and Morocco, would experience a more significant impact. For instance, Mozambique, responsible for over 7% of the EU’s total aluminum imports, is often cited as a prime example of the potential ramifications.

CBAM serves as a poignant reminder that a unilateral one-size-fits-all approach might not effectively address the diverse needs and circumstances of countries worldwide. CBAM alone cannot reduce global emissions in a climate just manner.

Sam Williams, EU Policy Manager at EPICO KlimaInnovation

Turkey is the EU’s third-largest exporter of carbon-intensive goods, making its aluminum, electricity, cement, and iron and steel industries particularly exposed to EU financial levies and taxes when CBAM is implemented in 2026. Without cutting carbon emissions, these sectors could face significant carbon taxes on their exports to the EU.

When CBAM is implemented in 2026, importers will face new financial obligations, and the free allowances provided through the ETS will gradually decrease. This change is expected to be mirrored in Turkey, leading to higher carbon prices within the EU and a more significant impact on the country.

Given the weight of Turkey’s exports, investing in green transformation becomes crucial at this stage, the former Ambassador of Turkey and the Ex-Chairman of the Executive Committee of the OECD and Chief Climate Change Negotiator, Mithat Rende, says.

While some countries are gearing up to implement their own carbon pricing initiatives, there is a prevailing notion that the design of CBAM lacks nuance and fails to adequately consider the vulnerabilities of countries with limited resources. Targeting heavy polluting players, even in developing countries, without hampering more vulnerable sections of society that are less responsible for climate change, should be the path that we should follow, Williams adds. In a scenario where this is not considered, implementing this mechanism may not achieve a fair and equitable outcome for all parties involved.

The future of CBAM

A revision of CBAM is expected in 2026. Depending on the political composition of the next European Parliament from 2024, there is a realistic chance that the current roadmap could be reversed at some point, given the viewpoints of the potential next EU legislature.

If CBAM and the phaseout of free allowances create extra burdens for EU industries, such as stricter rules on the carbon footprint of imported goods, additional supportive policies could contribute to achieving the climate and sustainability objectives of CBAM.

But cooperation with third countries is of paramount importance in ensuring that these countries are not left behind in both the energy transition and global development.