Building a Bio-Based World

To realize the potential of the European bioeconomy, social perceptions of recovered resources need to change.

Europe has positioned itself successfully as a global pioneer in the development of novel bio-based and circular industries, alongside bio-science and technology leaders such as Japan and the United States. For Europe, the bioeconomy represents an opportunity to solidify the Continent’s position as a leader in bio-based industries and processes.

In 2012, the European Union introduced its Bioeconomy Strategy with transversal impacts across key sectors including energy, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, waste and water management, among others. In 2018, the Strategy was updated to respond to new EU policy priorities, including those outlined in the updated Industrial Policy Strategy, the Circular Economy Action Plan, and the Communication on Accelerating Clean Energy. For the EU, a successful European bioeconomy “needs to have sustainability and circularity at its heart. This will drive the renewal of our industries, the modernization of our primary production systems, the protection of the environment and will enhance biodiversity.”

But first, what is the bioeconomy?

The bioeconomy encompasses all sectors that rely on biological resources (animals, plants, micro-organisms and derived biomass) to provide products, energy, and services. This includes primary sectors agriculture, forestry, fishing and aquaculture, as well as those dependent on the resources they produce to make food, feed, and bio-based energy and products. A sustainable bioeconomy is one that reduces pressures on natural resources and takes planetary boundaries into consideration to enhance and safeguard the functioning of our ecosystems and thus the ecosystem services upon which society relies.

5 Goals of the EU Bioeconomy Strategy

- Ensure food and nutrition security

- Manage natural resources sustainably

- Reduce dependence on non-renewable, unsustainable resources

- Limit and adapt to climate change

- Strengthen European competitiveness and create jobs

Source: EU, 2018

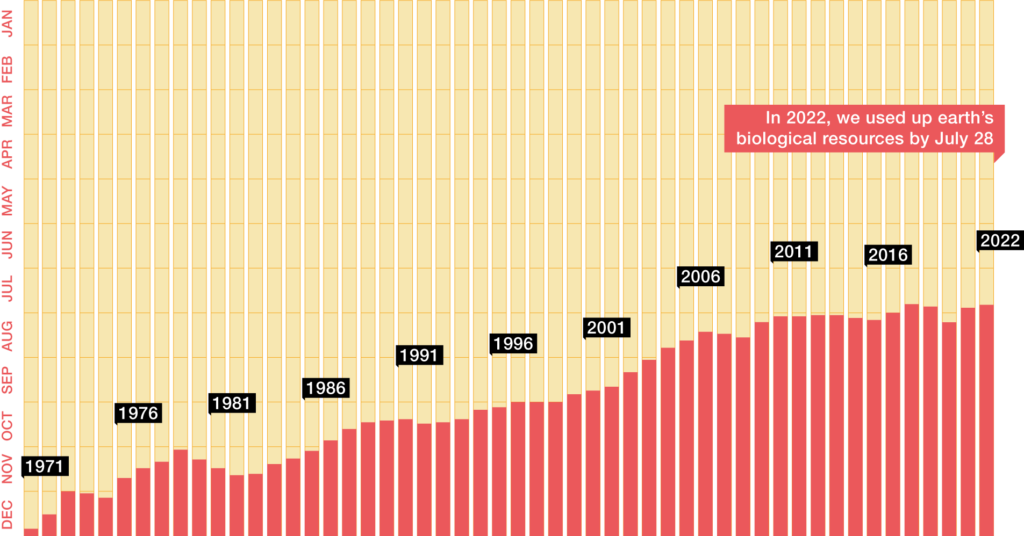

In 2022, the world had depleted an entire planet’s worth of resources by July 28. By the end of the 2022, we used the equivalent of one-and-three-quarter planet’s worth of resources; a 75% increase since the start of the 1970s. And yet, to meet the growing global demand for agricultural products we will need to produce sustainably almost 50% more food, feed and biofuel by 2050, as compared to 2012 levels.

Ecosystem Services and Planetary Boundaries: Two terms to help understand and improve our relationship with nature.

Ecosystem services are the benefits that nature provides to society and that underpin all economic activities. They are often categorized as four types:

- Provisioning services: Benefits to society from the environment including supply of food and water resources.

- Regulating services: Benefits to society through the regulation of ecosystem processes such as soil and air quality, flood control, and crop pollination.

- Supporting services: Services that are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services such as providing habitats for plant and animals and preserving biodiversity and genetic diversity.

- Cultural services: Non-material benefits people derive from nature including spiritual well-being, cultural identity, aesthetic and engineering inspiration.

Planetary boundaries:

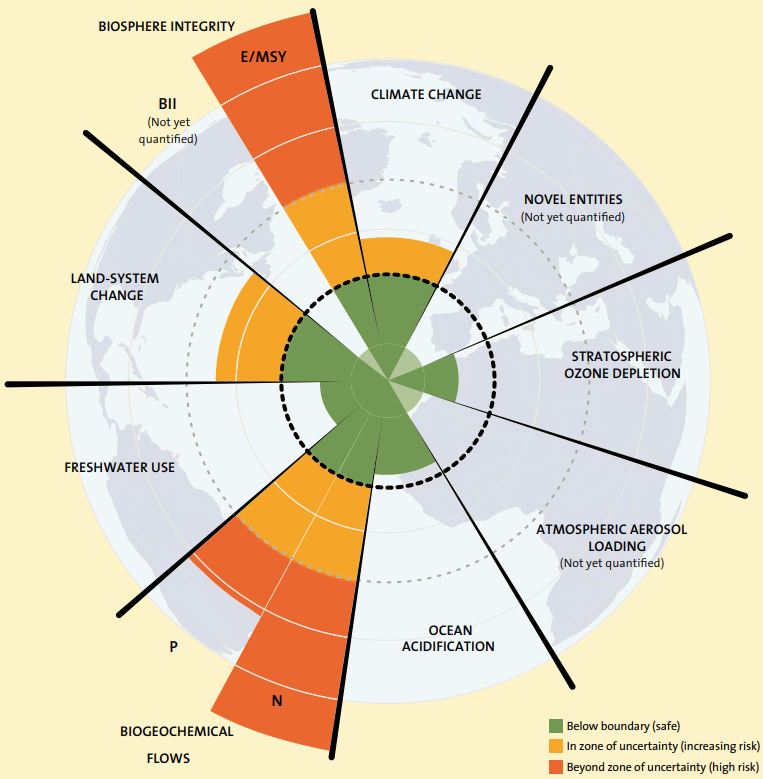

First proposed in 2009, the planetary boundaries concept identified nine planetary life-support systems that underpin life on Earth as we know it. For each boundary, safe operating spaces have been defined. Living outside of these boundaries threatens the resilience and stability of these life-supporting systems and thus the continued functioning of vital ecosystem services that support our lives and economies. We have already passed safe thresholds for four of the nine boundaries, including climate change.

How can the bioeconomy help resolve this disconnect between what society needs and what the planet needs? The challenge is even greater still when we consider that primary production such as agriculture that is linked inherently with the boundary whose threshold we have long passed (nutrient cycling) through the application of nitrogen and phosphorous-based fertilizers.

How can nature provide food for ten billion people without putting further pressure on planetary boundaries and threatening the ecosystem services upon which we rely?

Biomass: sustainable production and circular recovery

There are two options for sourcing biomass for the bioeconomy: Cultivating biomass through primary production and recovering it from secondary waste streams.

As we are already using more resources than the Earth can offer and we are pushing planetary boundaries in terms of land-use change and nutrient loading, scrutiny of what sustainable biomass production looks like is to be expected.

In the realm of bio-based energy, forestry advocates have been criticizing the EU regarding the threat to European and global forests posed by the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and the classification of woody biomass as a carbon-neutral feedstock. A 2021 report highlighted five cases within and outside the EU’s borders that demonstrate how the sustainability criteria in place do not impede “destructive biomass” production. In September 2022, following a three-year campaign to urge the EU to declassify woody biomass as a renewable carbon-neutral energy source, the European Parliament voted to uphold the classification. The vote came as a blow after earlier victories in 2022 including a “historic breakthrough” with the introduction of new rules of what will be counted as “sustainable” biomass.

Debates about the sustainability of other primary sectors are also taking place: In February 2023, over 250 organizations shared an open letter urging the European Commission (EC) to “keep environmental and social sustainability at the center of the policy debate around food, agriculture and fisheries” during the development of the legislative Framework for Sustainable Food Systems (FSFS). The FSFS has a core objective of promoting “policy coherence at EU level and national level, mainstream[ing] sustainability in all food-related policies, and strengthen[ing] the resilience of food systems […] to accelerate and make the transition to sustainable food systems easier.”

It goes (almost) without saying that sustainable biomass production and what it will look like in our climate-neutral future is still up for debate.

So, if not new resources, why not old ones?

Finding the value in waste

Valorizing waste is the “process of reusing, recycling or composting waste materials and converting them into more useful products including materials, chemicals, fuels or other sources of energy.” It offers the opportunity to support climate action by reducing landfill and incineration-based emissions and pollution, reduce pressure on natural resources and dependence on fossil-based resources while developing new markets and products to invigorate local economies.

Each year, 2.153 million tons of waste are produced in the EU by all economic sectors – equivalent to 4,813 kg of waste per person, with only 38% of all the waste produced in the EU being recycled in 2020. This includes all solid waste from all economic sectors, including households, which make up almost 10% of total solid waste production.

For the circular bioeconomy, biowaste – mainly food and garden waste – is a key waste stream to create high-quality bio-based products. At more local levels, biowaste makes up the single largest component of municipal waste, representing 34% of municipal waste collected, making addressing the biowaste challenge central to reaching the EU’s 65% recycling target for municipal waste (in 2020 this figure was 39.2%) by 2035. If collected properly, treated biowaste offers a domestic supply of resources for food, feed and bio-based energy and products, reducing EU imports and creating new economic opportunities.

The value in waste may be clear, but the entry of bio-based products into the market is a sensitive issue. There are new technologies, products, and services that touch health and safety, as well as some products’ significant “yuck” factor to consider. Proposing insects for food or feed or bio-based products, such as those made from recycled feminine hygiene products, have additional barriers from social norms and conventions which can hinder their use.

Old habits (and attitudes) die hard

While the term “bioeconomy” omits the social dimension, social aspects have a large role to play in the development (and acceptance) of bio-based products, from engagement in food waste sorting and reduction strategies to the consumption (or not) of bio-based products.

A key challenge to increasing biowaste recycling rates in plastic contamination, which cause biowaste to fall short of quality criteria required for composting and other upcycling processes. As part of the 2018 revision to its Waste Framework Directive, the EU adopted stricter rules on separate waste collection (including biowaste) to go into effect by December 2023. Putting overarching systems in place help provide parameters and public administrations are interested increasingly in finding ways to foster waste sorting behaviors.

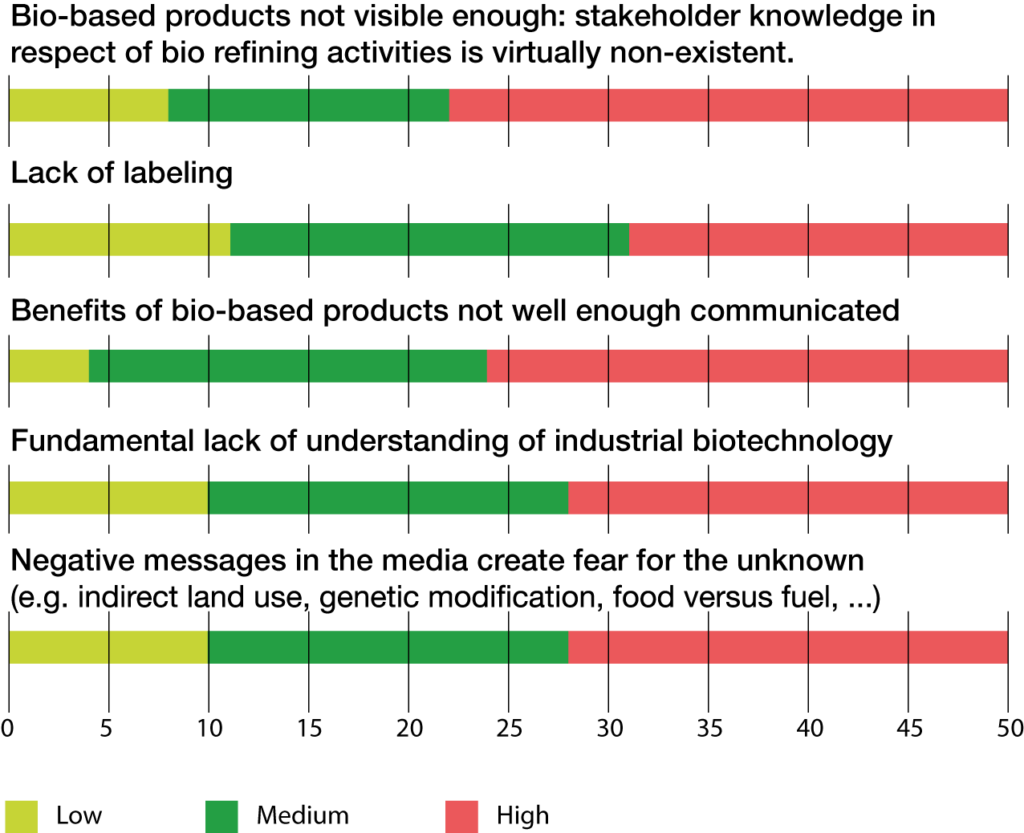

At the consumer end, a survey conducted by BioBase4SME found that stakeholder perception barriers were the second most important barrier to bio-based Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in North-West Europe, after demand-side policy barriers. Over half of the SMEs surveyed found lack of stakeholder knowledge (such as the difference between biodegradable and bio-based plastics) and proper communication of the benefits of bio-based products to be high barriers to their businesses.

Stakeholder Perception Barriers

Suggested barriers in the category of stakeholder perception barriers with the number of SMEs that scored the barriers as low, medium or high.

Changing hearts and minds to enable the circular bioeconomy

At REVOLVE, fostering cultures of sustainability is quite literally our business, and we make it our business to work with projects that do the same.

On one side of the recovery equation – the resource side – for bio-based industries, the EU-funded HOOP project (aiming to vitalize the urban bioeconomy) is finding new ways of reaching out to stakeholders and interested citizens. Through regular Biowaste Clubs in eight Lighthouse cities across Europe, HOOP is bringing people together to develop a shared vision for how their city can become more circular. Harnessing the power of technology and citizen science, HOOP has also developed a citizen science app that uses gamification to engage users on an interactive journey to discover the potential in circularity. The app shares knowledge about proper waste sorting and the potential of the urban bioeconomy while gathering data on specific research questions from each of the eight Lighthouses to address during Biowaste Clubs. These findings are then shared with cities and regions across Europe through the HOOP Network.

On the output side of the equation – bio-based products – the EU-funded FER-PLAY project is conducting social acceptance surveys (be part of the findings! visit: fer-play.eu) to unearth potential challenges and to help biobased businesses address consumer concerns. As part of work to increase the production and uptake of alternative fertilizers made from secondary resource streams, FER-PLAY aims to replace conventional fertilizers (rich in nitrogen and phosphorus) with alternative ones (like compost and manure) to help prevent water and soil contamination, mitigate emissions from the agricultural sector, and improve resource independence. This will promote the development of the circular bioeconomy at local and regional levels – but only if farmers buy them (and only if we continue to buy their products).

The big picture: a just transition

For many, the concept of sustainability is fundamentally a debate about how to realign economic and environmental goals, giving nature’s needs the same weight as those of our economy. But that understanding leaves out the human dimension. The letter to the EC regarding the FSFS emphasized both, and a 2022 report from the McKinsey Global Institute underscored the social barriers to the transition to a net-zero economy. According to the report, the green transition could create 200 million jobs and provide a host of environmental and economic benefits in Europe for generations to come. Similarly, 185 million indirect and direct jobs could be lost, with reverberating impacts for local communities across Europe. In this scenario, considering the social dimension means ensuring the transition leaves no one behind.