Afghanistan: Kalashnikov Society

After a decade, nowhere in the world has the western model for exporting democracy failed more spectacularly than in Afghanistan. Confronted by a resurgent Taliban and allied to a corrupt central government, this is now the longest war in u.S. history – and it has spread to Pakistan.

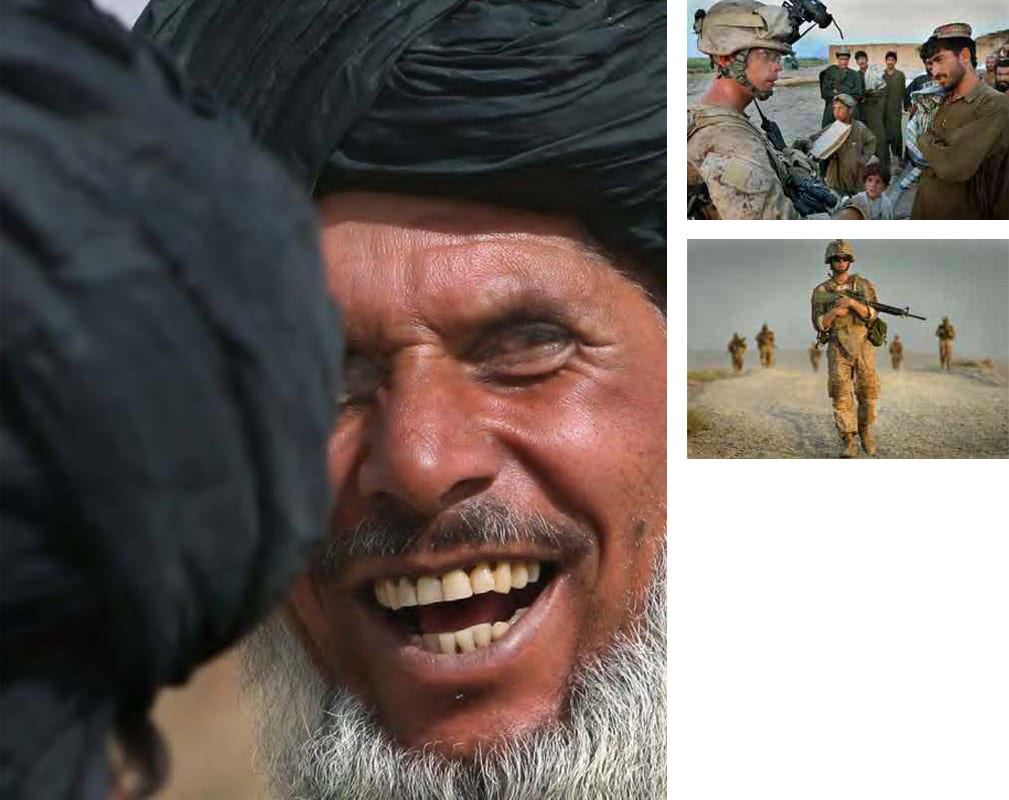

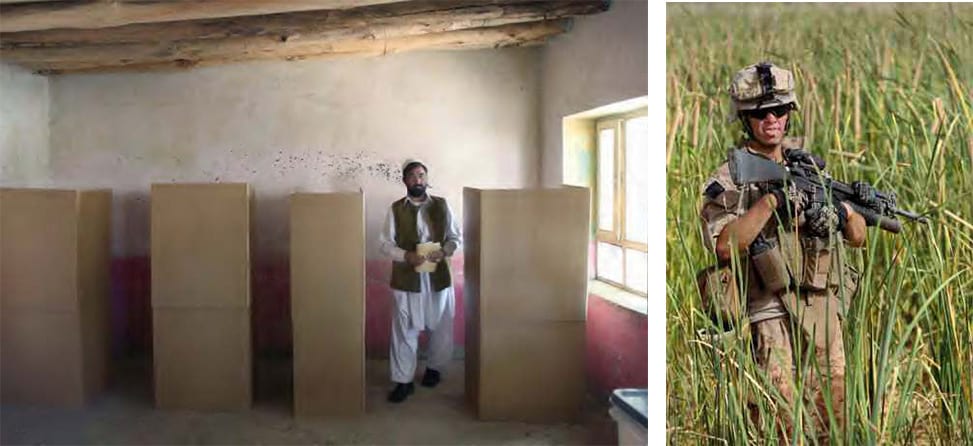

Five years ago, President Hamid Karzai issued an official decree essentially outlawing political parties, which explains why the voting booths set-up for the latest afghan parliamentary election looked so deserted. The “Free and Fair” election in the midst of all-out war was policed by no less than 200,000 members of afghan armed forces, plus tens of thousands of NATO soldiers. Paradox gave way to shameless swindling in this fascinating theatre of democratic absurdities. The trouble is that the greater the fiasco of exporting democracy is proving to be, the more doggedly the west is striving to make it happen. Throughout the long and violent history of these lands, the systems of governance imposed from without have turned out to be potentially lethal assaults on the region’s most basic stability. This time is no different. Last year’s presidential election in afghanistan was marked by an abundance of cheap swindling and the incredible impotence of the international community as it gazed upon a monster of its own creation.

When the Taliban regime fell, my heart was filled with joyful expectation. Now it’s 2010 and the situation is only getting worse. Any- where you look, all you see is trouble. We’ve had many casualties and many more people are bound to die. In every conflict like this, the heaviest price is paid by the women and children – even more so in Afghanistan where the position of women is worse than elsewhere in the world. As the president of the Red Crescent, my job is to be as neutral as possible. Every day I meet victims of our countless mistakes. Our organisation has spread across almost 90 percent of our territory. This is the kind of access no one else has. Everyone is putting their faith in us. This is why every minute out of every day I am in direct contact with Afghan realities. I never discriminate: I am determined to give the same care to a wounded Taliban soldier as I would to a wounded member of the government forces. In the current situation, I can do far more as a humanitarian worker than I could as a member of the Afghan parliament. I hear that the authorities are now negotiating with the Taliban. This is unfathomable to me. Is this what we have been fighting for? Are we just going to give up after so many people died? Peace always takes some honest compromising – but the sort of peace that is arrogant enough to dictate terms is no peace at all. When we were governed by the Taliban, things were pretty quiet, but the entire country was turned into a giant prison. What will they expect us to give up if the government and the Taliban strike a deal? Women’s rights? Free speech? Our future?

Fatima Gailani, President of the red Crescent

The Surge Strategy

The sky above Kandahar is crowded with bombers, gunships and military transport planes. In this province, the long-awaited NATO offensive never officially began. At the moment, no less than 20,000 U.S. troops are fighting the Taliban here. Kandahar is widely considered to be the womb of the Taliban movement. The U.S. forces are determined to pursue a new strategy as envisioned by the ISAF chief commander General David Petraeus. Petraeus’ predecessor, General Stanley McChrystal, was forced to step down in June 2010 for being too honest. For a long while, Mc Chrystal was planning a great offensive into the territories now totally controlled by the Taliban, tribal militias and opium dealers. McChrystal’s plan was based on a close cooperation with the Afghan security forces as well as the support of the local tribal leaders. But in April 2010, after the tribal elders met President Karzai in Kandahar, McChrystal’s plan was discarded. The elders spoke vehemently against any forthcoming NATO offensive – so President Karzai, knowing that additional civilian casualties would further weaken his grasp on power, publicly stated that, were an offensive to take place, he would back the insurgents. Moreover, the elders made an appeal to the members of the government forces to disobey the orders of foreigners. This put the U.S. in a predicament: at some crucial juncture, the government forces could very well turn against the foreign occupying forces. Fortunately for the U.S. forces, the Afghan troops are weak, inexperienced and poorly motivated.

For a number of years, General David Petraeus served as the commander of U.S. forces in Iraq. When he moved on to subdue Afghanistan after Iraq, Kandahar saw an escalation of military intervention. The goal of these manoeuvres was to gradually retake a number of key strategic points in the province. But the NATO mission failed to heed the lessons learned so brutally by the former Soviet invaders. General Petraeus was determined to apply his ‘Iraqi doctrine’ on Kandahar as well. The idea was literally to buy the cooperation of local militias – but what worked moderately well in Iraq didn’t at all in Afghanistan. Afghan tribal ties and local traditions are much stronger. U.S. strategists should have read more history to learn that you simply cannot buy an Afghan fighter. The best you can hope for is to rent him for a while – which is essentially like playing Russian roulette with your troops. As the U.S. wasted more substance on this will conceived venture, the Taliban regrouped and spread out across the province. The U.S. had been counting on at least some modicum of local support, but now they found themselves caught in a mousetrap and the casualties began to pile-up.

“I don’t think anything can surprise us now,” says Ahmad Khan, a local tribal elder, sitting in a tea-house at the city bazaar in Uruzgan province. “For more than thirty years, we have known only war. All of those who came here were driven out. Our province is special, you must understand. We are an extremely independent people. We have always lived like our Pashtun brothers in the Pakistani tribal lands, but now both the Americans and the Taliban are trying to force themselves on us. Both are set to boss us around, and now the people here are angry – hardly a day goes by that is not marked by heavy fighting somewhere nearby. We want peace, but the Americans are shelling our mountain villages and the Taliban are raiding them for supplies. We fear the Taliban – we are not ignorant, we know what goes on elsewhere in Afghanistan… But let me tell you, there is nothing that we fear more than the American bombs.”

Bravo Company from 1st Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Division of the U.S. Army descends from the hills above the Tsekzu village in the Urzugan province. The soldiers make their way down slowly. All of them know they are treading on enemy territory. The unit has never entered the village which lies in the middle of seemingly endless cannabis fields. Amid its desert surroundings, the plant’s jaunty green color strikes everyone as simply surreal. The scorching sky is scratched by lowflying Apache helicopters. The intelligence gathered from the ‘not-very-reliable’ Afghan police suggests this is the ‘special’ type of village where both U.S. forces and the Taliban are unwelcome.

“I’m getting seriously fed up with this,” Sergeant Nagy, 22, says as we make our way down the goat-trail. “If you ask me what the hell we are doing, I couldn’t tell you why the hell we’re here. Every day is the same. Nothing ever changes. The people here hate our guts and we keep trampling gardens and orchards in full battle gear. One of these days, we’re sure to get our asses kicked.” As we walk on, Sergeant Nagy starts running out of breath. The morale of the men is low and depleting. The platoon is coming back from two days of patrolling terrain that counts as no-man’s-land during the day, and is ruthlessly dominated by the Taliban at night.

Lieutenant Dewey, the platoon commander, warns us to keep our heads as low as possible. This is sniper territory. “Above all,” he rasps: “you need to scan in all four directions at once. And don’t forget to scan for the mines under your feet. Watch each other’s backs, okay? We could be attacked at any minute. We’ve never been here before. The people here don’t know us. They have absolutely no reason to trust us.” Lieutenant Dewey is 26. His men’s faces are etched with anxiety. After nine years of war, it’s getting increasingly hard to find a suitable motive to keep doing this.

The village is spread out over part of the valley. Instead of a welcoming committee, the U.S. soldiers are met by a few barefooted village children. The soldiers are much too alert to feign goodwill. We enter the cannabis fields and joke about how the smell reminds us of a high-school toilet. Irrigation ditches nearby are completely dry. Here and there among the clumps of weed, you can find tiny huts made of dried mud with gaping holes instead of doors and windows. Anyone who knows anything can tell this is a perfect place for an ambush.

Every sound makes the soldiers jump. Wali Mohammed, a major with the Afghan police, is very nervous. Major Mohammed is a tribal elder who demanded a pair of new combat boots to join the U.S. troops in patrolling the village. The children are making fun of him, but he is not allowed to slap them around to get them in line. The platoon assumes its tactical formation as it enters the heart of the village where everyone is expecting a Taliban ambush, and halts for a minute as a hot breeze stirs the fields of hallucinogenic greenery. Then a loud boom is heard from the neighbouring hills, followed by several more. U.S. artillery is providing back-up. “Move on!” crackles the command over radios.

A group of U.S. soldiers is slowly advancing down the dusty road. The beginning and the end of the column are marked by a man aiming a machine-gun at gawking passers-by who do not seem to care. “Stop every vehicle the moment you see it – the very instant!” Lieutenant Dewey orders. Here, the possibility of a suicide attack is very high. In these demented times, when terror is waging war on terror, suicide attacks have become a way of communication on the battlefield. Death lurks everywhere, all the time. The U.S. Army built its confidence on hi-tech fire-power, but in guerrilla warfare there is no tolerance for hubris.

Waiting for the taliban

As the U.S. soldiers step into the village, the bustle grinds to a halt. Old men, drinking tea and smoking home-grown tobacco in the shade, glare at the infidel invaders. “Greetings. What do you want from us?” Haji Ahmadamou, a village elder, asks them. The Afghan interpreter for the Bravo company tells the old man that they would like to know whether the village is frequented by the Taliban. If so, they would like to know for what purpose. Admirably cool-headed, Mr. Ahmadamou replies that the Taliban have come to Tsezku several times to collect money, food, fuel and clothes. Never once, he adds, did they kill, hurt or kidnap anyone. The village elder then strikes up a conversation with Major Mohammed who had joined this patrol in order to ‘make a good impression’.

“The Taliban here are mostly local boys from the neighbouring mountain villages,” Major Mohammed says. “They are different from the Taliban in Helmand or in the east. The fighters here have family ties with the villages so most of them do not attack the locals. What could they possibly get out of it? So far, the local Taliban had only been fighting the foreign soldiers. Foreigners have never been welcome here. Every time they came, they brought war with them.” The major is being less than truthful. In the hills and valleys patrolled by U.S. troops south of Tarin Kowt, the Taliban have attacked checkpoints manned by the Afghan police and took control of several of these checkpoints. Since the Dutch-trained policemen are operating ‘independently’ here (meaning cut off from the rest of the world), the Taliban have gained a lot of ground. The local police have been known to aid them by supplying weapons and Ford Ranger vehicles. The last three months have been the most depressing times for the international forces since the Taliban regime fell in November 2001. The casualties among foreign soldiers are almost fifty percent higher than among Afghan security forces.

“This is Taliban territory,” says Lieutenant Thriplett. “They control the hills and the green strips along the river that the Afghan security does not dare patrol because they’d get lynched.” Thriplett was the leader on the daylong patrol we just ended. During the patrol, his men dug into the trenches and pointed their weapons at the village two kilometres further on where a few hours ago a Taliban attack was repelled. After the Taliban determined that the U.S. forces were too strong, they scattered. Two insurgents were killed in the attack. As the big guns from the nearby artillery outpost start ripping the sky, the U.S. soldiers became worried and confused. “Dammit, I hope this doesn’t land on our heads!” Thriplett yelled at one point. “I’m pretty sure the guys doing the shelling have no idea we’re down here.” During the last few weeks, Thriplett’s men had been taking part in various skirmishes on a daily basis. “I don’t want to die from friendly fire!” one of the soldiers howled while desperately seeking cover. The 155 mm shells kept shrieking above our heads. Their targets were located a few hundred meters from our position and the ground shook.

Most of the young Afghan policemen seemed unperturbed by the shooting. In general, they tend to avoid any form of combat since they are so inadequately armed and so poorly trained. They hid behind the marijuana plants, smoking, drinking tea and smiling. The sound of war has long become the soundtrack of their lives. “Every day it gets worse,” Major Torjan Nachin says just before the American shelling starts again. “The Taliban are getting ever stronger. There is nothing we can do. The people here are afraid of them so they won’t tell us where they’re hiding. The Taliban are taking away their food, clothes and money. In the last few months, a lot of the young men disappeared from the villages around here. Now they are fighting for the enemy.” Nachin commands a small police outpost in the village of Setrbaba. A week ago his vehicle drove straight into an ambush. The driver was killed and two policemen were badly wounded. Nachin, miraculously, walked away without a bruise. “I guess someone up there really likes me!” the bearded major beams. So far, the Taliban made three direct attempts to assassinate him. The bomb they planted recently took out his house. Despite his nine lives, Major Nachin – like most of the Afghan policemen around here – refuses to wear the official uniform. He also refuses to join the U.S. forces in patrolling the local villages. As long as the police refrain from upsetting the routine of the villages, the Taliban mostly leave them alone.

“It’s going to be a while before we can start to rely on any sort of effective cooperation with the police,” Thriplett muses. “But in the long run, it is the only chance we’ve got. Sooner or later, we’re bound to leave this place. Our job is to make sure that when we do, the entire country doesn’t get overrun by the Taliban in a matter of days. Our aim right now is to avoid combat whenever possible, but the region is crawling with Taliban. We could live with the clashes, but the greatest danger is the improvised explosive devices (IEDs) placed along the roads. In these last weeks, my unit alone found 26 IEDs. A month ago, one of them killed one of our guys. He was from Indiana.” As the shelling slowly stopped, the Americans joined with the Afghan police to set up a temporary checkpoint on the road connecting Tarin Kowt to the countryside and began to stop passing vehicles. The vehicles were being searched for weapons. According to official sources, this year 72,400 Kalashnikov rifles went missing in the south of Afghanistan. Originally, these guns were intended for the government forces but a large portion of them were supposedly sold to the Taliban by the police.