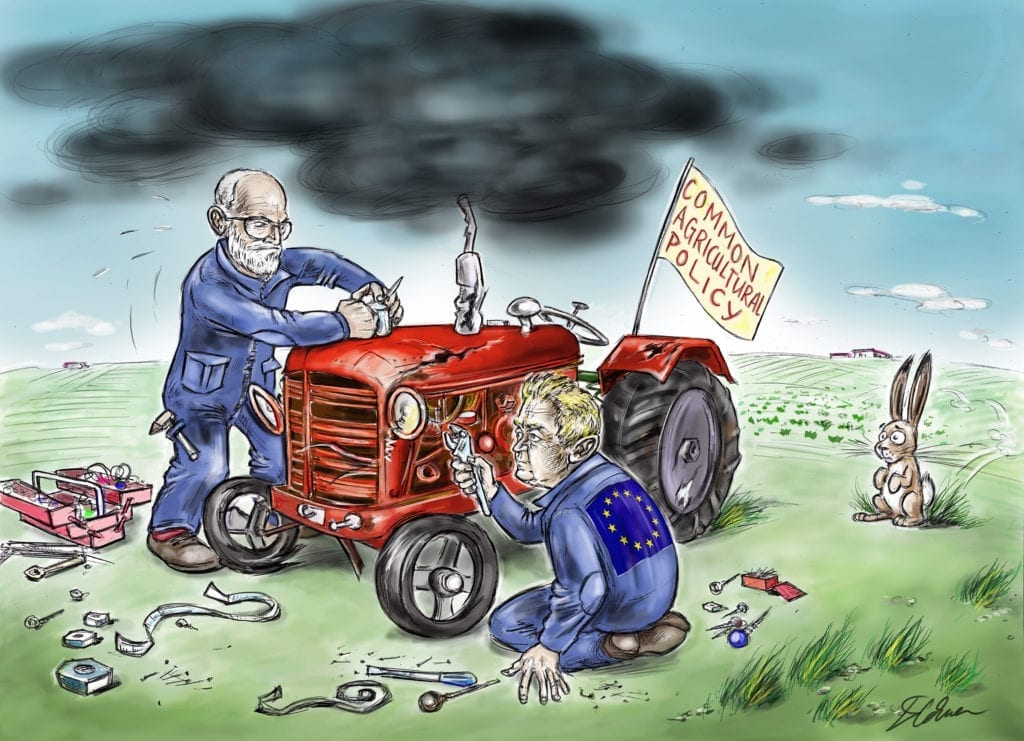

Anything Left to Salvage in the EU’s Farm Policy?

Considering the many blows that our initial hopes for a fairer and greener EU farm policy have received, could the trilogue negotiations and CAP strategic plans still make any difference?

The current reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) started more than four years ago with a large public consultation where over 250,000 citizens (80% of all respondents) asked for an overhaul of the EU farm policy. Long as it may seem, this intricate journey is not quite over yet, as it was just seven months ago that the European Parliament and the Council of the EU defined their positions on the future CAP.

This kick-started the inter-institutional “trilogue” negotiations with the European Commission, which are expected to conclude before the summer, and it will be followed by the final drafting of the national CAP strategic plans, due by the end of this year and which will set out the details of how Member States choose to implement the farming policy until 2027.

Will this make a difference?

Considering the many blows that our initial hopes for a fairer and greener CAP have received during the journey, could these final stages still make any difference? The short answer is that they can but –given some key decisions that have already been made– only to a certain extent. Let’s break this down by focusing on three major environmental features of the farm policy.

Firstly, at the inception of the journey, the European Commission presented an enhanced CAP conditionality, – a set of do-no-harm requirements attached to EU farm subsidies – as the main policy tool to make farming practices more sustainable. Even if the improvements proposed were limited, EU co-legislators did not welcome this approach, arguing that it would impose further rules on farmers.

Accordingly, the co-legislators amended the conditionality proposal, watering it down to just a consolidation of current rules. This change in orientation is largely agreed by now, but CAP trilogues can still give conditionality some credibility by discontinuing the failed CAP greening rules on crop diversification and “ecological focus areas”. Instead, a much better deal must be sought on the new conditionality standards that aim to protect farmland soils and biodiversity.

Eco-schemes

The second feature is eco-schemes, one of the very few novel instruments in the new CAP, designed to work as voluntary incentives for farmers who choose to join them, rather than as additional rules. This has made eco-schemes more politically acceptable over time, and the co-legislators are now looking likely to beef them up significantly, by ring-fencing an EU budget of approximately €9 bn per year to eco-schemes.

With this broad agreement largely behind us, the debate has shifted from quantity to quality. The EU framework for eco-schemes is now likely to be extremely flexible, lacking rules that would ensure Member States implement good eco-schemes that support substantial improvements in farming practices. The biggest risk is that eco-schemes are implemented as a flat-rate payment with little environmental ambition, as many farm unions are currently calling for. This could still be prevented during trilogues by clearly establishing that eco-schemes must include different payment levels, offering attractive rewards in proportion to the efforts made by the farmer.

Connecting CAP and the Green Deal

Thirdly, there is still an utter disconnect between the CAP regulations and the European Green Deal. Unfortunately, the strong legal provisions that would have made this connection effective and enforceable were debated but voted down by the European Parliament last year. Nevertheless, there were a few amendments that survived and explicitly link these two policies on aspects related to data gathering and performance assessments (see items #52 and #53 in our full assessment). These should be preserved preciously during trilogues, even if they are a bare minimum that does not guarantee achieving the targets set for EU agriculture in the Green Deal, such as increasing organic farming to 25% of EU farmland by 2030.

All in all, however, this CAP reform will be remembered by one of its most distinctive and largely uncontested features: the increased autonomy that the EU is giving to Member States to adapt the farming policy to their context and priorities. This model of EU policy-making places great emphasis on the structural debate and exchange between the Commission and the Member States when drafting the national CAP strategic plans, which will detail how CAP funds will be spent in the following years. Only when these plans are revised and approved in 2022 will we be able to assess fully if this is just another failed reform, or if it has sown some positive seeds that could grow in the future into a more environmentally friendly farm policy.