The Global Rush For Greenland

Climate change and geopolitical fever collide on the world’s largest island nation, testing resilience, sovereignty, and Greenland’s place in an increasingly contested Arctic.

During the final hours of the Arctic summer, our small and highly manoeuvrable boat quietly wound its way around variously sized chunks of ice glistening in the sun. “Most of these chunks are between 10,000 and 15,000 years old. The oldest have endured for 250.000 years,” said the boat’s 26-year-old Greenlandic captain Pierre, named after his French grandfather.

The Inuit people, forming around ninety percent of Greenland’s population, know eighty different terms for ice. And indeed, every iceberg and every floating chunk of ice seemed entirely different. The closer we approached the heaps of floating shiny frost, the more alive they seemed. The constant release of ice bubbles kept producing rhythmic noises, making it seem as if the ice was breathing.

“This is ultimate beauty!” I thought while taking in the magnificent surroundings soundtracked by the mentioned white noise.

And yet.

This spring, western Greenland witnessed the break-off of the second largest ice mass in the past fifty years. Now, on these wild Arctic waters, our boat weaved through its remnants, the shattered children of climate change.

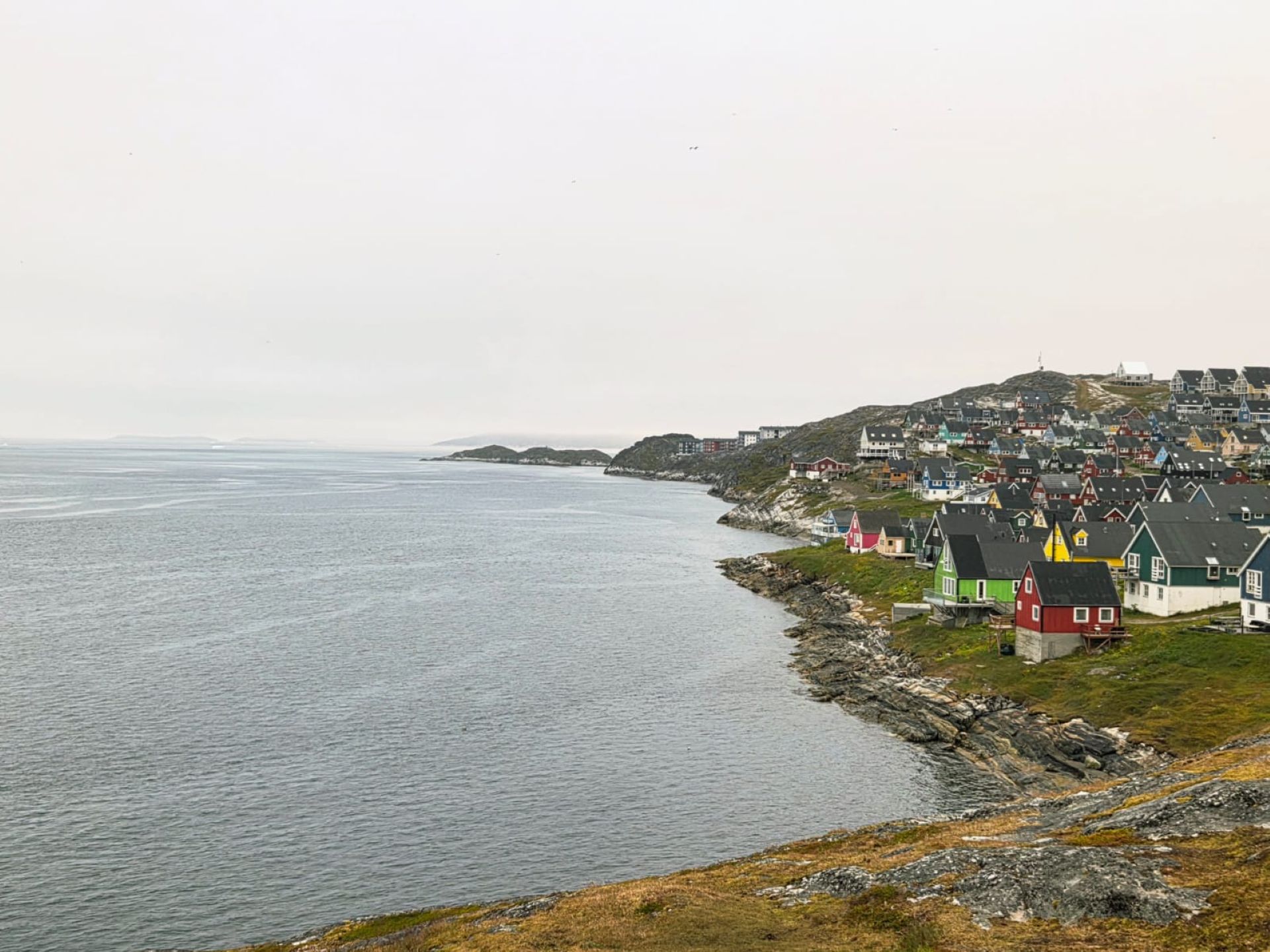

“It’s true that I get to watch this indescribable splendour every day,” Captain Pierre remarked as we neared the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk. “But I honestly can’t say it makes me happy. Why? Because I know what the melting of the ice means.”

On 27 August 2025, Denmark summoned the American charge d’affaires and demanded answers concerning a highly delicate case of alleged US meddling into Danish and Greenlandic politics.

At least four American citizens – all reportedly with close ties to President Donald Trump, according to the public-service Danish Broadcasting Corporation – were alleged to have spent weeks in Nuuk collecting potentially harmful information on Denmark. They were also claimed to have been forming a list of local leaders who could be enlisted to the cause of the American takeover of Greenland. Their supposed activities were discovered by the Danish Security and Intelligence service.

If true, my Danish and Greenlandic sources view this sort of involvement as a reconnaissance mission, with the added goal of widening the rift between Denmark and Greenland.

Greenland, an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, gained home rule in 1979 and self-government in 2009. While remaining part of the Danish Realm, it has long balanced its growing autonomy with economic dependence on Copenhagen.

After the story broke, the Danish Minister of Foreign Affairs Lars Løkke Rasmussen stated that every form of interference into the kingdom’s internal affairs was completely unacceptable. Aaja Chemnitz, a member of the Danish parliament, told the reporters: “Such attempts at infiltration into the Greenlandic society are unacceptable. It is for the inhabitants of Greenland to decide what sort of the future they want.”

Like the rest of the Arctic, Greenland is located at the very core of the global conflict for natural resources and geopolitical control.

The rumour that Trump’s men were doing the rounds across Greenland started as far back as spring. In May 2025, the Danish public was outraged upon learning of the White House’s plans for a Compact of Free Association (COFA) – a defence and economic agreement that grants the U.S. special strategic rights – with Greenland. Under this arrangement, American access to the Arctic island would expand significantly, in exchange for visa-free travel and U.S. support for Greenland’s defence. The United States has already made similar agreements with several Pacific nations.

President Trump also decided to reassign the American soldiers situated at the Greenlandic military base from the U.S. European command to the U.S. Northern command.

This is not mere ‘aggressive rhetoric’. This is a clear call for tectonic change.

According to Jeppe Strandsbjerg, a professor at the University of Greenland and an expert in Arctic security, with whom I spoke in a popular caffe at the outskirts of Nuuk, the words spoken and actions taken by the American president were perceived as a form of pressure and even blackmail. This is the prevalent view both in Greenland and in Denmark.

It bears mentioning that the American pressure has been mounting since 2021, when the US decided it wanted to significantly enhance its security-intelligence infrastructure across the world’s largest island. Yell all attempts at making this a reality were thus far met with firm opposition from the Greenlandic government.

“The Russian attack on Ukraine changed a lot of things,” professor Strandsbjerg relates. “Nowadays, a lot more Danish soldiers can be seen in Greenland. And a whole lot more of military exercises. The changes are actually quite dramatic, and growing more dramatic by the month.”

Strandsbjerg is convinced that the political tension created by Trump’s statements and the local parliamentary election have by now mostly simmered down. At least temporarily. “No one here wants any form of escalation,” he was emphatic. “All of us want peace in the Arctic.”

He also points out a civilian-protection program initiated in Greenland over the past few months. Among other things, the program enables the local youths to learn military skills. The project proved very popular. So popular that Strandsbjerg believes it could prove an important step in securing a greater level of autonomy.

Despite the White House’s ambitions, this spring saw Denmark sign an agreement on military cooperation with the United States – which, ironically, involves the deployment of a greater number of American soldiers to Greenland. The US has always viewed the island as a shield against Russian nuclear missiles.

“Greenland is not so hard to defend. There are relatively few points to defend, and we of course have a plan for that. NATO has a plan,” stated Soren Anderson, the Commanding Officer of the Danish Joint Arctic Command. “We are cooperating with the United States, just like we always have.”

A turn toward the EU?

The initial responses to Trump’s announcement were mixed and at times even confused. On the one side, the capital of Greenland Nuuk saw protests against the new American colonialism, but there was also open support for the takeover.

According to Jeppe Strandsbjerg, Greenland has recently seen an increased willingness to cooperate with Denmark and the European Union – but also with the United States and Canada, which are geographically closer to Greenland. Strandsbjerg believes the said increase was caused by the wish for Greenland to be recognised as an equal partner.

“Throughout history, Greenland has strategically leaned more toward the United States,” he explains. “And America, for its part, viewed Greenland as a part of its defence ever since the fifties. After the end of the cold war, things calmed down for a bit. The American focus was on other matters – Afghanistan, the Middle East … And now the situation has changed.”

Strandsbjerg also speaks about the major wave of discomfort that swept over Greenland after the Russian annexation of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s statement at the Russian Arctic Forum in 2025 that the Arctic represented a Russian geopolitical priority. China has also revealed an ever-mounting appetite for expansion into the Arctic region. 2019, the local geopolitical and security environment underwent a dramatic change. One also needs to figure in the consequences of climate change enhancing and multiplying all the other threats and problems.

The fact is that Greenland lies at the very heart of climate change – or, if you prefer, at its epicentre.

At the beginning of 2025 Denmark invested over two billion Euros into bolstering its Arctic defensive capabilities – including new military ships, long-range drones and additional satellite cover. France has also made an offer to station its own soldiers in Greenland. The European Union seems to entertain similar ideas.

“But you shouldn’t forget,” Professor Strandsbjerg reminds me, “that after the referendum in 1985, Greenland was the first to leave what was then still the European Community. It was the original Grexit!”

Putting jokes aside, he continues to explain that The EU remains deeply important to Greenland. Both economically and in areas like education. Much of that cooperation happens quietly, “under the radar,” as he puts it.

While North America may be geographically closer, Strangsbjerg sees a new openness and warmth in Greenland’s recent dealings with the Europe. The EU’s decision to open an office in Nuuk is a clear sign of that shift. “The dialogue is growing stronger,” he says. “Though it is of course clear that the EU has its own interests here – a lot of them having to do with critical minerals.”

In May 2025, Greenland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Vivian Motzfeldt visited Brussels, to announce that Greenland wished to strengthen its ties with the European Union, as reported by Reuters. She stated that the relationship should become more visible and highlighted the development of Greenland’s critical mineral industry as a key area for cooperation.

So, what does all the above mean for Denmark?

“Well, Denmark seems to have sobered up a bit over the last few months,” Strandsbjerg explains. “Donald Trump appears to have actually brought Greenland and Denmark closer together. Which of course doesn’t mean we should simply forget all our existing problems. A part of Danish media still depicts Greenland in a very insulting light. Which probably has something to do with some quarters still not being ready to face the colonial past.”

Indecent proposals

Donald Trump is not the first American president to desire the purchase of Greenland. In 1946, Harry S. Truman offered Denmark a sum corresponding to today’s billion dollars. But the offer fell on deaf ears.

Jeppe Strandsbjerg has no fear that Greenland will fall for any form of “indecent proposal” from abroad – be it from North America, Europe, Russia or China. Still, he acknowledges that a new phase of interest in Greenland’s natural resources and strategic position appears to be unfolding, with parts of it already underway.

Yet Strandsbjerg remains confident in Greenland’s resilience. “Our politicians have no difficulties making tough choices,” he says. “Especially when they’re trying to protect what is deemed essential, meaning Greenland’s natural bounty and our way of life.”

He points to the ban on uranium mining as a defining example of that resolve. “Just remember our parliament’s decision to ban uranium mining!” he says. It was only the second law passed by Greenland’s parliament after gaining autonomy in 2009 – one that focused on protecting natural resources and ensuring that foreign companies paid fairly for the right to use them.

All of Greenland’s political parties are in favour of complete independence from Denmark.

Professor Strandsbjerg argues that the real question is not whether Greenland should be independent, but what kind of independence it actually wants. “In my opinion, we should be talking statehood – but not necessarily in the sense of 100-percent sovereignty. The relation should be country to country, but with extra cooperation and partnership.”

Greenland, he says, should certainly have the right to decide its own constitutional future. But a simple declaration of independence, he warns, would mean little without first dismantling the hierarchical relationship that still defines its ties with Denmark. The island continues to rely heavily on Danish funding, and around 20,000 Greenlanders live in Denmark – links that make a clean break both difficult and undesirable.

“What is needed most of all,” Strandsbjerg concludes, “is open, continuous dialogue.”

A tourist explosion

On November 28 2025; a new international airport opened in Nuuk, greatly improving Greenland’s connectivity with the rest of the world – particularly with North America and Denmark.

“We were ready for the opening of the airport,” Casper Frank Møller, the CEO and co-founder of the Raw Arctic tourist agency, tells me. “We had a lot riding on the project”

I meet the 28-year-old entrepreneur in his office on the outskirts of the Greenland capital, where the windows look out over a spectacular view of the mountains and the Arctic sea.

“At first,” he recalls, “Trump’s rhetoric made us fear that people would stop coming. But our worries turned out to be completely unfounded. If anything, Greenland became more attractive than ever.”

Tourism, he says, had surged beyond anyone’s expectations. “We’re just coming out of a crazy summer,” he laughs. “Last year, when we started Raw Arctic, there were only three of us. Now there are twenty-one – and the profits have followed the same curve. We’re working non-stop. What we’re seeing is nothing short of a tourist explosion.”

In 2024, Greenland was visited by some 150,000 tourists according to figures from Visit Greenland, the country’s official tourism organisation. The number is expected to double in 2025. Yet at the end of August, the local tourism was disrupted when, due to insufficient security measures, Denmark decided to temporarily ban all international flights to and from the Nuuk airport.

The ban was imposed on the day when the spying scandal broke. My local sources remain convinced the two stories were heavily related.

The Raw Arctic agency specialises in guided tours – most of them of Nuuk’s surroundings, where the globe’s second large fjord-system is located. The array of offered activities ranges from kayaking and fishing to observing melting glaciers and travelling with dog sleds. Møller’s team is focused on authenticity, on presenting the visitors with the Greenlandic way of life. The principle of quality above quantity means the company only accepts a limited number of customers.

“We are not driven by greed,” Møller assures me. “An old Greenlandic proverb says that you don’t need money to survive, you need knowledge. You need lore. We got plenty. Most Greenlanders do. We are among the last of the hunter-gatherers. We don’t buy our meat and fish in shops. We provide it ourselves. If we didn’t nurture our traditional skills, the nature here would wipe us out in a heartbeat.”

That self-reliance, he explains, naturally shapes how Greenlanders think about sustainability. “Our instinct is to go as sustainable as possible. “If I could, I would immediately ban all cruise ships operations as they are now. More focused on increasing economic profits for the locals in Greenland.”

Though Casper Frank Møller’s familial ties run both to Greenland and to Denmark, Greenland remains his homeland – the land where he grew up and where he intends to stay.

“I can only dream of a paradigm-shift,” he says. “I can only hope that sustainable tourism will someday replace fishing as our primary source of income.”

Fishing, Møller tells me, remains a core part of Greenlandic identity, but it also inflicts enormous damage on the environment.

A few months ago, Møller, who also lectures economics at the Nuuk university, asked his students to come up with their own business plans. All twenty of his students presented him with a plan based on fishing.

“I can hardly describe my horror,” he recalls. “I mean, these were all Greenland’s future businessmen and politicians! So, I took my time to explain in detail how destructive mass fishing is to the oceans, for entire ecosystems. I threw all their plans in the bin and instructed them to make new, sustainable ones.”

He smiles. “And they did. Some of them actually came up with pretty nifty ideas. It was the most important thing I did in my life!”

Despite being a country of just 59,000 people spread across an area roughly a third the size of the United States, Greenland stands on the front line of climate change.

According to the latest data from NASA, the average temperature of the sea around Greenland has already risen by two degrees Celsius over the last decade. Since 1979, the quantity of sea ice in the Arctic was reduced by half. The same period saw the melting of two thirds of the summer ice with a combined weight of 14 billion tons.

If all Greenlandic glaciers were to melt, the global ocean levels would rise by three meters. The melting of all Arctic ice would entail the oceans to rise by seven meters. The scientific community is convinced that all of the Arctic will vanish by the end of the current century. A quarter of the Arctic area is covered with permafrost, which is now melting so fast we should probably start reconsidering the term.

Under Greenland’s fast-melting ice are located as many as 39 of the 50 minerals deemed ‘critical’ by the United States and a part of the European Union. According to the U.S. Geological Survey data, Greenland holds about 18 billion dollars’ worth of oil and earth-gas reserves. For the time being, the fossil-fuel corporations have decided drilling would prove too expensive. Any such venture would also have to face heavy opposition from the Greenlandic authorities. Yet all this could change at any time.

In Møller’s view, the worst possible scenario would be the takeover of Greenland by the huge global mining corporations. He is sharply opposed to opening new mines and exploiting the island’s natural resources. “When we’re talking economic development, we must first determine its price,” He argues. “There are very few of us, and we are not exactly versed in heavy industry – which are two additional reasons why Greenland should be closed to the exploiters.”

It also worth noting that the melting glaciers recently opened two new Arctic trade routes – the so-called Northwest passage and the Transpolar Sea Route. Between 2013 and 2023, the volume of merchant naval traffic in the Arctic rose by 37 percent.

The Northwest Passage remains a challenging corridor. The Dutch freight ship, Thamesbourg, en route from China, ran aground in the Franklin Strait, and spent 33 days stranded in the ice before being refloated on 9th October 2025 according to CBC news.

Still, the shorter transit distance makes the risks worthwhile for many shipping companies. The Arctic route cuts nearly 4,000 nautical miles compared to using the Panama Canal. Being able to control these emerging trade routes is one reason the United States is so eager to expand its strategic and economic presence in Greenland.

“Donald Trump is playing a predictable game,” Møller expresses. “All he cares about is profit. We shouldn’t fall into his trap. We must not respond to aggression with aggression. So we must do everything in our power to defuse the tensions.”

He noted that few Greenlanders wish to join the United States, and that independence remains the ultimate goal. But he cautions, the financial realities cannot be ignored. “Every year, Denmark provides us with around 900 million euros – more than forty percent of our entire budget. These funds sustain our welfare state. Where are we to find the money if we strike off on our own? We need to plan for the long term.”

According to Møller, Greenlanders value cultural independence above all else. But he worries that the country is becoming increasingly divided. “You have to understand,” he says, “many people here have close ties to Denmark. The strongest calls for independence come from the small coastal settlements, far from Nuuk. Over there, life is incomparably harder. And the bonuses provided by the welfare state are much smaller.

Prologue for the future

Møller takes great care to adapt his work to the mounting realities of climate change. “This spring, the largest chunk of ice in fifty years – and the second largest ever broke off just seven kilometres from where we’re sitting,” he recalls. “The cracking sounds were so loud they still reverberate in my heard. The sea was filled with floating ice, and it still is. It was terrifying. A number of settlements were cut off from the world.”

He pauses, then adds, “I see that event as a prologue for the future. We need to prepare for any eventuality. I can feel seasons merge into one another, and I can see the changes in the plants and animals. A huge shift for the worse is coming. It’s inevitable.”

“This is why we need to step together and live as sustainably as possible,” Møller says. “Our guiding principle should be solidarity.”

That spirit of solidarity, however, seems increasingly absent from the zeitgeist of modern Greenland. “The American way – the way now being forced upon us – is the furthest removed from what we actually need”.

Still, Møller remains hopeful. He believes Greenlanders will stay true to their values of sustainability and self-reliance, rejecting outside pressures and caring for their natural environment. “Greenlanders are natural guides by … Well, by nature! Around here, if you don’t have your own boat, sled, dogs and hunting knowledge, you are finished!”

An exceptionally egalitarian people

In 2023, Robert Christian Thomsen, a professor at the Aalborg University, Denmark, wrote that Greenland was on the path of becoming the first Inuit country to gain full independence. His view was that Denmark was undergoing a process of full decolonialisation.

I talked with him to challenge his basis thesis by posing a question: “Isn’t the American attempt to purchase Greenland a new form of colonialism?”

“Well, that seems to be the question for Greenland!” he replies. “Even a year ago, the majority of Greenlanders and all the political parties championed independence, feeling it should be achieved as soon as possible, no matter the cost.”

But the recent surge in American interest has, perhaps unintentionally, made many Greenlanders more cautious about what independence might really mean. “Before, colonialism was understood exclusively in terms of the relations between Greenland and Denmark,” he explains. “Now this is no longer the case.”

The Danish professor and Arctic socio-cultural researcher continues: “The real possibility of Greenland falling under the American sway has changed a lot of hearts and minds. Suddenly, many are no longer in a rush. The polls show that we prefer remaining with the devil we know. Even while realising that Danish colonialisation wasn’t beneficial to Greenland. If anything, it was the opposite.”

In a recent poll, 85 percent of Greenlanders stated they did not want to fall under the American sphere of influence, while 84 percent were in favour of immediate independence from Denmark. Behind that tension lies a shared dream: every Greenlander I talked to said they hoped to one day see their red-and-white flag flying outside the United Nations headquarters in New York.

“Yes, Greenland was colonised,” Professor Thomsen nods. “Yes, Denmark is a colonial country. But Greenland was colonised inside a socio-political model which partly rhymes with Greenlandic values.”

Professor Thomsen explains that Greenlanders are an exceptionally egalitarian people. The 2025 Greenlandic general election was the first time that a social-liberal party won more votes than the socialist and social democratic parties. Yet the public sector continues to dominate Greenland’s economy, with autonomous authorities playing a leading role, while the private sector remains small. Public ownership is highly valued and the local welfare state is modelled closely on Denmark’s.

“Greenland,” Thomsen says with a smile, “is about as out of sync with the American neoliberal doctrine as you can possibly get.”

In his view, the path to independence will be difficult, and therefore needs to be gradual. “Greenlanders can see how the U.S. treats Inuits, how badly they are doing over there. So, as we already said, they prefer the devil they know. Even Greenland’s far-right party is not in favour of the American takeover.”

He also points out that Donald Trump first announced the intention to purchase Greenland during his first term in office. “Back then, Greenlanders only laughed. They are no longer laughing now.”

According to Thomsen, this is part of the reason why, in Danish eyes, the European Union has recently grown in popularity. “Inadvertently, Trump brought Denmark and Brussels much closer than they used to be. He is the main reason why the EU is once again ‘big’ in Copenhagen.”

Still, none of this diminishes Greenland’s long-standing desire for independence – a goal with firm legal precedent. The Self-Government Act of 2009 granted the Inuit population the utmost capacity for self-determination. In theory, they could declare independence tomorrow. Since 2009, the Greenlandic parliament is fully in charge of the island’s taxes, healthcare, fishing, education, agriculture, housing policies, and – and crucially – natural resources. The defence and the foreign policy remain the prerogative of Denmark.

Yet for independence to be viable, Greenland must first strengthen its economy. Under the Self-Government Act, the island can only assume full control when the country is financially self-sufficient. The public sector, which makes up roughly half of Greenland’s GDP, remains heavily reliant on Danish funding. Out of an annual budget of 14 billion Danish kroner (just under two billion euros), 5.6 billion kroner comes directly from Denmark.

The rest depends largely on fishing, which accounts for 95 percent of Greenlandic exports – leaving the economy exposed to the dangerous combination of fluctuation in global seafood prices and the impacts of climate change.

Even so, most Greenlanders remain firmly in favour of independence. But only, as polls suggest, so long as their current welfare system and living standards are not threatened.

“Once economic independence is achieved,” Thomsen explains, “its political counterpart will not be very far behind.”

Robert Christian Thomsen has been teaching Arctic studies in Denmark for the past thirteen years. But it was only in the last months that he was able to detect any sincere interest in Greenland by the Danish media and by the Danish society. Much the same can be said for the Arctic as well.

“Over here, Greenland was only rarely even a topic of public debate,” he recounts. “We really don’t know very much about it. A huge problem is that in school, the Danish children hear virtually nothing about Greenland.”

He explains that he didn’t learn anything about Greenland until university. However, this is changing. “A few days ago, my youngest son told me his class would spend the next two days learning about Greenland. This comes with a great delay, yet it is nonetheless a revolutionary development!”

Like most of the people I talked to, Thomsen believes that Denmark’s relation to Greenland was largely based on ignorance. “The Danes simply don’t care about Greenland. They see it as an exotic land of ice and polar bears. What it actually is, and who Greenlanders are, interests almost nobody.”

Yet the reality may be even worse. It has long been Thomsen’s observation that the people of Denmark see themselves as ‘the best colonisers in history’. At least parts of Danish society thus hold the opinion that the Greenlanders should really be thankful.

But history tell a different society. In August 2025, Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen travelled to Greenland to issue a formal apology for the forced contraception of thousands of Inuit women during the 1960s and 1970s – a policy that caused deep trauma and lasting mistrust. Greenland did not take full control of its own healthcare system until 1992, and, according to BBC reporting, some cases of forced contraception may have continued as late as 2018.

“The fact that the Danish colonial rule was a racist, degrading and thoroughly hierarchical one has been repressed, if not outrightly denied,” professor Thomsen states. “Yet colonial skeletons keep falling out of Danish wardrobes.”

A racist parenthood test

The same month that Denmark’s Prime Minister apologised for decades of forced contraception, Ivana Nikoline Brønlund, a member of Greenland’s handball national squad, gave birth to daughter Aviaja-Luuna, on August 11, 2025, at the Hvidovre hospital near Copenhagen. Just an hour after delivery the Danish authorities seized the newborn, claiming Brønlund had failed to perform a ‘parental competence’ check.

For years, this deeply discriminatory test had been imposed on parents of Greenlandic origin. Although the test was officially banned earlier this year, with the law coming into effect in May, Brønlund had been tested in April – just weeks before the ban. Her baby was taken from her arms and placed in foster care, with “parental trauma” cited as the reason.

Protests erupted in Nuuk, with many painful memories brought to the fore. There was no doubt that the authorities’ actions were illegal. Indeed, the Danish Social Appeals Board ruled on September 22 2025 that the decision to forcibly remove Brønlund’s child was based, as reported by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, on an incorrect basis.

However, by then, more than 6 weeks had passed and the damage, both emotional and symbolic had already been done.

Many in Greenland were reminded of the case from 1951, when the Danish authorities transported 22 Inuit children to Denmark to turn them into ‘civilised citizens’. Their parents had given consent, but only after being misled and denied full information about what was really happening. The uprooted children were meant to return to Greenland as enlightened, cultured and civilised citizens – who would help transform it into a modern society.

On a sun-kissed Arctic day at a café in downtown Nuuk, I meet with Najannguaq Hegelund, who specialises in legal representation of parents whose children were taken by the Danish authorities on account of the competency test. She has spent a long time fighting the systemic racism and Danish colonial attitudes she experienced herself while studying in Denmark.

“I started volunteering because I was interested why they took the children. What was behind it?” Hegelund tells me. “I used to believe that the parents must have done something truly awful in order for that to happen. Something like abuse, violence or neglect. But the more research I did, the clearer it became that this was not the case. So I decided to help the parents in their legal struggles.”

Over the last seven years, she has represented several dozen Greenlandic families stripped of their children. In her view, the Danish perspective on the Inuit population failed to do much evolving with the passage of time. Even among the highly educated circles, the perspective is still largely based on stereotypes and clichés based around alcoholism and general backwardness.

“The whole thing is based on a cultural misunderstanding, so to speak,” the mother of three explains. “The Danish authorities refused to understand that Greenlanders have their own approach to childcare. Just like we have our own way of life. They tried to impose their own formula of structure, order and discipline.”

Denmark and Greenland, she describes, are two completely different worlds. “Our cruel climate has long forced us to learn to live from day to day. We are used to always adapting to the circumstances,” she says. “We don’t like to do too much planning for the future. When the weather is clement, we simply seize the day!”

Hegelund also points out that the intelligence and parenting tests used by Danish authorities were culturally biased. “In truth,” she tells me, “they were completely inappropriate, given that they were based on everything Danish and ignored everything Greenlandic.”

Najannguaq Hegelund is nonetheless convinced that the relations between Denmark and Greenland have changed for the better over the last few years. The Greenlanders became more confident in themselves and their rights, and have started to put more pressure on Denmark. “What we’re demanding from Copenhagen is equality, especially with regard to employment opportunities and the functioning of the public healthcare system.”

But deep inequalities remain. Healthcare and education in Greenland still lag far behind Danish standards. Hegelund explains there are not enough teaches in Greenland, so many high-school classes are mostly conducted in Danish. As a result, many children drop out of school.

“It’s simply unacceptable,” she says. “All this is closely connected with our high rate of suicide, especially among young men.”

Indeed, Greenland continues to suffer one of the highest suicide rates in the world. Research published in 2023 in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health shows that, while the numbers have fallen slightly, the suicide rate remains alarmingly high – averaging 81.3 deaths per 100,000 people between 2015 and 2018 – six to seven times higher than in neighbouring Nordic countries.

Colonial reproduction

Hegelund explains that she returned to Greenland three years ago after living in Denmark, a place where she never truly felt at home. Language was a big part of it. She often felt that people saw her uneducated or inferior. She describes this a common perspective shared by many Greenlanders.

“Greenlanders have grown weary of all that we spoke about,” Hegelund says. “Our language is the only language of the Arctic peoples, and one of the few surviving native languages. It is fluently spoken by 80 percent of Greenlanders. It is very important to us to have managed to hold on to our culture and our way of life in spite of all the obstacles placed in our path. The ever so nationalistic Denmark should respect that, shouldn’t it?”

In Denmark, the prevailing narrative still portrays the colonisation of Greenland as a “soft” process – non-violent and even beneficial to the Inuit population. Hegelund bristles at the idea, “Violence is violence. Pain is pain. And that’s all that needs to be said on the matter. Violence is not only physical, but that violence shows it self in many different ways, such as psychological violence, and that violence is violence”.

A telling sign of the enduring legacy of colonialism, she noted, is that many Danes still occupy senior positions both in Greenland’s government and in key public companies.

In the long run, Hegelund supports Greenland’s independence – but she is increasingly concerned about the mounting geopolitical interests and the rapid effects of climate change. In her view, climate change has already severely disrupted the traditional Inuit hunter-gatherer way of life, causing it to slowly melt away – much like the ice that once defined it.

In the early evening hours, as we weave our way through the fractured remains of Greenlandic glaciers, the weather suddenly shifts.

Dark clouds envelope us and a fierce wind begins blowing from the East. The gulls overhead shriek louder, their cries intensifying. The Arctic Sea darkens and grows restless, rolling in waves strong enough to rock the boat. The surrounding ice sways in unison – it is a haunting yet beautiful set to behold.