Kashmir Calling: A Wedding Under Curfew

It is mid week, the middle of the day and the streets of Srinagar are deserted. It could be 3:00 in the morning when only the occasional person is seen and the odd shop open. For five months in 2010 it was like this four out of every six days. The Quit Kashmir Movement and All Parties Hurriyat Conference call for a hartal (strike) to demand azadi (freedom) and the Indian military responds by imposing a curfew to prevent the Kashmiris from demonstrating. Road blocks are put in place, military vehicles move into strategic positions and troops go on patrol.

The violence in 2010 claimed an estimated 112 Kashmiri lives when the Indian Army sparked the unrest by shooting at unarmed demonstrators on June 11. This violence has occurred most often when the Kashmiris challenge the curfew, swarming to junctions and the major arteries of Srinagar, with young men – and women – throwing projectiles, chanting slogans and, in general, resisting India’s occupation. Curiously, the slogans painted and chalked on roads, walls, shop shutters and in the grime of car windows are mostly in English: “Freedom”, “Go India Go Back”, and “Go Indian Dogs”.

The Indian Army is predominantly made up of Hindi speakers, with little Kashmiri known, certainly not the alphabet. Kashmiris are conversant in Hindi but lack literacy skills, so the default language of both sides – and useful for international media attention – is that of the former colonizer, Great Britain. Indeed, Britain is responsible for laying the seeds that grew into the current crisis in Kashmir.

The main issue was who would control the main artery leading into Central Asia.

Ernest Bevin

During its occupation of India and following the first Sikh War of 1845-46, Britain was struggling to administer the remote territory of Kashmir. The Raja of the Jammu region adjacent to south-east of Kashmir and Prime Minister Gulab Singh of the Sikh government in Lahore, present-day Pakistan, had refused to side with the Sikhs. As a solution, the British rewarded Gulab Singh, an upper caste Hindu and ethnic Dogra, by appointing him Maharajah of Kashmir and selling the Valley of Kashmir for 7,500,000 Rupees at the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846. In exchange the British retained supreme control of the Valley.

A hundred years later, Britain was instrumental in the Partition of Pakistan and India. Subsequently Pakistan invaded and occupied Kashmir in October 1947 and Britain lobbied at the United Nations in favor of Kashmir becoming a Pakistani province. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin told US Secretary of State George Marshall that “the main issue was who would control the main artery leading into Central Asia.” The Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton stated that, Pakistan was central to Bevin’s ambition to organize “the middle of the planet.”

On the two days when there is no strikes or curfew, Srinagar turns into a mad house, with people trying to pack a week’s business into 48 hours and families stock-piling food for the inevitable next shutdown. At that time, this was the Kashmiri status quo. In the midst of all this a wedding was to take place, but the guest list was to prove rather unpredictable and the ongoing situation generating a rather somber tone to the celebrations.

Gilani is On Board

I had been to Kashmir before in slightly more ‘normal’ times; at least there were no curfews. While there were some tourists, they were not on the scale of the 1970s and early 1980s. Kashmiris I had met in Srinagar on my first visit had family members in New Delhi that I later befriended and stayed with on return visits. It was this extended family, which shall go under the pseudonym of Manzar due to the very valid fear of repercussions from the Indian authorities given their opinions on the occupation, who invited me to the wedding of one of their daughters.

Flying to the Vale of Kashmir was a better option than enduring again a 24-hour, 1,000 kilometer bus journey between New Delhi and Srinagar. One of my fellow travellers was Sayyed Ali Shah Gilani, Chairman of the Hurriyat Conference (HC). He was warmly greeted by the Kashmiris waiting at the departure gate with handshakes and smiles all around. Gilani was clearly admired for his decades-long game of cat-and-mouse with the Indian government and his calls for hartals and demands for hurriyat (freedom).

On arrival in Srinagar, Gilani was detained by the authorities and later placed under house arrest, contributing to some 140 days spent in the confinements of his property during 2010, along with 40 days of imprisonment under India’s Public Safety Act. One of the Manzar’s commented: “It is a part of daily life for him, like having a cup of chai (tea).”

As a foreigner, I had to register at the airport with Indian intelligence plainclothes man, and while being greeted by the Manzars, was questioned by a Kashmiri tourist policeman in a disheveled uniform, who took down my particulars as “Mr. Paul from Ireland.” It was a quick drive through the empty streets of Srinagar to the Manzar’s three-story home near Lake Dal. I related to them that Gilani had been on the plane, but for reasons indicative of the sectarianism that is as plentiful in Kashmir as in the rest of India this aroused little curiosity.

This is not the Muslim-Hindu fitna (discord) that has flared off-and-on in Indian politics since the 1947 Partition with Pakistan. A recent controversial government paper has shown that Muslims are under-represented, and politically and socially disadvantaged in India. In Kashmir, one million Hindu Pandits were forced out over the years due to religious extremism and the perception that they sided with the predominantly Hindu national government rather than with Kashmir.

While this is a lingering scar, contemporary Kashmiri sectarianism is between the majority Sunni population and the Shia, the latter only having marginal political representation in the Hurriyat Conference (HC). It is a similar story for minority Shia in other Islamic countries, such as neighbouring Pakistan, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, and an issue in countries where the Shia are in the ascendancy, namely Bahrain and Lebanon.

“I don’t like Gilani,” said Reza, the brother of the bride-to-be. “Gilani hates Shias.” This is not to insinuate that the Manzars dislike Sunnis – indeed, Reza is engaged to a Sunni and one of his father’s best friends is a Sunni – rather the Shia feel discriminated against by Gilani and other sectarian leaders. Division has become a hindrance for the Kashmiri resistance, as it has with every other occupied people, such as the Palestinians, when the occupying and neighboring powers successfully drive a wedge between, and pit the locals against, each other.

The extent to which this occurred was highlighted in January 2011 by the chief spokesman of the HC, Abdul Ghani Bat. At a Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) seminar he spoke out against the murders of Kashmiri intellectuals by “unidentified gunmen”, notably Mirwaiz Mohammad Farooq, father of Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the current chairman of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, killed in 1990; Abdul Ghani Lone, lawyer and politician, killed in 2002; and Professor Abdul Ahad Wani, JKLF ideologue, killed in 1993.

“Lone Sahib, Mirwaiz Farooq and Professor Wani were not killed by the (Indian) army or the police. They were targeted by our own people,” said Ghani Bat. “The story is a long one, but we have to tell the truth. If you want to free the people of Kashmir from sentimentalism bordering on insanity, you have to speak the truth… Here I am letting it out. The present movement against India was started by us killing our intellectuals… wherever we found an intellectual, we ended up killing him.”

Internal Kashmiri rifts have been exacerbated by Pakistan’s notorious Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) sponsorship of militant groups and bank-rolled by the House of Saud spending over $50 billion globally in the past decades… ever keen to export its version of Islam – Wahhabism. Pakistan, supported financially by the unlikely trio of China, Saudi Arabia and the United States, has backed Kashmiri militant groups for over 30 years. Former Pakistani President, Pervez Musharraf, admitted in October 2010 in London that the ISI set up such groups in the 1980s and early 1990s to attack India. As former Indian Ambassador Narendra Sarila said, “many of the roots of Islamic terrorism sweeping the world today lie buried in the Partition of India.”

AZADI

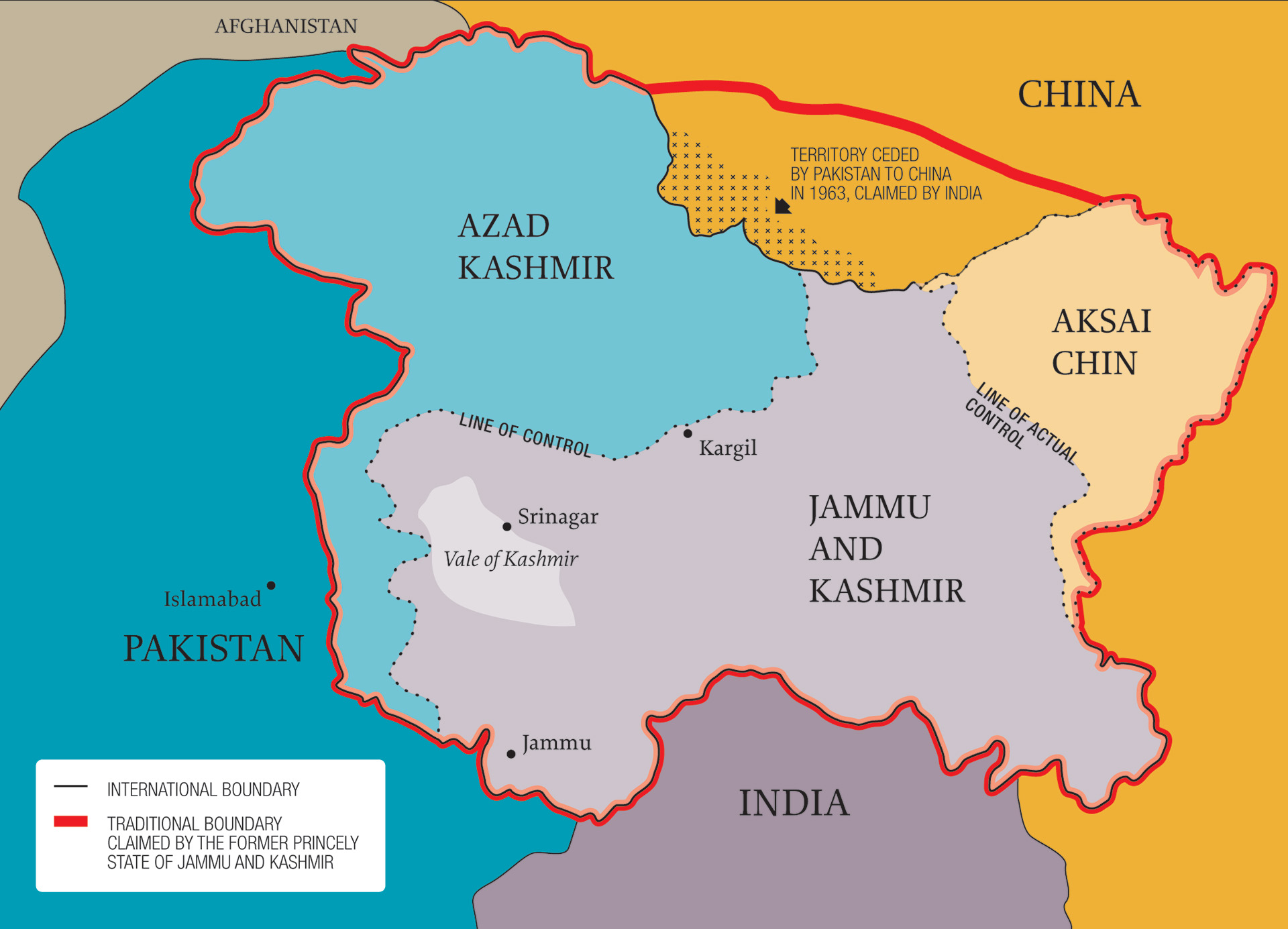

In 1989, a popular rebellion – a Kashmiri intifada – against Indian misrule began, further stoked by militant Islamic groups connected to the ISI in the wake of the end of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan which sent scores of Afghan veterans and Pakistani Kashmiris across the Line of Control (LoC) that separates Indian Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), and the Pakistani Azad (free) Kashmir (China has the remaining 20 percent called Aksai Chin, which is claimed by India). This proxy war between Pakistan and India, that remnant of the 1947 Partition, put the Kashmiri populace in the middle. Intifada after intifada has occurred since 1989 and the Indian Army has cracked down hard, notably in 2001, when over 1,000 civilians were killed. Over 45,000 Kashmiris have been killed since 1989.

In August, 2011, 2,156 bullet-riddled bodies were found in unmarked graves across Kashmir following a three-year investigation by the Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission. According to the report the bodies were of unidentified militants, but 574 were identified as civilians. “There is every probability that these unidentified dead bodies buried in various unmarked graves at 38 places of North Kashmir may contain the dead bodies of enforced disappearances,” the report said.

Thousands of people have disappeared in Kashmir over the past two decades, predominantly young men. Some joined militant groups and were killed in action. Others were killed or detained by the Indian authorities, leaving wives and families in an agonizing limbo as to whether their men are still incarcerated or dead.

One major difference in 2010 from former crises, when feelings rose to a boiling point and Kashmiris took to the streets, is that this time there was minimal militancy – apart from the stone-throwing and rioting. Sympathy with the militants has waned – particularly for Pakistani-backed groups – but anger with New Delhi’s political dillydallying and iron fist policy in tackling the “Kashmir issue” has augmented. The youth are not interested in siding with New Delhi or Islamabad. The youth want independence, or, at least, more autonomy from India.

India champions itself at ‘the world’s largest democracy’ so it would be fitting to call for a referendum on what the

Kashmiri people really want.

A poll released in May 2010, carried out by Chatham House on both sides of the LoC, affirms that just 2 percent of respondents in J&K want to join Pakistan, and only 28 percent want to join India. More than four in 10, or 43 percent of the total adult population, want independence, particularly in the Kashmir Valley Division (between 75 and 95 percent), and 82 percent of those polled in Srinagar (in Jammu just 1 percent, Leh 30 percent and Kargil 20 percent). Some 44 percent of Pakistani Kashmiris also want sovereignty over their own affairs.

Such results show the overwhelming desire of the estimated 12 million Kashmiris for independence. However, this in itself poses a particular problem. The options for the Kashmiris are entangled with UN resolutions dating back to 1948-49 that call for a referendum to take place for the people to decide whether they want to join India or Pakistan. If the survey reflects accurately the opinions of the people, the Kashmiris want neither, but rather prefer total independence. But independence for Kashmir is the last thing Islamabad or New Delhi wants, despite talks between the two sides that have been on and off since 2003 and gained new momentum in 2011.

K is for Kashmir

The religious dimension of the Kashmir conflict, sandwiched between Muslim Pakistan and predominantly Hindu India, has deeply ingrained their mutual hatred over the past 64 years. Pakistan is against an independent Kashmir that would united both sides and thus lose direct access to China, not to mention a major dent to its pride and the all powerful military that forms the backbone of the Pakistani nation. Azad Kashmir is integral to Pakistan. The country’s name means “land of the pure” and is an acronym, according to the general saying of: P for Punjab, A for Afghanistan, K for Kashmir, and STAN for Baluchistan. Take out the K and Pakistan would have a different meaning. India’s Hindu populace – which has become far more radical and militant over the past 20 years – would equally be against losing a major part of the Northern provinces, especially to Muslim rule.

International observers are calling for the LoC to become an international border with joint institutions developed and the U.S. to partake in ‘quiet diplomacy’ to utilize its relations with Islamabad and continue to develop alliances – particularly military and nuclear power – with New Delhi. Meanwhile Britain wants to wash its hands of the seemingly intractable problem it created in the Indian subcontinent. In 2010, when British Prime Minister David Cameron was called on to mediate over Kashmir, he said: “I don’t want to try to insert Britain in some lead role where, as with so many of the world’s problems, we are responsible for the issue in the first place.”

With international mediation, or as some may see it, interference, not likely to happen for numerous reasons, a far more radical solution is necessary. India champions itself at “the world’s largest democracy” so it would be fitting to call for a referendum on what the Kashmiri people really want rather than what New Delhi, its puppets and the dynasties, but rather the majority of the local population. Young Kashmiris think with peace this could work. The state has abundant land and resources and more than enough people for a viable country, plus a flourishing tourism sector. Kashmir is land-locked and would require the good will of its neighbors – the very same from which it would secede – for trade to become viable. Unified with Azad Kashmir, a free Kashmir would have access to the large markets of China and Central Asia.

But India is not ready. The diabolical Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) continues, permitting soldiers, quite literally, to get away with murder. There are no investigations, and an atmosphere prevails of shoot first and question later. Torture is widespread and confirmed by US cables released by Wikileaks. Visits to detention centers between 2002 and 2004 by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) revealed cases of beatings, electric shocks, sexual abuse and other atrocities.

Out of the 1,296 detainees interviewed by the ICRC, more than half said they had been tortured. Out of 681 detainees, 498 claimed to have been electrocuted, 381 said they were suspended from the ceiling, and 304 cases were described as “sexual.” A total of 294 described a procedure in which guards crushed their legs by putting a bar across their thighs and sitting on it, while 181 said their legs had been split apart.

Peaceful activists are also being targeted. In 2010, Mian Qayoom, president of the Kashmir Bar Association, was arrested under the Public Safety Act for protesting human rights violations and sentenced to up to two years in jail, while peaceful protesters engaged in sit-ins are accused by the police of “offences” and “disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servants,” while others were accused of spouting “anti-national slogans.”

The most sensational case was Booker Prize winning author and activist Arundhati Roy, who along with Gilani and five others, was jailed for “sedition” for making anti-India speeches at an event in Srinagar. Roy said of the charge in late 2010, that it “is meant to frighten civil rights groups and young journalists into keeping quiet”.

Hydro-power provides electricity to New Delhi and the populous state of Punjab while Kashmir experiences power shortages.

“Suspect All, Respect All”

A slogan on an army road block says: “Suspect All, Respect All”. This is India’s policy in Kashmir, although leaning toward “suspecting all” rather than “respecting all”. The slogan drew smirks from the young Kashmiri men I was with in Srinagar, as they witnessed little respect from the authorities. They related how during curfews Kashmiris were pulled for no reason from their vehicles at checkpoints and beaten by soldiers. They described how at hartals the army used live ammunition on the unarmed protesters. During curfews, sticking one’s head out of your front door could result in a beating. There was a sense of despondency about the situation being rectified anytime soon.

One of the failures of New Delhi regarding Kashmir is how little it has done to endear Kashmiris towards India. There has been no “nation-building” or investing in infrastructure to improve living standards. Kashmiris view the Indians as exploiting their land, natural resources and water. Hydro-power provides electricity to New Delhi and the populous state of Punjab while Kashmir experiences power shortages.

A major shortcoming is providing employment. Recent statistics show that 590,000 educated youth in the state are unemployed, while in the Chatham House survey in J&K, 81 percent of those polled said the most significant problem was unemployment, with government corruption and poor economic development in second and third place respectively. This could change in the coming years following the November 2011 decision by Pakistan to grant India Most Favored Nation trade status, which could bolster bilateral trade from 2010’s $1.4 billion. Much of this trade would no doubt go through Punjab rather than Kashmir due to inadequate infrastructure on both sides of the LoC.

The lack of work in Kashmir was reflected by the Manzars, their friends and extended family. With no opportunities in Srinagar, the men had to work elsewhere in India to earn decent wages; others went to Singapore, Dubai and Australia. This did not mean the problems of Kashmir disappeared. The Kashmiri diaspora in India keep up with what is happening through Kashmiri TV channels and newspapers particularly by following terrorist attacks in the capital due to fear of anti-Muslim and anti-Kashmir attacks.

Due to the virulent anti-Muslim prejudices of the Indian media, which jumped to conclusions that Muslims were behind the majority of bombings in New Delhi in 2007 and 2008, one of the Manzars living in the capital refused to go out on the streets for fear of arrest. Subsequent evidence has shown that in several cases it was right-wing Hindus behind the bombing rather the familiar culprit of radical Islamists. Investigations have also shown the deep-seated prejudices within the police and security apparatus against Indian Muslims. A Wikileaks cable showed that prominent politician Rahul Gandhi told the U.S. Ambassador in 2009, that while “there was evidence of some support for [Islamic terrorist group Laskar-e-Taiba] among certain elements in India’s indigenous Muslim community, the bigger threat may be the growth of radicalised Hindu groups, which create religious tensions and political confrontations with the Muslim community.”

Wazwan!

Weddings in Kashmir are major social events, bringing together families, friends and neighbors. They are one of the few positive occasions to integrate the diaspora. Weddings are protracted events, with visits and gift-giving ceremonies between the families of the bride and groom that go on well before the wedding day and into the following weeks. The festivities take place separately for the bride and groom who are united only on the wedding day once the imam has formalized the marriage.

The wedding day requires days of preparation with at least 20 cooks working for two days on the menu, the famous wazwan of dozens of dishes. Some 25 sheep, 70 chickens and 100 kilos of rice are prepared for the 280 guests, all cooked in various methods on open fires. Huge meatballs, called gostaba, are cooked slowly in sweet milk. Grilled chicken, stewed mutton, and skewered kebabs are also served.

They related how during curfews Kashmiris were pulled for no reason from their vehicles at checkpoints and beaten by soldiers. They described how at hartals the army used live ammunition on the unarmed protesters.

The morning of the wedding, Reza gets a phone call from a guest asking about the extent of the curfew. “Is the entire valley under curfew?” he asks the other seven men in the room. Yes, the whole valley. One of the guests managed to get through the checkpoints by showing his wedding invitation, but he had to go through 12 checkpoints and take alternative routes when the Indian Army would not let him through at certain road blocks. Twelve checkpoints to cover less than 15 kilometers.

Reza keeps getting calls throughout the day with cancellations and questions about the checkpoints. There is no text messaging as the Indian authorities have banned SMS in Kashmir. Will the groom make it tonight? “Inshallah (God Willing)…” The curfew tends to be stricter in the morning. The preparations continue, the people are resigned to disappointment, yet they tell jokes and drink tea. The Kashmiris are used to waiting, sitting, talking and passing the time – no jobs, schools closed, no business, and nowhere to go.

The wedding day progresses without problems and with enough guests to fill the large tent assembled in an uncle’s garden and the groom arrives that evening. The wazwan is consumed quickly but without a jubilant atmosphere due to the curfew. In the past, said the elders, the wazwan would have been eaten slower with the festivities continuing for five days rather than just two. Reza’s uncle remarked that he was one of the last to get married the old way before the troubles erupted in 1989.

The end of the wedding is however different from tradition. Usually dozens of cars accompany the new couple to the groom’s house, but Reza forbids too many from going due to the curfew. While the Indian Army says they “respect all,” they do not allow for special circumstances during curfews, even weddings.

In 2011, the Indian-administered Kashmiris have kept up the struggle for their rights and for freedom. To have effect, the hartals must continue in Azad Kashmir. Delhi will have to meet with the Kashmiri leaders instead of continuously imprisoning them and enter into constructive dialogue with Pakistan. Until a viable solution is enacted, Kashmir will remain a bleeding wound of Partition and a paradise lost. Once called the Switzerland of Asia due to its snow-capped mountains, rivers and forests, this beauty is sadly a mask for the oppression and violence that torments Kashmir’s interior. The late Kashmiri poet, Aha Shahid Ali, wrote from his deathbed in the U.S. in 2001, a poem dedicated to a Kashmiri Hindu friend:

We shall meet again, in Srinagar

By the gates of the Villa of Peace

Our hands blossoming into fists

Till the soldiers return the keys

And disappear.