The End of Arctic Friendship: Mounting Tensions in the Arctic

In Norway’s far northeast, where the Barents Sea meets the Russian border, the Arctic’s once-prized spirit of cooperation is rapidly vanishing.

Near Kirkenes, located in the Arctic Circle, lies one of the few open Russian borders with the Schengen Area. Kirkenes, a townlet on the shore of the Barents Sea, is at the centre of the geopolitical struggle for control over the Arctic. Both sides of the border are now heavily militarised and rife with security-intelligence activity.

For Russia, the area is of key strategic importance. The nearby Kola Peninsula is where not only the Russian Northern Fleet is stationed, but also the latest generation of nuclear submarines and around a thousand nuclear warheads. Close to the border lies the Olenya airbase, where the Ukrainian army recently launched a successful drone raid, destroying a number of Russian strategic bombers. At the same time, the region is exceptionally rich in oil and natural gas, while also being heavily affected by climate change. The accelerated melting of ice is already affecting the international trade routes.

Kirkenes is one of the world’s geopolitical and security hotspots.

After the conclusion of the Cold War, the Norwegian town invested significant efforts into reinventing itself as a bridge between the East and West. Yet the Russian aggression on Ukraine in February 2022 and the concomitant economic sanctions abruptly put a stop to that ambition.

Despite the dramatic decline of relations between Europe and Russia, a small part of the Kirkenes population remained favorably disposed toward Russia, predominantly for economic reasons. Before the war in Ukraine, business was booming in the border town. Also, the historical legacy of the Soviet Union within the region was far too strong to be entirely erased by recent developments.

Some 600 Russian citizens currently reside in Kirkenes, most of them opposed to Vladimir Putin’s policies. Several of them (journalists, activists, LGBT-movement members) have fled here to avoid conscription or persecution by the Russian regime. When the Russian military declared the first significant wave of forced mobilisation, several dozen Russians escaped to Kirkenes. Another, smaller portion of the town’s Russian population actively supports the Moscow regime.

Before the war, successive Norwegian governments had allocated large sums to the strengthening of the cross-border cooperation with Russia in the Barents Sea area. Seventeen years ago, both sides of the border even entertained the idea of building a ‘twin city’, which would boost Kirkenes’ ties to the Nikel Russian mining town in the Pechengsky District and perhaps even help create a ‘trans-national area’.

Such were the sentiments at the time.

To that end, in July 2008, Kirkenes hosted a meeting between the minister Jonas Gahr Støre, currently Norway’s prime minister, and Sergey Lavrov, who still serves as the Russian minister of foreign affairs. The project was halted at the purely theoretical stage. Yet the overall relation remained a close one. The Kirkenes hockey team spent a few years competing in a Russian regional league, while each year members of both sets of border patrols got together for a football friendly.

That said, several of those I interviewed in Kirkenes cautioned that parts of the abovementioned cultural cooperation have occasionally been misused for foreign-policy purposes. Or, to put it more bluntly, as tools of targeted propaganda.

Soviet legacy

“I feel bereaved, and also betrayed by former friends,” a retired medical doctor named Harald Sunde sighed next to a monument to fallen Soviet soldiers in downtown Kirkenes.

Besides his long and illustrious medical career, Sunde is also the author of two books on Norwegian partisans during the Second World War. When Sergey Lavrov last visited Kirkenes in 2019, Sunde presented him with a copy of one of the books. They shook hands. Soon afterwards, the Norwegian received a special commendation from the Russian Ministry of Defence.

On 1 March 2022, a week after the ‘special operation’ in Ukraine, Sunde paid a visit to the Russian consulate to give it back.

“The invasion was a huge shock,” he recalled, pondering the World War II statue erected in 1952. “Until the last minute, I was hoping Vladimir Putin would not follow up on his threats. The Russian attack on Ukraine destroyed all trust. And I don’t think it’s coming back anytime soon. After three decades of trying to build a friendly community, we now have a hostile regime across the border. The damage caused by the severing of ties is incalculable.”

During World War II, Kirkenes and its surroundings saw some of the most ferocious fighting in the Arctic.

The German army occupied wider Kirkenes as early as June 1940, holding the city for over four years. At the height of the occupation, some 30,000 German soldiers were in or around Kirkenes, using the town as a vantage point for attacks on Murmansk. Kirkenes was almost razed by Soviet planes fighting the Nazi forces, only to be liberated by the Red Army in October 1944.

During the Cold War, the monument to fallen Russian soldiers in Kirkenes served as a strong link in the local Norway-Russia relations. On both sides of the border, the period was treasured enough to be dubbed ‘the Arctic peace’.

Every time I visited the monument, a car painted in the colors of the Ukrainian flag was parked beneath it, sporting slogans like “Stop Putin!” and “Stop the war!” The car was owned by a Russian citizen.

Downtown Kirkenes also boasts a bronze statue of the late Thorvald Stoltenberg, the father of the long-serving Norwegian Minister of Defence and later NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. Stoltenberg senior was a key figure in linking up the Arctic countries after the demise of the Soviet Union. He founded the Barents Secretariat and headed numerous projects aimed at forging ties with Russia.

“He must now be turning in his grave,” Harald Sunde commented when we reached this second statue.

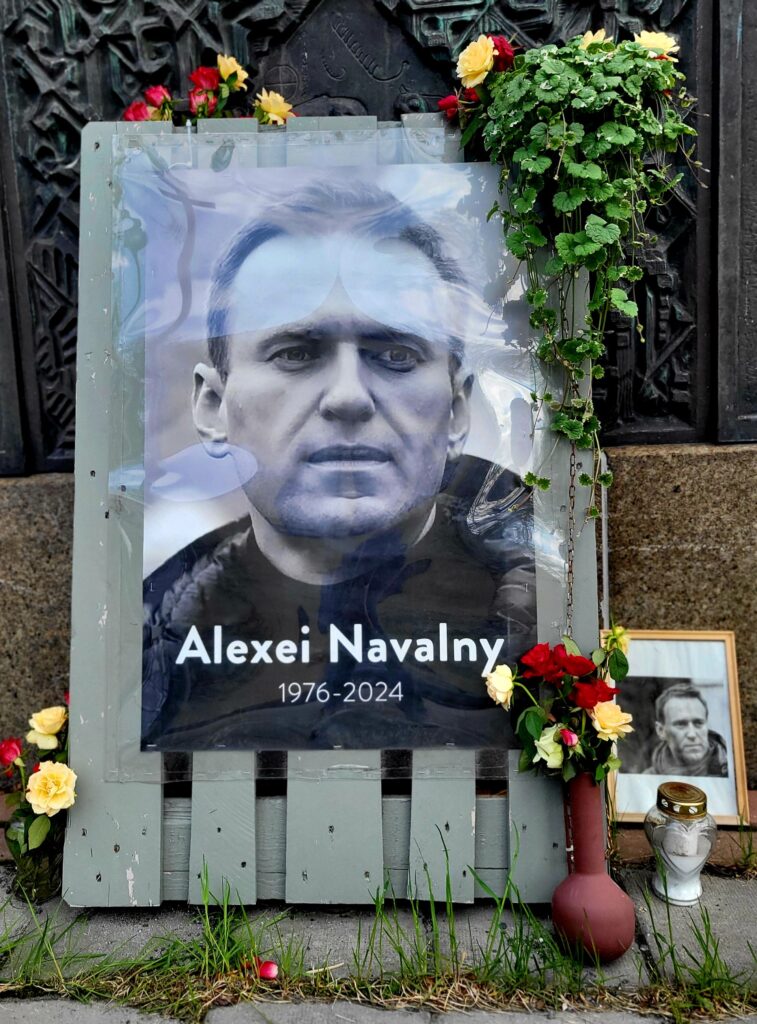

The 67-year-old history buff also serves on the city council as a representative of the socialist party. He escorted me to the memory plaque installed by the local community near the entrance to the Russian consulate after the death of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

As we took a stroll across the town’s memory lane, rife with nostalgic recollections, Sunde kept listing off the shops and companies forced to shut down due to the sanctions. The streets were frequented mainly by elderly citizens, which was no surprise, given that the young have been fleeing the area. The overall population is visibly shrinking. On this shockingly warm spring day, a few tourists were hanging around, while the low-flying seagulls shrieked hysterically, protecting their offspring. Ukrainian flags could be seen on every step.

The roadsign inscriptions in Kirkenes are written out in three different languages: in Norwegian, Russian, and Sami. Ever since February 24, 2022, the local politicians have kept up a fervent debate on whether the Russian inscriptions should be removed. Signatures were gathered; a petition was started … Yet the process of removing the inscriptions failed to gather sufficient support.

“Before the invasion, Kirkenes was an important shopping center for middle-class Russians living in towns near the border. Afterwards, many business deals were halted, many of them permanently. I expected the Oslo authorities to help out more, given the severity of the crisis,” Sunde related.

We made a brief stop by the underground shelter where the townsfolk hid during the three years of heavy Soviet bombardment at the time of the Nazi occupation. From the gaze we exchanged, it was clear we both felt that everything war-related should only belong in a museum.

The collapse of trust

The fact that Kirkenes is turning against the aggressive Russian policies was highlighted during the last yearly Kirkenes Conference. In his initial address, the mayor of the Sør-Varanger municipality, Magnus Mæland, regretfully stated that, on account of the invasion, the relations with Russia had worsened for generations to come.

“Regardless of the war’s outcome, our trust in Russia has been dealt a substantial blow, ”Mæland addressed the gathered delegates. “Kirkenes aims to provide a safe harbor for those who want democracy and freedom.”

Jonas Gahr Støre, the Norwegian prime minister, was even more direct. His opinion was that the situation in the region was at its most serious since World War II. “We must be prepared for war eventually reaching Norway, though there is no immediate threat,” Store warned at the Kirkenes Conference in May.

On June 1, the mayor Magnus Mæland fitted the front of the Kirkenes town hall building with a large rainbow flag, used in Norway to honor the pride parade for an entire month. Less than a hundred meters away, at the Russian consulate, hangs the Russian tricolor flag. This is probably the only place in the world where the two flags have found themselves in such close proximity.

“When we were putting out the rainbow flag, I took to pondering how we were living at the border between a totalitarian regime and an open democratic society,” the 41-year-old conservative mayor told me in his spacious office in downtown Kirkenes. Mæland became mayor during the autumn of 2023, a year and a half after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since then, he hasn’t exchanged a word with Kirkenes’ Russian general consul Nikolay Konyigin. The official relations have been completely severed.

“Right after the invasion, the general consul started spreading the most extreme forms of Russian propaganda. Like how Russia was fighting Nazis. How everyone in the West has turned Nazi. This was the continuation of the Second World War,” Mæland related.

In his view, the invasion came as a massive shock to the entire region, and especially Kirkenes. Yet he also believes that his constituents were quick to accept the new reality, the relations between the two border communities having already begun to deteriorate after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014.

“Putin’s regime played us for fools,” Mæland was clear. “Europe proved incredibly naive. Over here, we’ve seen 31 years of close collaboration with Russia. We are a border town. We are interlocked with our neighbors. Many of the people here were tremendously hurt. Now, all trust is gone. I fear that it will not return for several generations at least.”

“Kirkenes is a geopolitical hotspot. It is true that we share with Russia a much shorter border than Finland or Sweden. Our border, however, is located by the Barents sea and the Kola Peninsula, where Russia has enormous nuclear capabilities. The entire area is a Russian fortress,” the mayor continued.

Mæland explained that Kirkenes lies 15 minutes from the Russian border, and a mere 30-minute drive from the Pechenga valley, where the 200th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade of the Russian army is seated – a unit which has experienced heavy casualties in Ukraine. “Two more hours of driving and you reach Severomorsk, the seat of the Russian Northern Fleet, also comprising submarines with strategic nuclear weapons. And then only thirty kilometers from there, you have the Olenya airbase, where just days ago a number of state-of-the-art bombers were destroyed by Ukrainian drones.”

I asked Magnus Mæland whether he felt safe, given what he just told me. “Yes,” he replied. “Our security-intelligence services know exactly what’s going on. The same goes for the police. The Norwegian army is extremely competent. We’re in control. At the same time, we are the eyes and ears of NATO. We are essential to the European Union and the United States. The nuclear weapons on the other side of the border have never been pointed at Norway. And they aren’t now, I am certain of that.”

Mæland is well aware that the Arctic has become the new battleground for superpowers. There are many reasons: climate change enabling new trade routes, the Arctic’s plentiful natural resources (oil, natural gas, rare metals and minerals, fish) and sources of renewable energy …

The mayor of Kirkenes sees all of the above as good reasons for Europe to start constructing a new industrial base. In his view, this would be the key step towards self-sufficiency. At the same time, he denounces any form of dependence on totalitarian regimes. He advocates strict avoidance of the sort of ‘globalizing naiveté’ that rendered Germany and several other European countries almost entirely reliant on Russian natural gas.

“The solution to everything we’ve spoken about lies here, high up north.” the young Norwegian politician concluded. “While it is true we’re facing the most dramatic consequences of climate change, our corner of the world will in the future be far more habitable than other parts of the globe.”

Fishing for security

Kirkenes and two other smaller Norwegian Arctic ports are the only ports where Russian cargo ships are still allowed to dock. Most of them are fishing boats. Yet the Norwegian Security Service remains vigilant. A number of fishing vessels visiting Kirkenes over the last three and a half years were found to have modern intelligence equipment on board. For example, the Arka-33 fish-processing boat, which visited the town for several weeks in 2023.

Ben Taub, a journalist with The New Yorker, deftly utilized security sources to prove Arka-33 was gathering intelligence. The vessel was owned by a pair of Russian companies with close ties to private security firms and a Russian MP who was targeted by international sanctions.

Near the end of 2023, as many as eight highly modern Russian fishing boats, manned by 600 sailors, were docked at the Kirkenes port. None were present during the time of my visit, though one (registered at Murmansk) was being repaired at the local shipyard. For the most part, the Russian sailors docking at Kirkenes carry hand-written passports – so as to be untraceable. Norwegian intelligence is convinced at least some of the sailors are members of the Russian Northern Fleet.

Over the last few years, the entire Norwegian Arctic territory was regularly exposed to Russian security-intelligence attacks. Most of them were of an electronic nature. What can be glimpsed here is the core of a hybrid war raging in both directions. The Norwegian Police Security Service is issuing regular alerts about the possibility of Russian railway and pipeline sabotage. Numerous cases of GPS jamming have also been recorded.

Russia has been expanding its security-intelligence – or, in plain English, spying – activities across the Barents-Sea territory since 2014. This is especially true of the Russian Northern Fleet. But then this is nothing exceptionally novel in these parts. It is merely the continuation of the norm adopted during the cold war.

Since the beginning of the war, the overall traffic at the Kirkenes port has dropped by 30 percent. The main reason? Norway is no longer allowing Russian ships to anchor at its ports for repair and maintenance.

This had a significant effect on the economic condition of the border town, where a great deal of service infrastructure for Russian naval units has been constructed after World War II. The said infrastructure was the leading employer in a highly remote town, what with all the pubs, restaurants, mechanical workshops, hotels, and shops.

Over the past few months, there has even been increasing talk of possibly reopening the mine.

The real divide

Bjarge Schwenke Fors is the head of Kirkenes’ Barents Institute, a local research organization operating under the aegis of The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø.

Schwenke Fors is convinced that the deterioration of cross-border relations has caused economic havoc on the region.

Schwenke Fors related that, in his opinion, the great affection of the local population for Russia was largely mythical. He pointed to the results of a recent Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research survey, stating that only a part of Kirkenes’ Russian community supported the Moscow authorities.

“The real divide is not among those who support or oppose the Kremlin regime,” Schwenke Fors clarified. “It is between those who are trying to put a stop to local investments in the Barents zone, as well as any further investment into relations with the Russians … And those who wish the investments to continue.”

I met up with the Norwegian researcher at the seat of the Barents Institute. “My fear is that we will not be able to return to the pre-invasion state anytime soon,” Schwenke Fors cautioned.“ It will take several generations. What is certain is that the relations here have entered a new epoch. Recovery is bound to be difficult. In a number of ways, the two communities remain closely connected. Kirkenes is home to many Russians, who are an important part of the community. Just like during the cold war, when the relationship was prone to a lot of oscillation. But back then, things at least used to be predictable. These days, there is only complete uncertainty.”

Schwenke Fors believes that, after the end of the war in Ukraine, relations between the two communities will have to be rebuilt almost from scratch, mostly on account of an ever-growing sense of hostility.

The local response to the abundant Russian propaganda was somewhat predictable. Suspicion and Russophobia have begun to gnaw their way into even formerly the most open-minded citizens of the Norwegian side of the border. In Schwenke Fors’ words, the project of forging a common identity in the Barents Sea area was dead.

The Barents identity

Kirkenes lies in Norway’s second largest and least heavily settled province Finnmark. The town was founded in the early 19th century. For a long time, it was owned by a private mining company, which used it to extract iron ore. At the height of production, the mine employed 1500 workers. Yet during the eighties, lack of orders and alternative employment options brought on a severe demographic decline.

The situation changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. For a few years, the residents of Kirkenes and Nikel were allowed to travel up to thirty kilometers deep into their respective neighboring countries, with only a border pass. No visas were required.

Kirkenes’ duty-free status meant that numerous Russian ships began docking at the town port, bringing a steady inflow of merchants. Norwegians opened up a public kitchen in the nearby destitute Russian town of Nikel.

During the first half of the nineties, an intense two-way traffic was established between Kirkenes and Murmansk. Russian citizens frequented the Norwegian side of the border because they were able to purchase many things currently unavailable in their homeland. The Norwegians, on the other hand, liked visiting the Russian side, chasing cheap alcohol-fueled parties.

During the first years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian side of the border was marked by great chaos. A privatization free-for-all was taking place. Criminal syndicates took control of Murmansk and many smaller towns. Industrial pollution was experiencing its heyday, much of it caused by the mishandling of nuclear waste.

Near the end of the eighties, the Kola Peninsula hosted approximately twenty percent of all the globe’s nuclear reactors. Disused nuclear fuel continued to spill into the Barents Sea. Nuclear waste awaiting storage could be seen lying in front of shipyards and failed industrial plants.

Was there such a thing as the ‘Barents Identity’, or was it a myth, I asked Olga Povoroznyuk, a social anthropologist from the University of Vienna and a member of the Austrian Polar Research Institute with long-term research experience in Siberia and the Arctic.

»“In 1993, she replied,”the Barents-Sea countries – Russia, Norway,

Sweden and Finland – set up a new Barents Euro-Arctic Region (BEAR), a region constituted by the northern parts of Finland, Norway, and Sweden, and the northwestern part of the Russian Federation, and home to approx. 6 million people. The Kirkenes Declaration, signed that year, laid the foundation for cooperation. This important initiative did a lot to improve international relations and provided a base for developing a common identity.”

Olga Povoroznyuk has been researching the InfraNorth project, focusing on transport infrastructure and sustainability, and is currently co-leading the ARCA project about urban green spaces and climate adaptation in the Arctic. In Kirkenes, she and her InfraNorth colleagues have been focusing on the local impacts of infrastructural development and the seaport expansion project’s vision.

“At the beginning of the century, when I was finishing my doctoral studies, the idea of a common Barents identity was given a lot of attention in academic and policy-making circles,” Olga Povoroznyuk recalled the time when the regional relations were at their warmest.

She added “The shared regional identity was a subject of public debates and future imaginaries, despite the fact that the BEAR has never become a fully integrated region from a geopolitical perspective.”

According to Povoroznyuk, the relations in the region have been deteriorating from at least the Crimean crisis in 2014. “Then 2022 became a historical turning point, hugely impacting the regional identity. Where there was once close cooperation, now there is only so much distrust and frustration. Lives of many residents in Kirkenes and Sør-Varanger have undergone dramatic changes with the declining mobility, trade and exchange between Russia and Norway. The wish for forging ties has been turned into a sense of loss and future uncertainty.”

Before her current research projects, Povoroznyuk spent a few years researching on the topics of indigeneity, identity, industrial development and climate change in Siberia and elsewhere in the Arctic. “People here at Kirkenes are worried,” she related. “They feel they are nowhere near protected enough from a potential new threat. At the same time, the population is still able to draw on countless memories of peaceful coexistence from the Cold War. The emotional situation is thus rather ambivalent. The people of Kirkenes view the possibility of the town being turned into a military base as ‘the apocalyptic scenario’. Nobody wants to see that happen. Just like

no one wants any further escalation.”

In some shape or form, her words were echoed by literally all of my interlocutors in or around Kirkenes.

Northern exposure

The Barents Observer is a local newspaper covering the Arctic. Publishing the work of Norwegian and Russian contributors alike, the online publication is available in both languages. The paper may be local, but the quality of its articles meets global standards. Many who actively monitor the situation in the far north regard it as a key point of reference.

Its commitment to truth and directness has turned the paper into a constant target of attacks and sanctions from Russia. The beginning of the year saw the Russian authorities declare the publication as unwanted, while collaborating with the paper, even reposting its contents online, has been turned into a criminal act carrying a six-year prison sentence.

“A significant portion of the published materials has an anti-Russian orientation. It is noteworthy that they are being prepared by citizens of the Russian Federation who have left the country and are included in the register of foreign agents or the list of terrorists and extremists,” stated a public bulletin issued by the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation on 7 February. The Russian authorities also claimed that the Barents Observer articles were aimed at fomenting protests in the northern parts of Russia, as well as cheerleading further sanctions against the Russian Federation.

The Observers’ journalists were by no means surprised at the Kremlin move. The paper immediately released a statement of undaunted commitment to its journalistic mission, mainly investigative journalism published in both the Norwegian and Russian languages.

“What happened shows that the repressive Russian regime was aware we were good at our work. Journalism is not a crime. Trying to hinder the free press and stifle the public’s freedom of expression – now that is a crime! Vladimir Putin has built his dominance on fear. So, we shall keep demonstrating we’re not afraid of him,” I was told at the paper’s modest headquarters by Thomas Nilsen, both editor and – along with the journalists – co-owner of The Barents Observer.

In February this year, the Barents Observer won a lawsuit at the European Court of Human Rights against the Russian communication authority, which barred the paper’s reporters from entering Russian territory.

Nilsen believes an iron curtain has been drawn along the Norway-Russia border. People are growing scared. “After Russia initiated its unlawful and brutal war on European soil, we realized the most potent tool at our disposal was journalism. We decided to intensify our efforts.”

It bears mentioning that Nilsen received his own ban on entering Russian territory two years before all the paper’s other reporters did.

The Barents Observer staff comprises four Russian journalists, who fled to Kirkenes from censorship and persecution in 2022. All four are regularly exposed to Russian intelligence harassment, yet they remain beholden to their profession. Given that malign forces are following their every step, the standard of their work can ill-afford the slightest slip.

“The entire Arctic zone is becoming a major global topic. Here in Kirkenes, where the consequences of broken ties with Russia are not as severe as some claim, all of the key themes of our predicament are present. Geopolitics, climate change, the proximity of war … What happened just days ago at the Olenya airbase just across the border was a clear warning of how close the war rages. I realize very well that our reporting workload is only bound to increase,” Thomas Nilsen summed up the situation, talking to me amid photographs of Mikhail Gorbachev and framed cartoons depicting the Russian persecution of journalists, right next to a memorial room to Boris Nemtsov.

A geopolitical powder keg

In the context of nuclear safety, the virtually unknown Norwegian townlet of Kirkenes inhabits one of the globe’s geostrategically most sensitive areas – at least as sensitive as, say, Kashmir.

For over two decades now, Vladimir Putin has viewed the Arctic as a key geopolitical battleground. The Russian pressure on the region intensified with each year. Much the same can be said of the mounting NATO pressure on Norway.

After 2005, Russia began reopening more than 50 old Soviet military bases on the Kola Peninsula. According to my interlocutors, at least a thousand nuclear warheads – Russia’s second largest nuclear arsenal – are now located within a radius of two hundred kilometers. The Kola Peninsula also hosts hypersonic-rocket firing ranges and the world’s largest ice-breaker fleet. One of the icebreakers is fueled by a nuclear reactor.

Yet even with such an embarrassment of riches, Russia’s most important strategic resource in or around the Barents Sea is its super-modern nuclear submarines. A single one can carry 16 ballistic rockets with nuclear warheads, which can be fired from the depths of the sea. These submarines form the basis of Russian strategic safety, and remain Moscow’s absolute priority. The map of the Kola Peninsula thus reads like a map of Russian geo-strategic security.

Incidentally … October 30, 1961, saw the Soviet army trigger the largest detonation of a nuclear weapon in history. The explosion was three thousand times more powerful than that of Hiroshima. The detonation occurred at the Novaya Zemlya island in the Barents Sea. Norwegian soldiers in the north of the country were able to observe the glowing skies, even though they were a thousand kilometers away from the explosion.

Rapid militarisation

The land border between Norway and Russia measures 195,7 kilometres in length, the sea border 23,2 kilometres. The only land crossing station is located at Storskog, some ten kilometres from Kirkenes. The border was demarcated in 1826 and remained virtually unchanged until the present.

The Storskog border crossing gained prominence between 2015 and 2016, when it was used by several thousand refugees and asylum seekers from Russia to enter Norway. During the last three months of 2015 alone, over 5,000 of them crossed the border.

Most numerous among them were Syrian citizens. They reached Norway by bicycle and even wheelchairs, since it was forbidden to cross the border on foot. The Norwegian intelligence officers identified several persons hired as agents by the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation. This was one of the reasons the border was closed to refugees, while Russia was placed on the list of safe countries for refugees. Private vehicles with Russian license plates were barred from entering Norway in May 2024.

During my visit, the crossing was used from the Russian side by a pair of buses carrying Chinese tourists. The infrastructure surrounding the crossing station is rapidly deteriorating.

The heavily militarized Russian side of the border is controlled by the state’s border service, while the Sør-Varanger region garrison patrols the ever more militarised Norwegian side.

The entire border area is riddled with security-intelligence structures – the most imposing of them being a trio of enormous radar domes located at the Vardø fishing village and controlled by the Norwegian army. Over the past few years, the said army has been using the area to train members of Ukrainian special units.

Nikel is the first larger settlement on the Russian side, marked by a number of tall chimneys. Not so long ago, when the plant was still operational, the air and water on both sides of the border were heavily polluted.

Near Nikel lies the famous, more than twelve-kilometre deep hole – the deepest known hole in the world. It was created by Soviet engineers in the 1970s, aiming to drill their way to the Earth’s core.

They failed.

The hybrid war

“The Arctic is witnessing the consequences of the aggression on Ukraine. Russia is actively promoting a narrative of NATO militarization of the Arctic and has for several years been bolstering its Arctic military positions, opening new outposts and upgrading old ones,” I was told over the phone by Kari Aga Myklebost, professor of Russian history at The Arctic University of Norway.

According to her, Russia has increased its efforts to create a hostile image of the West from 2022 onwards. By flying Soviet flags and cobbling together approximations of military parades at the Russian settlements in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Barents Sea, Russia is trying to force Norway to react.

“The incidence of Russian symbolic activity rose sharply after the full-scale attack on Ukraine. Russia stepped up its public commemoration of May 9 as Victory Day, placing a further emphasis on its legacy from World War II while also glorifying the current war in Ukraine. This is Russia’s current mode of hybrid operations in Svalbard: Russia is strategically taking advantage of Norwegian freedom of expression and use of symbols. The aim is to provoke a reaction by forwarding revanchist symbols, as a sharp reaction would open up for accusing Norway of discrimination against the Russian population. From 2022 on, we’ve seen many such cases in Svalbard,” professor Myklebost explained.

In her opinion, Norway plays a rather important role in Russia’s long-term plans. “As a small country bordering the strategically important Kola Peninsula and the adjacent Barents Sea, Norway is rightly very cautious. The balance of power is extremely asymmetric, and these regions are of high military-strategic importance to Russia. Norway is well aware that Russia could potentially start mounting pressure concerning the Svalbard archipelago.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Norwegian authorities invested a great deal into forging relations with Russia across the border in the north, especially in and around Kirkenes. After 2022, the relation-building was halted. In Kirkenes, relations with Russia have become a rather sensitive topic.

War commemorations such as Russian Victory Day, which used to be celebrated jointly by Norway and Russia in Kirkenes, have become controversial. According to Myklebost, Moscow – through its continued war commemorations – keeps up a narrative of cross-border unity in fighting German Nazism as well as Neo-Nazism in Ukraine today. »And this is done despite the fact that many Kirkenes residents have very clearly expressed their disapproval of Russian commemorations trying to establish a link with the war in Ukraine. The Russian consulate continues with its provocations.”

As one of the leading authorities on Arctic geopolitics, Myklebost is convinced that Kirkenes itself doesn’t hold a very high strategic value for Norway, even if it is of importance to NATO as a whole due to its proximity to Russia. Whereas for Russia, the case couldn’t be more different. “Both Svalbard and the Barents Sea are of exceeding importance to Russia. In case of conflict between Russia and NATO, Russia would need control over the eastern part of the Finnmark province as well as the Barents Sea to secure its strategic capabilities on the Kola Peninsula and free access for its Northern Fleet into the Atlantic Sea. This would also involve control of Kirkenes, Svalbard and the western part of the Barents Sea. The key aims would be to secure the Kola Peninsula’s nuclear capabilities and grant free navigation to the Russian Northern Fleet.”

The Chinese factor

Weeks ago, Kirkenes’ port director Terje Jørgensen stated he wanted to build a new port terminal, aimed at connecting Northern America, Europe and Asia. The said terminal would mainly service Chinese freight ships, granting China precisely what it most desires. Namely, an important step in setting up the so-called Polar Silk Road. Though it also has to be said that the ‘northern-Singapore’ cliché has been a part of Kirkenes’ public debate for so long it has already grown rather stale.

“The fact is that the Kirkenes port needs investments and activity. This is why the director expressed his openness to economic collaboration with China. My personal sense is that the Norwegian government will not allow it, on account of security reasons,” Kari Aga Myklebost reasoned. The professor pointed out Russia’s close strategic ties with China, the two countries even having conducted joint military exercises in the Arctic.

“Norway fears that the potential Chinese port infrastructure at Kirkenes could be used for double purposes. Or for various purposes at odds with Norwegian national interests,” Myklebost concluded.

The Norwegian intelligence services are increasingly concerned by the semi-recent changes in the White House, as well as by the Americans cozying up to Russia while setting their sights on the acquisition of Greenland. The north of Norway has been caught up in the middle of a geopolitical upheaval.

“Norway is adapting to changed circumstances. On the one side, we have a very determined Russia, and on the other the extremely unpredictable American administration. In this context, the Norwegian government announced in May that it intends to soften the restrictions imposed on its allies seventy years ago, concerning activities in the areas bordering on Russia. This is a huge change, as the restrictions were partly intended as a message to Russia,” Kari Aga Myklebost related.

Like Finland and Sweden, Norway has been bolstering its national defensive capacities with the aim of containing Russia. “This is the reality. For the time being, we are simply not in a position to plan our future relations with Russia. The situation is much too unpredictable.”

The melting of the North

Another key factor adding to the growing tensions across the Arctic is climate change.

Over the past four decades, each decade on average saw the melting of 13 percent of summer ice. And the trend is only mounting. At this rate, the Arctic might be rendered ice-free by 2040 – a prediction reading like a global declaration of war. At the same time, the melting of the ice is already opening up new trade routes. Some of them lead across the Barents Sea. Very soon, the Northern Sea Route will be open throughout the year.

All Arctic countries except Russia are NATO members. The Euro-Atlantic military alliance has recently been joined by Norway’s long-neutral neighbors Sweden and Finland. Russia, which controls over two-thirds of the Arctic alone extending 5600 kilometers in length), was expelled by the Arctic Council in 2022. All scientific contact has also been severed, causing untold damage to our common understanding of the changes sweeping the Arctic region.

Before the Russian attack on Ukraine, the Norwegian authorities were planning on turning the Kirkenes port into a significant logistical base connecting Europe and western Siberia. Of paramount importance would be an oil and gas terminal linking up with the nearby Finnish town of Rovaniemi, and from there with the Finnish railway system. But the Russian invasion was not the sole factor putting a stop on the ambitious project. Norway also had excessive expectations of its earth-gas drilling projects in the Barents Sea.

Norway, which is currently presenting itself as one of the globe’s greenest countries, is still intensively seeking out fresh deposits of oil and earth gas. The Arctic has been estimated to contain some 30 percent of the world’s gas reserves.

According to oil analysts, the Barents Sea holds two-thirds of Norwegian oil and natural gas reserves. In 2022, when the European energy system was thrown in a panic in the wake of the attack on Ukraine, Norway opened up 93 new drilling sites. 71 of them were located in the exceedingly sensitive Barents Sea ecosystem. Over the 2022 period, oil and earth gas formed 73 percent of the entire Norwegian exports.

According to Continental Shelf Department data, December 2023 saw Norway break a six-year record regarding the amount of earth gas extracted in a month (379 million cubic meters). At the end of last year, Norway was on average exporting 1,85 million oil barrels daily to the European Union.

Fossil fuels remain one of the key driving forces of war.