Ghana: West Africa’s Emerging Renewables Hub

With over 75% of the primary energy coming from its own renewable resources, at first glance one could conclude that Ghana today is close to self-sufficiency; however, the actual rates of access to energy services are low. A favorite for business and entrepreneur opportunities, the country is building a solid commitment with policy, technology and industry players to emerge as an African champion of energy access from renewable sources before 2020.

As the second Sub Saharan African state to gain independence from colonial powers (Liberia was the first one, in 1847), Ghana celebrated its 56 years of sovereignty in March 2013. This can also be the year to celebrate the countdown towards achieving energy independence. An exemplary case of socio-political stability in Africa, Ghana is a favorite for business and entrepreneur opportunities, being the 1st West African country in the 2012 World Bank ranking for doing business; and 5th African country behind Mauritius, South Africa, Botswana and Tunisia.

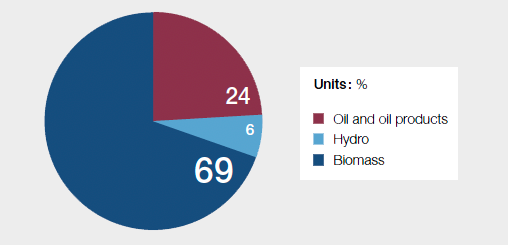

Recent oil and gas discoveries have awakened international interests and put Ghana on the list of energy-relevant regions of the world. How does the energy picture really look in Ghana? The country’s gross energy supplies (known as primary energy, Figure 1, totaling 9240kTOE in 2009) are mainly dependent on traditional biomass, often traded on a non-formal – and therefore not recorded – basis, followed by oil, and then a smaller contribution by the hydroelectric plants in Akosombo and Kpong (Lake Volta).

Since over 75% of the primary energy is obtained from its own renewable resources, one could be inclined to conclude that Ghana is already very close to self-sufficiency and in a very sustainable manner. However, this is not entirely true since the primary energy supply figures only reflect the origin of energy and not the way in which it is used. What brings effective wealth and enables productive activities are the availability of modern energy services, namely electricity, LPG, transport fuels, natural gas, biofuels and mechanical power (UNDP-WHO, 2009). Two aspects must be considered here: how the primary energy figures turn into forms of usable (modern) energy, and the rate of access to each of these forms.

Looking at the uses of energy in Ghana (known as final energy, Figure 2, totalling 7895kTOE in 2009), about 40% of the total consumption in Ghana occurs under some form of modern energy. The difference between the total primary energy supply and the final energy use are the losses (15% in 2009), mainly given in oil refineries, electricity generation and electricity transport.

Regarding the rate of access to modern energy, a study published in 2010 quantified the national average rate of access to electricity to 60%, which, despite being an outstanding achievement compared to neighboring West African countries, was equivalent to nearly 10 million people being without access to electricity (IEA, 2010). This lack of access occurs mostly in rural areas (where the rate of access is estimated to be just about 25%), far away from the main cities and district capitals. The regions with the lowest access to electricity are the Northern, Upper East and Upper West Regions.

| Region | Electricity Access Rate – Mid 2010 |

| Ashanti | 82% |

| Brong Ahafo | 67% |

| Central | 81% |

| Eastern | 70% |

| Greater Accra | 97% |

| Northern | 50% |

| Upper East | 44% |

| Upper West | 40% |

| Volta | 65% |

| Western | 68% |

| National Average | 72% |

The Strategic National Energy Plan (SNEP) for 2006-2020 includes a national goal to achieve 100% national electrification by 2020 and a strategic target to achieve 30% penetration of rural electrification via renewable energy technologies by 2020. This target is also quoted as a contributor to the goal of achieving a 100% security of supply fostered by the periodic episodes of drought experienced in the recent years, which affect the hydroelectric generation capacity (Brew-Hammond & Kemausuor, 2007).

Regarding the rate of access to modern fuels or to mechanical power, there are no such detailed figures as for the access to electricity; a joint study by UNDP and the WHO estimated that an average of 27% (urban) and 2.5% (rural) of the population had access to electricity, gas or kerosene as primary cooking fuels in 2008. For the specific case of the transport sector, being (until now) an oil importer, Ghana has one of the higher gasoline and diesel prices in the region.

Considering the figures on energy uses and access, our initial conclusion on Ghana’s energy clean self sufficiency becomes clearly precipitated, but the good news is that country is taking solid steps towards achieving it, and before 2020.

After numerous pilot projects by national and international developers, the policy ice-breaker was probably the inclusion in the SNEP (2006) objective to increase the use of renewable energy sources to 10% of the national energy mix by 2020. Then, in December 2011, the Renewable Energy Act 832 was passed by the Ghanaian Parliament; this exhaustive and well-organized regulation addressed 4 key aspect

75% of Ghana’s primary energy comes from renewables.

• Appointing specific roles and responsibilities to institutions, led by the Energy Commission and the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC).

• Setting up of a licensing framework for the commercial activities of renewable energies.

• Establishing a financial framework to promote electricity generation from renewables, via the creation of a Feed-in-Tariff scheme (guaranteed selling price to the utilities for a minimum period of 10 years), combined with a Renewable Energy Purchase Obligation, which forces power distribution utilities and bulk electricity consumers to purchase a certain percentage of their energy requirement from renewables. Both mechanisms are further regulated by the PURC.

• Setting up of a Renewable Energy Fund nurtured by finances approved by Parliament, premiums, donors, levies from fuels export, and aimed at supporting research, promotion, deploying renewable energy infrastructures.

Financial hub: the country’s stability and robust policy framework on renewables, together with the incentives put in place, are crucial for national and international investors, who seek long-term guarantees to ensure reasonable returns over the life-time of a project (which may last for more than two decades). Even in rural, very low income areas, Ghana has a story to tell: the ARB Apex Bank has succeeded in adapting its services and previews to facilitate flexible loan reimbursement models to over 90,000 customers by the end of this year (IRENA, 2013).

Such a policy stepping stone would not have been possible without the backing of Ghanaian research, industry and civil society, as well as the interest of international investors, that are shaping Ghana as the renewable energy hub of West Africa, with multiple components:

Research and Technology hub: Ghanaian technical research institutions are well-linked with top U.S., Asian and European counterparts, as well as with other African centers, and more recently the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) has become a reference in the fields of solar energy and biomass, training hundreds of future African scientists and engineers every year. More precisely, the feasibility of electricity generation from biomass will be analyzed during this year in a joint study by the Kumasi Institute of Technology, Energy and Environment (KITE), KNUST and the Technical University of Catalonia – Barcelona Tech (UPC) in Spain.

Industrial and Transnational hub: the entrepreneurial nature of Ghanaian industry has also reached renewables, which today counts on several companies with large experience in the country and around West Africa, and who often collaborate with international companies, especially from China, Germany, Spain and the U.S. The foreign investor can easily find local business partners. As for cross border electricity inter-connections, Ghana plays a central role in the West African Power Transmission Corridor (from Nigeria to Senegal), thus being in a privileged position to export clean energy.

Like other hubs, setting up has been a first great achievement for Ghana. The next step is to keep public and private investment flowing. This is a goal being fostered by the Minister for Energy and Petroleum, Emmanuel Armah-Kofi Buah, who announced advancing the target year to 2016 for achieving universal access to electricity in Ghana. This ambitious benchmark was met positively by a series of large investors currently competing to develop in Ghana what will be the largest solar plant in the entire African continent.

References:

• AEA (2010). National Electrification Scheme (NES) Master Plan Review (2011-2020). Arthur Energy Advisors for the Ministry Of Energy, Accra, 2010.

• Brew-Hammond, A. and Kemausuor, F. Eds. (2007). Energy Crisis in Ghana: Drought, Technology or Policy? Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), College of Engineering, Kumasi, Ghana, 2007

• IRENA (2011). Renewable Energy Country Profiles Africa. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, 2011.

• IRENA (2013). Africa’s Renewable Future: The Path to Sustainable Growth. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, 2013.

• UNDP-WHO (2009). The Energy Access Situation in Developing Countries – A review focusing on Least Developed countries and Sub Saharan Africa. United Nations Development Programme and World Health Organization, New York, 2009.