Real Change Begins Where Extremes Meet

Through ice storms and innovation, this polar explorer proves climate solutions can be born in the extremes.

From crossing the Arctic Ocean to building the world’s first zero-emission polar research station, Belgian explorer Alain Hubert has lived on the frontlines of climate, science, and survival. As the co-founder of the International Polar Foundation, Hubert speaks about the lessons drawn from nature’s harshest environments, how ice reveals the story of our species, and why the real challenge today is not technological, but human.

You’ve had an extraordinary life as an engineer, explorer, and mountaineer. What first drew you to the polar regions, and how did those experiences shape your worldview?

First of all, it’s not a career, it’s passion, because I don’t earn money with that. I started my childhood next to a forest here near Brussels. I used to say that my first expeditions were in that forest.

A long time ago, we had a lot of snow in the winter. It was completely different. I started running out into the middle of nature. Then, a bit later, when I was 15 years old, I discovered mountains. One day I was doing an easy climb and ended above the clouds. For me, it was the sunset, and that was a revelation. I knew I was becoming a mountaineer.

Being a mountaineer means you are not fighting against someone, you are in front of yourself, in front of nature. And nature is harsh, rude, and doesn’t care about you. That was something very important in my life: realising that we are supported by the Earth and nature, not the other way around. It’s not that we dominate everything on Earth.

Being a mountaineer means you are not fighting against someone, you are in front of yourself, in front of nature.

Later, I went to the Himalayas, where it’s even more extreme and difficult. It was only when I was about 38 years old that I decided to try to reach the North Pole. That was a dream since I was a kid, because of a book hidden somewhere in the library at home.

I went to the North Pole from Canada, an expedition of about 76 days, in the middle of this ocean that we don’t know. The Arctic is an ocean covered by ice, moving all the time, even if it’s minus 50 degrees Celsius. You never know what’s going to happen in the coming hours. You have to live in that environment.

In front of danger, the only way to save your life is to change your behaviour. That’s a big thing for a sportsman like me, with a bit of ambition. But then you realise that to succeed or not, you have to take the material and conditions into account. I reached the North Pole after a journey and a big storm in the middle of nowhere.

And then when you arrive at the North Pole… you’re not there anymore. That was 1994. We had the first GPS, a big thing, 1.5 kilos, which failed a few times. But we were able to attest that we were at the North Pole. But a minute after, you’re not at the North Pole anymore. And that’s something a bit disturbing.

After reaching the North, you decided to cross Antarctica. What did that expedition reveal to you about the role of science, and the significance of the poles?

That was important in my life. I decided to attempt the crossing, the longest crossing of Antarctica which is about 4,000 kilometres. And I was asked by French scientists to do some science for them, crossing new territories, which I accepted. I had to study a little bit, what are those scientists doing there, in the middle of nowhere?

Like everyone else, I started asking: why do we have to go there? What’s the role of the poles in our daily life?

Well, in Antarctica, the temperature is always below 0 degrees Celsius and the snow never melts. These small bubbles get trapped into the crystals of snow and, after a long time, they stay. That snow becomes ice. Scientists gradually drilled through the ice, it started a long time ago, in 1957, during the International Geophysical Polar Year.

There’s a story of a French scientist who put ice from Antarctica in his glass of whisky and saw bubbles coming out. That was the beginning of all the science developed to understand what’s in these bubbles, which were trapped for hundreds, thousands of years.

The EPICA project drilled more than 3,000 metres deep. We retraced the composition of the low atmosphere going back 800,000 years. Eight glacial and interglacial periods. We discovered the variation in CO₂ concentrations, the main greenhouse gas we talk about today.

Thanks to these ice cores, we know the origin of the problem we have to face today. It’s an anthropogenic cause, caused by the exploitation of fossil fuel energy. As an engineer, when you know the cause of a problem, you know what to do to work on the solution.

As an engineer, when you know the cause of a problem, you know what to do to work on the solution.

This is the first time in human history that we know there are limits. And we also know what to do to try to cope, through mitigation or adaptation.

You went from going on expeditions to creating infrastructure by founding the Princess Elisabeth Antarctica Station. What made that possible?

After my big expedition in Antarctica, I wanted to start a foundation, a platform between science and society. Not just for basic education, but to explain why science is important today, to look for solutions and change the world.

Then came the idea for the station, a few years later. The old Belgian station was isolated, but important for science. So we went to the government and proposed to build a new one.

Scientists said, “We don’t need a station along the coast, we have to go inland.” I had started my expedition from that inland area, so I knew the terrain.

In 1992, the nations of the Antarctic Treaty adopted the Madrid Protocol, advising members to be careful with the environment. But, as often in big international treaties, you do what you want. It wasn’t effective.

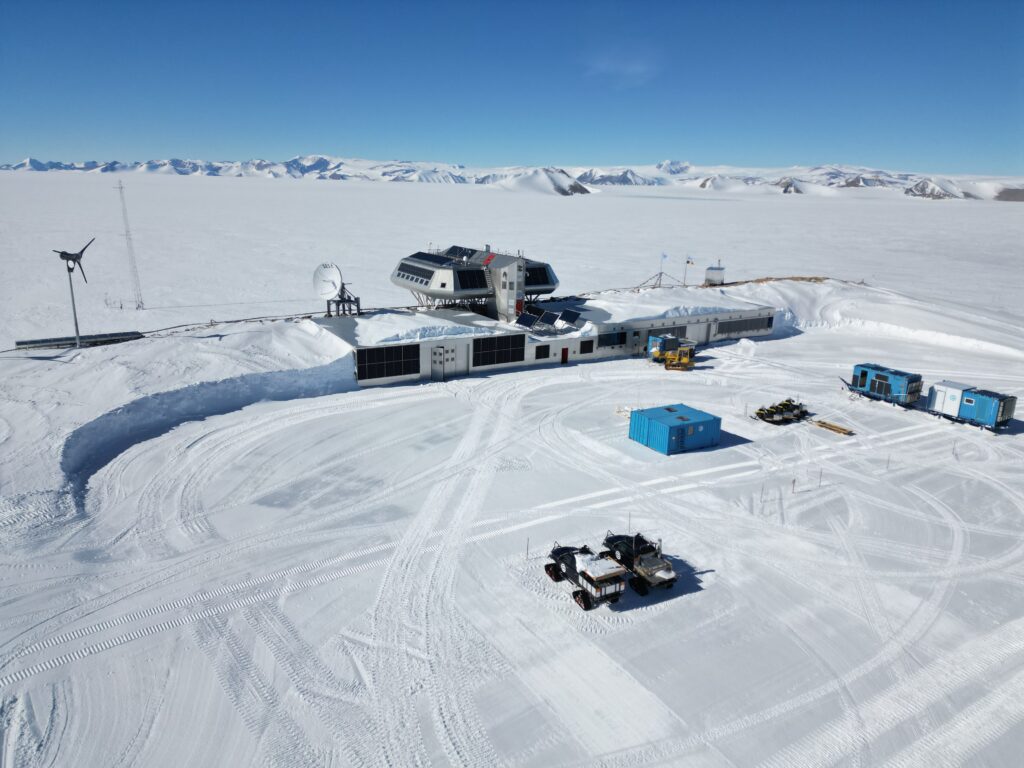

So, for us, it was natural to say: why not try to make a zero-emission station? Bringing fuel to Antarctica is hugely expensive anyway. We conceived the first smart grid of its kind. Today, the station is fully zero emission. We developed a water treatment system that is 99.6% perfect. When we leave at the end of the season, only one “person” stays, we call him James. He’s the computer. The station doesn’t need people during winter. All energy is provided by wind, stored in batteries, and monitored via satellite.

One of your founding ideas was to close the gap between science and society. Are we getting closer?

You don’t have to take action in the polar regions, you have to take action elsewhere. But we, as a small country, showed that zero emission is possible. Nobody can say anymore, “No, it’s too complicated.” It is complicated, but it’s possible.

The change will only happen if we change our behaviour. We are still stuck in the mindset that we have to produce more, grow more. But now we are 8 billion people, and we have to live together on this planet.

There’s no plan B. Space is not an option. When I was a kid, we didn’t even have a TV. And now, look at everything we’ve built in 60 years. But for what? The big question is: can we use our intelligence, all the technologies we’ve created to survive on this planet together?

Let’s talk about the future. What’s the vision behind the Andromeda Earth Observatory?

Princess Elisabeth is a small station. It can host 50 people, which is not bad for Antarctica, but the smart grid can’t be extended.

So if we want to go one step further in environmental performance, and even in space technology that we can test here on Earth, we need a bigger place.

We also built an ice runway 60 kilometres from the station to give Belgium independent access. And now we are developing the Andromeda project, an international project to give easier and cheaper access to scientists from all over the world.

It will be the most environmental station in Antarctica. We plan to set up a university Antarctic research centre, satellite activities, and open the Antarctic to global science. The future will depend on how well we work together.

In the documentary that you were featured in, there was this statistic that in 2024 the world has lost 450 gigatons of ice. In this interview you are on a more constructive attitude. How do you keep being positive when everyone is so concerned and negative?

First, nobody can tell you exactly what’s going to happen in 50 or 100 years. But what’s interesting is the dynamic: the energy in society from people and companies. If big companies don’t want to change, politicians won’t change. The system is short-term. But what we need is long-term action. That’s the challenge.

If big companies don’t want to change, politicians won’t change. The system is short-term. But what we need is long-term action. That’s the challenge.

This revolution, it’s about bringing the human back to the centre. How will we use the technology we have? That’s the infinite challenge. But it’s also the first time in human history that we know what we have to do. The question is: can we do it, together?

If you’ve had the chance to live your dreams, to become a polar explorer, to convince entrepreneurs to change, well, it would be a pity to be negative. I prefer to stay hopeful.

And finally, if you had two minutes with EU leaders, what would you urge them to do to protect the poles?

The poles, especially Antarctica, are the place to go tomorrow. That’s where we can understand the speed of change.

Climate is an exchange between cold and heat, between ocean, atmosphere, and land. There are only two cold sources: the North Pole, which is disappearing, and the Antarctic, the main cold source of the climate.

We’re seeing more extreme events, that’s a signal. And we need science to give us the facts, facts that tell us how much time we have to act.

And please, I’m fed up with the idea that we need a catastrophe to start changing. Are we stupid as humans? What makes us different is our ability to understand what’s happening, and to make decisions. That’s the future.