Water Resilience Starts Upstream

Over $1 trillion is needed over the next 25 years to fix, replace, and expand drinking-, waste-, and storm-water systems in the United States of America. If done properly, such massive capital investments will set us on a more sustainable path for people, wildlife, and biodiversity. Doing it right means reframing the problem space for nature and the most vulnerable among us to be at the heart of future water resilience.

In the summer of 2018, residents in Oregon’s capital city, Salem, got a cell phone alert stating: “Civil emergency. Prepare for action.” People in Oregon State know that we are due for a major earthquake and thought the Big One was happening. It was a shock to many that the emergency alert was, instead, for drinking water. A toxic algae bloom had made city water undrinkable and continued to do so for nearly a month. But those who were not surprised were municipal water managers – in Salem, and in communities around Oregon. They all know it can happen to them too.

The Salem incident is a red flag for drinking water providers everywhere that rely on surface waters (streams, rivers, and lakes) which applies to hundreds of towns in Oregon alone. Toxic algae blooms are expected to increase in frequency and duration. As Oregonians witnessed over last summer, as temperatures rise, so do the threats. Longer summer droughts, more intense and prolonged fire seasons, less reliable winter snowpack, lower summer stream flows, and more frequent, extreme rain events – all are changing the face of water management and laying bare a fact we have ignored at our peril: our public health depends upon ecosystem health. But drinking water woes are also a social justice issue because the people most affected are the low income, children and the elderly.

Add to these challenges the need to upgrade aging infrastructure, which includes a vast backlog of deferred maintenance on pipes and treatment plants. In Oregon and our neighbor Washington State, more than $15 billion dollars is needed for drinking water infrastructure repairs and improvements over the next 20 years. In the same period, we also expect to add another 3-5 million residents – all of whom will need clean water.

Our public health depends upon ecosystem health.

How we approach water issues over the next decade will have far-reaching consequences. The worst thing we can do is to try to solve these problems using the same approaches that created them. It is time to invest in distributed and greener technologies along with our natural infrastructure of soils, trees, wetlands, rivers, and open spaces.

Invest in Nature: The Original Hydro-Engineer

Water infrastructure is a buzzword in every U.S. community as local governments and utilities struggle to meet current demands and plan for population growth, plus the uncertainties of a changing climate, and a host of new environmental threats such as “emerging contaminants, ” including pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and endocrine disrupting compounds.

Traditionally, municipal water utilities – those that provide drinking, storm, and waste-water services – have relied primarily on “grey” infrastructure solutions of concrete, steel, and chemicals. Civil-engineered approaches to managing water like dams and centralized water treatment facilities are expensive to build and require perpetual funding to maintain. More problematic is that they typically fail to recognize nature as an asset, thereby often degrading fish and wildlife habitat and amplifying negative changes in the local hydrologic cycle.

Nature is the original (and best) hydro-engineer. We know that when watersheds are healthy, they store and filter water more affordably than many human-designed systems while providing many other benefits for people and wildlife.

Nature is the original (and best) hydro-engineer.

Nature-based solutions for drinking water are those that protect or recover watershed processes which mean better water quality and supplies. Examples from the Pacific Northwest include re-planting river banks and unstable slopes with native vegetation and decommissioning old forest roads to reduce erosion, re-creating strategic log jams in-stream to encourage gravel deposition, and allowing beavers to repopulate places where their dams can slow flood waters and trap sediment.

No single entity can restore or protect watershed health on their own, which is why we co-founded the Drinking Water Providers Partnership. The first of its kind, this public-private coalition incentivizes watershed restoration actions that benefit native fish habitat and drinking water supplies in the Pacific Northwest.

The Partnership includes 3 federal and 2 state agencies and 2 non-profits that direct financial and technical support for voluntary restoration projects carried out by drinking water providers, conservation practitioners, and upstream land managers. The Geos Institute’s Working Water program administers the grant process that to date has awarded $1.3 million to support 37 drinking watershed restoration projects in Oregon and Washington.

Not only have we learned about the drinking water threats that towns around the region face, our experiences have taught us that we are not going to fix what’s upstream without also fixing what’s downstream. Protecting and restoring rivers and uplands are a commonsense and cost-effective strategy for enhancing biodiversity, protecting public health, and saving money. However, through conversations, site visits, and research, we realized that we are not going to achieve landscape-scale conservation wins or routinize the inclusion of nature-based solutions in drinking water management until we expand the problem space to the systems level. That means looking at:

- all municipal water management – drinking, storm-, and waste-water – within the context of its watershed

- the regulatory and institutional framework of traditional infrastructure design and investment decisions

- the social make-up and economic capacity of each community

Up-ending The Status Quo

To create meaningful change, whereby towns routinely incorporate nature and regenerative solutions into municipal water services management, we must break down the silos that limit our creativity and problem-solving prowess: rural vs urban; drinking vs waste water; markets vs philanthropy; trees vs cooling towers; concrete vs beaver dams; up- vs down-stream.

All cities and towns face the dual issues of crumbling infrastructure and environmental change.

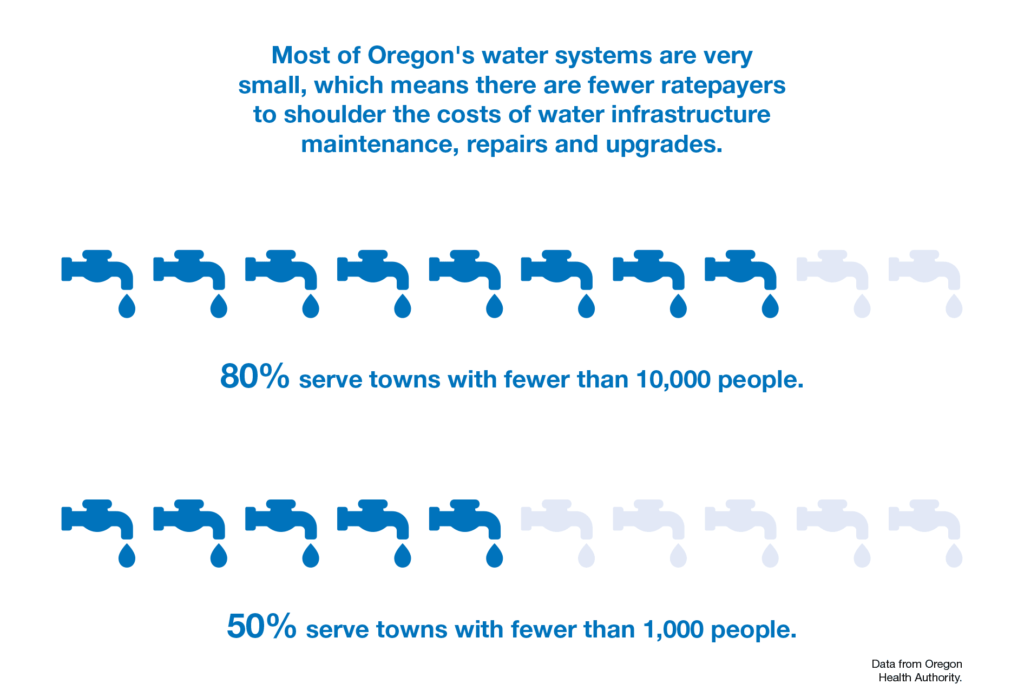

All cities and towns face the dual issues of crumbling infrastructure and environmental change. The key difference among them is that small and poor towns typically do not have the resources to go beyond the status quo. Understanding this is key to fostering resilient ecosystems and human communities everywhere.

Innovation in the municipal water sector – whether that’s ecosystem service payment schemas for drinking water source conservation, or engineered wetlands for wastewater finishing treatment – favors places that can obtain and dedicate funding to staff and consultants to invent and advocate, shoulder labyrinthine administrative requirements, parley rule exemptions, and navigate multi-year permitting processes. As a result, innovations are incremental and nature-based solutions are limited to case studies and metropolitan areas, particularly for municipal storm- and wastewater systems.

While larger metropolitan areas serve most people, the majority of cities and towns are small; and in small and economically disadvantaged towns, undercapitalization takes many forms, from an inability to access the bond market to staff juggling multiple roles just to keep the town running. Basic, yet essential, activities like water asset inventorying, source water protection and holistic long-term planning often do not happen even though the water source and surrounding areas for these towns are some of the best, most intact forest and agriculture habitat.

From the deleterious impacts of high organizational burdens and transaction costs to disincentives for one-water management, it is easy to see why the most celebrated of smart, sustainable projects are associated almost exclusively with metropolitan and more economically prosperous areas. The players and institutions involved in municipal water infrastructure decisions operate under the same forces of power and privilege that rule other sectors of society. Not surprisingly, an inefficient and inequitable system underpinning our most critical public services makes us all less effective and continually puts nature at a disadvantage.

Yet the way we define our water management and infrastructure problems is a prime determinant of what we build, how, and who funds it. Now is the time to re-define our water infrastructure and management needs with nature and equity at its heart.

A Geography of Opportunity

The resources already exist to upend the status quo. There are community leaders in towns of all sizes who are eager to do things differently. There are private investors and funders who are interested in nature-based solutions to water management challenges, but they cannot always find sufficient “ripe” projects to fund. And there are a plethora of non-profits competing for limited grant dollars to implement nature-based solutions, which need to move beyond case studies to be widely replicated. We need to merge these interests better so that they can reach their full potential. Here are three essential changes we can start today (at least in the Pacific Northwest of the USA):

1. Address drinking water source conservation with the same rigor that we consider waste- and storm-water management, thus creating a “one water” management system.

This may require regulatory changes, but should at least include scientifically-defensible environmental vulnerability assessments for every municipality – large and small. This identifies priorities for restoration and protection and levels the playing field so that smaller towns are no longer at a strategic disadvantage when they enter into a water infrastructure-management decision space. This can help vulnerable towns in the Pacific Northwest mitigate for harmful algal blooms – and other changes associated with a warming climate.

2. Adopt one-water management and community-based design processes as standard practices in every community.

One-water management facilitates resilience by considering our interconnected systems from headwaters to wastewater treatment plant outfall along with forecasted climate change impacts. For example, in an inventory of assets that includes the condition of a community’s drinking water treatment facility, the scope would broaden also to consider current and anticipated environmental conditions in the source area. While this seems like commonsense, it is not currently happening. And, when capital project choices need to be made, participatory and community-based design processes serve to elevate design criteria like adaptability, equity, affordability, and sustainability. Done early enough, these steps encourage people to look beyond only satisfying regulatory requirements and minimizing costs. It fosters the pursuit of collaborative solutions that align better with community values and offer longer-term utility. Moreover, these practices enable the creation of a pipeline of gray and nature-based infrastructure projects.

“Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough, I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower, attributed

3. Aggregate high-quality gray and green projects into a regional and/or state-level infrastructure pipeline through which capital can be efficiently attracted, integrated, and deployed.

This creates a market for change. Scale matters when it comes to infrastructure and small towns have poor economies of scale. A birds-eye view of investment needs can stimulate additional innovations like the bundling of small projects to ease administrative burdens or otherwise level the playing field for those towns that cannot compete under existing conditions.

These inter-dependent activities, in their own ways, make the problems even bigger and as a result can unlock opportunities that today are fractured. The lessons learned, and information gained, can mobilize and harmonize scores of organizations, including those that seek to bring conservation and nature-based solutions to scale; focus on social and environmental justice and public health; and develop new private and public-private infrastructure financing schemas. It’s a win/win when we align public, civic, and private institutions to reward collaboration, co-production, and creativity.

The scale of our environmental and municipal water infrastructure challenges are immense, but so are the opportunities. Over $1 trillion is needed over the next 25 years to fix, replace, and expand our country’s drinking-, waste-, and storm- water systems. Capital investment of this magnitude will make a difference one way or the other, but if done right, it will set us on a more sustainable path for people, wildlife, and biodiversity.

Doing it right means reimagining the problem space whereby nature and the most vulnerable among us are at its heart in order to release the problem-solving ingenuity that exists in all communities. Only when a resilient water future is a viable option for the smallest and most economically disadvantaged towns, will it be an option for all communities. It starts upstream.