The Water Framework Directive

European water policy aims to ensure that we have enough good-quality water for all our needs and in the environment. EurEau shares this goal in representing Europe’s national associations of drinking water and wastewater operators.

What’s next for Europe’s water

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is the overarching piece of legislation which came into force in 2000 to protect the quality and quantity of water resources across Europe. It was – and still is – an innovative piece of legislation, which introduced the principle of integrated river basin management across international and national boundaries.

We need the correct implementation of EU law to ensure that domestic consumers do not pay extra to keep our water safe and clean.

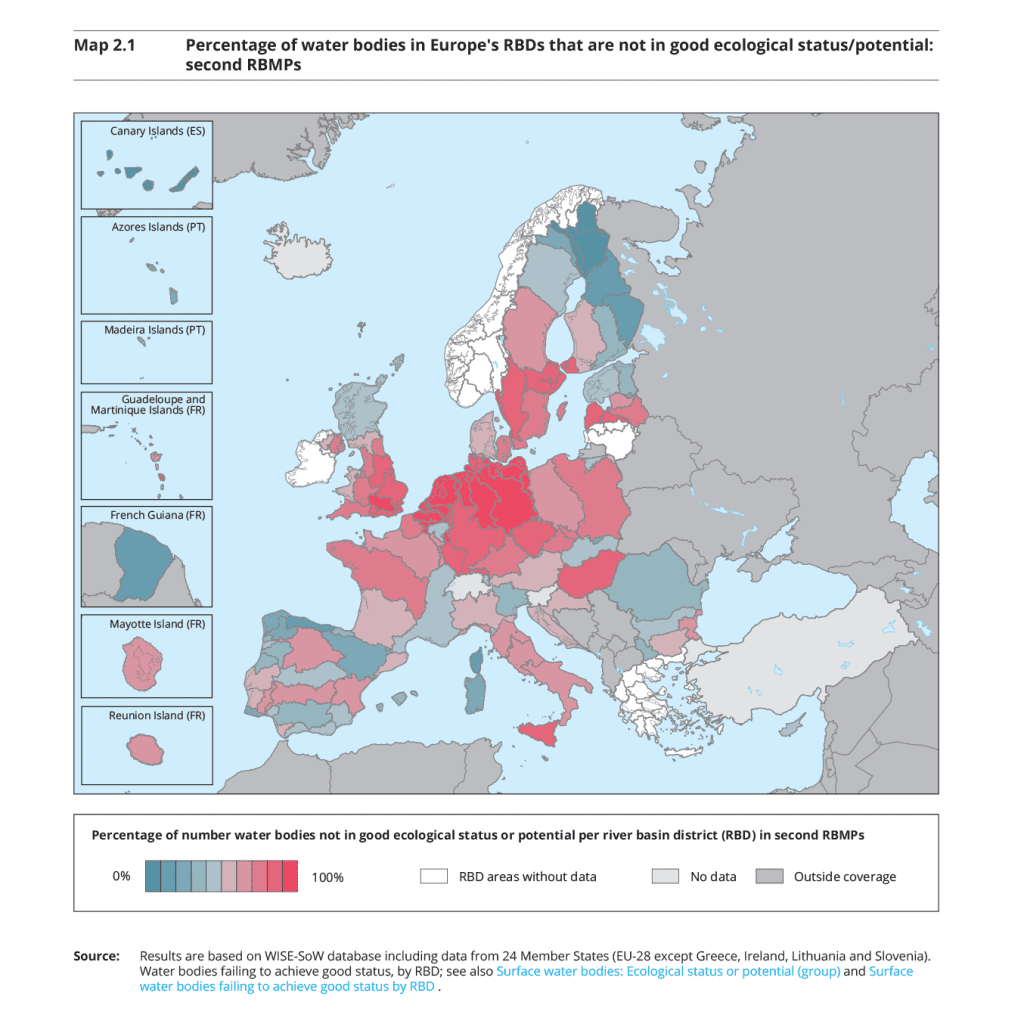

EU Member States must publish river basin management plans (RBMPs) on how they achieve the WFD environmental objectives. The European Commission published the study on the second RBMP cycle in December 2018.

According to the European Environment Agency’s ‘European Waters’ 2018 report, 74% of Europe’s groundwater achieves good chemical status, while 89% of the groundwater area achieved good quantitative status. Around 40% of surface waters are in good ecological status or potential, and only 38% are in good chemical status. In many cases, a few priority substances account for poor chemical status, the most common being mercury.

Since its entry into force, the WFD has shown slow, but steady, improvements, but we did not achieve the goals of “good status” for water bodies by 2015 nor did we prevent any further deterioration of our water resources. There are several reasons why this is so, including the challenges of climate change, emerging pollutants, and large-scale projects like waste water treatment plants that take years to plan, approve and build and that play an essential role in meeting WFD targets.

Applying the source control principle

Whatever the reasons for not meeting the WFD goals in time, the lack of effective implementation of the source control principle in the EU can be considered as the root cause. Source control prevents contaminants from entering the water cycle in the first place; it is much easier – and cheaper – to limit pollution at the source, especially so that consumers do not have to bear the costs of further end-of-pipe treatments. At the same time, the Control at Source Principle allows for the development of a truly circular economy, as it will be easier to recover nutrients and reuse treated waste water.

We all have a role to play in this, from water operators to policy-makers to water users at all levels. Implementing the Control at Source Principle through strong legislation is a brave step and will require strong commitment and action from powerful industrial groups. We are pleased that the European Commission uses control at source measures in its Plastics Strategy and, related to this, the Single Use Plastics Directive proposal. The EU executive also promises to deliver ‘soon’ the Strategic Approach to Pharmaceuticals in the Environment and a Strategy Towards a non-toxic Environment – both of which are likely to look at control at source measures as part of the full value chain.

Europe does not need to be reluctant. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union clearly enshrines the Polluter Pays, Control at Source and Precautionary Principles as basic building blocks of EU environmental legislation. Logically, these principles need to be included in EU law and effectively implemented at Member State level. And we need greater policy coordination between the WFD and other EU water and environmental legislation, such as the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD), the Drinking Water Directive, and the Bathing Water Directive. Sectoral policies such as agricultural, climate and pharmaceutical policies can also be better aligned to ensure that we are all reducing pollution and its effects on receiving waters.

For example, looking at nitrate pollution of drinking water resources. Several European laws refer to the threshold value of 50mg/l: the Nitrates Directive, the Groundwater Directive, the Drinking Water Directive and even the proposed Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Still, the threshold value is exceeded in numerous drinking water sources, with financial consequences for water consumers. In theory, the newly proposed CAP makes payments to farmers conditional on them adhering to the Nitrates Directive. In practice, this link is likely to be too weak to solve this problem.

The Control at Source Principle allows for the development of a truly circular economy.

The EU is now reviewing a lot of its water policies. It is possible that the WFD and the UWWTD will be updated over the next five years. These reviews present a wonderful opportunity for the EU to upgrade its policy coordination with the aim of protecting our water resources for the next generations.

A common tool for implementation

The objective of all European water bodies reaching ‘good status’ by 2015 was not achieved, and all parties agree that it will not be met by 2027 either, despite increased efforts. EurEau believes that to meet the challenges of climate change and emerging pollutants to name a couple, as well as the objective of the original WFD to conserve our water resources, the ambition of the WFD should be maintained also after 2027.

The assessment of the status of water bodies, as described in Annex V of the WFD, is based on the one-out-all-out principle. This system monitors the status of all water bodies across Europe in their path to reach the ‘good status’ and it should not be fundamentally changed.

There is no alternative to healthy and clean water that benefits both humans and nature.

However, the classification system describes all the elements to be met when assessing status for surface waters and groundwater. If one fails, the ‘good status’ is automatically not achieved. This approach masks and distorts the reality of the water body quality since it provides only a snapshot of its ‘status’ and focuses the attention on the lowest quality elements. The result is that trends and changes over time are not shown. This makes it difficult for authorities to show the improvement of the quality of water bodies and justify the investments made and those needed in the future.

There should be a commonly agreed additional tool for Member States to show improvements, such as a set of biological or chemical parameters assessed over time (some microbiological parameters are already included in the Bathing Water Directive). At the same time, hydromorphological or quantitative status could be looked at on their own. This will clarify which sectors are successfully contributing to the improvement of water bodies and to what extent investments are producing positive outcomes.

An undulating landscape

Member States cannot keep using investment costs as an excuse as to why they are not meeting the WFD requirements. While we recognise and accept that countries have different circumstances, the protection of water resources is paramount for sustainable development and for protecting public health.

The European Commission and Member States should carry out a critical analysis of why the objectives have not been reached. Improving water quality should be a continuous process; it is important to maintain the current level of ambition without changing the general WFD objectives, while an extension of the deadline beyond 2027 could be considered when evaluating compliance.

Maintain the current level of ambition without changing the general WFD objectives.

The WFD can develop a rolling system further under which Member States produce multi-cycle plans to contextualise improvements anticipated in individual cycles and provide the relevant “within-Plan” milestones. This approach would also help to ensure that appropriate monitoring is identified and introduced at the right time.

Whenever timescales are extended, it must be remembered that the principle of ‘no deterioration’ continues to apply. This concept itself needs to be analysed according to those changes that are population driven, and those that relate to changing natural conditions, including climate.

From a water services point of view, exemptions that lower the ambitions towards achieving ‘good status’ should be avoided as much as possible. We should be working towards developing in line with the overall ambition of sustainability.

The environmental objectives of the WFD are ambitious and should be maintained. Many improvements have taken place but the lack of a holistic approach to water pollution has increasingly led to unsustainable end-of-pipe solutions rather than more viable source control measures, making the burden of investment fall on consumers through their water bills. This situation should result in a sound and transparent public debate.

Speaking of investment, the WFD lays down the principle of cost recovery for water services. Water infrastructure in many parts of Europe is ageing due to a lack of investment. The price we pay for our water should include depreciation, renewal and maintenance costs, as well as the cost of financing long-term investment, so that the costs of supplying clean and safe water are shared between current and future generations in a sustainable way.

We are aware that some stakeholders would like to lower the goals of the WFD in a potential revision. We call on policy-makers to resist this pressure and continue the engagement of all actors within the Common Implementation Strategy of the WFD. There is no alternative to healthy and clean water that benefits humans and nature: all sectors should take their responsibilities and show engagement and ownership.