Machoi and the Sound of Meltwater

Nothing will stop the melting of the glaciers on display as the last remnants of the Ice Age.

The origins of the chinar tree

The chinar (Platanus orientalis) is said to have come from Persia during the 14th century when the Sufi saint Sayed Sharf al-Din, aka ‘Bulbul Shah,’ came to Kashmir to spread Islam. He was accompanied by traders and merchants who brought chinar seeds along with other spices and goods to barter and sell. Sayed Sharf al-Din is famous for having converted the reigning Buddhist ruler of Kashmir, Rinchan Shah (1320–23 AD), to Islam, who in turn dedicated the first khanqah (shrine) in Kashmir to Bulbul Shah. ‘Bulbul’ is the ‘hoopoe’ bird and a reference to Sufi mysticism’s famous hoopoe that led the Conference of the Birds by Farid al-Din Ibn ‘Attar to the highest possible spiritual realms. The Sufi Shah is said to have sat and meditated for so long that the hoopoe built a nest on his turban, hence his nickname: Bulbul Shah. The Khanqah Bulbul Shah is one of 15 Heritage Ghats (steps leading down to a river or lake) to be renovated in 2023 as part of the Jhelum Riverfront Project. The Bulbul Shah shrine is located in Sheher e Khas on a northern bend of the Jhelum River; common eagle kites perch on its green rooftop and swoop down over the steps when they spot a fish in the waters of the murky Jhelum River. In Kashmir, Chinar Day is now celebrated on 15 March.

Driving to the glacier

Heading north out of Srinagar, a long row of thick-trunked chinar trees, each several hundred years old, lines an asphalt road with no lanes. The chinars cast long morning shadows towards the west, across the edge of wide rice fields. Their big hand-shaped leaves turn red, then brown, in the autumn, like the Canadian maple. On the outskirts of Srinagar, swaying green rice paddies cover the valley floor. Rice is the main cash crop that farmers cultivate by hand; in the spring, they pick the rice and dry the grains on the side of the road on large canvases. The warmth of the sun steams off the moisture emitted from the grains that the farmers also turn and poke at with sticks to air out. They can either sell their produce to people driving by or roll up the tarps and sell in bulk at a lower price to a middleman who will take the rice to market. In this early morning of mid-September, the fresh sunrays coming across the mountains now catch the tips of the rice stalks, casting a golden glow across the valley.

All the shops are closed along the street towns. Stray dogs stretch but mostly sleep in the shade. Some Indian soldiers are standing guard behind sandbags on the road. Then some other guys in civilian clothes emerge from a shack by the road and open a metal barrier. They give the Showkat driver a blue toll ticket stub and get 100 INR in return for the right of passage through the town of Gandelpur. “Bismillah (In the name of God)”, the Showkat says for the tenth time since you set out from Srinagar. Bismillah is the Islamic invocation for having God-Allah on your side when carrying out an activity, in this case, the activity is driving the +100 kilometres to the Machoi glacier in neighbouring Ladakh. You drive past an ominous blue Center Reserve Police Force (CRPF) truck that sits idly at the entrance of Ganderbal: all the shops here are closed and the streets are empty. Showkat means ‘dignity’ and ‘intensity’ in Urdu; it’s going to be an intense ride through the Zojila Pass.

Up ahead on the road, puppies appear to be playing, going back and forth from their mother on the side of the road to a puppy lying on its side with a red splotch where its head used to be in the middle of the road. Showkat swerves to the left and repeats “bismillah” again, then passes more roadside shops with closed shutters, empty stalls, and the occasional car or motorbike. All along the way, Indian soldiers stand loitering, walking with automatic rifles, new camouflage uniforms, and padded turban-like helmets. This is the most militarised area in the world with some 9 lakhs worth of Indian soldiers. One lakh equals 100,000 units, so the Indian Army presence is somewhere around 900,000 soldiers patrolling the streets with no lanes that connect the towns of Jammu and Kashmir (not to mention what happens in the rural countryside areas that are more off limits).

This is the most militarised area in the world with some 9 lakhs worth of Indian soldiers.

Apart from the blue CRPF armoured vehicles, there are the Border Security Force (BSF), the Special Task Force (STF), the Special Operation Police (SOP), the Jammu Kashmir Police (JKP) and other minor units that make up this motley of security forces that would give any conflict resolution analyst a tremendous headache in figuring out how to do any security sector reform (SSR). Imagine trying to do disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) here where these acronyms become vacuous clip-phrases for arm-chair pundits to pontificate about geopolitical solutions that do not exist today. Above it all is the Indian Army – the ‘omni-presents’ as some locals call the sorry-looking soldiers – standing guard all along the roads and deciding when to open or close the treacherous Zojila Pass connecting Kashmir and Ladakh (no guard rails here). You pass some cars and the flutter of a pink scarf of a woman sitting sideways on the back of a motorbike – no helmet, thick black braid, holding a toddler against the back of a man with a weathered face squinting into the wind.

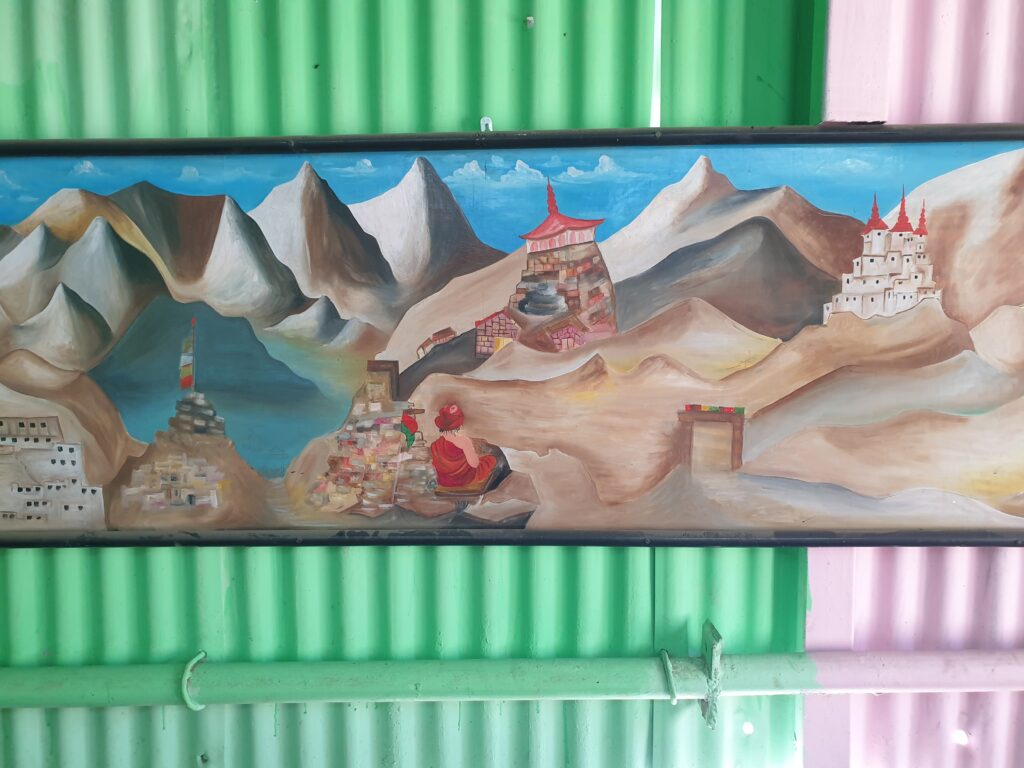

The road goes along the Sind River that starts to climb out of the valley. In the distance, military encampments and a new road are being built with tunnels going towards the Yathras Hindu shrine located in the Amarnath Koi (caves) in the Himalayas between the Machoi and Kolahoi glaciers. This is a new tourist destination for Hindus to visit some caves, trek, see the stalactites, and learn something about the Himalayas. New Hindu tourism has flourished since the abrogation of Article 370 in December 2021, officially making Jammu and Kashmir a‘Union Territory’ (UT) of India. In principle, tourism can be great for the local economy if it actually gets to the locals and if it respects the environment as much as possible. Here, the new road to Amarnath has a blatant impact on the natural landscape: new roads cutting across the land and new encampments for military and tourists alike have sprouted up like white square mushrooms with green tin rooftops along the silver Sind River.

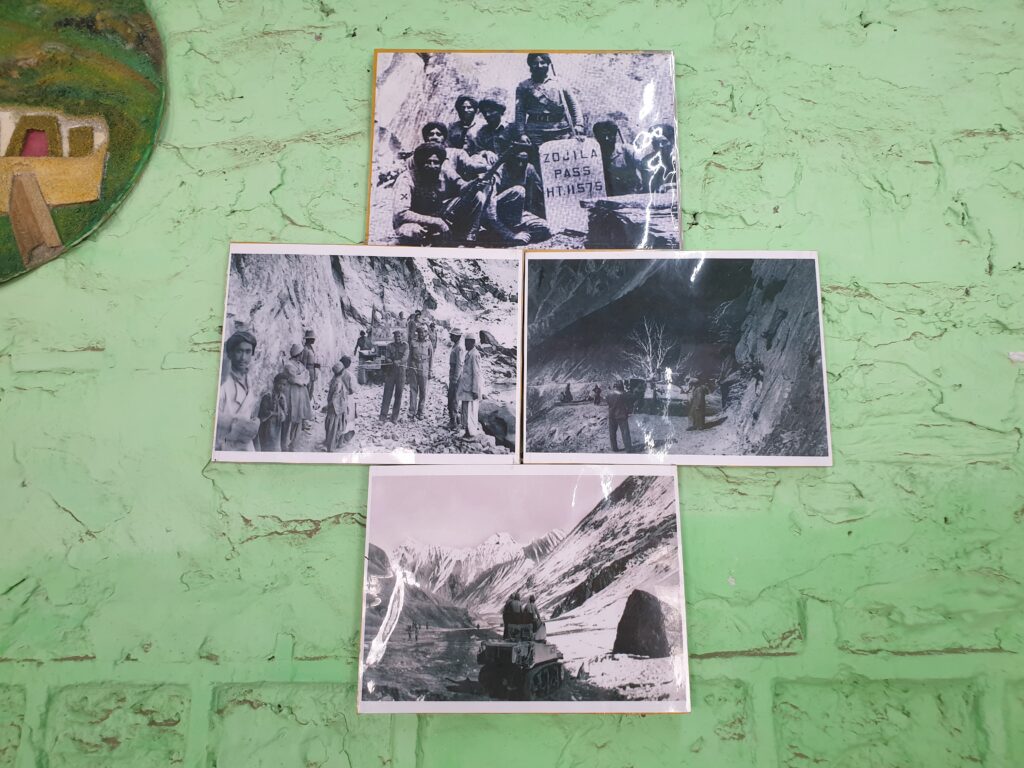

And then the Zojila Pass starts to climb: a muddy two-way road cut into the side of the steep mountains where attempts to pave it with cement bricks have flattened the road here and there but otherwise failed to overcome the mud and potholes. There are no guardrails on the edges; the precipice drops hundreds of metres straight down. Vehicles often slide off the edge, Showk says after the fact over lunch later in the afternoon, but ignorance is bliss at the moment, dignity reigns over fear, and you continue bumping along the pass, behind colourful trucks carrying cargo of sheep, vegetables, furniture, and other goods hidden in the metal hatchbacks. A military convoy of maybe 20 or 30 army trucks with tarps flapping passes in the other direction, coming back from the Siachen glacier basecamp located in the Karakoram Range on the Indian side of the Indo-Chinese border, where tensions run high over control of the hydropower being harnessed from these splendid glaciers. Then, cars pass each other on the outer edge of the precipitous pass, skidding, beeping, and speeding around the massive military vehicles carrying covered tanks to the front with China.

In the denser winter months of December to March, the Zojila Pass is closed due to weather conditions: up to 10 feet of snow makes the road unpassable for any sort of vehicle. Regardless of the weather, the Indian military can also decide to close the pass for any given ‘security’ reason. There is road work ongoing on either side too: on the mountain side of the pass, gangs of workmen dig a trench-like gutter with picks and shovels for rainwater and snowmelt to flow, as well as to stop the small debris that falls down the mountain side. On the cliffside, other groups of men fix the edge with dirt, cement, and stones – with no ropes or helmets or any kind of insurance or safety measures. These guys make about 500 INR ($5) a day. They come from nearby villages. Rugged and hardened men, some take a break and sit on the edge, unphased by the sheer drop of the precipice, smoking and looking across the gorge at the mountains that fold in sharp shades of deep green and grey that ascend to a jagged ridge silhouetted against the bright blue sky.

The location of Machoi Glacier

There are approximately 15,000 glaciers in the Himalayas, providing water for the great rivers of the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra, which in turn provide water to about half a billion people in South Asia. Located on the Tibetan Plateau, the Machoi Glacier is situated in the Indian State of Ladakh and is the source of the Sind River that flows westwards towards Srinagar, Kashmir, and of the Dras River that flows eastwards towards Kargil, Ladakh. The Machoi Peak is at 5,458 metres altitude. Due to increased temperatures over the past 50 years (1970–2025), Machoi Glacier has receded by approximately 30%. The glacier retreat between 2000 and 2010 is attributed to increased precipitation that accelerates the melting due to less snow cover. The University of Kashmir is researching over 5,000 other glaciers suffering a similar predicament. Coupled with increased anthropogenic activity, this prototypical warming scenario is also due to the deposition of light-absorbing impurities in the glacier ice that induce changes in the distribution and development of new cryoconite holes on the glacier that result in enhanced glacier melt.

Walking on water

At the roadside pitstop of Gumri, you get some sugar with water, called ‘tea’, and a samosa. There is a memorial for a battle won by the Indian Army that tourists visit. A herd of hundreds of sheep is comes up from the river, crossing the deserted brown plain and impeding the cars and trucks from moving along the road. They bleep and walk along, swatted by herders that occasionally whistle or shout something to keep them going in the general direction of the alpine grass on the other side of the road. The vegetation has changed drastically from the lush evergreen of Kashmir to the brownish grey of Ladakh. The temperature is substantially cooler here. You are on the Tibetan Plateau now – this strange barren territory +3,500 metres above sea level, contested with China: the Aksai Chin portion was given to China during the 1947 Partition by Pakistan who would not have been able to control that piece of eastern desert lands while also holding onto Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK), so many Kashmiris still see Aksai Chin as part of historic Kashmir, which adds another piece to the geopolitical puzzle.

At the base of the Machoi glacier, some metering devices measure the water flow and temperature of the stream. On the other side of the stream is a nomad encampment of sheepherders. Their white tent is held down with big stones against the strong winds. Looking back down from the rocky path, you see the yellow tent getting smaller and the stones placed in a circle where other tents have been. A few generations ago, the Machoi glacier filled this gorge, reaching down to the base of the mountain where you imagine the nomads would chip at the ice to make fresh drinking water in the evening or use it for washing and cleaning. Now, the glacier has receded halfway up the mountain, retreating 30 metres per year, maybe faster. It is astounding to see how fast a glacier melts: within a couple of weeks in the summer of 2024 (from 12 August to 5 September), an ice bridge connecting the fragmenting pieces of the glacier crumbled and was carried away by the meltwater from the snowmelt and the remaining glacier above.

It is astounding to see how fast a glacier melts: within a couple of weeks in the summer of 2024.

Walking next to the glacier, you notice and learn the difference between snowpack and ice, both of which are melting as you look up at the mountain. Snowpack is perennial and melts faster, being exposed more directly to the sun. Glaciers are less exposed to the sun because they are usually covered in snow and are supposedly more permanent. Near the peaks, there is fresh snow that has fallen, filling the sharp folds and bowl with pristine blinding whiteness. Then there is a shiny black spot that is vertical rock where the snow cannot stick, almost like a sore black hole in the snow, a secret entrance to the mountain. Further down, you step onto sandy ground and without knowing it at first, you are standing on the glacier. This is a debris glacier: where dirt, pebbles, and stones from the mountainside have crumbled onto the ice forming a layer of grey ground. You crouch down, brush the dirt away, and touch the ice, clear and transparent, going deep into the darkness. You wipe away more dirt: the ice is a translucent black and wet on the surface, melting slowly on the top layer as well.

It’s a very unsettling feeling to look into translucent black ice, almost as if the mountain were peering back at you with invisible eyes, transmitting a dark foreboding presence. The rest of the glacier extends up the mountainside as far as the eye can see like some big blue whale sleeping or waiting for the rain to slip and slide down to the river and eventually to the ocean…which is where all glaciers end up. You learn about glacier ‘surges’ and how they can move a few kilometres per year, much faster than the usual 10 to 15 metres per year. Surges can cause glacial lakes to form and accumulate vast amounts of water. Glacial lakes can in turn overflow and cause devastating tsunami-like floods when their banks break. Surges occur in cycles of 14 to 15 years and are unrelated to climate change and rising temperatures. The cryosphere (snow, ice, permafrost) interacts with the atmosphere and hydrosphere which also connect with each other. All water flows downhill but all sublimation, evaporation, and evapotranspiration also ascend in particles to the sky, coalescing in clouds and falling as snow or rain again to the mountains and trees. When you touch the smooth black ice, you can perceive the patience and purpose of this great cycle.

The cryosphere (snow, ice, permafrost) interacts with the atmosphere and hydrosphere which also connect with each other.

And walking on water, the ice melting irrevocably beneath your feet, invisible streams carving paths beneath the remaining ice, melting occurs from beneath too. Where the ice meets the rock of the mountain, is where the fastest melting occurs due to the temperature difference between the earth and the ice: the warmer the earth, the faster the melt. This is where moraines appear: anywhere that used to be covered in glacier ice. Moraines are the visible memory of the mountain – geological proof of the previous presence of these great chunks of living ice.

You come upon a meltwater stream that is gushing down, creating a rushing sound of white noise; the stream is exposed and visible now beneath a patch of dripping ice. The meltwater emits a continuous soft roar like fire burning, and the smaller, almost imperceptible sound of drops of water falling from the overhanging lip of the ice onto the wet ground, like a little ‘tap, tap, tap’ of rain from a gutter. Dripping water and gushing streams you watch as the meltwater disappears under the ice, gradually taking more particles of ice with it, digging wider passageways, bigger tunnels, carving out larger crevasses in the rock of the mountain, thus creating rivers, except that here the replenishing of water is not happening. The cryosphere-atmosphere-hydrosphere cycle is out of sync.

On the surface of the glacier, many smaller streams come down the mountainside too, from the snowpack primarily, but also from the melting effect caused by the dirt and pebbles. The little streams are very cold when you drink from them, so cold the milky grayish water stings your face and numbs your skin, and little particles of sand remain on your fingers. Where the top of the ice has melted a few centimetres and mixed with the dirt, it has created a greyish sludge that moves when you walk on the muddy surface. You pick up a few pebbles and rub the sand from the grey and yellow markings. It is not sulfur, nor is it flint or gold. You will find out and slip the little rocks into your pockets as mementoes from Machoi.

It is estranging to walk on a glacier, this living organism that must have some sort of emotion like other organic entities. Due to the motion of the glaciers, they must have a form of emotion, a sensory tactile induced feeling that makes them move. In some softer parts, the ground gives and sinks with your steps, like sand at low tide, seeping in slightly you imagine the entire hollow vault beneath you giving way as you fall into the meltwater stream moving down towards the river in the valley. You will not die at first from the fall: somehow miraculously you avoid the rocks and the rapids carry you tumbling down the stream to where it levels out and you step out of the freezing grey water that has got into your bones; you will die of hypothermia and pneumonia a few days later from the shock of the cold; or you will live to tell the tale of the blue whale that woke and slid down the mountain with you riding on its back to the distant ocean. The air is thinner up here; you are a bit delirious. Imagine making it to Mount Everest at twice this altitude. You are only at 3,750 metres altitude now. You take long deep breaths to clear your head. You are winded and find a bigger rock to sit and rest.

Far down below some micro-machine vehicles are moving along the road. You follow the massive cloud shadows across the flat silver riverand up the steep brown mountains ascending across the valley. Behind the Machoi glacier are the Amaranth caves and Kolahoi – the highest peak in Kashmir – where devastating hydropower projects have been underway in attempts to harness the tremendous flow of the meltwater. In 2022 (8 July), flash floods swept through a campsite near the holy Amarnath Cave, killing at least 16 people, with dozens injured and others missing.

In June 2021, a flash flood occurred in Uttarakhand due to the collapse of a rock-ice avalanche (26 million cubic metres) from the steep Ronri peak. The steepness of the cliff, combined with water in the impact zone, converted most of the ice into water. The mix of snow, ice, rock fragments, and soil created a massive slurry (debris flow) that destroyed the twin hydropower dams of Rishiganga and Tapovan like dominos. What goes around comes around: the human-induced emissions caused temperature rises that caused more melting which caused flash flooding that destroyed the infrastructure built by humans to harness the power of water, which was supposed to help reduce the human-induced emissions. What an absurd cycle.

Sitting on what remains of this glacier – one of 15,000 glaciers mapped in the historic Jammu and Kashmir region – it is hard to feel like nature is not on display. In all its raw beauty, its shameless nakedness, this is nature changing its clothes before everyone’s eyes. In front of everyone who wants to watch, the demise of the glaciers is becoming a tourist attraction. “See the glaciers before they disappear!” the headlines will read. “Touch the ice before it melts!” others will say. There is no glass casing to be put over this mountain, as the analogy goes, for the National Parks in the United States of America, where Indigenous populations are not allowed to resettle their lands. There, the glass casing analogy was imposed as part of the ‘nature conservation’ movement to preserve the environment as best as possible, at the demise of the Indigenous people who may have lived in harmony with that very same environment.

Here, there is just the sun and the wind and the red heather on the mountain side and the sheep-herders down by the river in the valley and the constant dripping and gushing of the melting glaciers that are irrevocably retreating. Some real-time cameras will be installed to record and transmit the inevitable death of a glacier, brought to you live from Ladakh by Indian national television or National Geographic. Sensors will be plugged into the riverbanks, into the permafrost, into the streams and the mountains to take measurements of what is happening, to proclaim a better understanding of what will come to be when the glaciers will no longer be. The real-time video will be boring to watch, because it seems so slow from afar, but up close in real life the pace is so fast.

Why the cryosphere matters

The cryosphere refers to the portions of the Earth’s surface where water is in solid form. This includes snow, glaciers, ice, sea ice, ice sheets, ice on rivers and lakes, and frozen ground and permafrost. The cryosphere comprises about 10% of the Earth’s surface but is decreasing with rising temperature due to global warming. The cryosphere is intricately linked to the atmosphere (air), hydrosphere (water), lithosphere (rock crust), and biosphere (ecosphere). Solar radiation and the greenhouse gas effect are increasing the sublimation of snow and ice from the mountains and glaciers, while increasing evaporation and evapotranspiration from lakes, rivers, and forests. The thawing of the different kinds of permafrost (continuous, discontinuous, and sporadic) also releases methane from the ground and other aerosol particles that contribute to the global greenhouse effect of retaining heat that increases global warming. Melting glaciers means more water in streams, rivers, and glacial lakes, and this increases the risk of glacial lake outbursts and flash flooding that are already occurring in mountainous regions. The natural cycle of the five interrelated ‘spheres’ of our planetary climate system is unhinged and causing unprecedented altercations that have unknown effects, except the certainty that there will be no more glaciers. Learn more about the interactions between the cryosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere with the CryoSCOPE Project.

Returning to Srinagar

Geology does not care. Rocks have no feelings. The moraine sedimentation line left on the side of the mountain shows where the glacier once was and carries a different notion of time that humans can measure but not comprehend. The rock formations and fragments of crumbling stone testify to something eternal beyond the grasp of what humans want to control. There is no going back. There is no proverbial ‘return to nature’. The glacier will not grow back and fill this gorge again. Now, the orange-marbled rocks are exposed showing their bright splotches and long streaks down the smooth wet surface. The lichen is breathing blue, green, and turquoise on the side of the mountain on the large stones beneath the carpet of little red alpine flowers that cling to the earth. Crouch down and see their short stems swaying in the wind; up close the auburn-tinged colour is actually a bright pink, white, and red. Silver flint speckles the ground, shining brightly, as if reflecting the water of the river below, flowing silently, bouncing playfully over rocks.

You pass Zero Point, that point of inflexion where the water goes towards Kargil, Ladakh, or the Sind River towards Srinagar, Kashmir. You follow the Sind River down now to the treacherous Zojila Pass, in the other direction this time. The passenger seat on the left (British colonialism still at the wheel on the right) and cars to the left, so you are on the edge of the precipice, looking at your life go by before your eyes, thanking God for the time you have had on this Earth, leaning so far to the right in your seat away from the open window that the driver laughs and says ‘bismillah’ and hums a religious tune about Allah and how everything is preordained and if we go today on this pass as we could have gone on that glacier, it is out of our hands – we are just mere mortals stumbling along generally making a mess of things.

You snap some photos of the gorge below rather blindly, trusting your smartphone will see what you want to see but can’t bring yourself to look at. You glance at the workmen toiling away and sitting as if it were completely normal to be on the edge of a precipice. The steep folded brown and gradual green of the mountains appear and disappear as you start the harrowing hairpin descent. You look towards the mountains and a dragonfly appears outside the window, hovering like a mini helicopter and then darting away, only to be replaced by a pair of crows flying high, soaring on the upward winds coming from the valley below. What a feeling that must be: to catch and float around on the winds carried by invisible waves. Another cliff curve and you see the vehicle going straight off the edge into the emptiness, floating for a few seconds and then dropping without a parachute down the precipice, crashing and crumbling on the rocks below. You decide to focus on the trucks coming up the hill.

With every acceleration, the colourful trucks emit big clouds of black smoke. There is no point really in closing the windows. The trucks are painted yellow and pink, red and brown, and blue and green too. They are mostly TATA and Ashok Leyland trucks. The one with the big yellow moustache on the metal motor grate signifies that they are Sikhs. There is a big yellow moustache coming up the hill with ‘SELFISH QUEEN’ written in pink on its front bumper. Then another truck that reads above the windshield: ‘MUSLIM FOREVER’ and below on the blue bumper: BADASS. Another says: “Life is one time offer use it well.” Good words of wisdom. Another truck rumbles up the hill: “The greatest pleasure in life is love.” And “Panga is not changa.” And then the sobering bumper: [blank white paint] Innocent Killing in My [blank white paint]. The authorities make drivers paint over the ‘Stop’ and ‘Kashmir’ of this message.

The mountain peaks are shrouded in misty clouds, adding to the lure of mysticism in this land. A horse plods along down the road by itself, there are no cars around, no owner, no trucks, just a brown horse with its black mane bent down, head looking at the ground ahead of its front hooves. The painting could be called: “horse plodding down a terrifying pass.” Big drops of rain splatter like snowflakes on the dusty windshield, covering the glass in a constellation of white fractal flowers. Finally, Showkat activates the windshield wipers, clears the view, and the rain has passed. It is past 3:00 pm and the workers are done for the day; they clamber into the back of dump trucks and barrel down the mountain road, avoiding a dirty-white haggard horse coming straight up the road, honking and swerving to avoid the skinny brown cows with bloated bellies, back down to the plains they race where they jump off at their village stop or the main junction where another CRPF patrol stands guard somewhat lethargically, looking around loitering – what a life.

Past construction sites and following a cement truck now. Iron rods by the side of the road. Metal junkyards. Then the rapids of the Sind River cascade playfully, powerfully over the rocks down below to the side of the road. Then individual homes and clusters of people (villagers and farmers) move slowly in the afternoon fields across the river. The evergreen forest ascends and covers the hills of Kashmir. Entering another small town, a sign on the side of a public latrine, next to a cricket field where a game is ongoing, reads a little rhyme:

Every Indian must be aware

and stop littering everywhere.

More Indian soldiers are in the roadside towns that are open now. There are fruit and vegetable stands beside the road, selling apples, bananas, carrots, and long green squash. The shops are open too, the ‘market’ of each little village-town is bustling with carts, vendors, and buyers, people walking around, others sitting staring from their stalls. Sandbags around a military checkpoint. Another blue CRPF armoured vehicle standing by, ready if needed. Local elections are coming this month. The main mosque of Srinagar will be closed on Fridays. There will be a tussle in a street of the city around a BJP politician with JKP security guys in camouflage and automatic rifles. It’s just the media making much ado about nothing for a politician that no one knows here.

Past the same military points again. This time you notice pairs of beer and whiskey bottles hanging from barbed wire outside a military compound. You do not search or ask for the meaning of this display of wantonness. This must be a miserable existence for the soldiers too. What a horrible existence it must be for Indian soldiers to be stationed in Kashmir, making a pittance, far from their families and from understanding what they are really doing here. Kashmir is about 80% Sunni Muslim, 10% Shia, and the rest a mix of Pandit (Hindu), Christian, and Tibetan. A woman wearing a green gown and pink shawl walks along the road carrying a large pan of cow-dung patties on her head to dry and burn for heating and cooking.

Cars honk and swerve around a man in the middle of the road ahead: he is standing with a long stick, swinging and jabbing at the big branches of a large walnut tree overhanging the strip of unmarked broken asphalt; a small boy – his son, apprentice, or both – crouches by the side of the road with a little green plastic bucket, awaiting orders to run out and collect the fallen nuts that have a bitter taste and look like little brains when you crack open the hard shell. You think of the dead puppy from this morning. Walnuts look like little brains. Walnut fudge is famous here and these walnut pastries are offered as presents when couples get engaged.

Another rustic scene: two men are cutting a big log with a rusted two-handled saw, like some realist painting from a previous time, they row back and forth in rhythm with another guy sitting on the log to give some leverage, or maybe he is just watching or waiting his turn. They seem to be enjoying the activity by the side of the road. Further ahead, there is the smell of sawdust and the sanding of wood from an open-air furniture shop making window frames for houses (brick walls, wooden window frames, and tin roofs dominate the Kashmiri architectural style).

Then, hordes of children along the roads in school uniforms and herds of sheep clog the lanes as they are shepherded off the road. Horses, cows, sheep, and goats graze together in the fields by the river. Three young women walk along the road, two wear niqabs and the third frowns and raises her hand quickly to hide her face as you drive past. You see a line of black birds on the green tin rooftop of a red brick building on the northern outskirts of Srinagar. They just sit looking out across the silver Sind River at the pine evergreen hills of Kashmir. The rice fields appear in the flatlands of the valley, and you enter the long row of old chinar trees.

Srinagar, 5-7 September 2024, 7-14 March 2025