The Hidden Costs of Military Expansion on Climate

Military activity: A yawning gap in emissions reporting with dire consequences

Five months have already passed since the onset of Israel’s war in Gaza and the death toll is higher than any other conflict of the 21st century. The devastation is unprecedented. People risk their lives even to get some flour for their families, and the means used for this social and environmental degradation lead to greater food and infrastructural insecurity, and climate impacts – and unveil consequences of military activity beyond the local.

The destruction of infrastructure and loss of human lives are worrisome, but the movement of troops – from training, transportation, and deployment – already has dire consequences for the environment.

On top of that, military institutions have today the privilege to intensify greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions without accounting for them to the United Nations’ climate body, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Knowledge gap in emissions reporting

It all began with the 1997 Kyoto Protocol negotiations. During this time, the US government successfully lobbied for an exemption for its military-industrial complex from any emissions-cutting obligations. This exemption remained in effect until the 2015 Paris Agreement, which addressed and eliminated this unjust policy. However, to this day, countries are still only required to voluntarily report their national military emissions.

The result is that the biggest investor in the military, the US, is not obliged to do a full emissions reporting, causing a very significant data gap. However, even if military emissions reporting becomes obligatory, it will be applied to only 43 Annex I countries, excluding nations with high military activity, such as Israel, Saudi Arabia, and China. These states are not obliged to report any of their national emissions to the UNFCCC. On the other hand, nations that report their military emissions, such as aircraft and land vehicles, can still leave out emissions that greatly contribute to the climate crisis, including military equipment procurement and other supply chains.

Skyrocketing military emissions

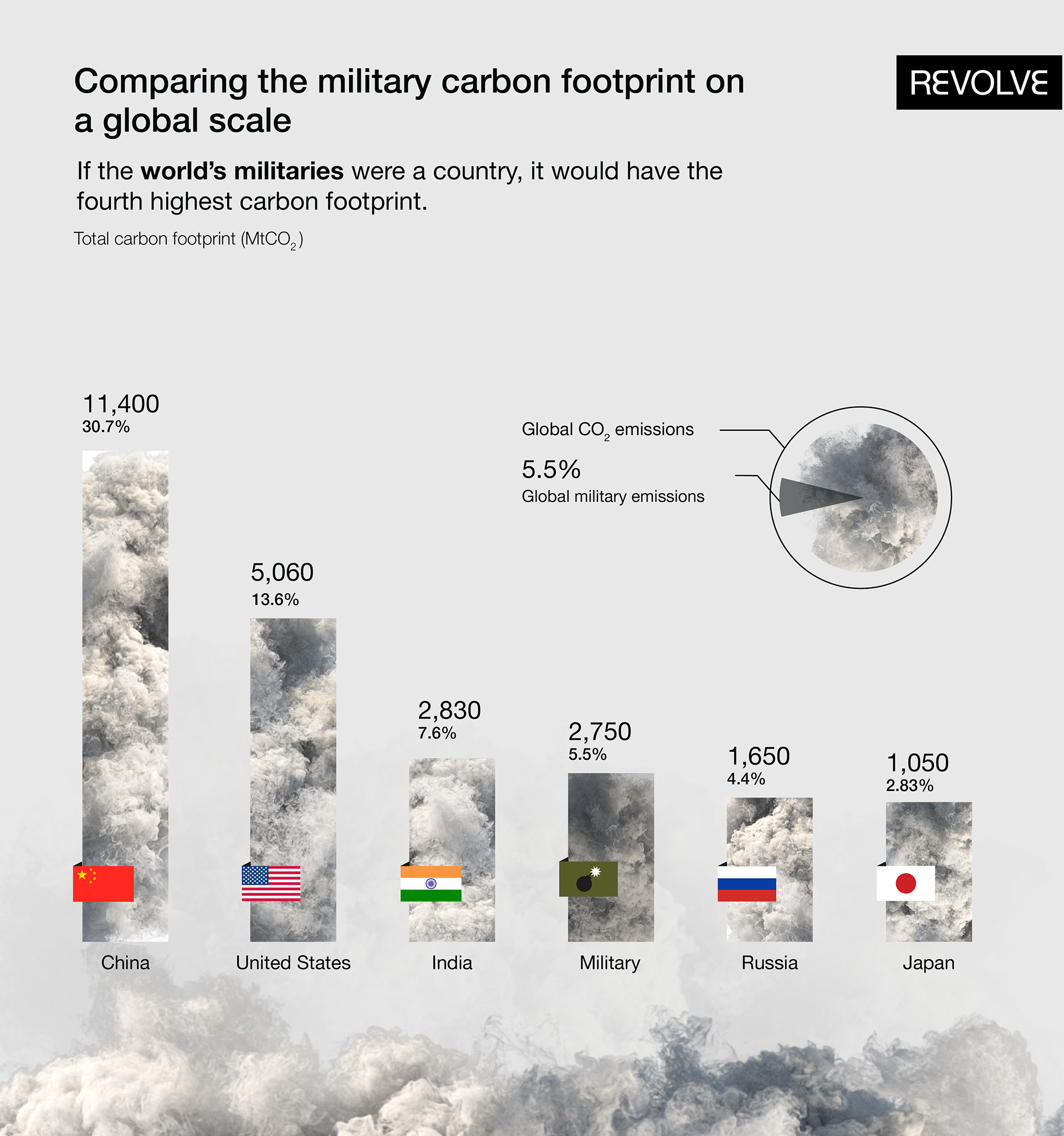

In 2022, the military’s global GHG emissions were estimated to surpass the national carbon footprint of Russia, which is a major petrostate. Specifically, the total carbon footprint was estimated to be around 5.5% of global emissions. This exceeds the global aviation and shipping emissions combined. With the provided data, if we assume that the global military was a country, it would be the fourth with the highest national carbon footprint!

The research excluded warfighting emissions, such as infrastructural damage, ecosystem degradation, fire, healthcare for survivors, and post-conflict reconstruction. Also, non-CO2 heating effects from contrail creation were excluded by the methodology used.

Research showed that the first 60 days of the Israel-Gaza war contributed to emissions exceeding the total annual emissions of 20 individual countries and territories.

In the ongoing devastating wars in Gaza and Ukraine, these climate impacts are expected to be even greater. For instance, research showed that the first 60 days of the Israel-Gaza war contributed to emissions exceeding the total annual emissions of 20 individual countries and territories.

On top of that, NATO targets to increase financing of the military, while failing to reduce emissions in any of their operations. In 2023, the military carbon footprint of NATO was 30 million more tons of CO2 than in 2021, which is equivalent to putting over 8 million extra cars on the road.

There is, however, some good news. Based on Neta Crawford, a professor of international relations at Oxford University, there is some progress in fuel reduction from the US Department of Defense (DOD). The scientist has mentioned that more fuel-efficient vehicles, the employment of renewable energy, fewer and smaller military exercises, as well as US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq, have contributed to fuel use decline.

The reduction of polluting fuels can also decrease climate change threats to national security, such as conflicts over basic resources like food and water. Yet, Crawford highlights that DOD is still a significant consumer of fossil fuel energy, being the largest institution in petroleum use and GHG production worldwide.

In 2022, the total global military expenditure surged by 3.7 percent – an increasing trend for the eighth consecutive year. For Europe, it was the steepest year-on-year increase in at least 30 years, due to the war in Ukraine. “The continuous rise in global military expenditure in recent years is a sign that we are living in an increasingly insecure world,” Dr Nan Tian, Senior Researcher with SIPRI’s Military Expenditure and Arms Production Program, said.

NATO has announced a new target to increase enormously the military budget in the forthcoming four years. Already, research shows that more than half of the global military costs were spent by NATO members, reaching globally a record high of €2.05 trillion in 2022. Despite the climate and social impacts of the military expansion, a minimum of 2% of the NATO state’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is expected to be used for the military, and the related target of at least 20% of expenditure on equipment.

In 2022, the total global military expenditure surged by 3.7 percent – an increasing trend for the eighth consecutive year.

It is estimated that if all 31 countries reach their 2% target by 2028, this would amount to an additional cost of €2.35 trillion. This enormous amount could cover the climate adaptation costs for low- and middle-income countries for seven years. Otherwise, zooming in on the European Union, it is estimated that the €1 trillion extra spending needed to achieve the 2% of GDP target for military expenditure of the European NATO members equals the total financing for the European Green Deal. NATO has therefore starkly ignored the IPCC recommendation of a 43% decline in GHG emissions by 2030 to keep global average temperature increases below 1.5°C.

A promising step on hold

If we consider that current methodologies for calculating military emissions have their imperfections, lacking data makes relevant assumptions even less accurate. Hence, it is crucial that transparent reporting is happening. Precise data can help scientists to make more accurate calculations about the global GHG emissions and member states can record their progress for national net zero targets.

We urgently need to escape the vicious cycle between wars and climate change, as one feeds the other. Research from the Nature Journal showed that intensifying climate change is estimated to increase future risks of conflict and increased military activity leads to greater emissions and uncertainty at many levels. And like the environmental policy officer Linsey Cottrell said, “a failure to act on military emissions poses a far greater risk to our security than reporting them will ever do.”

A promising step was the resolution that the European Parliament passed ahead of COP28, which called for a transparent accounting of military emissions to the UNFCCC. One of the amendments was proposed by Swedish MEP Pär Holmgren (Greens/European Free Alliance) and it calls for “the Member States to ensure that military GHG emissions are included in domestic net-zero targets to accelerate the development of decarbonization technologies and strategies.”

The €1 trillion extra spending needed to achieve the 2% of GDP target for military expenditure of the European NATO members equals the total financing for the European Green Deal.

The other amendment, proposed by MEPs from the Left stressed that “all sectors must contribute to the reduction of emissions, including the defense sector while maintaining operational effectiveness, and that the development of decarbonization technologies and strategies in the defense sector should be accelerated.” Both amendments were faced with backlashes from the far-right Identity and Democracy Group.

In 2023, researchers and civil society organizations made a joint submission to the UNFCCC where they wrote: “Our climate emergency can no longer afford to permit the ‘business as usual’ omission of military and conflict-related emissions within the UNFCCC process.”

Despite these efforts, real action is yet to be taken. The forthcoming EU elections in June might be an opportunity to take responsibility, as it is crucial to impose military emission accounting to improve the European Green Deal and reduce potential conflicts and climate risks.

In the end, it is about applying the European Climate Law that mentions “Improving climate resilience and adaptive capacities to climate change requires shared efforts by all sectors of the economy and society.”