Soil: A Dirty Word?

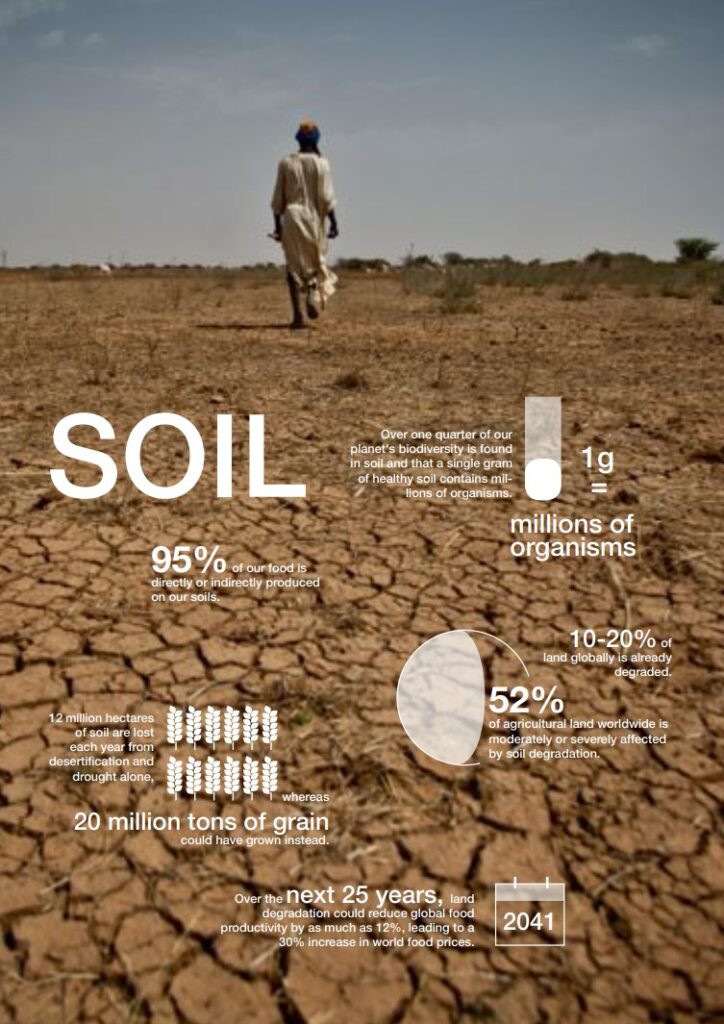

Soil is vital for the survival of all life on earth. Ninety-five per cent of our food is directly or indirectly produced on our soils and without healthy soils, humans, plants and animals will slowly die out.

Soil or dirt. Whether you prefer the British or the American word, the connotation is the same. We talk of something being “soiled”, of using “dirty money” or “digging up the dirt”. None of these expressions conjure up positive images, indeed they do quite the reverse. Yet soil, or dirt, is the foundation of life. “For all things come from earth, and all things end by becoming earth,” as Greek philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon is quoted as having said. However, worldwide soil is being at best neglected, at worst destroyed. We are familiar with images of desertification in Africa, but the situation is not that much better in many European countries. One of the main reasons for this neglect is that while the European Union has legislation to protect water and air, soil, despite concerted efforts from environmental NGOs, is left to defend itself, as the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) explains.

Soil is vital for the survival of all life on earth. Ninety-five per cent of our food is directly or indirectly produced on our soils and without healthy soils, humans, plants and animals will slowly die out. Indeed, soils host over one quarter of all biodiversity on Earth and just one single gram of healthy soil contains millions of organisms. However, 10-20% of land globally is already in bad shape, with over half of agricultural land worldwide moderately or severely affected by soil degradation, meaning that less food is likely to be produced on it than would otherwise be the case.

We are familiar with images of desertification in Africa, but the situation is not that much better in many European countries.

Lack of Action

Aware of such facts, in 2002, the European Commission decided it was time for action, publishing a communication entitled “Towards a Thematic Strategy for Soil Protection”. This paper was then followed by a broad two year consultation on the issue aimed at providing the EU executive with the views and information needed to create an EU soil protection policy. For a number of years, “difficult and sensitive” political discussions took place, according to a Commission paper. However, political agreement on the issue was never found as member states took increasingly entrenched political positions. In 2014, after eight years of political stalemate, the Commission decided to withdraw its proposal in favour of an “alternative initiative,” which is still to see the light of day.

Meanwhile, as policymakers spent years spouting plenty of hot air about the need to protect Europe’s soil, the situation underfoot was getting rapidly worse. This was underlined by the European Environment Agency’s State of the Environment report in 2015. This highlights continuing soil degradation across Europe and suggests that without action the situation will get worse. Land take, which most frequently means the urbanisation of farmland and forests, is the worst culprit and has many damaging effects on fertile agricultural soils, while also threatening biodiversity and increasing the risk of floods and water scarcity. As farmlands and woodlands are concreted over, the important services provided by soils such as the storing, filtering, and transforming of substances like nutrients, contaminants, and water delivery are impaired. And land take is a long-term change, which is difficult or costly to reverse; even if a decision is taken to dig up some of the concrete slabs, the damage has been done.

This lack of action is all the more frustrating given that EU policymakers from the Commission, Parliament and Council agreed via the 7th Environmental Action Plan, which entered into force on 1 January 2014, to tackle soil degradation. The 7EAP sets ambitious goals on soil and states that “The Union and Member States should also reflect as soon as possible on how soil quality issues could be addressed using a targeted and proportionate risk-based approach within a binding legal framework”.

The EU had the perfect opportunity to start turning these fine words into concrete proposals in 2015, which was deemed by the United Nations as the International Year of Soils. Yet, nothing happened. It seems that for now at least member state vested interests are continuing to win out over the scientifically proven need to protect Europe’s soils. It is as if soil has become a dirty word in the EU. This is a strange situation to be in when the facts speak for themselves.

As highlighted by the 7EAP, more than 25% of the EU’s land is affected by soil erosion by water, causing the types of problems mentioned earlier in this article. Indeed, according to recent research, Britain has only 100 harvests left in its farm soil, while the soil in more than half a million sites across the EU are thought to be contaminated and until they are identified and assessed they will “continue to pose potentially serious environmental, economic, social and health risks,” states the 7EAP. “Every year more than 1000 km2 of land are taken for housing, industry, transport or recreational purposes” in Europe, it adds.

As farmlands and woodlands are concreted over, the important services provided by soils and water delivery are impaired.

The recent floods in the UK are proof enough, if it were needed, of the real-life dangers of leaving soil to the mercies of urbanization, intensive farming and deforestation. Guardian columnist George Monbiot, for example, has written about how “rain that percolates into the soil is released more slowly than rain that flashes over the surface” thus reducing the risk of flooding. He insists that the proposed European Soil Framework Directive, which as we previously stated was withdrawn in 2014, would have “reduced flooding by preventing the erosion and compaction of the soil”.

Even the links between climate change and soil seem to be being ignored by policymakers looking to grab the headlines with big announcements about energy and infrastructure. Soil may be dirty, but it can play a big role in helping to clean up our carbon emissions and can therefore potentially play an important role in climate change mitigation by storing carbon and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere. Indeed, there is more carbon stored in soil than in the atmosphere and in vegetation combined. A release of just 0.1% of the carbon contained in European soils would be equal to the annual emissions of 100 million cars. And in the context of climate change adaptation, soils bare also a massive help, as indicated above with the example of flooding.

A Global Concern

Soil-related problems are a global issue. Erosion carries away 25 to 40 billion tonnes of topsoil every year, thereby significantly reducing crop yields. Indeed, annual cereal production losses due to erosion have been estimated at 7.6 million tonnes each year. If action is not taken to reduce erosion, a total reduction of over 253 million tonnes of cereals could be projected by 2050. This yield loss would be equivalent to removing 1.5 million square kilometres of land from crop production – or roughly all the arable land in India. Furthermore, lack of soil nutrients is the greatest obstacle to improving food production and soil function in many degraded landscapes. In Africa, all but three countries extract more nutrients from the soil each year than are returned through use of fertilisers, crop residues, manure, and other organic matter. Indeed, those closest to the soil, namely farmers, are unfortunately often complicit in its destruction. In Europe, subsidies from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) – to the tune of 50 million euros per year – have pushed farmers to embrace pollution-heavy production methods based around fertilisers and heavy machinery that, respectively, contaminate and compact the soil.

There is a slight glimmer of hope in this gloomy picture. Last September, all countries of the world signed up to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which included a commitment by 2030 to “ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices” that among other things “progressively improve land and soil quality”. Likewise, the goals call on signatories to, by the same date, “substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from” various threats including “soil pollution” and to “combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil…and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world”.

Committing to actions to achieve these goals would result in huge benefits for people, the environment and the economy. A report by the Economics of Land Degradation forecasts that over the next 25 years, land degradation could reduce global food productivity by as much as 12%, leading to a 30% increase in world food prices. This would likely result in greater hunger and violence as happened when world food prices increased dramatically in 2007-2008 sparking riots around the world. The EEB in conjunction with its partners in the People4Soil NGO coalition will, therefore, continue to push for EU legislation to protect soils and for Europe to lead international efforts to protect soil. As UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon said on World Soil Day last December: “Together, we can promote the cause of soils, a truly solid ground for life”.

The recent floods in the UK are proof enough of the real-life dangers of leaving soil to the mercies of urbanization, intensive farming and deforestation.

Rural migration due to degradation can exacerbate urban sprawl, and can bring about internal and cross-boundary social, ethnic, and political conflicts. Land issues have played a major role in at least 27 major conflicts in Africa since 1990.

Agriculture, forestry and other land uses are estimated to be responsible for about one quarter of anthropogenic GHG emissions. There is significant potential to reduce these emissions, largely through reduced CO2 emissions from agriculture, avoiding deforestation and forest degradation, creating net carbon sequestration in soils, and the provision of renewable energy through sustainable land management.

The annual economic losses due to deforestation and land degradation were estimated at € 1.5–3.4 trillion in 2008, equalling 3.3–7.5% of global GDP in 2008. This includes a startling loss of grain worth $1.2 billion annually.

On a global scale, an estimated annual loss of 75 billion tons of soil from arable land as consequence of degradation is assumed to cost the world about $400 billion per year, with the USA alone expected to lose $44 billion annually from soil erosion.

Land degradation is a top driver of deforestation: 13 million hectares of the world’s forests continue to be lost each year.

The European Environmental Bureau (EEB) is the largest federation of environmental citizens’ organizations in Europe. It currently consists of over 150 member organizations in more than 30 countries, including a growing number of European networks, and representing some 15 million individual members and supporters. They stand for environmental justice, sustainable development and participatory democracy. Their aim is to ensure the EU secures a healthy environment and rich biodiversity for all.