Revealing Non-wood Forest Products

The European Forest Institute (EFI) Mediterranean Facility explores and sheds light on the wealth of products that can boost the forest economy beyond wood.

When we think about the value of forests, we normally think about biodiversity, landscape, clear water and fresh air. When it comes to forest management and products, we think mainly about wood. It is easy to overlook the enormous potential of non-wood forest products (NWFPs) and how they can help us face societal challenges.

This is true even in the Mediterranean region, where wood production is limited and wood-based industries are not well developed. Research results from EU-funded projects like StarTree and INCREDIBLE4 are contributing to unveiling the enormous potential of NWFPs. These vital components of better preserved, better managed and better valued Mediterranean forests support more vibrant rural economies and healthier urban citizens. Surprised? We will go into the forest now to unearth some of its treasures.

Value of non-wood forest products

Non-wood products include wild and partially wild pine nuts, acorns and berries, as well as other edibles, such as mushrooms, honey, essential or medicinal herbs and fantastic natural and versatile materials, including cork and resin. Despite poor statistics and grey markets, the marketed value of non-wood forest products in Europe was estimated to be worth an enormous 2.3 billion euros. Even in wood-centred forest economies of northern or central Europe, non-wood forest products account for some 10% of the total value of round wood. Because of relatively weaker wood value chains and their very high biodiversity, these NWFPs represent a larger share of forest production in the Mediterranean region.

The opportunities offered by non-wood forest products go well beyond niche markets, small-scale activities and heritage. In fact, some rather traditional NWFPs can be found in global markets, in multiple innovative applications. For instance, in the case of cork, which is only produced in the Mediterranean basin in high biodiversity forests, around 40 million bottle stoppers are produced daily and exported to wine producing countries around the world. But cork has a use that goes way beyond keeping wine in a bottle. Due to its excellent mechanical, thermal and acoustic properties, an impressive portfolio of innovative products have been developed, from fashion to construction and aeronautics. High-quality flooring, digitally printed wall panels, thermal protection for SpaceX Falcon rockets re-entry modules and, of course, fashion garments.

Portugal has led this cork revolution through a strong focus on innovation and sustainable forest management. Cork is now one of its main export sectors and an inspiration to other Mediterranean cork producing regions.

New uses for ancient products

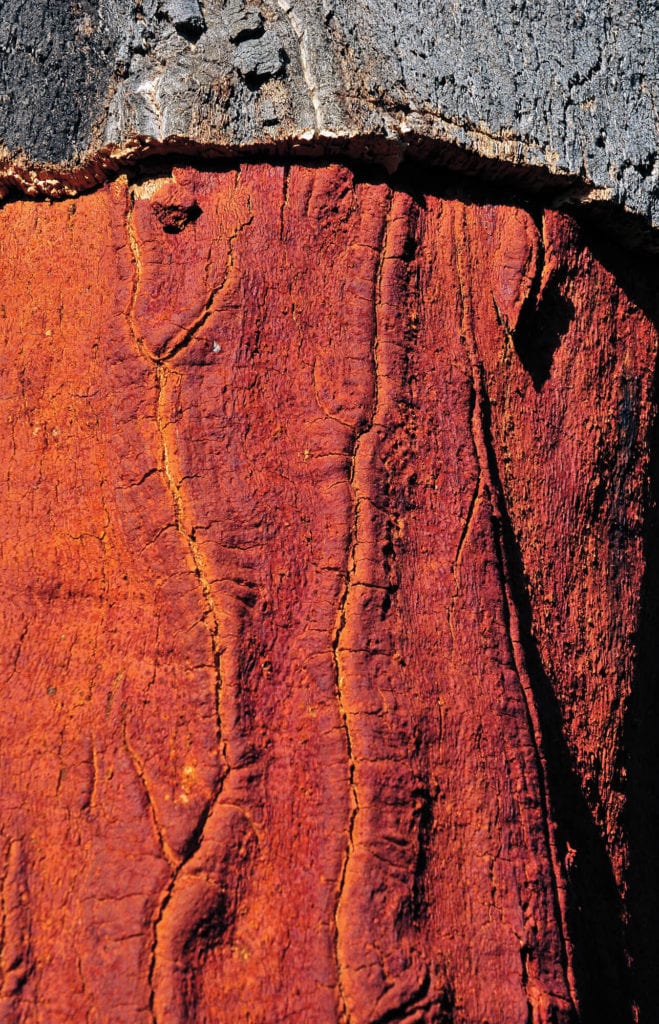

The need to transition towards a fossil fuel free economy and changing market conditions are re-opening opportunities for old, almost abandoned products, like resin. In central Spain, resin production was restored in over 20,000 hectares (ha) of abandoned pine forests, attracting investments in new processing facilities. Natural resin derivates are a must in the high-quality cosmetics industry and can replace oil derivatives in multiple green chemistry applications. With over 800,000 ha of favourable pine forests, resin production represents a significant opportunity for the post-oil era in the Mediterranean, even if the cost of labour is a major limitation in current market conditions.

Similarly, interest for natural tannins is coming back in Italy. Genuine Italian Vegetable Tanned Leather is a quality brand for the fashion industry, key for Italian leather competitiveness in global markets, showing how the importance of NWFPs go beyond their monetary value.

Indeed, the wealth of NWFPs is immense, with essential oils, medicinal herb-based products and specialty extracts from leaves, seeds and bark collected and cultivated around the Mediterranean increasingly used as raw materials for health, nutraceutical and cosmetic industries.

A walk on the wild side

Dedicated forest management (with a range of management intensities) is essential for ensuring production of certain NWFPs, for example cork, resin, as well as chestnut and pine nuts in certain regions. Yet there are also many relevant wild forest products, which are collected but not actively managed. This is the case for many mushrooms and berries as well as for some honeys and medicinal or decorative plants.

Over 70% of people who pick products go to the forest more than three times a year.

The lack of data and statistics should not mislead us when judging the relevance of these wild forest products. A household survey conducted in 2015 by the StarTree project, asked 17,000 European citizens about their wild NWFP consumption habits – the results are astonishing: it turns out that over 90% of Europeans consumed some type of wild forest product every year; more importantly, 35% of rural and 22% of urban respondents picked or harvested products themselves during the year, although with big regional differences, and with relatively more people picking the products themselves in Nordic and central Europe and fewer in southern and Atlantic countries. Over 70% of people who pick products go to the forest more than three times a year.

Non-wood forest products and urban lifestyles

Like many areas around the world, Mediterranean Europe is facing increasing urbanization, with almost three quarters of the population living in cities, towns and suburbs. Citizens live in increasing isolation from nature and outdoor experiences and this is already becoming a public health problem. The concept of Nature deficit disorderdescribes the human costs of alienation from the natural world and this has a specific impact on children.

Meanwhile, the lack of opportunities in rural areas leads to rural abandonment and human desertification, or else over-exploited, fragile agro-ecosystems. In this context, the attraction potential of NWFPs and their capacity to bring citizens to nature must be leveraged to improve well-being in urban areas and a more balanced rural-urban relationship.

Some NWFPs benefits

There is considerable potential for wild, non-wood forest products to encourage nature-based tourism and generate income in rural areas. The experiential tourism mega-trend is behind innovations using NWFPs as iconic products in territorial marketing initiatives for branding a geographic area and networking its actors, such as the Strada del porcino, the Route de la châtaigne, and others. Mycological tourism, showing traceability of wild food from the forest to the restaurant or mushroom-picking courses are gaining in popularity and making it onto mainstream TV. In experiential tourism, visitors’ experiences are essential to the value.

Nature deficit disorder is the cost on human mental and physical health of being alienated from the natural world; this disconnection serious impacts on all ages, especially children.

Linked to this is a second growing mega-trend towards a greater appreciation and use of locally-sourced, natural, traditional and wild resources. Wild and traditional products are increasingly present in the menus of quality restaurants, regional gastronomic offers, thermalism and spas. Linking NWFPs with tourism, short value chains and direct sales are good opportunities for diversifying income sources and providing employment in rural areas. In addition, the positive effects on human health of forest outdoor activities, such as mushroom and berry picking, can improve public health and represent significant savings to the medical bill. The question now is if we be able to translate those saving into investments to develop the necessary infrastructure and marketing strategies to boost social innovation in NWPF-rich rural areas.

What needs to be done

Developing NWFP-based economies presents structural limitations that need to be overcome. One critical limitation is seasonal and yearly variations in availability and quality of certain non-wood forest products. No rain, no mushrooms: it is as simple and as complex as that. A lack of a continuous, reliable flow of fresh products jeopardizes any effort to achieve a stable critical mass of products for the market.

The problem is exacerbated by the frequent atomization of supply and a typical lack of collaboration among actors along the different value chains. Typically, individual collectors sell a product to middlemen in largely, grey, informal markets. This limits traceability and respect for minimum standards for product storage and health. Non-registered transactions lead to tax evasion and, more importantly, can facilitate unfair labour conditions and conflicts between professional and leisure pickers. To improve supply chain arrangements, it is therefore essential to regulate harvesting rights and modalities, allowing that products can be traced (extremely important for edibles), avoiding unfair employment conditions, and balancing the rights of the local population and hobbyist with the needs of more professionalized operators.

Action must be taken to facilitate better cooperation among collectors and between collectors and processors. Modern digital technologies can help, with Internet-based portals and social networks becoming relevant commercialization channels and a great opportunity for NWFPs. One example is a high-quality brand for wild mushrooms developed in the Spanish region of Castilla y Leon, that integrates interested agro-food operators, guaranteeing consumers geographic origin, sustainable picking, safety, and high visual and culinary quality, while also establishing economies-of-scale and joint marketing efforts. The brand builds upon a comprehensive effort that includes awareness and marketing campaigns, new picking regulations and a network of ICT-enabled mobile selling points where people who have picked the products can sell their daily harvest with full web-based traceability and transparency.

In the case of already well-established, industrial products (like cork and resin) that compete in global markets with cheap (frequently non-renewable) oil derivatives, the ability to supply raw material in quantity and quality is a limiting factor. Could it be that high labour costs and tight completion in the markets is the reason why limited cork or resin is produced in high-income countries like France or Italy?

It is, of course, a multifaceted problem that might require new approaches to achieve profitability, for example by combining NWFP production with wood and other goods or services, supported with Payments for Ecosystem Service type schemes such as in dehesas or montados. Is also about investing in research and development, promoting entrepreneurial attitudes and improved access to finance for forest bioeconomy start-ups.

Could non-wood forest products safeguard our future?

In the northern Mediterranean, forests are expanding as rapidly as villages are emptying and traditional agricultural activities are abandoned. There is little incentive and capacity to manage forests and, thus, to adapt actively to climate change and to better prevent the increasing risk of mega-fires. In southern and eastern Mediterranean countries, where rural areas are more densely populated, the lack of sustainable revenues from the forest leads to increased deforestation pressures that can be overcome by strong governmental policies. In both cases, society seems to have lost the capacity to generate sustainable value from forests. Being able to create more worth from forests by leveraging the potential of non-wood forest products in comprehensive, transdisciplinary strategies could provide the necessary economic engine to implement sustainable forest management and to help our forests, and our society, navigate the stormy waters of global change.