Plastic Pollution

Understanding the full consequences of more than 70 years of global plastic obsession.

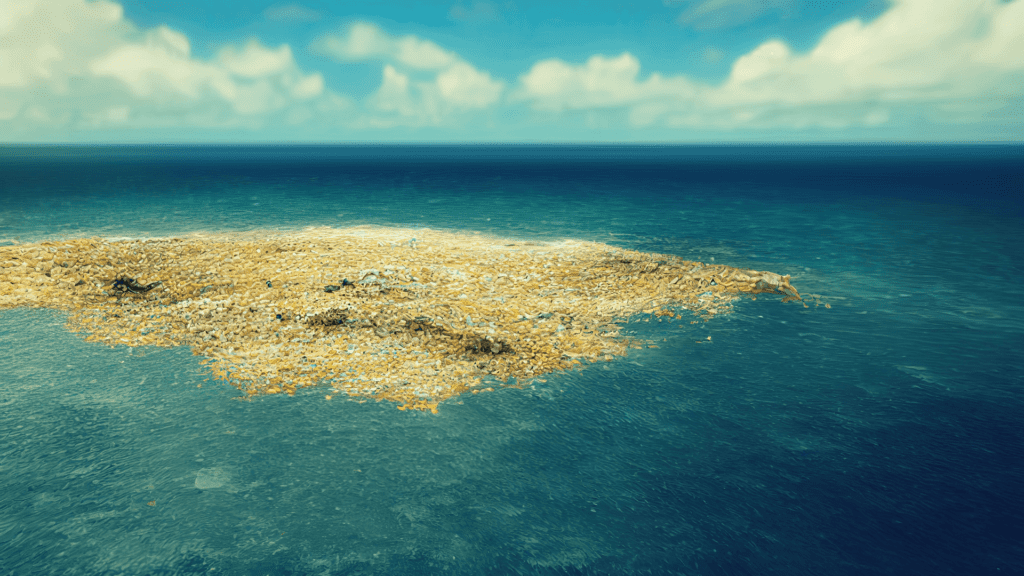

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch might be the most striking and visible representation of marine debris. The socalled Plastic Continent is a collection of marine litter floating in the gyre of the North Pacific Ocean. However, the garbage continent is just a visible impact, what is harder to see are the widespread impacts on human health, ecosystems, and wildlife.

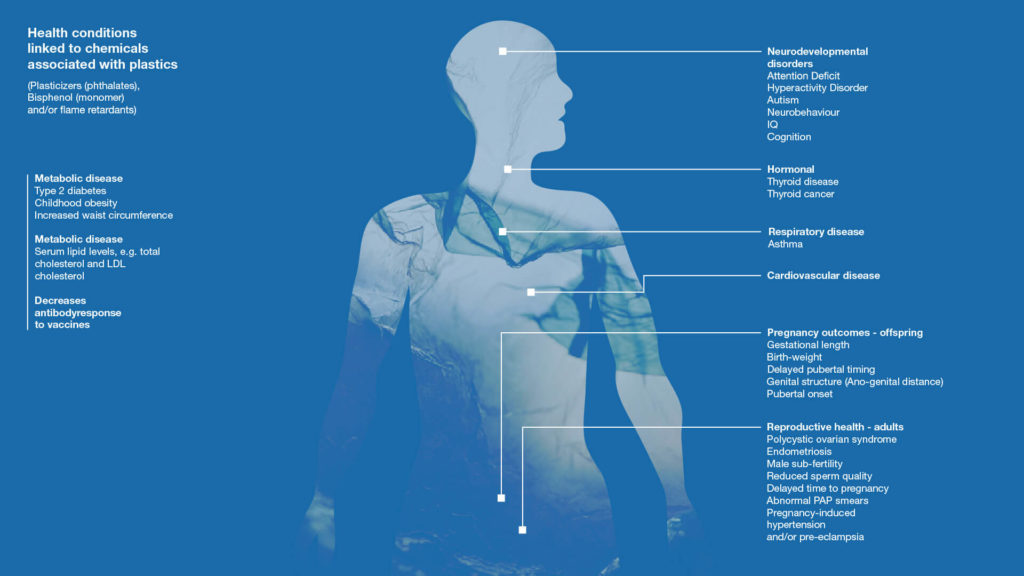

The connection between plastic chemicals in the marine environment and human health has not yet been studied in depth. However, some of the chemicals present in plastics “are associated with serious health impacts, especially in women,” as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) highlighted in its global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution.

“Not all the chemicals in plastics are hazardous but one quarter is of concern,” claims Magali Outters, the team leader of the Policy Area at MedWaves – the UNEP/MAP Regional Activity Centre for Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) – who emphasized that the main problem is the lack of transparency and regulation in the composition of plastics.

Plastic everywhere

Over the last 70 years, plastics have penetrated every aspect of our life. This versatile material started its significant expansion during and right after the Second World War. Plastic does not need to be constantly demonized. It can provide important benefits, from life-saving medical devices to safe and long-life food storage. However, unnecessary and avoidable plastics, particularly single-use packaging and disposable items, are polluting our planet at alarming rates, as the UNEP report highlighted.

The From Pollution to Solution report showcases that decades of economic growth and an increasing dependency on throw-away plastics have taken us to the current torrent of unmanaged waste that “pours into lakes, rivers, coastal environments, and finally out to sea, triggering a ripple of problems.” According to UNEP predictions, the estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic entering the ocean annually will triple in the next twenty years reaching 37 million metric tons. That is equivalent to 50kg of plastics per meter of coastline worldwide.

According to UNEP predictions, the estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic entering the ocean annually will triple in the next 20 years reaching 37 million metric tons.

On a global scale, plastic pollution has become an epidemic and needs to be stopped. It might seem surprising but the first reports of the negative impact of marine plastic debris on marine species date back to the 1960s. However, it was not until 2022 that the UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi endorsed a historic resolution “to end plastic pollution, and forge an international legally binding agreement, by the end of 2024.” This means that Heads of State, environment ministers, and other representatives from 175 nations acknowledged the urgency of this problem and the need to take action.

Forever chemicals in plastics… in the sea… and in humans

Plastic waste can be found across the planet, from the Arctic to Everest to the Mariana trench, and traces of plastic chemical components can be found in the blood of European and American citizens, affirmed the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). The poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – also known as ‘forever chemicals’ for their high persistence – are present in many plastics used for food packaging such as microwave popcorn bags or fast food wrappings.

There are 4,700 substances listed as PFAS in the OECD’s Global Database, so why are we being poisoned with these chemicals if they are identified? One of the answers is the opacity in the composition of the plastics. “Now we know the polymers in the plastic, but not the chemicals,” Outters explains.

Plastic is a highly resistant material due to the combination of chemicals that compose it. More than half of the plastics found floating in some gyres were produced in the 1990s and earlier, showed the report ‘From Pollution to Solution’. The plastic composition has been refined over decades to develop a vast range of versatile products that can be present in every sphere of life. PFAS play an important role in plastic persistence. “Even if we stopped manufacturing PFAS tomorrow, they would still be around for generations as no other manufactured chemicals stay in the environment as long as them,” stressed the ECHA.

Chemicals are very minute but they pose a serious threat. Some of the chemicals associated with plastics are recognized as mutagens and carcinogens, as scientific evidence has shown. “Exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) can lead to serious health effects including certain cancers, birth defects, dysfunctional immune and reproductive systems, greater susceptibility to disease and damages to the central and peripheral nervous systems,” pointed out the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

Looking into more detail marine plastics, the UNEP report pointed out a gap saying that “the potential health hazards of the polymers that are the structural backbone of marine plastics have been less well studied.” The main concerns are the infamous microplastic and nanoplastic particles and microfibres formed when plastic waste enters the oceans and breaks down under the influence of weathering, mechanical abrasion, and photodegradation.

The annual intake of microplastics by some humans has been estimated to range from 39,000 to 52,000 particles, depending on age and gender, rising to 74,000 to 121,000 particles when inhalation is considered, according to research published in the Environmental Science and Technology Journal. The exposure from marine sources is most likely to be via ingestion of seafood rather than inhalation. The overall exposure levels and health impacts remain uncertain as well as the gender-disaggregated data on those impacts. However, the evidence available shows that women have tested for significantly higher levels of toxic chemicals, as the report Plastics, Gender and the Environment highlights.

Is there a way forward?

The Stockholm Convention emerged as a global answer to the threat of ‘forever chemicals’. The Convention was adopted in 2001 and entered into force in 2004. It is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from chemicals that remain intact in the environment for long periods, become widely distributed geographically, accumulate in the fatty tissue of humans and wildlife, and have harmful impacts on human health or on the environment.

The Convention is almost universal regarding geographical coverage and 186 countries. The long-range transport of chemicals makes no government able to act alone in protecting its citizens or its environment from the forever chemicals.

Banning chemicals is difficult, as Magali Outters highlights: “We need different approaches to ban groups of chemicals.” Magali leads the policy area of MedWaves, part of the worldwide network of sixteen regional center of Stockholm Convention to provide technical assistance and to promote the transfer of technology. This responsibility brings a special mandate to assist Mediterranean countries in phasing out toxic chemicals and transitioning to safe and innovative alternatives.

MedWaves – a member of the AMWAJ Alliance – links key topics to ensure more sustainable consumption and production: circular economy, sustainable blue economy, marine litter and plastics, and toxic chemicals. The center works to build bridges between the global and regional level efforts and different actors at the regional and local levels, such as experts, civil society and policy-makers.

The Mediterranean region is one of the world’s most affected areas regarding plastic marine litter. Plastics account for 95-100% of total floating litter and over 50% of seabed litter, as was highlighted in the data shared by the Mediterranean Action Plan of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/MAP). The Mediterranean region is also the world’s fourth-largest producer of plastic goods, underlined in the ‘From Pollution to Solution’ report.

Tourism plays an important role in plastic waste generation increasing it by up to 1/3 during the summer in some Mediterranean countries. Poor waste management is also a key element in reducing the impact of the litter produced on land on the water ecosystem and human health. For that, “there is not a single solution but different approaches such as regulation, agreements such as Plastic Pacts, public-private collaboration, or labeling,” as Magali asserts.

Any of these solutions like regulations or banning have a socio-economic impact that needs to be measured. It is important to also look at the situation at a national and local level. For example, regarding waste management. As Magali explained in her conversation with REVOLVE, the waste management sector is sometimes an informal sector in some countries of the region. That is translated normally in workers coming from a low-income part of society that work unsafely managing toxic products – like burning waste that contains plastic; Magali says: “We need to integrate them in the sector.”

Switching sides: cooperation and exchange of solutions

Phasing out plastics and tackling plastic pollution is taking more attention lately. As Inger Andersen – Executive Director of UNEP – underlines in the foreword of the ‘From Pollution to Solution’ report, “it is vital that we use this momentum to focus on opportunities across the life cycle of plastics and from source-to-sea for clean, healthy and resilient oceans.” And there are plenty of approaches to seize that momentum.

Besides regulations, like the historic adoption of the Council of the EU in October 2022 to reduce the presence of persistent organic pollutants in waste, there are plenty of initiatives, organizations, and individuals working to shift away from plastics and toxic chemicals around the Mediterranean, such as The Switchers Community – an inspirational network of green entrepreneurs funded by MedWaves.

To phase out plastics, there has to be solutions proposed and the Switchers Community focuses on that. The members are green and circular businesses implementing eco-innovative solutions that contribute to sustainable and fair consumption and production models. Many of the Switchers are focused on toxic chemical-free products and the sound management of plastics, like Staramaki and Mumo. These Switchers, based in Greece and Turkey respectively, work on alternatives to single-use plastic products like food wrapping and straws.

This community is an example of two of the key elements to any change of paradigm: cooperation and available alternatives. Initiatives like the Switchers show that there are alternatives and solutions and that we can cooperate to make them happen. As Ms. Outters claims: “it is important to show solutions and actions implemented in the field.” That is the way forward to spark change and action.