Global Dynamics of Urban Water Security

We’re running out of water and time as cities are becoming increasingly water scarce, requiring a new approach to addressing urban water security.

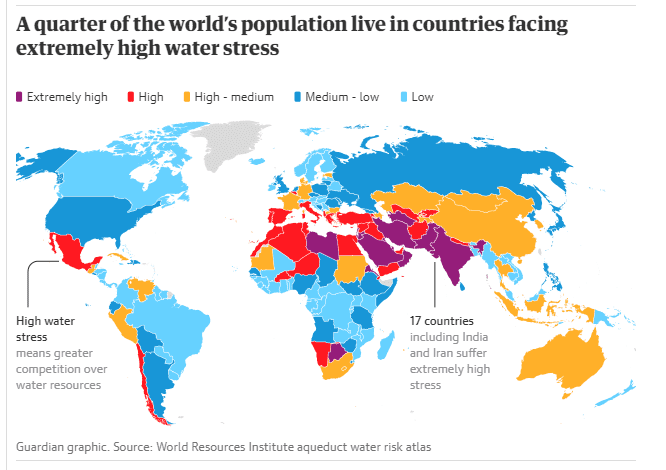

In what’s becoming an increasing trend, many cities around the world are at risk of running out of water, with water availability now cited as one of the greatest risks to business continuity and growth according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report. The latest cities that made international headlines of “day zeros” are Chennai (India), and Cape Town (South Africa). Severe water shortage is already affecting many cities and around 1.2 billion people globally – almost one-fifth of the world’s population – that live in areas of physical water scarcity, and another 500 million people are quickly approaching this situation living under water stress. Water demand has outstripped supplies in many areas such as the Arab region – the most water scarce region in the world – that is expected to head toward a disastrous water crisis if we continue with business as usual.

Why are cities running out of water, and who’s next?

It’s an urgent question for most cities around the world, in particular the Arab region which has been suffering from chronic water scarcity for years. Arab people receive water some hours per day or per week, often in less than 24 hours and therefore store water in roof tanks, in what is called intermittent water supply (IWS). IWS in common in most cities of the Arab countries such as Jordan and Lebanon. Many cities face great pressure to shift from 24/7 supply to IWS such as Egypt’s cities – the largest in the Arab world – which is already among top the 50 most water-stressed countries in the world, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI). Most Egyptians are currently receiving water 24/7 (continuous water supply) except some areas, mainly supplied by the only water source – the Nile River. With population growth, expansion in 20 new cities, climate change and uncertainties from upstream dams, many cities in the future may face great challenges – if we keep on business as usual – to meet the Sustainable Development Goal #6 on achieving water security for all.

Water in Egypt touches every aspect of development and plays a crucial role in achieving the 17 SDGs and “Egypt’s vision 2030”. Simply put: No Water, No Future.

Business as usual is no longer a guide to our future

A responsible path is particularly important in water development in many countries because, given the longevity of water infrastructure, many of these decisions will have long-term consequences. Furthermore, many decisions – both decisions to act and not to act – may have irreversible consequences.

At the core of many challenges of the urban water supply and sanitation sector is the vicious cycle of water management. Non-revenue water is high; water is often supplied only for a few hours a day or even a week; little effort has been made to involve water users and vulnerable people to provide them with the most appropriate types of affordable water and sanitation services; tariffs are so low; many cities cannot cover the operation and maintenance costs; and wastewater is in most cases not adequately treated, leading to environmental and health hazards.

As a former Director of the World Bank involved in water and infrastructure related issues for over two decades, I have a first-hand experience of water-security issues, what works, what should be done at what scale, and of course several bad experiences of poor management of this vital resource in many countries. Apart from being used as a political tool, water can also be a trigger for violent conflict.

Jamal Saghir

What does urban water security mean?

80% of GDP is produced in cities – so there are major economic repercussions. Urban areas have been experiencing major transitions and are facing formidable challenges of increasing demands due to population and economic growth, and the influx of displaced people coupled with the climate risks. All these pressures pose threats to socio-economic development and human and water security, such as inadequate water and sanitation services, failing stormwater management, and water quality and ecosystem degradation. There is a need for urgent action to ensure urban water security for all to prevent the coming water crisis and leapfrog to achieve the 2030 Agenda of Sustainable Development.

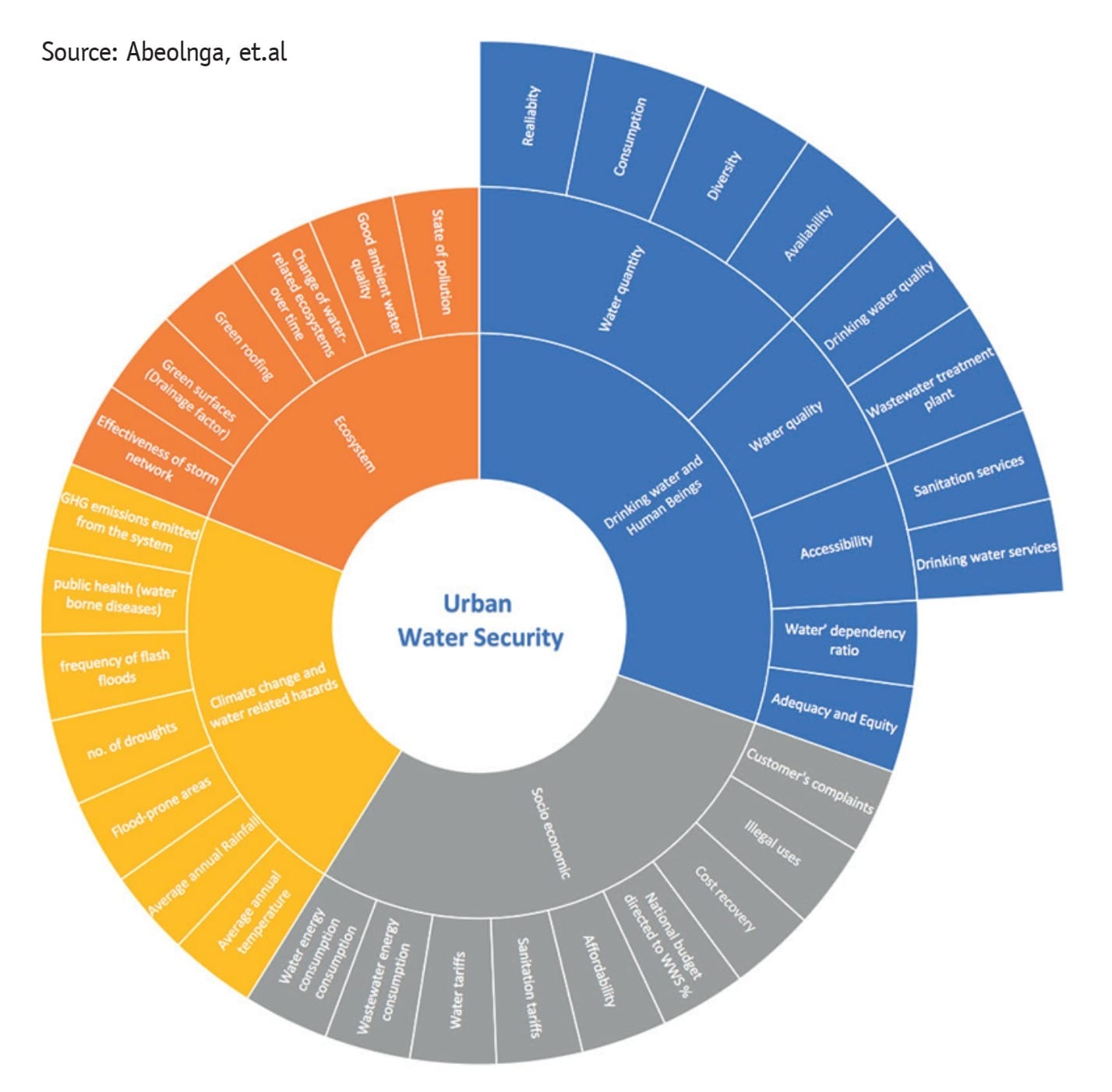

Although there are many definitions of water security, there is no clear or widely-endorsed definition of urban water security: some frameworks focus on risks, while others have adopted a broad understanding with a focus on the development of water resources to meet human needs. Our article proposes a new definition to integrate perspectives from the Sustainable Development Goal of Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG6) and the UN’s Human Right to Water and Sanitation in Resolution 64/292, which specifies different elements embedded in urban water security. We propose an urban water security definition which emphasizes the role of water stakeholders to define the elusive terminologies embedded in the definition, such as adequate and acceptable, as it will not be a one-size-fits-all proposition.

Urban water security should be defined as: “The dynamic capacity of the water system and water stakeholders to safeguard sustainable and equitable access to adequate quantities and acceptable quality of water that is continuously, physically, and legally available at an affordable cost for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability.”

Turning water scarce cities into water secure cities

Framing the challenge of water security goes beyond single-issue indicators such as water stress, water quality, or access to water sanitation and includes holistic thinking about a community’s demands and expectations. There is growing recognition of the role that state fragility and local conflict can play in aggravating water insecurity: infrastructure may be seriously deteriorated and institutions may be weakened to the point where service providers are unable to procure basic water services and or properly manage water-related hazards, resulting in riots, migration, and loss of life.

The framework depends on four main dimensions to achieve urban water security: 1) drinking water and human beings (D), 2) ecosystems (E), 3) climate change and water-related hazards (C), and 4) socio-economic factors (S) – also known as the DECS framework. DECS enables the analysis of relationships and trade-offs between urbanization and water security, as well as between sectoral indicators. Applying this framework will help governments, policy-makers, and water stakeholders to target scant resources more effectively and sustainably. Our research paper on water security reveals that achieving urban water security requires a holistic and integrated approach with collaborative stakeholders to provide a meaningful way to improve understanding and managing urban water security.

To achieve urban water security and sustainable water management, we need collective actions to implement the integrated DECS framework and more is needed to enhance the role of the private sector and civil society. Actions by governments and the international community are only part of the solution to solve the most serious water challenges. Under an effective policy and regulatory framework, the private sector could play a greater role in supplying cost effective and quality water service, as well as in harnessing and developing new technologies that enhance water security. Civil society, academia, and the media also have important contributions to make. Much greater public information is needed to educate people about the availability of water resources, the affiliated costs and the consequences of using water more sustainably.

Water Scarce City in Transition to Water Secure City (Madaba, Jordan)

Madaba lies in the middle of Jordan, 35km southwest of the capital Amman. It has an area of about 1,000km² and a population of 190,000 inhabitants. It is good example of a water scarce city in transition from water scarce city into water secure city. Madaba is rising above the challenge of urban water scarcity and climate change by building the resilience of the urban water system and investing in energy efficiency to ensure urban water security. The DECS framework will be applied in Madaba to provide holistic assessment with addressing the key priorities and determinants for sustainable urban water security.