People x Projects: Engaging Local Communities

When it comes to mobility planning, input from local residents is key to addressing community needs.

History has shown that involving citizens in the planning process is essential for sustainable urban mobility. Citizen involvement has sometimes resulted in projects being canceled or modified. For example, from the 1950s through the 1970s, citizens across cities in the United States opposed the construction of highways due to their negative effects on urban life in a movement known as ‘freeway revolts’. This opposition was fueled by grassroots movements and motivated by a disagreement with the top-down decision-making process used by the highway authorities which hardly involved any citizens. As a result of this opposition, highway construction was halted in several major cities. All these efforts ultimately led to the creation of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.

There are a few similar examples in India. However, compared to the United States, the corollary of non-involved citizens and the resulting discontent is still true. We have a number of similar projects, the most iconic of which is the Steel Flyover protests in Bangalore, which symbolized the discontent of non-involved citizens. The proposed 6.7 km long elevated corridor faced strong opposition from various groups who argued that the project would lead to the loss of trees, displacement of people, and destruction of heritage structures. Namma Bengaluru, a citizen-led movement, organized protests against the project and used social media to spread awareness. Their sustained advocacy led to the project being scrapped by the government in March 2017, which was seen as a victory for citizens and sustainable urban development in Bangalore.

Why Engage?

The Great Walk of Athens is an ambitious project which was designed to create a pedestrian pathway through ancient archeological sites of central Athens along a car-free route and eventually create “the most beautiful walk in Europe.” The Great Walk planned a pilot phase of banning traffic across a zone of central Athens, but the pilot had to be rolled back for multiple reasons, including significant public opposition. The project continues to face public opposition as the local residents do not identify with its objectives and find it both expensive and a cause of gentrification of the area.

Being part of the process creates a sense of agency and belonging throughout the life of the project.

Many such public responses to mobility-related projects have led to their failure. Evidence suggests that when mobility projects – especially those which are planned as large-scale interventions – are implemented quickly with little or no public input, citizens are dissatisfied with the results. Alternatively, including community voices in planning mobility solutions creates a feeling of ownership amongst citizens for the potential solutions. Being part of the process creates a sense of agency and belonging throughout the life of the project. In the absence of participation, citizens may not trust the process and the projects, which often leads to resistance and/or unsuccessful implementation. The failure and scrapping of the Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) corridor in Delhi was a prime example of this lack of involvement of people during the planning process. The BRT was accused of causing congestion and delays, leading to inadequate ridership and revenue. Moreover, poor planning, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of public participation in the decision-making process were also cited as reasons for the project’s failure.

The involvement of people in mobility planning also adds local expertise and knowledge to the projects. External experts and consultants may not always be aware of the local issues and community priorities. For example, the monorail in Mumbai has not been able to attract as many riders as expected because of poorly planned stations and routes which did not consider the needs of the communities along the line.

Involving stakeholders can also lead to more cost-effective solutions and projects. Many current approaches in policy planning which emphasize involving a larger number of stakeholders (through the use of technology, for example) are premised on the assumption that cost efficiencies can be achieved by receiving inputs from citizens. In July 2021, Kochi Metropolitan Transport Authority launched Open Kochi as an open mobility network for the integration of various urban transport modes with input from citizens as well as other stakeholders through a digital mobility platform.

There are several other initiatives that are being adopted to incorporate the needs of citizens in mobility planning, keeping in mind the many benefits of community engagement. Cities are undertaking ‘Walking and Cycling Assessments’ to understand the existing conditions and needs of pedestrians and cyclists to propose short-term and long-term solutions. Some cities are also trying to understand citizen needs for improving first and last-mile connectivity of metro services through feeder bus services.

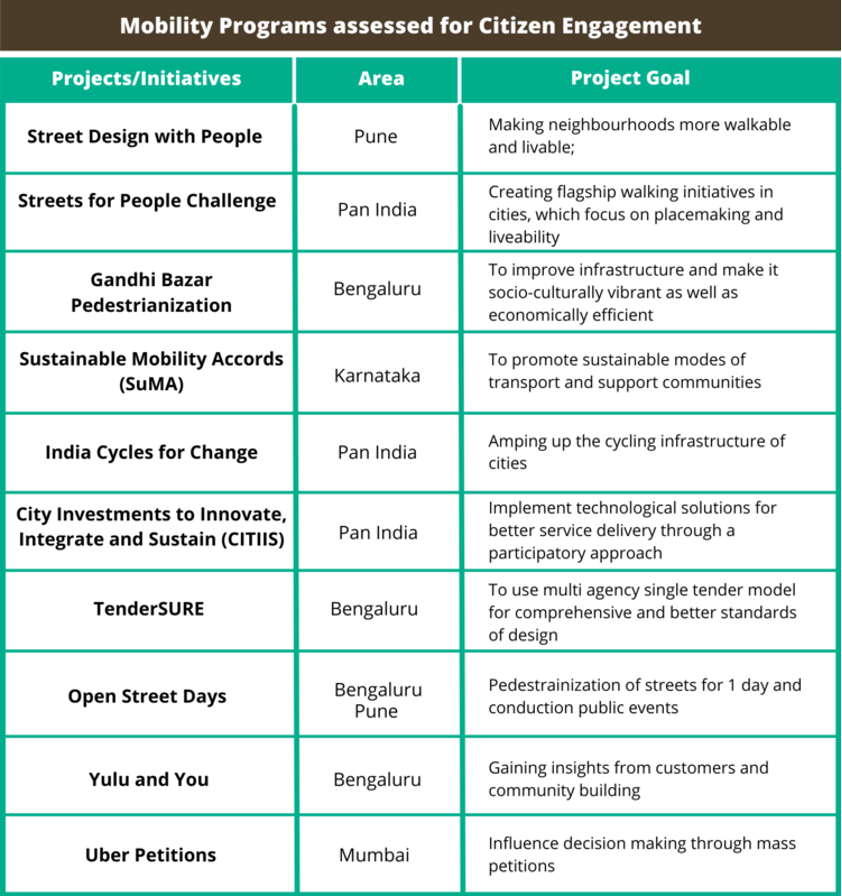

Another example is the City Investments to Innovate, Integrate and Sustain (CITIIS) program, which is jointly supported by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the European Union (EU). With a budget of 100 million euros, CITIIS is being coordinated and managed by the Program Management Unit (PMU) at the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) in New Delhi. CITIIS was launched in 2018 to provide financial and technical assistance to 12 selected cities in India for sustainable urban development. The selected projects will improve sustainable mobility, increase the amount of public open spaces, implement technology to improve e-governance, and drive social and organizational innovation in low-income settlements. The program combines financial assistance through loans and technical assistance through grants to the selected cities. This assistance focuses on strengthening institutions by committing resources to systematic planning (maturation phase) before implementation, developing results-based monitoring frameworks, and adopting technology for program monitoring. As an integral component of the Program Design, it includes a plan for engaging stakeholders in the design phase, which includes identifying and interacting with relevant stakeholders. CITIIS provides funding to different urban projects such as riverfront development, green mobility corridors, and ‘smart’ schools among others.

‘Invited’ and ‘Created’ Spaces for Citizen Engagement

Citizen engagement has gained traction and visibility in India, as communities and governments seek to address a range of complex challenges and opportunities. Several initiatives and platforms have emerged to facilitate this process, including digital tools and social media as well as the inclusion of civil society organizations in policy-making processes. However, effective citizen engagement and stakeholder participation still face challenges in India, including the need to build capacity and trust among diverse groups and to address power imbalances and other barriers to participation.

External experts and consultants may not always be aware of the local issues and community priorities.

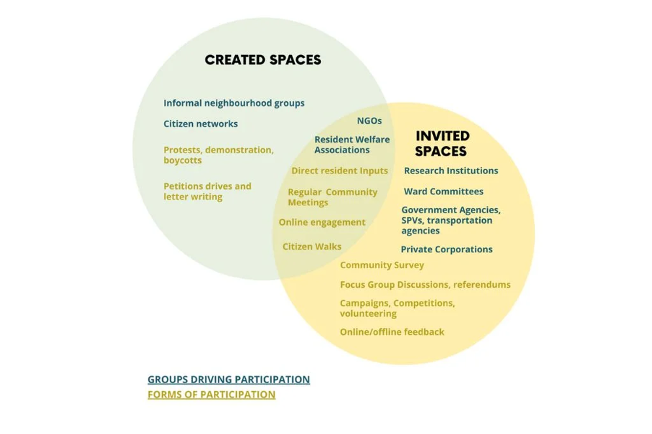

At Nagrika, we have been studying this engagement and have found that while there have been attempts, they are not institutionalized. We identified two types of spaces that engage citizens: ‘invited’ spaces, which are initiated by authorities or institutions; and ‘created’ spaces, which are self-organized by non-governmental organizations, community groups, and others to address self-defined issues. Very few cities in India have been using ward committees, a decentralized ‘invited space’ comprising of an elected representative from the ward along with citizens where ward-level plans and projects can be worked on collaboratively. However, more recently, there have been some urban programs that have formally invited spaces for citizen engagement. The CITIIS program and the Swachh Survekshan ranking system, which annually ranks Indian cities on parameters of cleanliness and sanitation are some such examples of invited spaces. In 2022, Swachh Survekshan collected feedback from over 11.4 million citizens in 4,355 cities on their awareness of the Swachhta app (official app to post feedback on civic-related issues); waste segregation, Swachh Survekshan survey, and waste recycling. An example of a created space is when citizens in Mysuru came together to protest a ropeway project that was leading to the felling of trees. It resulted in the ropeway project being canceled. The graphic below illustrates some of these spaces.

Even though such spaces exist for citizen engagement through the constitution, community-based organizations, or projects initiated by the city government, the representation of citizens in key decision-making for cities has remained limited. Community-based organizations have a long history of facilitating citizen participation in local decision-making, but they do not have decision-making power themselves. The Smart City Mission had focused on public participation in various mobility-related interventions through a variety of mediums, including online platforms and citizen committees, but has faced challenges in terms of citizen awareness and trust. Citizens are also generally not aware of existing and potential opportunities for participation and of the platforms where their voices can be heard.

Making a move, together

As India continues to urbanize at a rapid pace, involving citizens in the planning and decision-making process for urban mobility projects has become crucial. Though there are examples of mobility projects in India that demonstrate the negative consequences of not involving citizens, studies on the benefits of successful citizen engagement are limited in the Indian context. Despite an increase in citizen participation in mobility projects, a thorough analysis of the pros and cons of different engagement approaches is yet to be conducted, and the effectiveness of such measures is an area in need of further investigation. Furthermore, citizens are often not made aware of the potential ways they can benefit from providing input, and there is a lack of clear calls to action for their engagement.

As India continues to urbanize at a rapid pace, involving citizens in the planning and decision-making process for urban mobility projects has become crucial.

Many challenges remain in effectively engaging citizens in these projects. A deeper analysis of the various approaches and tools used for citizen engagement, as well as the role of technology, can enhance participation. Technology has played a significant role in shifting citizen engagement from passive feedback to active participation. For example, small and medium-sized cities in India, which make up most of the urban population, have been more active in using online spaces for civic engagement than larger metropolitan cities. Most often, citizen consultations are limited to the beginning of a project and not sustained throughout its life cycle. Similarly, only smaller-scale projects or limited aspects of larger projects witness any kind of engagement. The graphic below showcases some of the projects and initiatives which saw some form of citizen engagement.

Governments rarely seek feedback from citizens before (and definitely after) implementing a policy or program. To address this issue, governments could seek regular input from citizens throughout the project life-cycle, while citizen groups could hold implementing agencies accountable at later stages of the programs. This could become a two-way road. By allowing time for community members to become familiar with interventions and encouraging them to give input, they feel empowered to help shape their local environments, and valuable public money can be saved by creating sustainable mobility solutions that citizens will use.