India’s Struggle With Climate Adaptation

While mitigation is important, as climate patterns continue to change, adaptation needs equal attention.

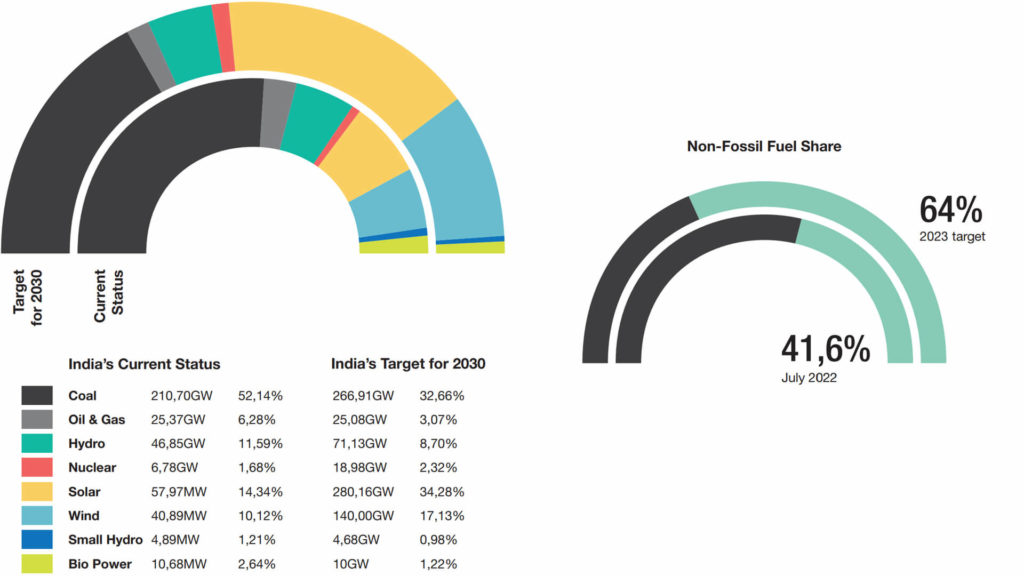

Several Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Reports (AR) have proven scientifically that countries like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are some of the most vulnerable countries to climate change in the world. India became the 3rd largest carbon emitter in the world in 2010. Yet, it aims to become a net zero emitter only by 2070, as declared by Prime Minister Modi at COP26 in 2021. The world’s largest democracy, however, is trying to get on the ‘green’ path: its leading International Solar Alliance and the introduction of its National Hydrogen Policy in 2022 most definitely show its commitment to fulfilling its ambitious plan to produce 50% of the nation’s total energy through renewable power by 2030. As the third largest energy-consuming country in the world, it has installed about 159.95 GW that already caters approximately 40% (including hydro) of the country’s total capacity.

A key finding of the IPCC AR6 report is that despite many international efforts to address the climate crises through mitigation since the 1990s, the period between 2010–2019 was the highest emitting decade on record. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reported that the Indian subcontinent is facing an increasing frequency of heatwaves in the last 30 years since 1986. The WMO predicts that the intensity, duration, and frequency of heatwaves are going to increase substantially in the upcoming years. India has faced an increase in uncertain environmental disasters such as cyclones, glacier melts, heat waves, floods, and others. The month of March 2022 was the hottest it has ever been in the last 122 years. Temperatures continued to rise and went up to 49 degrees Celsius in several states of India at the end of April. If nothing else, such climate altercations have disastrous impacts on the more disadvantaged communities in the country.

The increasing frequency of heatwaves and their early arrival have enormous economic and health impacts, especially on agriculture-based communities, daily-wage laborers, and informal sectors such as rickshaw pullers, domestic helpers, and daily contractors, amongst others. In the past, it was only by mid-May that India would observe a surge in high temperatures, but summers are now arriving earlier. The premature onset of summer has resulted in sudden pressure on power demand and coal shortages that are pushing the country to face one of the worst electricity crises in decades. States such as Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Punjab have been observing power cuts for up to 8 hours a day that affect the local economies and the larger industrial sectors of the country. Moreover, the coupling of rising temperatures with industrial air pollution has worsened air quality in several cities like New Delhi and Bombay.

Earlier and prolonged summers are making the monsoon season more unpredictable, forcing farmers to adapt their production cycle every season. Where India was aiming to step up and aid the strained international supply chains caused by Russian war in Ukraine, it inevitably had to ban its wheat export due to an almost 50% major shortfall in yield from wheat crops. The north-eastern State of Assam has witnessed very heavy pre-monsoon rainfall causing floods all over the state. The overflowing of Brahmaputra River, one of the major rivers passing through India, has overrun close to 1500 villages and affected nearly 500,000 people. Although the National Disaster Management Authority of India (NDMA) has already started to rehabilitate the affected people, the sudden influx of mass migration to nearby cities has brought pressure on the local administration of these cities.

From mitigation to adaptation

While mitigation is important, as climate patterns continue to change, adaptation needs equal attention in India. Is India doing enough? In the city of Ahmedabad for example, excessive heatwaves in the year 2010 caused some 1,300 deaths, spurring the implementation of a specialized local heat health adaptation plan that helped prevent approximately 1,100 deaths each year since its launch in 2013. Experts have since called for more solutions such as the Ahmedabad Heat Health Adaptation Plan to be implemented across the country.

According to the CARIAA Working Paper, there are about 30 internationally-funded adaptation projects spanning a myriad of sectors such as agriculture, water, and disaster risk mitigation in India. Parallel to that several more are on the way to being finalized.

However, there are several obstacles to implementing existing and newly finalized adaptation plans. Many of the indigenous plans are being funded by standalone schemes that largely failed to curb the impacts precisely because the vulnerable communities – slums and daily wage earners that work outdoors – cannot afford to disengage from day-to-day economic activities even for a day.

Then there are cases where much more planning is required on adaptation. For example, the flash floods of 2022 in the State of Assam are not new: the region has been facing floods almost 3–4 times every year, according to the Water Resources Department of the Government of Assam. Episodes of flash floods every year have displaced millions of people and caused alarming environmental degradation such as coastal erosion leading to further internal migration. Despite having a dedicated disaster management plan, Assam has failed to pre-empt flash floods and other disasters to rehabilitate people much before they strike the mainland.

India has a varied climate around the country. Where the north is facing extreme heat waves, the northeast is experiencing flash floods. Therefore, the country needs specialized local programs to fight region-specific climate disasters, with short- and long-term solutions that protect people from health hazards while providing sustainable livelihood to vulnerable communities. This should be complemented with robust community rehabilitation programs, aggressive risk awareness programs, and locally tailored economic programs for daily-wage workers.

Climate mitigation is important, but definitely not enough in climate diverse countries like India. IPCC reports have substantiated enough that mitigation has to be complemented with adaptation to cut back the ongoing impacts of climate change to protect our future. India has already heavily invested to lead the way in climate mitigation; now it’s time that to invest more in climate adaptation.