India’s Roadmap to Decarbonization

As India moves forward with ambitious decarbonization goals, the focus is on harnessing power from renewables.

India has experienced numerous natural disasters related to climate change since 2010 such as the drastic weather patterns that led to unprecedented rainfall and flooding in states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh or the 2021 land subsidence crisis in Joshimath – a popular tourist town in the north-eastern state of Uttarakhand.

Authorities have initiated policies to combat this growing concern. During COP26 in the UK, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a target for the country to achieve net zero by 2070. The following year at COP27 in Egypt, India submitted its first Long-term Strategy for Low Carbon Development, providing strategic direction for the economy and individual sectors in support of that goal.

At the 2023 COP28 summit in the UAE, India, along with 130 countries, agreed on integrating agricultural emissions into their climate action plans. Furthermore, the Climate Finance Leadership Initiative (CFLI) India and Michael Bloomberg, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions and founder of Bloomberg and Bloomberg Philanthropies, announced climate finance solutions with the potential to mobilise over $6.5 billion to support India’s low-carbon, climate resilient development.

Over the next decade, these solutions will help mobilize private capital towards the $10.1 trillion needed to meet India’s net zero target by 2070.

Focus on solar and wind

In its move towards reducing fossil fuels and coal-dependency, the focus has been on harnessing power from renewables. India set a renewable energy (RE) target of 175 gigawatt (GW) by 2022 (which included 100 GW of solar, 60 GW of wind, 10 GW of biomass power, and 5 GW of small hydro power). Even though these targets are yet to be met, India’s policy-makers remain undeterred.

In December 2023, R K Singh informed India’s Upper House of the Parliament, the Rajya Sabha, that the country was on track to have 50 % of its installed power generation capacity from non-fossil sources by 2030. The country’s installed power generation capacity from non-fossil source is 186.46 GW, which is 43.82 per cent of its total installed capacity, he added. In 2022, the Rajya Sabha passed the Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill to mandate non-fossil sources of energy and establish a domestic carbon market in India.

As Pashupathy Gopalan, Co-Chairman and CEO of SunEdison, explains: “India’s renewable energy program and the effort that they have made to grow the RE sector is phenomenal. Moreover, the government is consistently shaping policies to ensure they grow better and indigenize the sector. The wind and solar deployment are a good example of what’s happened in India, and it has all been possible because of policy.”

The Draft National Electricity Plan 2022 highlights that India is planning to add significant solar and wind capacity by 2031-32, an increase of six and three times from 2021-22 levels, respectively. India has also been responsible for spearheading initiatives like the International Solar Alliance (ISA), conceived as a joint effort by India and France to mobilize efforts against climate change through the deployment of solar energy solutions.

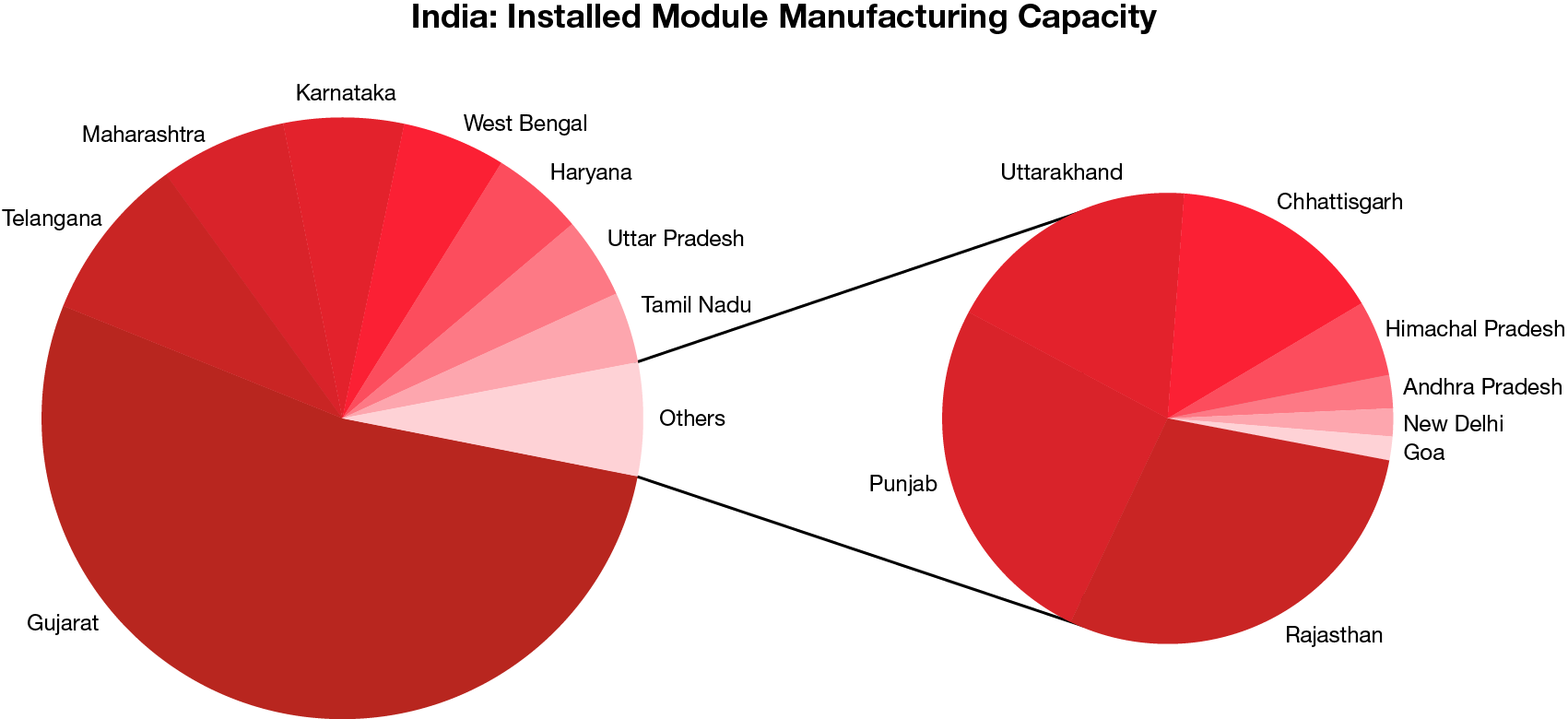

At a regional level, India’s state governments have ambitious plans to harness cleaner sources of energy. The state of Odisha aims to achieve 10 GW of renewable energy by 2030, and the state of Uttar Pradesh also released a policy for solar energy in 2022 which aims to achieve 16,000 megawatts (MW) of solar power projects by 2026-27. According to the Central Electricity Authority, the installed RE capacity in India increased from 115.94 GW in March 2018 to 172 GW in March 2023. Furthermore, 365.60 billion units of electricity were generated from RE sources across India during 2022-23.

But even as India prepares for faster integration of renewable energy sources in the electricity grid, certain challenges continue to daunt the sector. One of the biggest hurdles facing the solar and wind energy sector in India is the acquisition of land, which is complex and time-consuming, meaning that the process often leads to delays and cost overruns in solar and wind projects.

A leading solar developer, speaking on the condition of anonymity, believes that to meet the 450 GW renewables target (of which 300 GW is to be met by the solar sector alone), India needs to generate at least 40-45 GW of solar every year – for the next eight years – and wind needs to generate at least 30-35 GW.

Hiccups in the sunrise sector

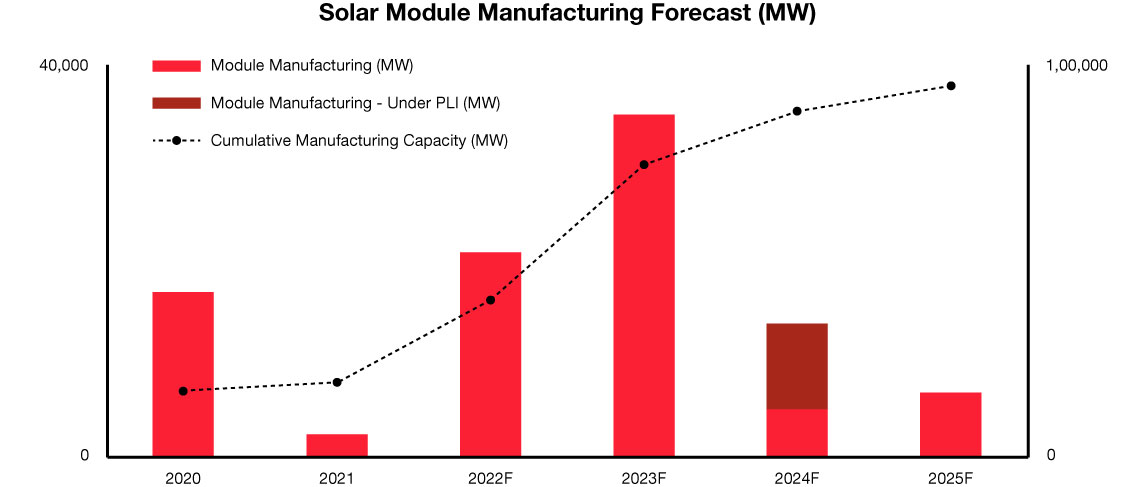

While India has already achieved about 62-63 GW of solar, one of the most pressing challenges is the lack of supply and steep costs. According to a solar developer, the asking rate is almost three and a half times that which India is doing (10-12 GW of solar every year) which is exacerbated by supply chain disruption and steep import duties of 25% on solar cells and 40% on solar modules.

The same solar developer says hurdles in the sector come from a combination of these high prices and the import restrictions enshrined by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE)’s Approved List of Module Manufacturers (ALMM). Designed to foster the domestic market, the list so far features no foreign companies, and it has its fair share of critics, who say it is overly restrictive.

In March 2023, the government waived the ALMM requirements for one financial year, meaning that solar power projects that start before 31 March 2024 can purchase modules that do not feature on the list of sanctioned providers.

However, as things stand at the time of writing, it is set to return after that time. The inability of the local manufacturing to ramp up module production to meet demand, coupled with tariff restrictions, is likely to impact price and availability of modules to local solar developers.

This limited capacity is now diverted for exports, as domestic manufacturers get a much better price realization for their sales to the US and Europe. The export of solar modules from India has increased by 644% compared to what it was in the year 2021 (as per India’s Ministry of Commerce).

The export of solar modules from India has increased by 644% compared to what it was in the year 2021.

Source: India’s Ministry of Commerce.

“If the numbers released by India’s Ministry of Commerce are scrutinized, there has been a phenomenal increase in the export of solar modules from April to November 2022 compared to the period from April to November 2021. While Indian exporters of solar modules are getting better prices in markets abroad, (touching $0.40/watt-peak [Wp]), in India, developers do not want to buy even at $0.29-0.30/Wp,” the solar developer adds. “This shows that whatever little is getting manufactured is all being exported and there is nothing available for the Indian market, which is putting India’s entire energy transition plan at high risk.”

There have been multiple petitions calling for the ALMM be delayed for at least a couple of years and for developers to be allowed to import. Initially applying only to utility scale projects, the ALMM clause has since been extended to private projects, rooftops and commercial/industrial clients. These are significant precursors to the kind of crisis that lies ahead for the solar sector in India – a veritable tariff and non-tariff wall that keeps out imports, exacerbated by the diversion of most domestic capacity to exports.

Indian manufacturers find the incentives given by the US government under the Inflation Reduction Act much more attractive than local incentives like the PLI and many have plans to set up manufacturing capacity in the U.S.A. rather than India.

Some experts believe that the market for the solar sector is moving away. Demand for tenders from the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) are low even though tariffs are low. This is because the price that solar used to command earlier in India is going down. Those who handle India’s electricity/power grid and the distribution companies want a steadier generation profile that is more in line with the load profile on the grid. According to a solar developer, this can be achieved only by hybridizing solar and wind.

Winds of hope

Unlike issues that are causing a hindrance to India’s solar sector, things are looking up for the wind energy sector in the country, even though the target of 60 GW of onshore capacity and 5 GW of offshore capacity set by the government by the end of 2022 was not achieved. An official press release stated that the installed wind energy capacity in India is 43.7GW as of 1 August 2023.

According to “Wind Energy Market Outlook 2023-2027” (a report jointly developed by GWEC India and Mec+), “India is a hub for wind manufacturing and has an existing annual capacity of 10 GW to 12 GW. Due to a slowdown in the domestic market in the last few years, this capacity has remained under-utilized. This is going to change as the domestic market is expected to see an increase in tender volumes.

Also, the country has an opportunity to translate the projected global supply chain crunch to its advantage by boosting manufacturing capacity in the country.” India, the report adds, is expected to install 21.2 GW by 2027. This installation rate could go up to 26.2 GW in the ambitious case and 17 GW in the conservative case.

While onshore wind power has been the backbone of India’s RE journey, a growing domestic and international appetite exists to tap into India’s significant offshore wind resource. By the end of 2022, the total renewable energy installed in India stood at 121 GW of total installations with wind contributing 35% of this, making India the fourth-largest wind market in the world, in terms of cumulative installed capacity.

The problem of a greenhouse gas molecule affecting the planet is global – one molecule (whether from Delhi or New York) contributes the same towards global warming.

Pashupathy Gopalan

The country needs accelerated deployment and commissioning of wind power projects if it is expected to achieve 140 GW of wind capacity by 2030 and advance towards the long-term goal of net zero by 2070.

For the wind energy sector in India, reverse bidding has driven prices so low that wind original equipment manufacturers were not able to take pricing pressures, leading to widespread distress in OEMs such as Suzlon, Regen and Inox. Global giants like GE and Siemens Gamesa have had financial viability challenges world-wide, and that has affected Indian operations as well. In a bid to revive the sector, the Indian government has done away with reverse auctions for wind. Now, they are simply closed bid tenders. This is expected to improve tariffs by reducing the incentive to quote irrational tariffs in reverse auctions.

New sources of energy and finance

Aside from solar and wind, the increased use of biofuels, especially ethanol blending in petrol, the drive to increase electric vehicle (EV) penetration and the increased use of green hydrogen fuel are expected to drive the low carbon development of the transport sector. India’s aspiration to maximize the use of electric vehicles and ethanol blending is likely to reach 20% by 2025, with a strong modal shift to public transport for passenger and freight.

When it comes to industries, with the Union Cabinet approving the National Green Hydrogen Mission, things are likely to improve for India in the near future. Pashupathy believes industries are the toughest to decarbonize because hydrogen is very important there. A switch to green steel and hydrogen-based boilers, for instance, will help decarbonize industries.

Pashupathy also suggests that finance is key. “In my view, the Indian government is doing a lot, though they can also think of ways, as in how India can attract the climate dollars that are available”. Since Western countries have huge budgets and funds for addressing climate change, it is imperative for them to invest in India. “There is a dearth of capital in India and for that to translate into reality, we need to awaken the world about our requirement for capital,” he explains.

Since Western countries have huge budgets and funds for addressing climate change, it is imperative for them to invest in India.

“If we examine the efficiency of decarbonization based on the dollar, I would say that India is one of the best places in the world for them to put their money. The problem of a greenhouse gas molecule affecting the planet is global – one molecule, whether from Delhi or New York, contributes the same towards global warming. What is possible is that $1 in India can go much further than in the US or Europe. Solar energy costs $2.50/watt in the U.S. while it costs $0.75/watt in India.”

Pashupathy stresses that the emphasis must be on getting consumers in India to spend money. “The U.S. government is giving investment tax credit to its consumers to adopt solar. Instead, it would be better if they gave the same financial support for Indian consumers, perhaps through innovative schemes working with Indian government, and reap the benefit. The problem of climate change is global and the efficiency to solve global warming is ignored by the Western governments in allocating funds.”

Going forward

Encouragingly, several measures are being taken to promote renewable energy in the country. Some of these include: the waiving of Inter-state Transmission System (ISTS) charges for inter-state sale of solar and wind power for projects to be commissioned by 30 June 2025; the declaration of trajectory for Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) up to the year 2029-30; and the setting up of mega renewable energy parks to provide land and transmission to renewable energy developers for the installation of renewable energy projects on a large scale.

On 22 December 2022, Minister of State for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Ashwini Kumar Choubey, told the Rajya Sabha that as per the updated NDC submitted to the UNFCCC in August 2022, India stands committed to reducing Emissions Intensity of its GDP by 45% by 2030 (from the 2005 level), and achieve about 50% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030.

According to the report “State of Solar PV Manufacturing in India” by Mercom India Research, India’s announced solar module manufacturing capacities exceeded 39 GW at the end of September 2022 and is expected to reach approximately 95 GW by the end of 2025. For the wind energy sector, as per the India Wind Power Market Report 2022, the cumulative installed wind power capacity stood at 40.36 GW in 2022 and is likely to reach 52.48 GW by Financial Year 2027.

India’s journey with renewables has been a long and eventful one. It was in 1985 that wind energy made an inroad into India, when the first wind mast was installed at Sultanpet in Tamil Nadu by the National Aerospace Laboratory, Bangalore. Several years later, the National Solar Mission was announced on 11 January 2010.

Some other counterparts of the RE sector (biomass and green hydrogen for example) are now being looked at as ones that can enhance the country’s journey towards a net zero economy. Despite the challenges that persist, there’s a renewed sense of hope as well – the hope that if the existing barriers to clean energy can be overcome, there’s no stopping India from becoming a game-changer, one that countries the world over can look up to and emulate.