Governance of Europe’s Waters

The European Water Framework Directive is a successful – although imperfect – model for international management and the protection of water supplies and natural water environments.

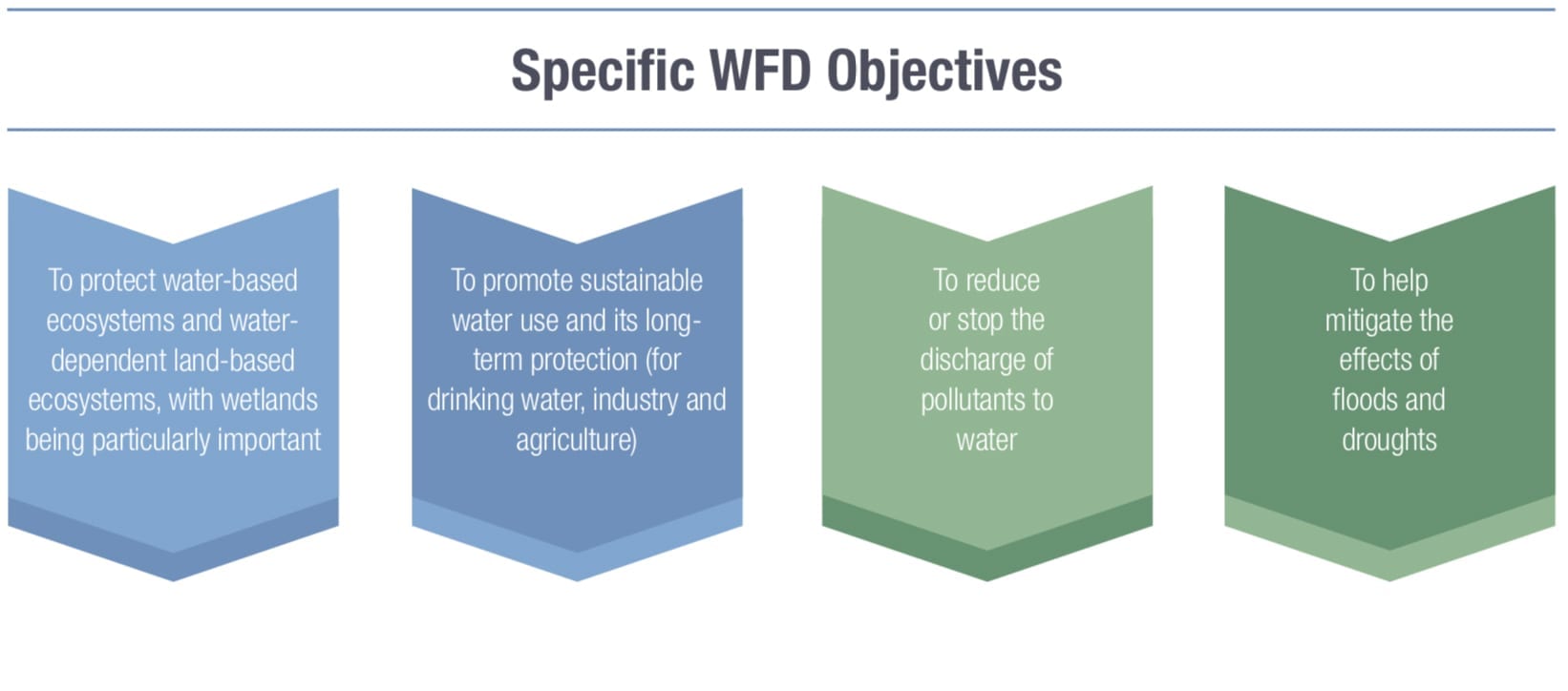

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is one of the most advanced and comprehensive examples of environmental legislation from the European Union (EU). Its stated purpose is: “to establish a framework for the protection of inland surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters and groundwater”. The primary objectives are to improve water quality and to protect water quality and availability across Europe. This has many additional benefits because of water’s critical role in the natural environment, for species protection, provision of safe and sufficient drinking water, economic development and for food production.

The publication of the WFD in 2000 was influenced by the increasing internationalization and complexity of water resources management and by a growing concern for environmental protection. The WFD represents a third wave in EU water policy development. The first wave, from the mid-1970s, was legislation to define drinking water standards and the need to protect water sources from pollution. The second wave, from the early 1990s, included increased controls on polluting emissions and activities (such as the Urban Wastewater and Nitrates directives). The WFD creates a more integrated approach from both a physical and governance perspective, as encompassed in the river basin model.

The most important characteristic of the WFD is that it establishes a governance structure for international and multi- stakeholder cooperation on the protection and sustainable use of water resources. As such, it provides a working example for other multinational regions of the world.

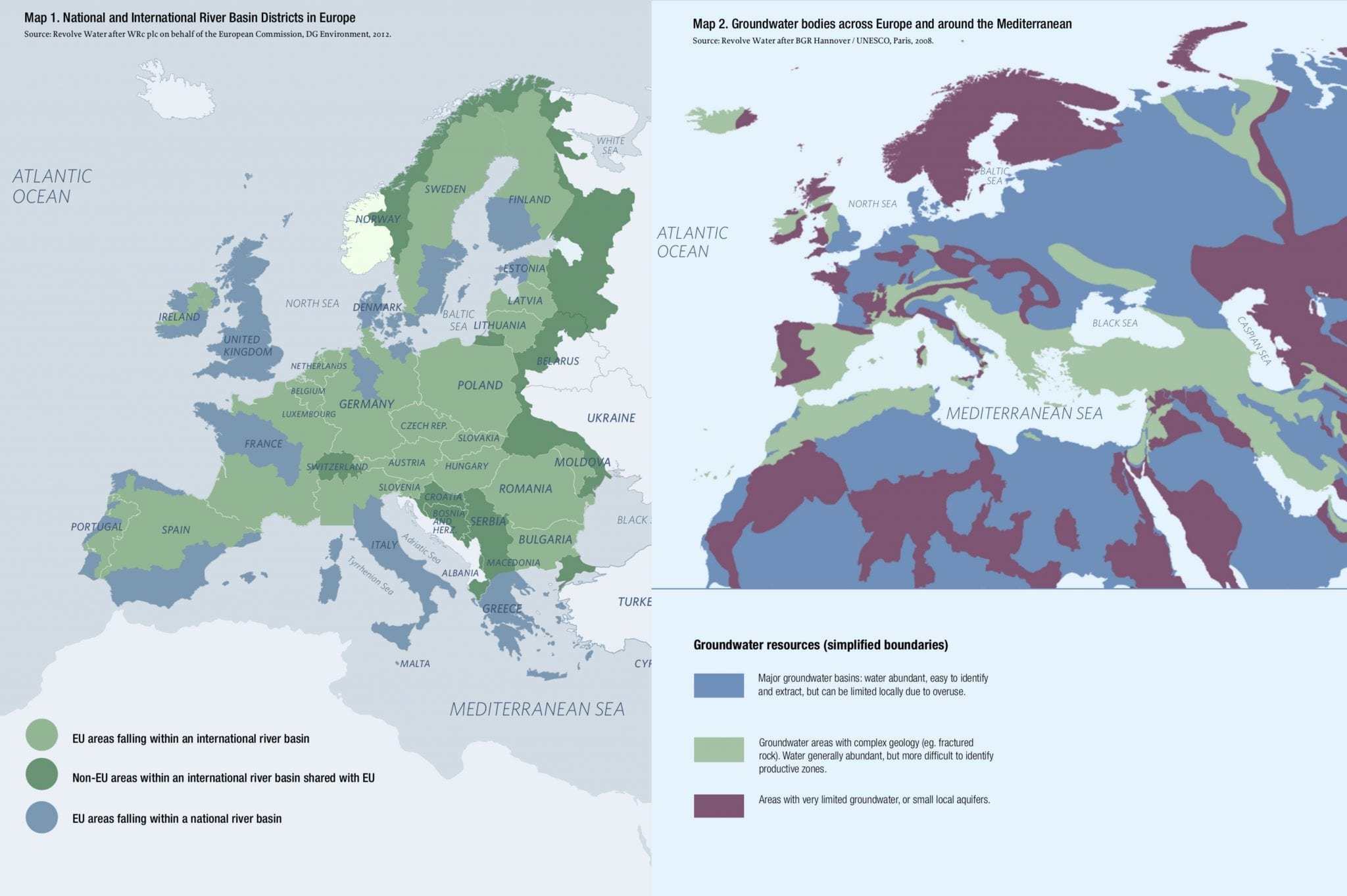

River Basin Management Plans form the core of the WFD. The whole of the EU is separated into River Basin Districts defined on the basis of natural geography rather than political boundaries. Each major river basin is defined by the area from which all surface water drains to a single point of outflow, such as a river mouth. Boundaries are defined by the topographical high (line of highest ground) between basins. A main river basin contains many smaller sub-basins of its tributary rivers and streams.

The river basin concept requires cooperation between different political areas within an EU Member State. For transboundary basins (crossing international borders), the WFD requires member states to cooperate and coordinate on water management. For basins extending to non-EU countries, the WFD strongly encourages cooperation between states. Around 60% of the EU land area lies within an international river basin (Map 1).

The WFD does not clearly define the mechanisms for international cooperation on transboundary river basins. Thus, it is for adjacent countries to agree a suitable mechanism. For example, for the Rhône Basin (extending from Switzerland into France), periodic formal meetings are held between the relevant French and Swiss water management organizations to ensure cooperation on common objectives and actions.

River basins are defined by surface water characteristics, but groundwater is also very important across Europe. For example, Denmark obtains nearly 100% of its water supplies from groundwater. Geological units containing groundwater, called aquifers, may extend over just a few tens of square meters, or over many hundreds of square kilometers. They can be as thin as 1-2 meters, or hundreds of meters thick. Surface water and groundwater bodies are often interconnected, with water flows between them, in either direction, at many locations. The boundaries of groundwater bodies often do not align with surface water boundaries, and many aquifers are transboundary (Map 2).

Most of these activities are carried out within the context of the defined river basins, and described in a River Basin Management Plan (RBMP). Such a plan must contain specific information, including:

A description of the river basin characteristics: Geographical extent, topography, land use, impacts of human activity and a description of water use.

Mapping of important features: Protected Areas, such as water bodies used for drinking water abstraction (surface and groundwater), species protection areas (aquatic, birds and others); recreational and bathing waters.

Monitoring programs: Establish and describe comprehensive programs to monitor water status (quality and quantity), to detect problems and to record improvements.

Program of measures: Define actions and measures to achieve the WFD objectives, using legislation if appropriate. A key example is the need to register and license all (except minor) water abstractions.

The Water Framework Directive includes and defines other important terminology and principles:

Stakeholder engagement: All interested parties, including citizens, should have an opportunity to be involved in the development of RBMPs.

Environmental objectives: Member states must define the criteria that define a healthy water body (‘good status’) in terms of quality, levels and flow regime. The Programme of Measures must then include actions to protect or achieve ‘good status’ for all important water bodies.

Priority substances and priority hazardous substances. The WFD established these concepts. A priority substance presents a significant risk to the aquatic environment and should be progressively reduced. A priority hazardous substance presents a higher risk and should be prohibited or phased out entirely. These groups include such substances as pesticides, biocides, metals, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and flame retardants. The lists are now, in fact, defined by a separate ‘Priority Substances’ Directive 2008/105/EC. There are 33 priority substances (or groups of substances) in total, of which 20 are ‘hazardous’.

Recovery of costs of water services: Member States are required to aim to recover the costs of all water services from water users, including environmental and resource costs, and in accordance with the polluter-pays principle. This is so far probably the least successful component of the WFD.

Control of pollution of groundwater: Specific additional measures are now defined in the ‘daughter’ Groundwater Directive 2006/118/EC.

Following the publication of the WFD in 2000, the first RBMPs were due in 2006, with a review and update required at six-year intervals. Initial environmental objectives were to be reached by 2015, with 2027 as a final deadline. The WFD is not a static directive: its progress and achievements are regularly reviewed.

To date, the WFD has certainly not achieved all its aims at the intended speed. By 2015, just over half of intended water bodies reached good status compared to the target of 100%. Also, inadequate levels of monitoring meant that 40% had ‘unknown’ status. Other criticisms are that some member states are not trying hard enough, and ‘exemptions’ are applied too widely and without sufficient transparency. The WFD allows a member state to exempt a water body from stringent objectives when heavily modified by human activity and when restoration costs are disproportionately high and when the water body provides an essential economic or social service such as for navigation, port facilities, drinking water storage, land drainage, etc.

While it is possible to criticize the incomplete and slow pace of implementation in some geographies, the EU Water Framework Directive has established, overall, a relatively successful program for the management, protection and improvement of the water environment across a multicultural, multinational continent with highly varied climate and geography. Good progress has been and continues to be achieved. As such, it is a model that other regions of the world could learn from.