7 Key Facts About Global Deforestation You Can’t Ignore

Deforestation continues to rise despite global pledges, putting biodiversity, climate stability, and livelihoods at increasing risk in 2025.

Forests worldwide support millions of livelihoods, stabilise the global climate, and are home to most terrestrial species, protecting the planetary systems that sustain life on Earth as we know it. However, global deforestation continues to rise, even as 145 countries vowed to end it by the end of the decade, and rainforests are being destroyed at ten football pitches per minute.

While progress in countries like Brazil and new technological and financial solutions provide hope, forests face unrelenting pressures from resource exploitation and emerging threats from a shifting geopolitical landscape.

In November 2025, UN Climate talks will take place in the Amazon for the first time, highlighting the vital role of rainforests, as well as their vulnerability in the face of climate impacts, economic pressures, and poor governance. Soon afterwards, the European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) will kick in to ensure commodities like soy, palm oil, and cocoa imported into the common market are not tied to land deforested or degraded after 2020.

As we enter the second half of a decisive decade to fix the planetary crisis, here is what you need to know about the state of the world’s forests, the key issues to watch in 2025, and the role of global environmental governance in keeping rainforests – and all the services they provide to humanity – standing.

1. The world is off track to end deforestation by 2030

Almost 6.4 million hectares of forests were destroyed in 2023 – an area the size of Latvia – and 62.6 million hectares were degraded as logging, road building, and wildfires expanded.

Deforestation has surged in Indonesia and Bolivia, driven by a change in political priorities and a global demand for commodities like nickel, paper, beef, soy, and palm oil.

Overall, destruction has worsened since countries backed the 2030 Zero Deforestation Pledge at the UN climate talks in 2021, and the level of deforestation in 2023 was almost 50% higher than progress towards this goal would require, according to a recent assessment produced by a group of research and civil society organisations. While complete data on tropical deforestation for 2024 is not yet available, overall trends appear to continue.

2. Nickel and pulp drive forest loss in Indonesia

Indonesia’s primary forest loss spiked 27% in 2023, reversing years of declining deforestation in the world’s third-largest rainforest. However, the figure is still lower than 2010’s levels, according to an analysis by the World Resources Institute, which points to wood pulp and nickel as the main drivers of the destruction.

The archipelago produces half of the world’s nickel, a key component of electric vehicles, solar panels, and other goods used for the green energy transition – although the nickel mining boom itself is often powered by highly polluting off-grid coal plants, further compounding the impacts of land clearance.

In parallel, the growing demand for wood pulp and derivatives like paper and viscose used by the clothing, packaging, and home goods industries is setting a major carbon time bomb. Around 40%, or 1 million hectares, of existing pulpwood plantations in Indonesia are on drained peatlands, a type of wetland that constitutes the largest terrestrial carbon store on the planet. Because peatlands take thousands of years to form, their destruction leads to irrecoverable carbon emissions and health risks from catastrophic fires.

In 2025, eyes will be on those trends, as well as on the new government’s pledge to continue a controversial agricultural programme and increase biodiesel production, which could drive the conversion of millions of hectares of forest into palm oil fields.

3. The Amazon sees lower deforestation amid record droughts

The Brazilian Amazon saw deforestation fall 30.6% between August 2023 and July 2024, continuing a three-year trend and marking the lowest annual loss since 2015. The decline is attributed to the policies of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s government, including stricter enforcement against land grabbing and illegal logging.

However, the feedback loops between deforestation, record-breaking droughts, soaring temperatures, and wildfires still threaten to irreversibly turn nearly half of the world’s largest rainforest into a savannah by 2050, upending water cycles and climate patterns across the Americas and beyond.

The Amazon is in the second year of a historic drought, and Brazil suffered its worst fire season in 14 years in 2024. This trend could continue as global warming and erratic rainfall make parts of the western Amazon up to 30 times more fire-prone than pre-industrial times. Fires degrade the forest and are often a prelude to land clearing, as does infrastructure expansion.

Despite progress in curbing illegal activities, the Brazilian government has sparked a heated debate with plans to pave an 885-kilometre highway cutting through old-growth forests. The road was opened in the 1970s by the military dictatorship but soon fell into disrepair. Rebuilding it, critics say, will open the door to unprecedented levels of deforestation in one of the best-preserved areas of the Amazon.

Elsewhere in the basin, the forest is also under pressure. In Bolivia, home to 11% of the rainforest, setting fires to expand the agricultural frontier, gold mining, and drug trafficking infrastructure saw primary forest loss rise by 27% in 2023. According to Global Forest Watch, this is the highest figure on record for the third consecutive year – and another example of the impacts of environmental crime in contexts with poor oversight.

4. Subsistence fuels deforestation in the Congo Basin

The Congo basin, which spans six countries in Central Africa, is home to the world’s least explored and best-preserved rainforest. Although it comes second in size after the Amazon, it absorbs more carbon dioxide per hectare than its counterpart, harbouring the planet’s largest tropical peatland – a vast complex with 30 billion tonnes of carbon locked in the soil.

Most of the rainforest is in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which lost half a million hectares in 2023 alone. Deforestation in the region is still largely a result of shifting cultivation, charcoal production, and informal and illegal logging – all of them reflecting a combination of poor governance, lack of livelihood alternatives, and population growth.

Globally, nearly six billion people use non-timber forest products, and 70% of the poor depend on wild species for food, energy, medicine, and income, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). In its 2024 report on the state of the world’s forests, the FAO also notes that global roundwood demand could increase by up to 49% between 2020 and 2050, potentially exposing international supply chains to more illegal timber, which now accounts for 15–30% of production.

5. Climate change increases vulnerability to fire and pests

Human-induced climate change makes the planet’s forests more vulnerable to stressors such as pests and wildfires. According to the FAO, fires hit harder and more often, touching areas previously spared. A case in point is boreal forests, vast expanses of deciduous trees and conifers that stretch around the northern tip of the globe and account for nearly one-third of the world’s forest area.

Boreal fire used to account for about 10% of global carbon dioxide emissions. But in 2021, its share skyrocketed to nearly a quarter of total wildfire emissions – a record scientists believe may not stand for long as protracted droughts and heatwaves are becoming a new normal. In 2024, the first half of the boreal summer saw severe wildfires in Alaska, Canada, and Eastern Russia, with vast quantities of smoke travelling across parts of North America and Eurasia.

Additionally, climate change is making forests more vulnerable to invasive species, insects, and pests that affect tree growth and survival. Creatures like pine wood nematodes – microscopic, worm-like parasites – are inflicting damage in native pine forests in Asia and Europe, and areas of North America are projected to suffer extensive damage due to insects and disease by 2027. Deadwood fuels wildfires, compounding their threat to lives, property, and ecosystems.

6. The EU’s Deforestation Regulation nears implementation

The European Union’s consumption is responsible for around 10% of global deforestation, with palm oil and soy accounting for more than two-thirds of this forest loss, followed by commodities like wood, cocoa, coffee, rubber, and cattle.

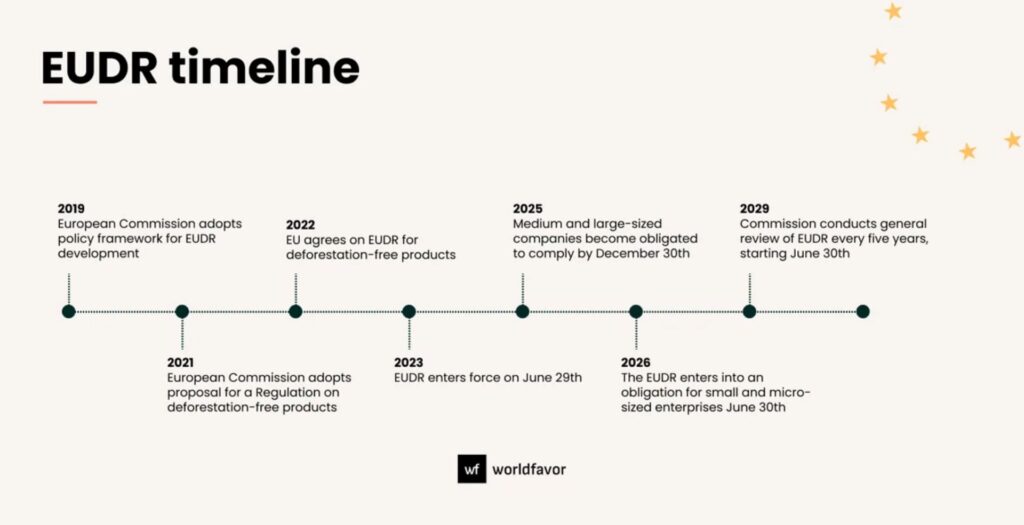

The EUDR, adopted in 2022 to ensure that products imported into the common market have not contributed to forest loss anywhere, will roll out on 30 December 2025, after the EU Parliament voted to postpone it one year. The delay provides importers and producers more time to adapt to the new requirements, including mandatory due diligence and geographic data collection, but has been controversial.

The European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), adopted in 2022 to ensure that products imported into the common market have not contributed to forest loss anywhere, will roll out on 30 December 2025.

The investigative non-profit Earthsight, for instance, claims that representatives of the European People’s Party (EPP), which has been pushing to postpone and soften the regulation, got more than 1.7 million euros in donations from companies linked to forest destruction, suggesting the influence of industry lobbies in efforts to put the EU on the path to more sustainable trade policies.

Other potential obstacles for EUDR implementation are the insufficient oversight of certification bodies, upon which importers tend to rely to make procurement decisions; the risk that deforestation-linked products are redirected to less regulated markets; and the difficulty of smallholder farmers in producer countries to comply with more stringent standards.

Economic and political trends are also set to play a role in forest conservation globally: commodity prices; the strength of the US dollar; fiscal policies and subsidies in producing countries; and the political dynamics in nations like Brazil, Indonesia, and the United States.

However, with penalties for violations ranging from product bans to fines, the landmark EU policy looks to play its part in halting deforestation and forest degradation worldwide, incentivising sustainable land management, and encouraging responsible consumption.

7. The future of forests calls for better governance and land management

Technological advances and innovative finance – from public-private alliances to nature-for-debt swaps and biodiversity credits – provide new tools for monitoring and funding forest conservation.

For example, the World Resources Institute (WRI) and Meta have produced a global AI-powered, high-resolution map of tree canopy heights outside dense forests. Trees in drylands, farms, and urban environments make up more than one-third of tree cover on Earth but are largely absent from traditional forest data sets. The data, WRI says, is already being used to monitor small-scale restoration projects throughout Africa, which can help them access finance.

Another highlight is NASA’s GEDI mission, which has resumed operations to capture 3D images of forest structures through equipment attached to the International Space Station. The data will provide further insights into the health of rainforests and the extent to which the Amazon is reversing its role as a major carbon sink due to deforestation, forest degradation, and climate change.

Despite the importance of technological advances, the future of forests will be largely determined by governance, global production and consumption patterns, and international cooperation around capacity, enforcement, and funding for forest countries.

Experts cite the following as their priorities: enacting strong regulations – the EUDR is a step in that direction – instead of relying on corporate volunteer commitments to cut deforestation; reducing excessive consumption levels; and realising the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and women, as well as providing alternative livelihoods to the millions of people who depend on slash-and-burn agriculture, charcoal production, and informal logging.

Other key goals are the transformation of agrifood systems, which are the top driver of deforestation and water consumption globally; investing in land use planning and sustainable land management; and beefing up law enforcement – especially, as criminal networks increasingly combine illegal logging with drug trafficking and mining in places like the Amazon. The race is on.