Cold War at the Bottom of the Sea

Norway, considering itself one of the world’s most eco-friendly countries, is well on its way to becoming the first country to welcome deep sea industrial mining.

On 9 January, the Norwegian parliament’s vote to approve deep-sea mining passed by an overwhelming majority – 80 votes in favor, 20 against. Norway, considering itself one of the world’s most eco-friendly countries, is thus well on its way to becoming the first country to open part of its seabed to industrial mining.

The intended Norwegian ‘exclusive economic zone’ comprises 281,000 square kilometers. The mining will occur between 1500–4000 meters deep, in perfect darkness illuminated only by creatures producing bioluminescent light.

The ocean depths – including the floor – are home to some of the least explored ecosystems on the planet and on many counts, the most delicate. The area designated by the Norwegian government is the natural habitat of a myriad of animal species, including several types of whales. According to scientific estimates, the zone could also be home to thousands of undiscovered species, which means we have no idea what might be at risk.

I.

The mostly unexplored sea depths are already heavily affected by climate change, pollution, and excessive fishing. In the opinion of oceanologists and marine scientists, the extraction of metals and minerals in the name of tackling the climate crisis could further imperil deep-sea ecosystems.

Part of the area marked for mining lies within the Norwegian continental shelf, while another part lies in neighboring international waters, whose floor falls within Norwegian jurisdiction. One part of the mining zone is the Arctic Archipelago Svalbard – seen by Norway as its exclusive economic area, despite a 1920 international treaty stipulating shared use with Russia, Great Britain, and Iceland, along with 48 other countries.

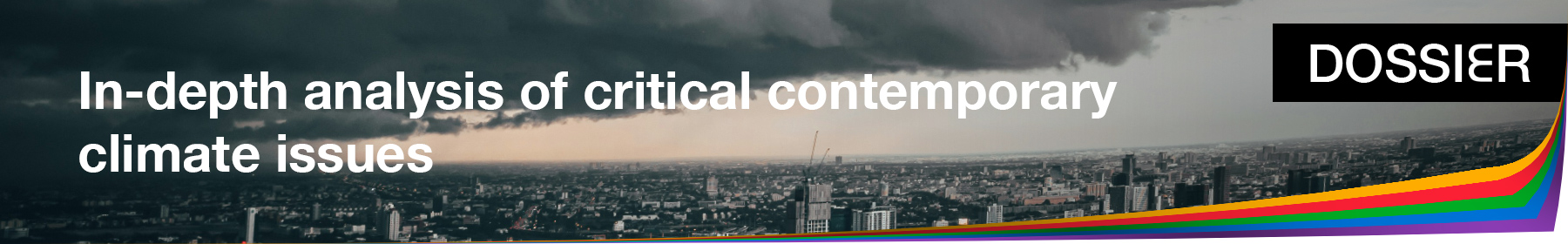

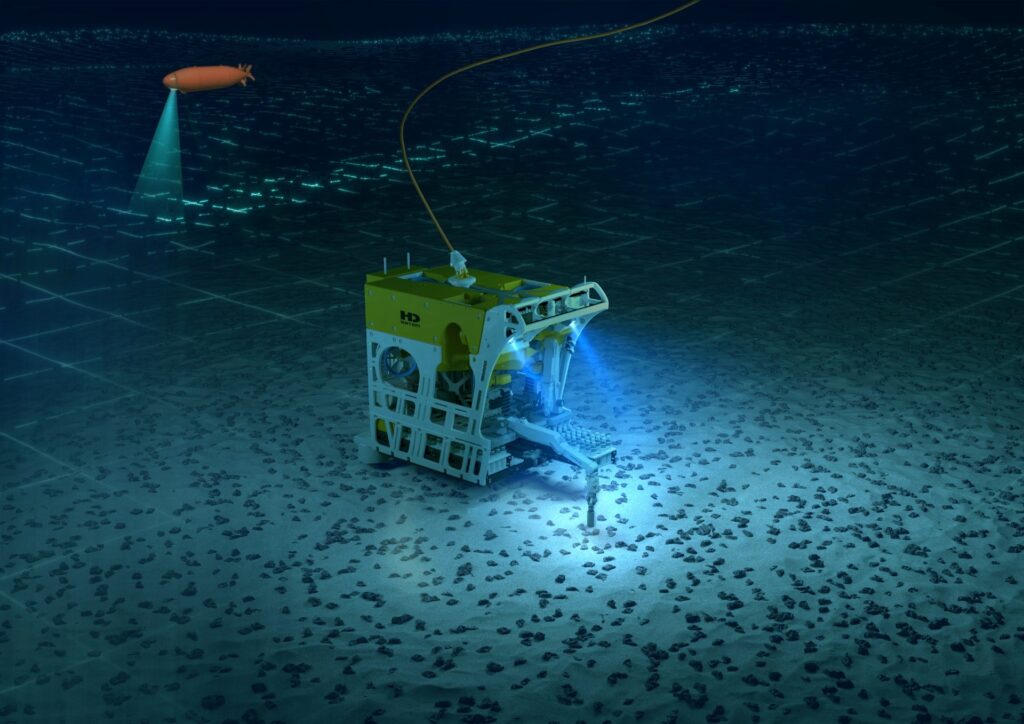

Norwegian companies plan to utilize the seabed for the extraction of cobalt, copper, zinc, magnesium, nickel, and several rare metals. The rare metals are located in the manganese crust of underwater mountains and the vicinity of active or extinguished hydrothermal vents.

The key argument of the deep-sea mining industry to win over politicians and investors is that seabed mining is vital for the green transition. According to this view, the production of renewable-source and electrical mobility technologies will require almost limitless quantities of choice metals and minerals.

The brutal tampering with the planet’s least explored, yet extremely sensitive ecosystem is thus presented as the only viable path to decarbonization.

A Norwegian Day of Shame

“We need to cut 55% of our emissions by 2030, and the rest of our emissions after 2030,” Astrid Bergmål, state secretary in the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, told Mongabay. “The reason for us to look into seabed minerals is the large amount of critical minerals that will be needed for many years,” Bergmål continued. She also pointed out deep-sea mining will only take place if the Norwegian government determines that it is conducted “in a sustainable way with acceptable consequences.”

Norway is of course far from the sole example. The Cook Islands, Japan, New Zealand, and Namibia are only a few of the countries also updating their deep-sea legislation.

The Japanese government has already built the first ship for harvesting underwater metals. The venture is set to kick off by the end of the decade. Last November, the Japanese authorities declared that the designated area contained enough cobalt for 88 years and enough nickel for 12 years of Japanese needs.

China, on the other hand, owns the greatest number of licenses for the exploration and mining of the Pacific seabed. Russia and South Korea own many licenses as well – like India, which intends to set up its own exclusive area for deep-sea mining.

The feeling that the industry is plagued by a great deal of environmentalist opposition can be deceiving. The opposition is present only in the environmentally sensitive regions of the Western world, and even there the masses are not clamoring to abort the mission.

II.

The Norwegian branch of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is convinced that the parliamentary decision in favor of seabed mining fails to meet even the minimal legal standards, thus prompting the WWF to sue the government.

“Norway’s decision to proceed with opening vast ocean areas for destructive mining represents an unprecedented governance scandal,” CEO of WWF–Norway, Karoline Andaur, said. “Never before have we seen a Norwegian government so blatantly disregard scientific advice and overlook the warnings from a united ocean research community. If this decision is not contested, we accept that politicians can break the law and manage our resources blindly. This would establish a new and dangerous precedent for how impact assessments are conducted by both the current and future governments.”

Twenty-six countries have thus far called for a temporary moratorium on the project, including France, Mexico, Denmark, and Great Britain. They were joined by more than 800 scientists from 44 countries who decided to write an open letter to the Norwegian authorities.

“The sheer importance of the ocean to our planet and people, and the risk of large-scale and permanent loss of biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecosystem functions necessitates a pause of all efforts to begin mining of the deep sea,” the letter stated.

Calls for a moratorium have even been echoed by global corporations like BMW, Microsoft, Ford, and Google. The European Investment Bank went on to remove investments in sea-mineral mining from its portfolio due to their potential “climate and nature impacts.”

Though Norway is not a member of the European Union, January saw the European Commission issue an appeal to Oslo to ban deep-sea mining until more is known about its likely effects, and until it is proven that mining will not harm maritime ecosystems. In February, the European Parliament unanimously passed a resolution highly critical of Norwegian plans.

III.

“Seabed mining could endanger some of the globe’s most sensitive and vulnerable areas,” said Peter Haugan, policy director of Norway’s Institute of Marine Research and director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen. “The day Norway decided on this course of action was a very sad day for our country.”

Haugan is convinced the decision of the Norwegian authorities is at variance with the law. “Nowhere near enough scientific evidence about the likely consequences has been collected beforehand.” According to him, politicians acted much too rashly. The respective licenses will be awarded soon, and the applicant companies do not possess the capacity to explore the area set apart for seabed mining properly.

“It is absolutely too soon for issuing licenses!” Haugan was firm. “We really know very little about the ecosystems at such depths and also about the seabed itself. There’s just too much that we don’t know! And the same goes for the animal species that can be found there. We’re talking about an extremely sensitive and fragile environment we do not understand. The risks are enormous. The mining is planned to take place at significantly deeper levels than those of our current oil and gas boreholes, where the risks are at least somewhat understood!”

Hogan believes that some 10 years would be needed for a sufficiently serious exploration of deep-sea ecosystems. The same goes for a serious examination of long-term mining risks.

Haugan fears that the Norwegian example will likely embolden other countries with similar ambitions. He also believes the Norwegian government might be rushing the process of issuing licenses to strengthen its control over the Arctic, especially the Svalbard archipelago. “Territorial concerns might be playing an important role. Although that’s currently mere speculation on my part.”

Haugan expects the process of seabed exploitation to be met with increasing resistance from the environmentalist community. He is also doubtful of the venture’s economic viability. “Tremendous investment will be needed, the kind even big gas-and-oil companies like the Norwegian state company Equinor are wary of. For the big investors, there are currently still too many unknowns.”

In the Name of the Green Transition

The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) recently stated that Norway’s decision represented “an irrevocable black mark on Norway’s reputation as a responsible ocean state.”

An EJF report claims deep-sea mining is not needed for the energy transition. According to the report, humanity’s current climate goals could be met through a combination of new technologies, circular economy, and recycling. In this manner, our demand for metals and minerals could be reduced by 58%.

The EJF is firmly convinced the potential benefits of deep-sea mining do not outweigh the certain damage to the environment.

As previously mentioned, Greenpeace called the January parliamentary vote a Norwegian day of shame. “It is embarrassing to watch Norway positioning itself as an ocean leader while giving the green light to ocean destruction in Arctic waters,” elaborated Greenpeace Norway’s Project Manager Frode Pleym.

His views are echoed by Haldis Tjeldflaat Helle, Deep-Sea Mining Campaign Lead at Greenpeace Nordic.

“The government seems to be in a great hurry,” she told me in Oslo. “Its haste in issuing licenses suggests it wants to get it done as soon as possible. The tender was out at the end of April. The final date for applications was 21 May. With all the national holidays in between, the tender was only open for eleven workdays. In the oil industry, the normal period is two months.”

According to Tjeldflaat Helle, the unusually short window for application suggests that the government knew the companies were already prepared. She also believes the government is rushing the process for next year’s parliamentary election, with the current coalition aiming to ‘cement’ the decision to open a great part of the Arctic seabed for exploitation.

At any rate, three start-up companies have applied for a research license. Our sources believe the Norwegian government might announce its decision in early 2025. After that, the legislation requires 90 days for consultation and public debate. The first licenses should therefore be issued in the first quarter of next year. This means the actual deep-seabed exploration could begin in second half of 2025.

IV.

While talking to the representatives of the fledgling huge industry, one gets the impression of overwhelming confidence.

“Their confidence is only on the surface,” Haldis Tjeldflaat Helle cautioned. “I’m sure they’re aware of how much guesswork is at play. There are just so many unknowns! Especially with regard to the functioning of the equipment they are developing.”

Like many of her peers, Tjeldflaat Helle is profoundly disturbed by the fact that the mining companies neglected to include a plan for long-term exploration of the seabed and depths where numerous unknown animal species reside. “You normally need 8–10 years just to classify and describe a new animal species. And down there, there are bound to be so many! Ninety-nine percent of the area designated for mining is unexplored. The government claims the extraction will be undertaken with utmost environmental responsibility. But how can they say that with so little information?!”

For Tjeldflaat Helle, the argument that the venture is part of the green transition doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. “The green transition should be serious about preserving the environment, not blindly striking off for completely unexplored ecosystems! This doesn’t make any sense, which is proved by the unanimous response from both the Norwegian and international environmentalists. Deep-sea mining poses a tremendous risk to biotic diversity. It is also a huge risk from the climate change perspective since the ocean serves as a carbon sink.”

Deep-sea mining poses a tremendous risk to biotic diversity. It is also a huge risk from the climate change perspective since the ocean serves as a carbon sink.

Greenpeace Nordic’s Deep-Sea Mining Campaign leader is also not convinced of the project’s economic viability. She is quick to warn that the findings of different geological surveys hugely contradict each other.

At the same time, mining the Arctic seabed would be different than mining the Pacific – much more aggressive. According to Tjeldflaat Helle, it would entail plenty of new equipment. “Let’s not forget that parts of the designated area are located as far as 500 kilometers from the nearest shore. Working in the far-off Arctic waters will be extremely demanding, and the limited reach of the rescue helicopters is only part of the reason why it’ll be very dangerous. Enormous investment will be needed just to secure the safety of the workforce.”

With each new day, Tjeldflaat Helle is further convinced that the Norwegian government’s approach to deep-sea mining is that of the most irresponsible among stockbrokers. “I must repeat that the entire environmentalist community is extremely worried. Such a momentous project should be based on transparency and responsibility. Thus far, this has not been the case. Even some of the most basic questions we addressed to the decision-makers have not been answered. And yet they’re about to start handing out licenses!”

V.

With so little support among environmentalists, how is it even possible that the venture has been greenlit? It is certainly curious that deep-sea mining only seems to be supported by politicians.

“It is a matter of the specific Norwegian context,” Tjeldflaat Helle attempted an explanation. “The prime minister, Labour Party leader Jonas Gahr Støre, is a great supporter of the project. He’s got a lot of political capital invested in it. Before the parliamentary vote, there was a lot of strife between various ministries. Seabed mining is a controversial issue even within government ranks. The only ministry firmly in favor of the project was the Ministry of Energy. It’s terrifying that the idea was passed by the parliament anyway since it suggests the will of the prime minister was the decisive factor. On the other hand, Norway is the land of oil and gas. The leaders of these industries wield a great deal of influence in our society, both of the formal and informal kind. When you look at which companies have decided to apply, you can safely say that a part of the mentioned industries decided to hop on the ‘mining train.’ But there’s so much we simply do not know. Both environmentalists and journalists find it very hard to reach the people who are making these decisions. They usually just pass us on to some minor bureaucrat or other.”

Every day, Tjeldflaat Helle grows increasingly horrified by the lack of transparency, given that Norway likes to pride itself as one of the most democratic countries in existence. “Perhaps the most chilling of all is that the government decided on a public stance according to which the negative response from the European parliament was caused by environmentalists spreading misinformation.”

VI.

Many Norwegian environmentalists believe that authorities in Oslo naively expected the story of deep-sea mining to pass under the public radar. Yet the response from environmentalists was swift and forceful – both at home and abroad.

“I hope this whole thing can still be halted,” Tjeldflaat Helle confided. “At first, the licenses in question will only mandate exploration. The mining permits are conditioned by proof that the process would not be too harmful to the environment. There’s still a chance that the government decides to take a step back. And the next government could also reverse the changes to the legislature. It is solely a matter of political will.”

Soon, Greenpeace intends to take a sailboat full of scientists to the designated Arctic area to conduct their own research. The trip could be viewed as the start of the campaign against deep-sea mining, and it will be followed up by sailing along the Norwegian coast to raise public consciousness.

Toying With the Future

A succession of Norwegian governments has been considering the idea of deep-sea exploitation for at least the past eight years. The situation turned serious with the passing of the Sea Mineral Act in 2019.

“The act is merely a framework which can be bent to many purposes,” I was told by marine biologist Kaja Lønne Fjærtoft. “In 2020, Norway then passed an act opening the designated area. The act necessitates a holistic estimation of the effects on the environment, the economy, and the community. Only if the estimation is favorable are the politicians allowed to decide on the next steps. This is also backed by the Sea Mineral Act, which states that in case of insufficient data, further study is required.”

As someone who used to work for the Norwegian Ministry of Energy, Lønne Fjærtoft is intimately familiar with the functioning of both the Norwegian fossil industry and Norwegian bureaucracy. Some 30 months ago she chose to join the WWF, where she now leads the campaign against deep-sea mining.

The previous Norwegian government set apart a 600,000-square-kilometer area for seabed mining. A large part of the area is not within the Norwegian exclusive economic zone, where Norway is entitled only to the resources on the sea floor while everything above the floor is considered international waters. These waters are currently host to fishing boats from various countries, many of which have already expressed fervent opposition to Norwegian mining intents.

There is little doubt that deep-sea mining would disrupt the normal functioning of international waters in more ways than one.

VII.

The Norwegian Environment Agency (NEA), a governmental body, responded to the ambitious nature of the mining plans by notifying the decision-makers that two years was not enough for the preparation of a sufficiently sound risk evaluation.

Little to no data is available for almost the entire designated area. “There are parts where the exact sea depth hasn’t even been measured,” Lønne Fjærtoft explained. “The government’s analysis confirms that, ‘due to the holes in our knowledge,’ holistic risk estimation is currently impossible. This statement alone legally requires them to initiate further study, but they haven’t done so. They did, however, reduce the potential mining area to 281,000 square kilometers. The reason? A biased analysis indicated this reduced area was rich in desirable minerals. The analysis of natural resources by the Norwegian Offshore Directorate was conducted without public consultation. This caused a huge revolt among numerous environmentalist organizations, which saw the governmental approach as completely irresponsible.”

The NEA dismissed the said analysis as invalid since it failed to fulfill certain European criteria. According to the agency, the analysis also failed to meet the demands of the 22nd article of the Sea Mineral Act, which lists the criteria for a valid analysis of the effects on the environment. The agency further declared the analysis to be in breach of cautionary principles, and breach of Norwegian biodiversity legislation.

“It was the most forceful statement by the agency in its entire history,” Lønne Fjærtoft related at the WWF’s Norwegian branch office in downtown Oslo. “They actually used the word ‘illegal’! Even the state-owned oil company Equinor started urging the government to caution.”

WWF Nordic and other environmentalist organizations expected their revolt to goad the authorities in Oslo toward further research. Yet this didn’t happen. Quite the contrary. In January, the government put the project to a vote and the parliament passed it by a large majority.

Many of the activists and scientists I talked to, including Kaja Lønne Fjærtoft, believe that the Members of Parliament (MPs) have been misled – that they had not been presented with all the relevant information. They might have been duped by the government’s insistence on how it was principally a matter of exploration. Several sources told me that some of the MPs have since grown to regret passing the proposal but only in private. None have thus far tried to publicly atone for the blunder.

Behind closed doors, according to our sources, the foreign minister Espen Barth Eide called the deep-sea mining project the greatest smudge on the Norwegian public image in history.

“Before the vote was taken, some of the MPshad never even heard of seabed mining,” Lønne Fjærtoft explained. “The government tried to keep the topic under everyone’s radar, and the MPs simply passed what they’d been told to pass.”

Lønne Fjærtoft also shared her fears about what might happen in case the project is halted. Will the licensed start-up companies, after having invested enormous amounts of money, decide to sue the state for having been misled?

“The private companies interested in deep-sea mining are driven purely by financial motives,” Lønne Fjærtoft is convinced. “Sustainability doesn’t concern them in the slightest. Our message to the government was: You don’t know what you’re doing! The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research clearly stated that 99% of the designated area was completely unexplored. So we tried to press the government to perform further studies. For a year and a half, we pointed out huge inconsistencies and even breaches of the law. In the end, we decided to sue the Norwegian state. It was a hard decision, but we had to consider that our government’s actions could be used as a precedent somewhere else.”

The WWF first warned the government, hoping this might dissuade the decision-makers from further action. All such hopes were in vain. The government officials simply dismissed all of WWF’s claims. So, in May environmentalists finally filed the lawsuit in earnest. The law requires the courts to conduct the first round of interrogations within six months.

Only a few days after the lawsuit was filed, the government launched the licensing process. One therefore must wonder what happens if the lawsuit is successful. Can the project be stopped after the licenses have been awarded and seabed exploration is well on its way?

“We don’t know,” Lønne Fjærtoft replied. “It is not only a matter of domestic legislature; it is also a matter of international law. You need to understand this is the worst decision any Norwegian government has ever made regarding the environment. The oceans are key to our survival. Risking their safety means toying with the future!”

Scientists are concerned that mining the seabed – with its underwater mountains, where hot magma frequently bursts from hydrothermal vents into icy cold water – could cause enormous damage. The mining would cause the rise of huge amounts of sediments, which is likely to disturb the routines of deep-sea populations of bacteria, algae, sponges, whales, and dolphins, to name but a few species.

Norway’s neighboring countries are also likely to be affected. The same goes for the entire Arctic, including its shores. According to current plans, Norway’s deep-sea mining would be more invasive than that of the Pacific.

The speed the Norwegian government is imposing on the project is extremely worrying to environmentalists. Despite the years she spent as an insider, Lønne Fjærtoft admits she does not fully understand the haste. “The project is most aggressively pushed by the Ministry of Energy, more specifically by the energy minister himself.”

The leader of the campaign against deep-sea mining also pointed out the tremendous efforts Norwegian officials have invested in mollifying the international community. Norway has recently sent a delegation to Kingston, Jamaica, where the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is situated. The delegation consisted of three representatives from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, two from the Ministry of Energy, one from the Offshore Directorate, and none from the Environmental Agency. The visit’s official purpose, of course, was to ensure “the highest environmental standards.”

The proponents of the dee-sea-mining project are interested in preventing an international ban. While such a ban does not seem very likely, Oslo’s diplomatic offensive on the ISA could still be construed as an attempt at strategically pre-empting the international governing body.

The ISA functions within the scope of the United Nations and is set to pass its final verdict on deep-sea mining in 2025. A regulation for deep-sea mining is also being prepared. As of 2024, the practice is not forbidden in international waters. The initiative for the regulation was provided by the small island state of Nauru, one of the ‘sponsor states’ for the recipients of deep-sea mining licenses.

The Geopolitical Background

Once the tape recorder was turned off, many of my sources were eager to talk about the overlooked and hard-to-prove reasons why a part of the Norwegian political and economic elite is bending itself backward to secure control over the natural resources in the Arctic.

The reasons, many believe, are mostly geopolitical.

Norway aims to strengthen its position in the northern reaches of the globe not only because of the abundance of natural resources, but also on account of rapidly escalating tensions between the USA and Russia. Norway shares its Arctic border with Russia, while the Svalbard treaty is loose enough to leave room for various interpretations. The last time Norway publicly expressed the conviction that it is entitled to a more generous interpretation was in 2007 – when the current prime minister Jonas Gahr Støre was foreign minister.

The current situation is highly reminiscent of the Cold War. Back then, like today, a highly militarized Norway was considered one of NATO’s key members and territories. “The timing is no coincidence,” Norwegian sources kept telling me. The Northern territories themselves are considered just as vital as the resources located below the seabed.

To understand the geopolitical context of deep-sea mining, the following information might prove useful. Three of the five armament companies receiving the largest financial investments from the European Commission – through the Act in Support of Ammunition Production and European Defense Funds – are seated in Norway: Nordic Ammunition Company (Nammo), Nammo (Raufoss), and Kongsberg (Defense and Aerospace AS). Through the Rheinmetall Nordic AS company, Norway is also connected to Germany’s Rheinmetall, the largest recipient of European defense contracts.

In short, Norway is well on its way to becoming the EU’s main arms-producing partner.

VIII.

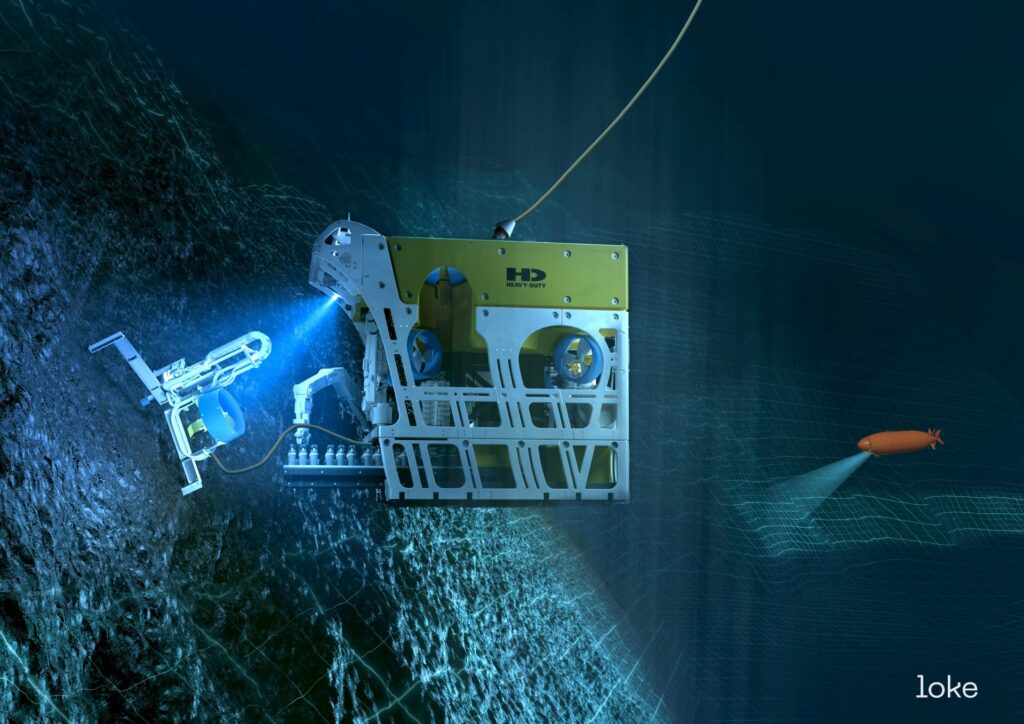

Kongsberg, half-owned by the Norwegian state, is the single largest investor in the Norwegian deep-sea mining company Loke. Kongsberg is the world’s greatest producer of far-range military systems. It is also the strategic partner of Canada’s The Metals Company, the strongest player in the global market for deep-sea mining equipment.

The Canadian start-up is seen as the most advanced when it comes to technology development and seabed mining. At the end of 2022, it performed a test excavation of the first 3000 tons of rocks and stones from the seabed. This year, The Metals Company is set to apply for a license to begin mining on an industrial scale.

Walter Sognnes, CEO of Loke, is a geophysicist by education. After more than three decades in the oil industry, he spent the past 20 years working as an entrepreneur focusing on oil dealings in Norway and Great Britain. Five years ago, he decided to hop on the green transition train, like many people who used to work for the oil industry.

In Sognnes’ own words, the reason behind his career switch was his realization of “the interesting convergence between the oil and gas industries and potential deep-sea mining projects.” So, he co-founded Loke.

“At first we decided to focus on Norway,” Sognnes recalled. “We were able to attract a number of powerful investors – the smart-money kind, the ones who bring money and new technologies. Along with our partners, we’ve been developing mining technologies and technologies for seabed exploration aimed at causing minimal damage to the environment.”

Through registration in Great Britain, Loke already obtained two licenses for the exploration and mining of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located in international waters between Mexico and Hawaii. The zone’s seabed is believed to be the globe’s richest in metals and minerals. The Norwegian company was able to secure the two licenses by purchasing a company previously owned by American armament giant Lockheed Martin. In the process, Loke turned itself into one of the main license-holders in the humongous Clarion-Clipperton Zone, covering 4.5 million square kilometers, which could become the Saudi Arabia of underwater mining.

On 21 May, Loke sent a proposal to the Norwegian government, listing the Arctic areas deemed most suitable for mining.

“The locations for exploration and potential mining are to be chosen this autumn,” Sognnes pointed out. “Things should move relatively fast, given that the Norwegian legislation on minerals is almost a copy of the legislation governing the oil and gas industry. But the said industry developed over several decades, while the deep-sea mining industry is only being formed. I guess it means we’ll just have to adapt as we go along.”

Norwegian Cognitive Dissonance

Sognnes believes the first exploration licenses will be issued at the beginning of 2025.

This is how he describes his motivation for entering the deep-sea mining business: “Norway has a long history of talk about sooner or later having to shut down the oil and gas industry and look for alternatives. But we can’t just close down our biggest industry! The oil engineers were supposed to seek new and more green forms of employment. But what kinds of jobs would those be, exactly? Very few specific proposals were offered. Given our vast pool of excellent cadres, this sparked my idea of creating a seabed-mining company. I want to help build this brand-new industry, which has a lot in common with the oil industry. The green transition will only be possible if sufficient resources for its technologies can be secured.”

In Sognnes’ view, the Norwegian deep-sea mining industry doesn’t need the mining industry when it comes to exploration, excavation, and transport of resources to the surface. All the necessary know-how and equipment are in the hands of the oil industry.

“It is very different than on the surface,” Sognnes continued listing the arguments for seabed exploitation. “If we want to keep the Western world competitive with China in the context of the green transition, we have to create our own supply line. And a proper one, covering all links from mining to processing to manufacture of end products. China currently controls most of the mines and the natural resources within them. Due to environmental and business reasons, the West almost entirely gave up on mining and processing, sort of relocating or transferring them to Asia…So now we’re far behind on the natural resources front. And the demand is certain to only rise and rise.”

IX.

“The West has exceptionally high standards of environmental protection, which is excellent. We also have a ‘not in my backyard!’ mentality. This mentality is part of the reason why most of the mining was done far away from our eyes and minds. That we didn’t seem to mind. But when images of digging out cobalt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo reach the public, there is a huge outcry,” Walter Sognnes dissected the cognitive and moral dissonance at play all over the Western world.

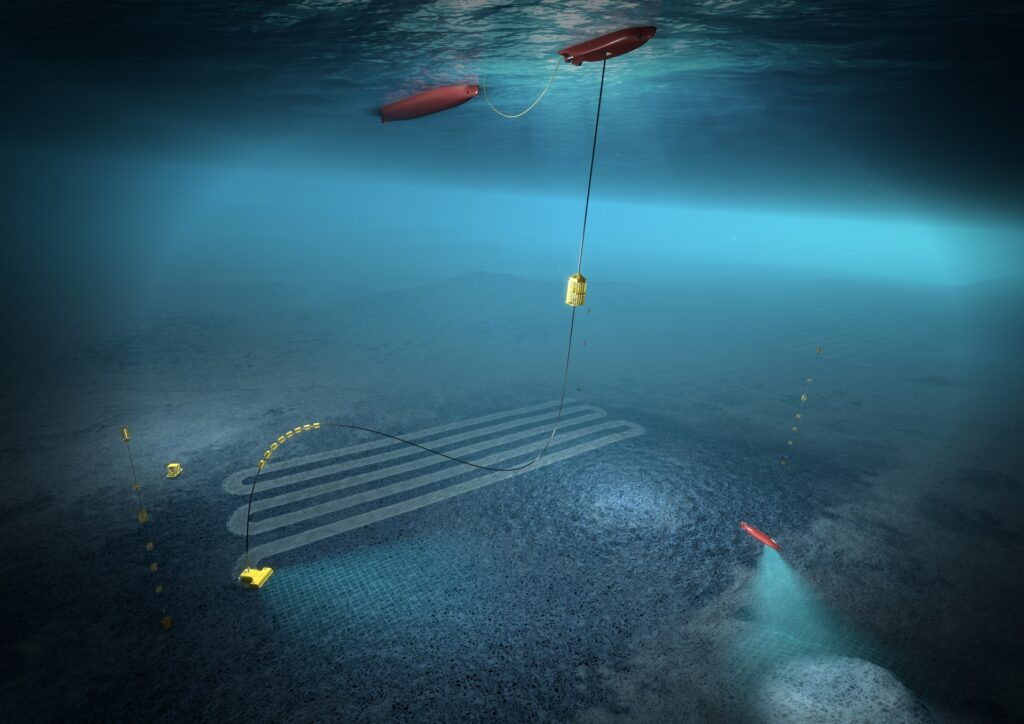

The CEO of Loke is aware of the strong domestic and international opposition to aggressive incursions into the natural world. Especially into its unknown reaches. According to Sognnes, the exploration phase should be rather easy, technologically undemanding, and cheap. It is not difficult to locate minerals and metals in the manganese crust. The same goes for finding the areas where mining should prove commercially viable. The technology used by the oil and gas industry – such as crewless submarines and naval drones – is already available.

Sognnes believes the exploration phase, including marking the seabed and furthering our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems, should take between three to five years.

“By then, both the environmental and mining plans will be ready. Should the government confirm these plans, the production process could begin two years later. The most demanding task is to set up an efficient production process with minimal impact on the environment. Once the resources are brought to the shore, we will need the infrastructure to process them. This is currently our greatest challenge, as the said infrastructure doesn’t exist. What there was, we closed down. Which means we have to build from scratch. Today, most of the minerals are processed in China. But if we ship them over there, we’ll have achieved nothing. The Western world needs to react as soon as possible,” Sognnes was clear.

In his view, the Chinese monopoly is a serious geopolitical and economic problem.

“We are quite vulnerable. Whether we like it or not, our green transition is firmly bound to our mining industry. I don’t see us opening new mines in densely populated Europe and the USA. Our best mines have been closed for decades. So, what are we supposed to do? This question is best aimed at geologists. And the answer they came up with lies on the seabed with its abundance of metals and minerals. We of course need to do everything in our power to optimize the equipment to protect nature. If we can achieve that, and if we can gain the people’s trust, then we’re looking at the birth of an incredibly beneficial new industry,” the CEO of Loke addressed critics.

I think political and economic elites see deep-sea mining as the continuation of the oil and gas industry, which is slowly running its course. The oil bureaucrats need a new project. And they’re using the green transition as an excuse.

Gytis Blaževičius

The Norwegian entrepreneur understands the project’s success would stimulate development in competing countries like China, India, and Russia, where he believes the authorities will have little sympathy for environmentalist concerns. “The green transition doesn’t only mean ‘unplugging’ us from fossil energy sources. It means replacing the fossil industry with the mining industry. This is a sort of a paradox.”

So, what is his answer to the public’s justified concerns about potentially irreparable damage to the environment? What sort of assurances can he offer?

“We are acting in accordance with legislation and the Norwegian parliament’s plan,” Sognnes replied. “We are strictly beholden to the precautionary rule. We are also not the ones who get to decide whether the industry happens or not. But we need to start somewhere. We need to at least gather as much information as possible to fill the gaps in our understanding. Scientists are always learning. I am well aware we’ll never know everything. But we should strive to know enough to make the correct decisions. The seabed contains everything we need for the green transition, save lithium. There is currently a moratorium on mining the seabed until adequate regulation is passed. To those who oppose us, I would say: please allow us to fill the gaps in our knowledge. And on that basis, we can decide.”

If all goes to plan, Sognnes expects mining in the Arctic Circle to begin after 2030.

X.

“I think political and economic elites see deep-sea mining as the continuation of the oil and gas industry, which is slowly running its course. The oil bureaucrats need a new project. And they’re using the green transition as an excuse,” I was told by Gytis Blaževičius, who runs the Norwegian NGO Natur og Ungdom (Young Friends of the Earth).

“For 10 years, the people tasked with managing natural resources within governmental structures were unaware that the Ministry of Energy was preparing for deep-sea mining. The whole thing happened furtively, in silence…” continued the 23-year-old activist.

Blaževičius, too, marvels at the breathtaking speed with which the process of issuing licenses has been unfolding, given Norwegian bureaucracy’s fame for its glacial pace. Blaževičius is also baffled by the confidence of the representatives of the ‘future great industry,’ since every single applicant company is still in its start-up phase. What little we know shouldn’t exactly embolden investors to come running.

“Even the costs of exploration will be astronomical. A couple of years ago, the University of Bergen performed single research in the area marked for mining. The bill was one million euros. To explore the entire area will take billions. And an awful lot of time. There’s no guarantee that an abundance of metals and minerals is waiting for us down there,” Blaževičius related.

He added that, from the current outlook, he finds it hard to believe the deep-sea mining industry will prove viable. “I am pretty confident in predicting the project will turn out to be a dud.”

XI.

While pushing for seabed mining, the Norwegian government is also issuing new permits for oil and gas projects in the North Sea and Barents Sea. For a few years, this was seen as controversial even in Norway – a country fuelling its green transition with the export profits of the fossil industry.

As of August 2024, the public hasn’t reacted with any force to the government’s plans to launch the deep-sea mining industry. The common man and woman know virtually nothing about the seabed mining project. Blaževičius explained this was not merely due to the non-transparent methods of the government, but also the fact that the Norwegian public prefers to leave environmental issues to NGOs. Norway boasts five million inhabitants and 24 million members of NGOs. This means that, on average, every citizen is a member of almost five different NGOs. In many ways, these organizations have replaced civil society.

In Blaževičius’ opinion, the response of the Norwegian public has been rather weak because of the project’s far-off nature, both geographically and temporally: “Norway made a lot of money off the Ukrainian war and the resulting spikes in oil prices. So, we started marketing ourselves as Europe’s safe and reliable source of gas. And all of a sudden, fossil energy is no longer as controversial as it was! This brought fresh wind to the sails of the oil and gas lobby, and many new permits for rigs are being handed out.”