Bringing Back Nature for People and Planet

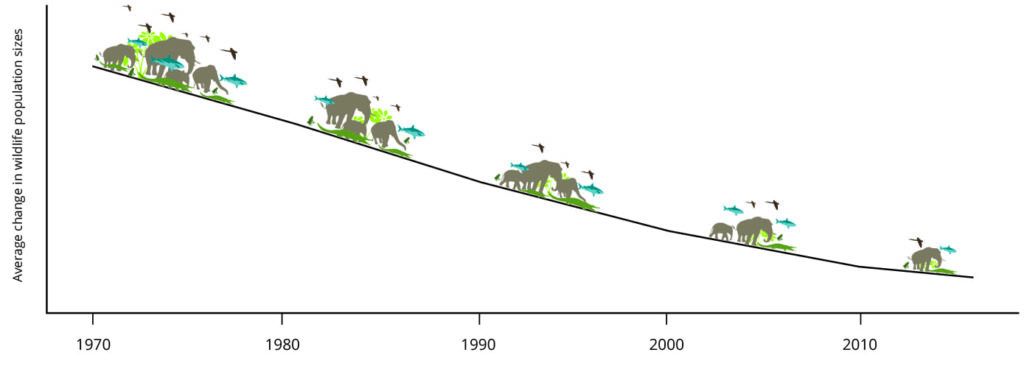

For centuries humans have plundered the natural world to cash in on short-term benefits, significantly altering three-quarters of the Earth’s land and two-thirds of the ocean. Since 1970 there has been, on average, a decline of 68% in wildlife populations and this catastrophic loss of biodiversity is exacerbating already dangerous levels of climate change[1]. From exchanging natural forests for agriculture monocultures, to choking rivers with hydropower dams and scraping the seabed to extract fish from the depths of our ocean, nature has suffered immensely, and Europe is no exception.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on the toxic relationship between people and nature. As humans destroy and modify natural ecosystems, the likelihood of outbreaks of zoonotic diseases – those which jump from animals to humans – rises [2]. And it is not just about physical health either. Our general well-being and the health of our planet are inextricably linked. Already now, the degradation of our natural world due to human activities is having a negative impact on the well-being of at least 3.2 billion people [3].

The facts are truly harrowing, but thankfully, solutions are available and one fundamental antidote is nature restoration.

Nature-based solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural and modified ecosystems in ways that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, to provide both human well-being and biodiversity benefits.

International Union for Conservation of Nature

By protecting and restoring nature and well-functioning ecosystems we can tackle the twin crises of biodiversity loss and climate change, help to prevent the future emergence and spread of diseases and at the same time reinvigorate economies and societies. Large-scale nature restoration is an investment that yields a range of benefits, such as flood protection, water retention and prevention of wildfires. Nature-based solutions, such as the restoration of natural forests and rewetting peatlands, could provide more than one-third of the climate change mitigation efforts that are needed before 2030 – although rapid greenhouse gas emissions reduction remains essential. On average, the benefits of restoration are ten times higher than the costs [4].

An EU law for nature restoration

As part of the European Green Deal and the EU 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, the European Commission will propose legally binding EU nature restoration targets in 2021 to restore biodiversity and degraded ecosystems, in particular those with the most potential to capture and store carbon and to prevent and reduce the impact of natural disasters. WWF welcomes the proposal as a key tool to contribute to halting and restoring biodiversity loss and for climate change mitigation and adaptation, but the devil will be in the detail.

With only 10 years left to avert dangerous levels of climate change and biodiversity loss [5], time is of the essence. WWF is calling on the European Commission to set a target of 15% of land and sea to be restored by 2030 both at the EU and the Member State level. The targets must also be rapidly implemented, have immediate impact on the ground, result in permanent change aiming to restore high quality and resilient nature and bring about a significant improvement compared to the starting condition of the ecosystem. Nature-based solutions and contribution to climate change mitigation and adaptation must also be at the center of the new law.

Equally as important is the full involvement of local communities. WWF firmly believes including communities and local stakeholders in nature restoration projects will be key to success. From the forests of Greece to the mires (a type of peatland) of Estonia, our latest publication Nature Restoration: Helping People, Biodiversity, and Climate showcases the range of benefits that have been garnered from nature restoration. Below a few case studies are outlined, but there are many more to discover from all across Europe.

The EU must restore:

*sea area to be adapted to EU 27 EEZ

– 15% land and sea

– 650,000 km2 of land

– 1,000,000 km2 of sea area*

– At least 25,000 km free flowing rivers

A community calls for restoration, Parnitha, Greece

Mount Parnitha, which is located 30 km north of Athens, Greece, is a forested mountain range seen by citizens as a symbol for the capital. The forest, part of a National Park and the EU’s Natura 2000 network, is home to the Greek fir tree (Abies cephalonica) and to several mammals, birds, plants and herbs species, including protected animals like wolves and red deer, and rare local flowers such as the bellflower (Campanula celsii).

In 2007, the forest was decimated by megafires with 4,900 hectares of Mount Parnitha burned, destroying 62% of the Greek fir trees [6]. Fortunately, Greek forest law obliges the Forest Department to survey an area after a fire and declare it an area for restoration. In reality, restoration work is not always carried out due to a lack of political will or budget constraints.

The local community acted fast and called on its government to carry out the restoration work. Within ten days, a huge protest was organized via social media. Thousands of people wearing black protested in front of the Greek Parliament, calling on politicians to act.

In 2008, the restoration of the Parnitha forest began. WWF Greece, the Forest Department and the Management Authority of the National Forest Park of Parnitha trained nearly 2,500 volunteers, who assisted with the forest restoration. The Forest Department also contracted expert forestry companies to restore the burnt area.

Fast forward 13 years and a mix of natural and active restoration has brought life back to Mount Parnitha. 1,374 hectares were restored naturally by banning grazing, hunting and logging. In the actively restored area, 193,000 black pines, 800 downy oaks and 209,778 Greek fir trees have been planted and more trees are still growing in the Parnitha forest nursery due to be planted in the coming years. In addition, 1,913km of anti-erosion works have already been completed since the first year of restoration.

The Parnitha forest restoration project has been a success, largely spurred on by community engagement, political pressure and the legal obligation of post-fire restoration in Greece.

“With the excellent cooperation of the competent services and the support of all stakeholders, we expect the maximum result, which is the gradual afforestation of Parnitha and its restoration to its original state,”

Dr. Georgios Karetsos, The President of the Administrative Board of the Management Authority of the National Forest Park of Parnitha.

Restoring wetlands for biodiversity and climate

Acting as major carbon sinks, the mires of Estonia provide climate change mitigation and boost biodiversity by creating habitats for important wetlands species such as the western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), the moor frog (Rana arvalis) and dragonflies (Leucorrhinia). Mires also contribute to water retention and regulate the water balance, which directly impacts the surrounding land and protects local communities and other habitats further downstream. Despite the clear benefits for biodiversity, climate and people alike, mires are becoming rare and degraded across the EU. In Estonia, areas have been severely damaged by drainage for agriculture, forestry and peat extraction, and as a result of lowering water levels, trees and shrubs expanded, causing the typical Estonian fen mosses to disappear.

In 2015, the LIFE Mires Estonia project coordinated by the Estonian Fund for Nature turned the fate of these degraded mires around. The project aimed to restore degraded mires to a favorable conservation status and to increase biodiversity by improving the living conditions of several wetland birds, frogs and butterflies. To allow the area to naturally re-wet, around 300 km of drainage ditches were closed and outflows stopped.

The benefits of mire restoration for climate and biodiversity are still being quantified. However, an analysis of a peat sample area that was restored showed that, in the 30 years since peat extraction ended, the drainage of peat in the area has led to the approximately 1,100 tons of carbon being emitted, and the amount of peat that has been degraded is almost 3,600 tons. The re-sequestration of the same amount of carbon back into a wetland of similar area would take approximately 300 years. Additional analysis is required in regard to whether the carbon sequestration function recovers and at which rate but various studies have indicated that carbon loss can decrease by 50% in less than ten years in recovered or restored areas compared to the situation prior to intervention. In addition, water retention will be improved which benefits the local communities downstream.

The restoration of the Estonian mires is a perfect example of how bringing nature back will contribute to solving both the biodiversity and climate crises.

37 years of successful cooperation with local fishers

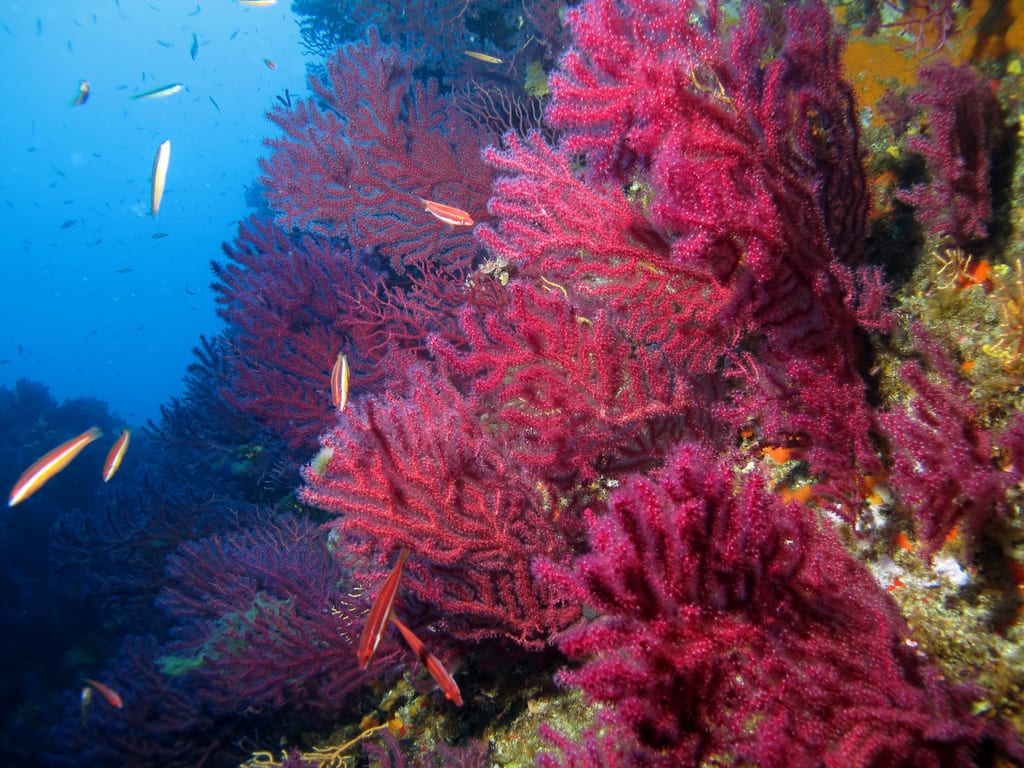

The Côte Bleue marine park is located close to Marseille in France and is part of the Natura 2000 network. It was created in 1983 to enable the sustainable development of small scale fishing activities, to protect the environment, for scientific research and to raise public awareness about environmental issues. The coastal zone managed by the park is made up of extremely rich and diverse ecosystems, including virtually all the different Mediterranean species and habitats.

The park aims to protect specific habitats and species, including Mediterranean coral reef habitats, fish such as the dusky grouper and Posidonia seagrass meadows. Seagrass meadows are highly biodiverse ecosystems that host 25% of all Mediterranean species. The meadows also protect the coast and therefore local communities, reduce erosion and account for more than 10% of the total amount of ocean carbon storage. Their ability to rapidly store organic carbon into sediments, where it remains ‘locked’ for long periods of time [7], is essential in mitigating climate change.

The Côte Bleue park contains two strictly protected areas: Carry-le-Rouet and Cap Couronne, where all kinds of fishing, dredging, anchoring and scuba diving are forbidden. In the rest of the park, all activities, including recreational sports such as sailing and sea kayaking, are permitted. As part of the restoration work, between 1983 and 2004 the park installed 4,884 m3 of two types of artificial reefs: production reefs and protection reefs. The production reefs were submerged on seabeds devoid of natural habitats to attract, shelter and support flora and fauna. The protection reefs were deployed to act as a barrier against illegal trawling and created 17.5 km of physical barriers. These reefs protect the most fragile elements of the ecosystems.

Crucially, the active involvement of stakeholders in the Côte Bleue project was a key component of the marine park’s success story. The involvement of fishers in management and monitoring has proven effective in ensuring sustainable artisanal fishing activities. Several studies have shown the tangible results of this co-management, with the ‘reserve effect’ (i.e. the increase in fish size, density, biomass as well as species richness[8]) being demonstrated by the return of the dusky grouper as well as the brown meagre fish in no-take areas. The fishing yield has also increased sevenfold since the creation of the no-take reserve of Couronne. As a result, fishers have adopted a more positive view of management measures in the area, as these species also leave the no-take areas and become available to the fishing community. The wider community has also benefited from educational discovery courses, which are organized to explore the marine area and local fishery.

Overall, the Côte Bleue marine park has increased the number of local species and the quantity and size of fish. The park demonstrates how Marine Protected Areas can deliver good ocean governance and benefit local communities and economies.

“As a scientist with a lot of field experience, I am convinced that for the marine environment, the best restoration measure is to protect the area from harmful activities and then mother nature can recreate biodiversity and restore herself,”

Eric Charbonnel, Marine biologist and Scientific Supervisor, Côte Bleue marine park.

The opportunity ahead for people and planet

Across Europe, nature restoration has brought a multitude of benefits for local communities, biodiversity and climate. In the midst of the biodiversity and climate crises, immediate large-scale restoration will be a fundamental tool in tackling both emergencies, bringing added socio-economic benefits.

The European Commission now has the opportunity to kick-start restorative actions by proposing a strong nature restoration law, including ambitious and legally binding targets both at the EU and Member State level. It must also be a key part of Europe’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic to increase the resilience of our societies, economies, and to prevent the future emergence of zoonotic diseases.

WWF therefore calls on the European Commission to urgently propose a strong and ambitious nature restoration law with a target of 15% of land and sea and for Member States to adopt and implement this as a priority.

References

- [1] WWF and Zoological Society London (2020): Living Planet Report (2020) – Bending the curve of biodiversity loss

- [2] WWF (2020): The loss of nature and rise of pandemics

- [3][4] IPBES (2018): Summary for policymakers of the assessment report on land degradation and restoration.

- [5] IPCC (2019): Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems

- [6] All data comes from the Management Authority of the National Forest Park of Parnitha and the Forest Department of Mount Parnitha

- [7] Fourqurean JW, Duarte CM, Kennedy H, Marba N, Holmer M, Mateo MA, Apostolaki ET, Kendrick GA, Krause-Jensen D, McGlathery KJ, Serrano O (2012) Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock.

- [8] Sarah E. Lester, Benjamin S. Halpern, Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, Jane Lubchenco, Benjamin I. Ruttenberg, Steven D. Gaines, Satie Airamé, Robert R. Warner (2009) Biological effects within no-take marine reserves: a global synthesis

- [9] Piante C., Kapedani R., Hardy, P.-Y., Gallon S. 2019. Safeguarding Marine Protected Areas in the growing Mediterranean Blue Economy. Recommendations for Small-Scale Fisheries. PHAROS4MPAs project. 52 pages.