Finnish Forests in the Uruguayan Pampa

The world is made of paper and with paper you buy the world: A reportage on the Finnish forestry industry and its unsustainable forest management – in 10 acts.

Eucalyptus and its transformation into pulp have been a form of veiled economic, social, environmental, and political invasion used by the Finnish multinational company UPM in Uruguay: To what extent can a company change the present of a nation and influence its future with promises that never come through?

I.

“They rent bodies and then discard them, and they think they can do the same with the land,” says Loreley Urbeldz. A nurse and mother from Paso de los Toros, a city of 13,000 inhabitants located in the heart of Uruguay, Loreley has a strong voice, is blonde and bright as the winter sun, and to supplement her income, she occasionally moonlights as a taxi driver.

In 2022, the year when the Finnish multinational UPM set up its second plant in Uruguay on the banks of the Río Negro, the calm and deep river that runs through the city, Loreley was the trusted driver of many women, including Colombians, Venezuelans, Cubans, and Dominicans who worked at City Night, a famous brothel located in Centenario, a small town near Paso de los Toros.

Right: Aerial view of recently harvested eucalyptus monoculture in Orgorroso, Paysandú, Uruguay. Photos: Dahian Cifuentes

One night she received a message with a location: “Come now, my friend is being beaten.” Loreley, as she recalls, rushed to the lodging of the international workers of the company:

“A foreigner was jumping on the legs of a sex worker. They told me to take the girl and forget about everything in exchange for money, that they had cocaine and wanted to avoid problems with the police. The girl, with a Caribbean accent, was in bad shape. While waiting for the ambulance, I gave her first aid. After they took her to the health centre, I went on to file a report,” she says.

And Loreley continues explaining that “the commissioner and several police officers threatened me. Foreigners who work for UPM are untouchable. You can not do anything against money. They are in Uruguay but protected by other laws. It is as if they had bought this land and we were the foreigners.”

UPM’s presence has significantly impacted local communities, altering their social and economic dynamics. In Uruguay, there are two UPM plants capable of producing 3.4 million tons of pulp per year. Pulp is a fibrous lignocellulosic material prepared by chemically, semi-chemically or mechanically producing cellulosic fibres from wood, fibre crops, waste paper, or rags.

Their arrival was promoted as the panacea of progress which, if it came, was to put in check the communities where they settled. UPM 2 is the voluminous, smoky, and grey landscape around which Centenario revolves: it is its skin, its entrails, its spirit, its voice.

A voice that arises for whoever wants to hear it, perfectly and clearly, like when truth breaks through the consciousness of the denier: the world is made of paper and with paper you buy it. UPM not only produces the base of the paper used by half the world, but also uses it to get everything it needs: silence, for example.

UPM not only produces the base of the paper used by half the world, but also uses it to get everything it needs: silence, for example.

It was precisely this silence that the Uruguayan director and playwright Marianella Morena found when she arrived in Centenario with the aim of investigating the industry’s effect on both people and the environment. UPM had everything under control, and the only thing that stood out in the vast silence, besides a colossal chimney, was the cash register of City Night.

Months later, when Marianella had already assimilated and unraveled everything she heard and saw in her visits to Centenario, she wrote: “Colonization and letting oneself be colonized can be a shared exercise.” This phrase serves as a preface to the play Metsä Furiosa, a production that stages the exploitation of the human body and its close link to the exploitation of the land in a Uruguayan town of 1,500 inhabitants, where a Finnish company is building the world’s largest pulp plant.

II.

Matti Liimatainen scans the discs of hundreds of stacked logs waiting to be transported to the UPM factory in Kaukas, 220 kilometres from Helsinki, near the Russian border. When he finds one that convinces him, he takes a wooden stick from his bag and starts to patiently count the rings.

From the core to the bark: “112 years.” The forest where Liimatainen stands belongs to Tornator, one of the companies with the most forest property in Finland after the State, or 661,000 hectares.

There are many areas of old growth forest like this one that environmental organizations believe should be protected for their biodiversity but are instead exploited by the logging industry. Liimatainen, forest campaigner at Greenpeace Finland, has been advocating for stronger environmental protection policies for years. “The forestry industry is not sustainable,” he argues.

“The Constitution establishes everyone’s responsibility to defend ecological values. But the forestry law and other legislation are weak and prevent the protection of this type of forest. That is why there is a biodiversity crisis. Everyone knows there are very few protected areas in Finland.”

The management, conservation, and enhancement of forest ecosystems are crucial to promoting biodiversity and sustainable resource management. The concern of environmental organizations for the environmental sustainability of the Nordic country coexists with the indifference of a large part of society. But, also, with the pride that the forestry industry arouses in the country that, after World War II, saw in its vast territory filled with pines, firs, and birches a way to its economic recovery.

These areas of boreal forest, which are part of the green crown that surrounds the Arctic, cover 75% of the country’s territory, equivalent to 22.5 million hectares. Of these, 90% are used for the forestry industry, mainly to produce pulp.

Liimatainen returns for the second time in a few days to this forest. This time, he arrives with specific topographic maps and printed photos he took with a drone. The clearing is still marked by the truck tires, and the immense stumps help understand the size of the felled forest. “The forestry industry has a lot of power over the government and is a very strong lobby against new European Union regulations that protect old growth forests,” he says.

In the same vein, Juha Aromaa, Deputy Program Director at Greenpeace, points out that “the three big forestry companies have very strong political power when it comes to forest protection in Finland. The industry uses every political opportunity to secure as much raw material as possible, seeking state subsidies, tax reductions, and favourable labour conditions.”

“The forestry industry has a lot of power over the government and is a very strong lobby against new European Union regulations that protect old growth forests.”

Matti Liimatainen, forest campaigner, Greenpeace

The three companies Aromaa refers to are Metsä Group, Stora Enso, and UPM, with a combined sales volume of 25.966 billion euros in 2023, more than a third of Uruguay’s GDP.

Their interests are protected by the Finnish Forest Industries Federation (Metsäteollisuus ry). It is precisely this influence group that the expert from the Ministry of the Environment, Olli Ojala, focuses on. He considers that “the forestry companies are trying to take steps towards sustainability because they understand the risk to their reputation. But then there are the organizations that represent them. Some are ultra-conservative and basically try to maintain the industry’s status quo. They have all the tactics of pressure groups, and they use them.”

Aromaa highlights a crucial aspect regarding the increase in global demand for pulp. Although digitalization and the decrease in newspaper, magazine, and book reading led to a reduction in this market, the rise of e-commerce and the proliferation of home deliveries compensated for this trend.

“To order from Amazon or Alibaba, you need forests, whether they are plantations in Uruguay or natural forests in the Nordic regions. The Finnish forestry industry exports more than 90% of its production, half to the European Union,” Aromaa notes.

Kati Kaskeala, Vice President of Stakeholder Relations at UPM, assures that the pulp industry is indeed sustainable in Finland and emphasizes that the responsibility for forest management does not only lie with the forestry companies or the government.

Regarding the company’s expansion to other places, she speaks of the growing global demand for pulp, saying that “the Finnish model does not have enough wood to produce more pulp sustainably, which is why we have operations in Uruguay, as well as other companies in other places.”

The intermittence of young forests and extensive clear-cut areas defines the constant landscape on the way back from Ruotsinpyhtää to Helsinki. To untrained eyes, it is almost impossible to distinguish between the industrializable forest and the old growth one.

Old growth forests, which represent only 3% of the country’s forest area, become increasingly small oases for rich ecosystems.

In Finland, unlike other countries, artificial, geometrically harmonious forests, or non-native trees are not allowed. Once an area has been cut down, it is replanted with the same species, destined for future industrial use, in a constant cycle that lasts about 70 years and due to its short term, it is difficult for complex biological communities to develop. Old growth forests, which represent only 3% of the country’s forest area, become increasingly small oases for rich ecosystems.

Not only does the deep-rooted forestry industry in Finnish idiosyncrasy dilute the debate around its environmental impact, but also 60% of the forests are owned by small families; more than six hundred thousand people for whom leasing to companies is a very valuable economic asset.

“Felling a few hectares of forest provides extra money to, for example, change cars or renovate a house. For many, protecting forests is perceived as taking away their only economic asset,” emphasizes Ojala.

III.

Around Centenario, there is a theatrical pile of clouds. Only a few fallen weeds and branches dripping with water can be seen. Today, the City Night is just a large sign with red letters and the white silhouettes of two girls in sexual positions. The house is a neglected warehouse with a dirty entrance.

The venue was closed in 2023 for cases of violence against women, suspicions of human trafficking, and sexual exploitation, but the market always finds a way to satisfy demand: less than two kilometres away, on the road leading to UPM 2, behind a dilapidated service station, is Divas Hoott, a black cube where daylight never reaches and where the plant workers often have fun.

It was 2010 when Grace González, tired of the rough and fast-paced life in Montevideo, arrived in Paso de los Toros. She and her husband spent several years exploring different places to relocate and offer a better quality of life for their daughters. It was in this small city that they imagined safety and tranquillity around a beautiful house by the Río Negro.

She would soon find out she was wrong.

In mid-2023, after an investment of US$3.47 billion, UPM 2 was inaugurated right in front of Grace’s house. Since then, the first and last thing Grace sees every day is that industrial mastodon, with its monumental and toxic smoke plumes that stain the roofs of her house when it rains and emits a constant stench of boiled cabbage.

The first and last thing Grace sees every day is that industrial mastodon, with its monumental and toxic smoke plumes that stain the roofs of her house when it rains and emits a constant stench of boiled cabbage.

Grace lives in a rural area with dirt roads and dense vegetation north of Paso de los Toros and the neighbourhood reaches a riverbank and ends with a five-star hotel called Midland, where a single room costs US$200 per night. The dense fog passes calmly over the modern building. The pool and a small water amusement park remain closed.

It is a dark and rainy day, and the plant is not visible. “A happy day for this interview” says Grace. Blond men, white as snow, sitting with their computers in the hotel rooms. The woman in charge of the reception assures that six out of ten guests are Finnish.

“UPM is there every day, and just today it is not. I could outline the shape of that animal. I know it by heart,” notes Grace as she looks for a video on her phone of a barbecue at the end of last summer. On the grill, sausages, and pieces of meat. On the table; drinks, salads, and desserts. Family joy. In the background, the perpetual panting of UPM.

“Well, welcome to Little Helsinki,” says Grace as she drives through the Finnish neighbourhood of Paso de los Toros. The streets are numbered rather than named. There are four houses per block that, by Latin American housing standards, could pass as aspiring palaces. They have underfloor heating, an expensive heating system that goes through the floor and walls, and widely used in the coldest places on the planet.

An old man crosses a street, not feeling observed: he goes slowly, making hesitant steps. Two Rapunzel-like girls ride their bicycles with a serenity that perfects the adjacent silence. The neighbourhood is full of security cameras, and although it is freely accessible, at any moment a guard could come and question the visit.

“If you go to the neighbourhoods UPM built for the workers, you will realize that on a similar land taken by one of these houses, which are for the corporate elite, they have squeezed in ten,” Grace says, adding that “those are not even inhabited anymore; they are abandoned. That was during the boom: they promised jobs, economic activation, and development. I always knew it was a big scam. I remember many neighbors started businesses and went bankrupt, just as many people from other parts of the country came looking for a better life.”

“Have you seen the movie, The Pope’s Toilet? Well, that is what happened. It is no coincidence the movie is Uruguayan. We are a people who live on expectations. What I have in front of my house is not just a company but an entire country. Any day now, I will wake up and see the flag of Finland,” says Grace as she finishes a cigarette and rolls down the car windows.

IV.

Heikki Härkönen rows vigorously for the hundred meters that separate the meeting point in Puumala from the island of Rokansaari, in Lake Saimaa, southeast of Finland. This lake is the largest in the country, the fourth largest in Europe, and an important source of fresh water for the continent.

Under the unusual heat of late May, Härkönen walks for nearly an hour until he stops at a point in the north of this “paradise island.” A perfect straight line separates the forest from a clearing logged in 2022 by UPM, a 14.6-hectare patch in the middle of the lake.

“This logging affected the biodiversity of the area. The forest is growing, but the bare area makes it impossible for many species to settle.” The activist is the local representative of Suomen Luonnonsuojeluliitto, Finland’s oldest nature protection organization, active since 1938.

“This logging affected the biodiversity of the area. The forest is growing, but the bare area makes it impossible for many species to settle.”

Heikki Härkönen, activist.

“This area is protected under the Natura 2000 framework, where some actions, including logging, are allowed. What UPM did is legal; the company is acting according to the law. The problem is that we have a rather deficient forestry law in Finland that needs to be reviewed,” he explains.

And here, the environmental authority had granted the permit for the logging. However, what was supposed to be a “careful logging” ended up being a “clear-felling,” according to Greenpeace.

The island has significant recreational value with trees over 100 years old. In 2023, the company planned similar logging in another part of the island, which provoked opposition from the population and civil society organizations demanding that the activity not be carried out, arguing that some of these areas have a high biodiversity value.

The petition was signed by more than 20,000 people and delivered to UPM. Suomen Luonnonsuojeluliitto appealed to the court, and the company halted the project.

On 25 June 2024, the Administrative Court decided that the company could continue logging in 28 of the 30 planned hectares and returned the case to the Centre for Economic Development, Transport, and the Environment, which had originally granted the permit.

“We are not satisfied with the decision. We have decided to appeal to the Supreme Administrative Court,” Härkönen emphasizes.

“Part of the island is owned by UPM. And although not all the forests there have high conservation value, it is an unspoiled landscape famous for its natural beauty. Transporting heavy machinery to log through the water does not make sense. What happens in Finland is that the entire forestry industry believes it can go anywhere if there is a tree,” says forest campaigner Liimatainen.

In this context, the public debate in the Nordic country regarding the forestry industry focuses on the protection and logging of forests at the local level. Finland is committed to the European Union’s Biodiversity Strategy, which requires the protection of all old-growth and natural forests. However, the definition of ‘old-growth forest’ depends on the states.

Therefore, there is the possibility that economic interests will prevail in biodiversity protection decisions. From Greenpeace offices, Aromaa highlights that “the Finnish definition of old-growth forests certainly will not be scientific. It will be entirely political.”

What happens in Finland is that the entire forestry industry believes it can go anywhere if there is a tree.

Matti Liimatainen, forest campaigner, Greenpeace.

Timber industry towns used to be said to smell of rotten eggs and money. Not in Lappeenranta. The first thing that alerts visitors to the presence of the factory is an enormous chimney towering over a colossal industrial area.

Thousands of logs rest in the lake’s waters, waiting for their turn while hoses and transport machinery never stop functioning. The factory’s pulse does not dictate the rhythm of Lappeenranta. Its citizens coexist with informational brochures that extol the virtues of pulp and the regular arrival of the puutavarajunat, a train of long, open wagons extending over a thousand meters, loaded with tons of wood.

Meanwhile, in downtown Helsinki, near the main railway station, a rainbow-colored banner with the slogan “diversity is natural” hangs from UPM’s headquarters, whose entrance is guarded by the Griffin, a mythological creature half-eagle, half-lion that, according to legend, guards the green gold that the forests harbour.

The Finnish definition of old-growth forests certainly will not be scientific. It will be entirely political.

Juha Aromaa, Deputy Program Director at Greenpeace

“We do not log natural forests. We are in constant conversation with environmental organizations, and when they have informed us about some biodiverse areas, we have decided not to log there. The problem is that there is no clear and established definition in the law of what old-growth forests are,” says Kati Kaskeala, adding that “currently, there are some grey areas because we do not yet have clarity in the political decision-making process.”

The Finnish government defines old-growth forests very strictly, so very few fall into this category. For environmental organisations, there was hope that this definition would slow down the impoverishment of forest nature in the south of the country, but after the announcement, the impact on forest owners and forestry companies will be minimal.

In the city centre stands the Finnish Parliament, a monumental building in classical style with Corinthian columns housing one of the most conservative governments in the country’s history. Until April 2, 2023, the center-left coalition governed the chamber. Maria Ohisalo, from the Green League, was Minister of the Environment and Climate Change between 2022 and 2023.

She explains that “most of the environmental and climate legislation comes from the European Union. As for Finnish legislation, we used to have a regulation that stipulated that trees had to grow more before being cut. Today, that has changed, causing a decrease in carbon sinks. The level of biodiversity in our forests has declined, and we know that approximately one in nine species is at risk in this country.”

Ohisalo, who has been a member of the European Parliament since the June 9 elections, also mentions the lobby of actors influencing political decisions, both in Finland and the European Union. “In the last five years, the European Commission has finally started giving us legislation that is useful and necessary at this time.” For her, the forestry industry is not doing everything it can and therefore “we should be thinking about other ways to produce.”

“There was a time in history when the Finnish forestry industry had to go outside its borders to find raw material. Finland has always been a cold country where wood does not grow so fast, so for several decades, there has been a trend to produce pulp in more tropical countries and then take it to other countries like China,” says Teivo Teivanen, a professor of world politics at the University of Helsinki.

The researcher asserts that the country’s investment agreement with companies does not benefit the country economically, but it does give it the reputation as a country open for foreign investment. “Uruguay has always seen itself as inferior, as a small country among great powers like Argentina and Brazil,” he sentences.

UPM entered Uruguay in the 1990s. From its headquarters in Helsinki, Kaskeala explains that the Latin American country’s forestry law signed in 1987 established priority forestry lands, indicating areas where eucalyptus or pine trees could be planted.

“In that sense, it was the ideal country with a clear framework established by the local government to bring this industry and a stable operating environment,” says the executive with optimistic gestures, adding that currently, the company’s business reputation indicators in Uruguay are favourable. “According to the latest 2023 survey carried out by an external entity, around 80% of Uruguayans have a neutral or positive opinion of UPM.”

V.

In Lion d’Or, an old confectionery in Montevideo, journalist and writer Víctor L. Bacchetta sits down and, before unleashing his investigative arsenal, orders a cortado coffee to fend off the afternoon cold.

Outside, on the Avenida 18 de Julio, the country’s most important avenue, the autumn leaves rustle among the diligent footsteps of the passers-by. Víctor is 81 years old, but his attitude is that of an 18-year-old activist. From his backpack, he takes out three books: La entrega, el proyecto Uruguay-UPM (2019) [The handover, the Uruguay-UPM project], that he edited, and El fraude de la celulosa (2008) [The cellulose fraud] and El pacto colonial (2021) [The colonial pact], that he wrote.

We are talking about neocolonialism, and one says it and emphasizes it, and no one takes it seriously.

Víctor L. Bacchetta, journalist.

Although the titles of the books are quite eloquent, Víctor has one clear and concise point to emphasize: “Uruguay gains nothing from UPM and, on the contrary, gives away many things; Aside from the dreadful environmental problem that a company of this magnitude implies anywhere in the world, what is at stake here is sovereignty. We are talking about neocolonialism, and one says it and emphasizes it, and no one takes it seriously; they think one is against national progress or, in the worst case, that one is crazy.”

Illustrating Victor’s point, activists Mariana Barrán, a 47-year-old social worker, and Marcelo Fagúndez, a 49-year-old independent driver, not only suffer the same discredit, but are actually demonized by the community of Guichón, a town of five thousand inhabitants located west of Paysandú, the fourth largest city of Uruguay.

“Criticism is paid with discrimination,” says Marcelo in his living room while he fills the stove with firewood to fend off the harsh polar wave. Mariana prepares a mate and passes it around while recounting the story of the Guichón Collective for Natural Goods, a community initiative that, at its peak, was joined by 30 families, but today it only has 15 active members.

“We organized ourselves in 2011 with the aim of avoiding the ecocide we are already experiencing,” Marcelo adds.

“People do not seem to care if they are deprived of water, if it gets polluted, or if the lands and the Pampas landscape are invaded with non-native species like eucalyptus. The only mystery that all these surrounding forests hold is that of infertility,” says Mariana, adding that “those eucalyptus monocultures and the chemicals used to make them grow faster ruin the soil. By the time they leave, in fifty years, which is the time the government signed for, this land will be good for nothing when its main characteristic was its richness.”

In Guichón, there is silence because there is money. Many locals live, in one way or another, with the wealth provided by UPM. Outside the town, the company has, next to the Santana stream, a eucalyptus nursery where around 200 people work.

In Guichón, there is silence because there is money.

According to Marcelo, since 2018, four years after the nursery was inaugurated, the consumption of water from the Santana stream has been banned due to contamination, and the town had to be assisted with water trucks, a phenomenon never seen before, compounded by the strange appearance of algal blooms that crept into showers, causing foul smells and skin allergies.

“People only react when they are directly affected,” explains Mariana, noting that “in 2015, the water of the stream turned reddish and gave off an acidic smell. We warned, but no one listened. They said we were jealous because we did not get jobs in the nursery. Weeks later, there was a terrible fish die-off. And there is more, ten years ago, it was common to see herons, hares, and even otters; today, we do not know where they are, or if they are still there at all.”

To reach the nursery, one must leave Uruguay and enter Finland. The change in landscape is as abrupt as that which separates the two countries, united by UPM: from the persistent and bright South American pampas to the opacity of Nordic forests.

To reach the nursery, one must leave Uruguay and enter Finland. The change in landscape is as abrupt as that which separates the two countries, united by UPM.

At the edge of one of the many eucalyptus plantations that surround Guichón, a group of cows stand still, rigid, contemplating what used to be productive ranches. Inside the forest, the sound of chainsaws.

VI.

Metsä’ means forest in Finnish. According to Marianella’s work, one could infer that Uruguayan forests are furious, but which forests? Uruguay is a country of prairies. Long stretches of generous land that, at one point, along with Argentina, were known as the world’s pantry. Perhaps the Finnish forests in Uruguay are the ones that are furious, planted 12,732 kilometres away from home.

Below: UPM’s Santana Nursery inaugurated in 2012 by then President of the Republic Pepe Mujica, Guichón, Paysandú, Uruguay. Photos: Dahian Cifuentes

The company believes it is doing Uruguay a favour. One of the major global discourses on environmental threats focuses on deforestation, that is, the indiscriminate felling of trees. What UPM does is precisely the opposite: it forests. It plants trees, an action the multinational staunchly defends under a questionable and spurious commitment to the environment. A pine tree in Finland (eucalyptus is prohibited there as it is not a native species) takes up to 12 years to mature. In Uruguay, eucalyptus (also a non-native species) grows in six.

The Uruguayan soil is rich, yes, but to achieve such growth, it needs extra help: UPM calls them agrochemicals; Mariana calls them ‘agrotoxins.’ “There, they can’t plant and harvest, so they came here,” Marcelo points out. Today, Uruguay has 1.3 million hectares planted with eucalyptus, almost 8% of the national territory.

It is an impeccably clear and peaceful morning. The plain, in the distance, looks like a gleaming watercolour painting. The eucalyptus trees hold many things here; they prevent the rampant unemployment suffered by the farmers of the nearby towns, but people are exhausted, at the limit of their physical and mental strength.

One of the major global discourses on environmental threats focuses on deforestation, that is, the indiscriminate felling of trees. What UPM does is precisely the opposite: it forests.

First, trees up to twenty meters tall, then long spaces completely ravaged, and finally trunks grouped like giant piles of firewood. What does not change is the blue fire of the loggers that smolders everywhere. Although it is freezing and there is frost on the grass, the workers arrive punctually at the UPM nursery. A new workday begins.

Piñera is asleep, but not dead. The town has a little over one hundred and fifty inhabitants and is a 20-minute drive from Guichón. The clouds and fog cover the tops of the eucalyptus trees. Someone carries straw on their back. The farmers are silent, besieged by scarcity. The fire, in their homes, is the priority. It warms the air that, at three or four degrees less, could turn to ice in the blink of an eye.

It is Saturday. On the TV in the living room, there is a soccer match, and further inside, in the privacy of a room, her two children play at being superheroes. Liliana, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, wears thick glasses, but even so, she cannot hide her sadness.

At some point in the conversation, she will say that she is tired, but then she will return to her soft voice and distant gaze. She joined the nursery in 2014, and since then, every working day, a bus picks her up at seven in the morning and drops her off at six in the evening. Every day, Liliana handles thousands of baby eucalyptus trees: she selects them, prunes them, stimulates them, and transplants them into trays that go to the greenhouses.

Liliana improvises the movements of her work. They are as monotonous as the afternoon occurring outside, and her mood is as stiff as the tendinitis that quietly develops in her hands. “I hate summer; inside the nursery, the temperature exceeds forty degrees, and you have to keep going, suffocated, as if you were in hell,” she says, with a shadowed face.

Julio Silva is Liliana’s colleague and has three years left until retirement. Since 2013, he has been a member of the Union of Wood Industry Workers and Related Professions (SOIMA). His salary is the minimum in Uruguay (22,000 Uruguayan pesos, equivalent to about 500 euros), but he does not receive it in full due to legal deductions. Just for the rent of the house where he lives with two of his children, his wife and eight cats, he spends half of his salary and the rest is barely enough to survive.

Julio starts the conversation by saying that his work is not easy, and that boredom has already made him forget when he first felt that bad mood would be his destiny – this is a colloquial expression that implies the fact that going to work or directly to work has brought Julio a constant bad mood, bad feeling, bitterness.

“At the nursery, I am harassed for being unionized. I do not stay silent; if I see an injustice, I report it. They make my life impossible. They forbid my colleagues from talking to me, they say things behind my back, like I am a bad influence, but I am already seasoned. I am going for retirement. I have never been in jail, but working at the nursery must be very similar. The boss has told me several times not to get involved in what does not concern me, but I am an Artiguist at heart and I always reply: ‘With the truth, I neither offend nor fear’,” says Julio.

“These companies use Uruguay’s laws as toilet paper. They know we need work to avoid starvation. But well, the first thing I am going to do when I retire is to fulfil my lifelong dream: to go see Peñarol play,” Julio concludes, sitting in his backyard with his soul mate, surrounded by their feline offspring.

VII.

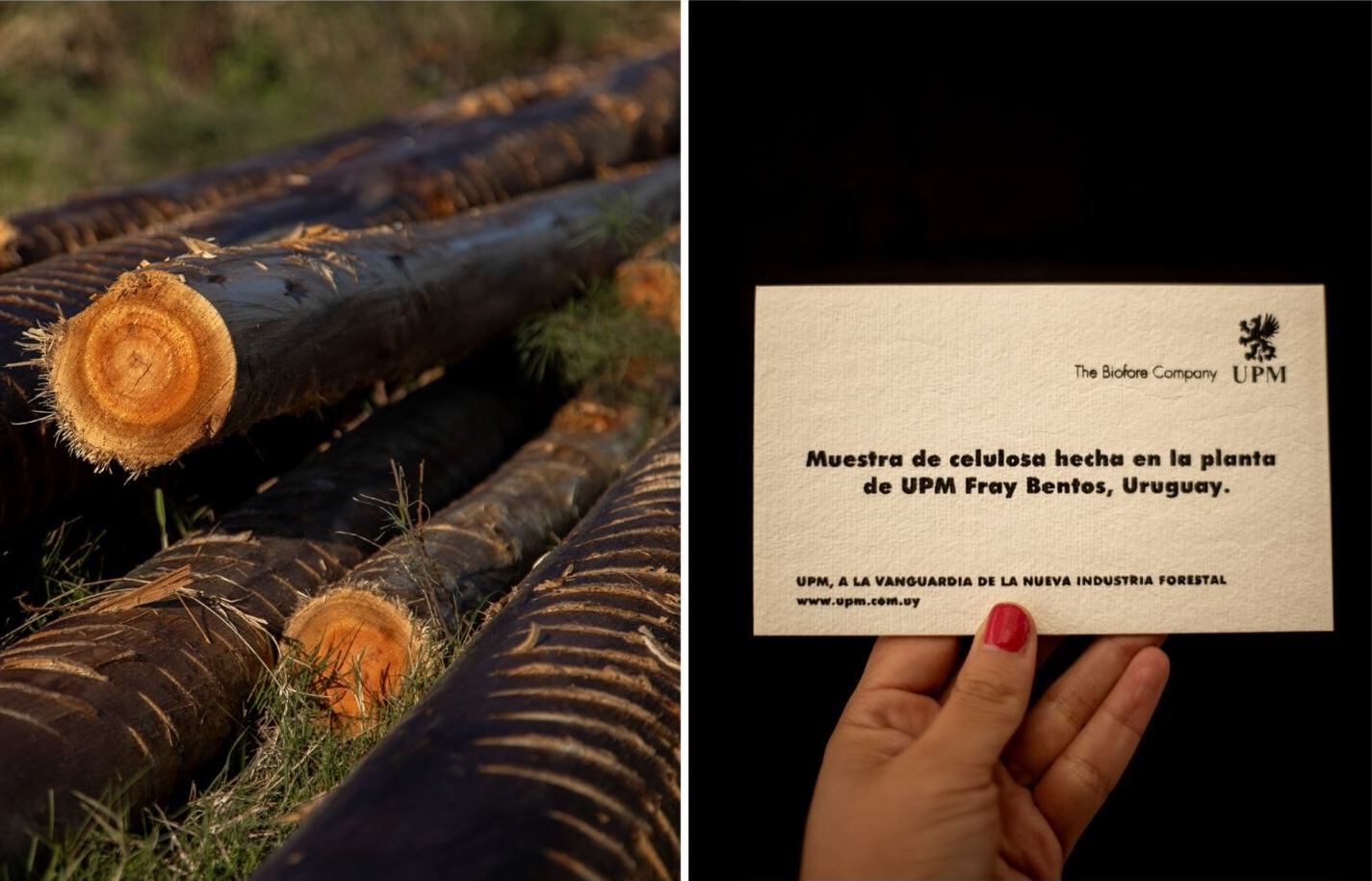

Back in Guinchón, Mariana holds a white cloth bag with the UPM logo. Inside, there is a green retractable pen with the inscription ‘UPM Biofore – Beyond fossils’ and a white folder with a brochure and a magazine. The brochure is titled: “How do we make pulp?” It contains the ABC of production, from explaining what pulp is, what it is used for, where it comes from, and how it is extracted, to the company’s commitments to the environment to keep rivers and air clean.

The magazine is called “The Amazing World of Afforestation. Discover it with Cami and Facu..” On the cover, a teenager and a child walk through a forest accompanied by a duck. Finally, the kit comes with a small sample of pulp made at UPM’s Fray Bentos plant. This bag has been given to thousands of Uruguayan children and teenagers along with chocolate milk and a cookie. “Pure nonsense, perfect for convincing and glossing over reality,” says Mariana.

UPM’s propaganda goes much further than the children’s fable and the cookie. Almost 400 kilometres south of Guichón, in Punta Espinillo, on the outskirts of Montevideo, Daniel Pena makes a fire.

He inherited the land from his parents and is building a house with his own hands. He lives with a dog, a cat, and the lullaby of nature. The most beautiful thing he has, he says, is the Río de la Plata beach less than three hundred meters away.

Daniel is a sociologist and a professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of the Republic. Just over thirty years old, he is already a reference in environmental research in Uruguay. The fire is ready, the night is bright, but Daniel is drawn into another kind of darkness, reality:

The interference that UPM has in Uruguayan education is extremely serious.

Daniel Pena, Sociologist.

“The interference that UPM has in Uruguayan education is extremely serious. By law, since the contract was signed, the company has been authorized to enter any level of the national education system,” he explains, adding with concern that “this had never happened before with any company, to have permission to basically lecture about what it does and its interests.

Additionally, he says, “the State is required to create educational plans that respond to UPM’s needs. All this through its foundation, which also provides courses in very remote rural areas, for all ages, making people feel grateful and indebted to the company and forget the duties of the State. UPM is shaping people in Uruguay or, better, making them obedient to follow the script that suits them regarding pulp being, for example, the future of the country.”

Children grow up with this information and when they are older, “they will reproduce it, not only because they heard it, read it, memorized it, but because they saw it,” sentences Pena, noting also that “the company has a free hand to educate people in a country that, paradoxically, has stood out for defending education without interference for over a hundred years.”

In a column titled “UPM and Uruguayan Public Education” published in June 2019 by Semanario Brecha, journalist Alma Bolón writes: “The obligations Uruguay takes on in terms of education in ‘the region of influence’ of the Finnish company are evident: Uruguay is forcing itself to organize and finance educational policies that are explicitly imposed by a foreign company to which Uruguay is accountable for. It is obvious that a sovereign state cannot sign an agreement by which it agrees to renounce its own secular republican conception of teaching, in favor of ‘taking into account and applying in good faith the visions of UPM,’ that is, a private company from another state (in this case, a state whose official religion is the Evangelical Lutheran Church) and whose interest in Uruguay is exclusively profit-driven.”

Added to this is the company’s ability to create euphemisms like “we produce the future,” a simple slogan that collapses with two simple words: environmental impact.

It is obvious that a sovereign state cannot sign an agreement by which it agrees to renounce its own secular republican conception of teaching, in favor of ‘taking into account and applying in good faith the visions of UPM.’

Alma Bolón, journalist.

In Rincón del Bonete, a tiny town located on the banks of a massive dam drew attention at the end of 2023 due to a stream off of the Río Negro which, according to a representative from the Ministry of Environment, “was extinguished” due to the spill of a million liters of caustic soda that UPM intentionally released through a clandestine pipe.

The incident took place on August 16, 2023, but was only reported to the public forty days later. A local source who prefers to remain anonymous claims that “more than a month passed and no one, not even the Ministry of Environment, could say anything until UPM basically authorized the release of the news.”

In the meantime, the local source continues, “they cleaned up the field and took advantage of the rains that naturally diluted the chemical spilled into the surrounding watersheds. They then paid a paltry fine of 182,000 dollars, not even a scratch for a company that turns over hundreds of millions of dollars a year. One wonders: Whose country is this?”

According to the Water Observatory in Uruguay, the company not only destroys and attacks the primary resources of use and life like land and water, but also replaces fertile pampas with monocultures, managing a type of future erosion that is already ruining the native biodiversity. What were once livestock and dairy fields are now lands exhausted by eucalyptus with little human presence.

According to Daniel, rural migrations have increased in recent years because there is no work due to lands being leased for up to ten years for forestry: “They dismantle rural social fabrics and push people to the cities in politically correct ways, for the good of the market. In Uruguay, houses of farmers are not set on fire, but they are cornered and economically and ecologically suffocated, and no one can endure that.”

Nevertheless, people who work at the plants receive decent wages (very different from those at the nursery), but at the cost of workdays of up to twelve hours that disrupt family dynamics, increase depression, alcoholism, and, at the same time, drive the emergence of drug addictions like cocaine. UPM uses the discourse of modernizing the countryside, but what is behind it is a voracious agro-industrial logic.

There’s a lack of concrete statistical data, but conclusions are based on testimonies, and the fact that the company itself issued a warning that all these things could increase once the Paso de los Toros plant was inaugurated. In other words, they knew what was coming.

What were once livestock and dairy fields are now lands exhausted by eucalyptus with little human presence.

What they do, explains Daniel, “is extract resources and expel people from the territories. This multinational concentrates wealth because it controls the entire chain, from nurseries to when the pulp leaves the port of Montevideo. UPM damages soil, harms rivers, damages subjectivities, harms people’s health, and destroys social fabrics. They back themselves with international certifications issued by private companies.”

He continues explaining that a former worker told him, for example, that “UPM forced him to hide dead fauna. According to official data from the Ministry of Environment, UPM has 52 fines for violating Uruguay’s environmental regulations: felling native forest, violating land use regulations, mining for roads in restricted areas, spills, industry management violations, and use of agrochemicals prohibited almost everywhere.”

“They claim to capture carbon because they afforest, but they only consider the growth period of their trees, not the moment carbon is released because they devastate native pampas. And the cherry on top: they don’t pay taxes because they are located in free trade zones. This is not sovereignty,” Daniel points out while serving a lentil stew.

Autumn continues to make its way through the north-western Uruguayan countryside. The season is wet and colder than usual. There is dripping water, muddy grasses, and gaseous surfaces everywhere. Uruguay is solitude. The interior has the silence of a tomb that is only interrupted by the wind.

VIII.

In the heart of Helsinki, the iconic Senate Square became the epicentre of the climate march organized by environmental groups on June 2. Thousands of people of all ages flooded the capital’s streets, calling for a more harmonious relationship with the planet.

Without a unified direction, each banner raised amidst the commotion expressed a call to reduce carbon emissions, radically transform production and consumption models, or intensify the protection of endangered species and fragile ecosystems. Along the route to Kansalaistori Square, which connects the Parliament, the Central Library, and UPM offices, a constant cry echoed: ‘Lisää ääntä.’ Louder.

“Finland’s economic dependence on the timber industry, driven by state subsidies and high tax revenues, makes it difficult to convince people that the system which provides us so much well-being is being built at the expense of land, labour, and the environment in Uruguay,” says Janette Kotivirta, who is pursuing a PhD at the University of Helsinki on the impact of the Finnish forestry industry in Uruguay.

This is why she has travelled to the country to establish connections with local organizations and communities.

“There is a growing relationship between social movements here and in Uruguay. The reduction in production must occur simultaneously and in collaboration between the social movement here and elsewhere because we know there is a trend of Northern Global companies to outsource and move to the Global South,” Kotivirta, also an activist with the Climate Debt movement, argues.

“By being connected, we are trying to move towards real environmental justice to ensure that the green transition in the Global North does not become a colonizing project in the Global South,” she sentences.

Kotivirta will return to the land of the pampas and eucalyptus in a few months to continue her project. Her work is supervised by Maria Ehrnström-Fuentes, a researcher whose work has focused for over a decade on analyzing corporate social responsibility policies, particularly concerning various forms of extractivism in the forestry sector in South America.

“We have been educated to be grateful to the forestry sector. Finland’s economy, well-being, and the free education we have had up to university were built with the help of the forestry sector. Therefore, I can sympathize with a Uruguayan society that believes this same wealth will also come to their country,” she states.

Ehrnström-Fuentes speaks of her country as a society that has lost the memory of what the forest meant to its ancestors. “Only in recent years have we started to question biodiversity, ecology, and how we will restore forests affected by the forestry industry in Finland. It is difficult to discuss this in a society where most people live off what the forest once provided.”

While the forest has always played a leading role in Finnish history, in Uruguay it was virtually non-existent. “If a Uruguayan visits a forest in Finland, they will quickly realize that it is not the same as what is in Uruguay, because what there is are monocultures.”

While the forest has always played a leading role in Finnish history, in Uruguay it was virtually non-existent.

Ehrnström knows what she is talking about when she criticizes the forestry industry. She worked in it at the beginning of her career. It was 2004, she was living in Latin America, thinking it was an environmentally friendly sector, until she visited communities in Chile and Uruguay.

“I understood that conflicts serve to show us that the model on which we are building our wealth, our way of living in urban centres, has a high cost in the destruction of land, which is invisible to those who live off the sector,” she says.

With UPN’s opening of its second plant in Uruguay, in April 2023, on the banks of the Río Negro, near Paso de los Toros, Uruguay welcomed its third pulp plant in the country, alongside the factory of the Nordic company Stora Enso and its Chilean subsidiary Arauco.

“We need to abandon this model of mega pulp plants and industrial tree plantations that use a lot of water, poison and degrade the soil, causing social and climate problems,” emphasizes Markus Kröger, a researcher on global development and forestry extractivism in Latin America, adding that “in Uruguay, there is talk of expansion plans of a fourth Japanese factory. At this time of climate and ecological crisis, we cannot waste our waters and soils for this type of unnecessary production.”

Following the opening of UPM’s second factory, activist Kotivirta participated in a coordinated action between social movements from both countries, including blockading roads to the Kuusankoski pulp factory in Finland and the Pueblo Centenario in Uruguay.

According to her, “to truly understand the impact of this company, we need to understand the historical context and realize that it is not about assessing the individual actions of a company to determine if something is colonialism or not. It is about understanding global exploitation structures. This company is simply taking advantage of existing conditions, where the exploitation of natural resources and labour from the Global South is very beneficial to them. Labelling UPM as a colonial company distracts us from the main issue: exploitation structures exist and will continue to exist.”

Local, national, and international resistance can prevent the expansion of investments, as Kröger argues. According to the researcher, companies usually choose areas with less resistance, as has been the case in Uruguay: “There are several cases where the expansion of eucalyptus plantations has been reduced due to similar resistances. This includes occupations, politically organized campaigns, social movements, and protests. Interaction with other organizations and movements, as well as influencing state regulations, can make a difference.”

IX.

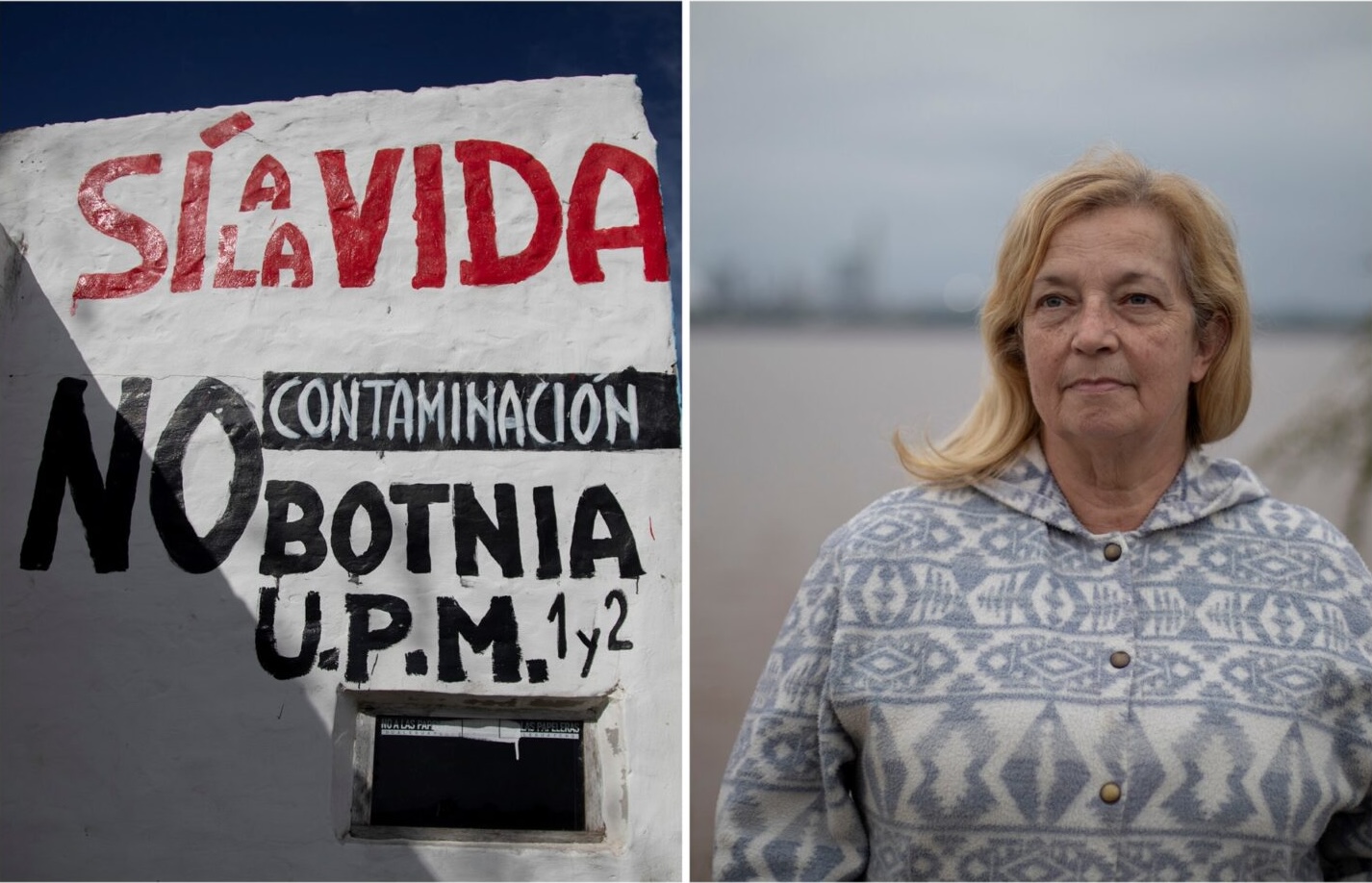

In Fray Bentos, along the border with Argentina, the Uruguay River winds its deep waters with discouragement. May is a time of year that invites introspection. Drizzles begin, it gets dark, and hoarseness takes hold of the bodies. The sky ends abruptly, and with the night comes loneliness. People walk silently. UPM shines like a city that knows no dream. A chimera that promised to return the city to the podium of national industry.

The city’s streets carry an air of industrial melancholy. At times, it smells of rotten eggs, but in the blink of an eye, a gust of wind carries the smell away. The first company to arrive, dedicated to the production of pulp, was Metsä-Botnia in 2007, but it fell under UPM’s control in 2009.

Robert Urgoite, 39 years old, is a social psychologist. He chooses the National Basketball Club as a place to talk. When asked what the paper industry has brought to Fray Bentos, Robert touches his chin, presses his lips together, and opens his eyes with emotion.

“Incredible but true,” he explains, “disappointment because many people signed up for the supposed economic reactivation and went bankrupt; unemployment because they never fulfilled the promise of jobs; prostitution due to the influx of foreign male workers; drug trafficking because the workdays were long just like the nights in the city; pollution for obvious reasons. Let’s sum it up as sadness.”

He adds that “this was all back when there was a fuss with the Argentinians, who were deeply suspicious of the multinational and not only protested but also took the matter to the International Court of The Hague, which eventually ruled in favour of the plant’s operation. Today, it is a factory that exists and does not exist. No one pays much attention to it. They did so much advertising that people either got fed up, believed the story, or simply forgot. I remember a commercial from that time: a Uruguayan journalist went to Finland and drank a glass of water from a lake in front of a paper mill to prove that pollution claims were false. They did anything to convince, but well, we already know that those who pollute the most are often the ones with the loudest environmentalist rhetoric.”

María Forte, 64 years old, an ecofeminist, graduated in 2010 from the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of the Republic, argues what she considers to be the underlying issue: “The plant is a branch of Finland in Fray Bentos.” María has her hair dyed blonde and as she speaks, she switches hands between her mate and two crochet needles. “I don’t keep quiet about anything,” she says, beginning to describe the same social discrimination that Mariana and Marcelo face in Guichón.

María’s house is on a corner, and although it is not close to the river, it receives all the wind coming from the basin. “That white dust on the car is not dirt, it’s ammonia coming from UPM’s chimney. Did you smell the foul odour last night and this morning? It does not take much effort to know where it comes from,” she comments.

For María, not everything is a disaster, as long as people can become aware and organize themselves. She herself leads a group of citizens from Fray Bentos who stay alert to everything related to UPM. “The river was a crucial source of food and now you cannot eat anything from it. Since 2018 there has been a decree that prohibits catching fish for study.”

The river was a crucial source of food and now you cannot eat anything from it. Since 2018 there has been a decree that prohibits catching fish for study.

María Forte, ecofeminist.

“I ask: where are they going to dispose of all their waste if not in the river? They take care because they know and have a lot of power,” María continues, while on a small point on the coast of the Uruguay River, opposite the UPM plant, she points out formations of bright green algae, which she believes to be contamination already mutated with the river.

“And where do you think all the energy UPM uses comes from? Asks María, just to answer that “they produce it themselves with our water, and because they produce so much, the surplus is bought by the Uruguayan government, which is obliged to do so by contract. It is unbelievable: they come from abroad, use everything that is here, and then sell us the leftovers of what they extract and take away.”

“They chose Uruguay because no one controls them, and well, there is not as much technology available here, to measure things like the pollution caused by ‘agrotoxins’ in people’s blood. They have sold out the country, and the state is complicit. Environmental wealth, institutional weakness, and free trade zones throughout the country brought them here. An environmental crime should be declared,” María details, while showing the Finnish neighbourhood of Fray Bentos.

The void is deep and ruthless. The few people who wander the Fray Bentos night stumble instead of walking. There is drizzle. No sound comes from the Uruguay River; it continues its course peacefully and silently.

“They are killing the river, but its consequences will only be visible in 30 or 40 years, when it will be too late to do much. We must resist and create dialogues to counteract this violation of our own laws, which give companies what they ask for and also order. In other words, the colonization of the country,” says María, who, during her breaks, is one of those people who usually knows how to say the right thing. She resists so as not to collapse in the face of the new reality: yesterday they colonized with armies, today they do it with companies.

Yesterday they colonized with armies, today they do it with companies.

In any case, says Víctor L. Bacchetta, “we must be grateful that in Uruguay we can still talk about this. What we do and how we do it cannot be done in the rest of Latin America. In Brazil, Colombia, or Mexico, we would already be dead. A company that earns an average of one and a half million dollars a day would have already caused us to suffer a mysterious accident.

X.

“Victor Bacchetta and I have the best of relationships, as do we with the communities where we work,” says Matías Martínez, with a smile bigger than Luis Suárez’s when he scores a goal “We remain open to everything in Uruguay, dialogue and support are a priority.”

Matías is the Senior Communications Manager for UPM Uruguay and speaks surrounded by a wallpaper showing a sparsely populated bookshelf and two lush emerald, green plants.

He adds that “we are specialized in being the top of the class in not neglecting anything. We are committed to improving and doing everything in the best possible way, meeting all environmental requirements and regulations, having interesting social projects, and being a source of employment. However, there are things we cannot control, such as drug use or prostitution, which, for example, has existed for centuries.”

Now, while on June 2nd civil society and environmental organizations were marching in Helsinki, in Uruguay, Revista Verde, a publication specializing in land and agricultural business, revealed a piece of news: “Japanese company Oji Holding Corporation, one of the leaders in the global pulp and paper industry (with forested lands in countries such as Brazil, Australia, Canada, China, New Zealand, Indonesia, Vietnam, among others), shook the land market with the purchase of 41,289 hectares for US$287,598,326 in the departments of Tacuarembó and Rivera.”

The news, almost unnoticed, would have had a bit more eloquence in some obituary section under a title like: “A New Pulp Mill is Coming.”

On March 5, 2024, Marianella left the National Theatre of Helsinki. Moments before, she had been applauded for the premiere of her work. Several people approached to congratulate her, and in an almost impossible physical expression in Finland, a film director energetically hugged her and whispered in her ear: “I am very ashamed to be Finnish.” The fourth wall had been broken: far from a mere enchantment, the Finnish audience was already merged with the Uruguayan scenes.

A day before the closing of this investigation, Raúl Viñas, member of the Movement for a Sustainable Uruguay, was contacted via WhatsApp to corroborate an information received from Centenario stating an alleged leakage of liquid waste in a local stream: “Yes, there was another spill and, as happened the previous time, the Ministry of Environment hid the information. The spill was on June 18, but only a month later, until July 19 it made a pronouncement. We are in a bad way with this. “We spoke when we could” was what Uruguay’s Environment Minister Robert Bouvier said about the previous spill. What they say is that it is not their mission to inform, to which we answer: “Then who informs? Could it be that UPM is the one that tells the government whether it can speak, what to say, how and when?

*The research and writing of this article were supported by Journalismfund Europe