Confronting War Debris to Protect Europe’s Seas

Europe’s seafloor holds millions of tonnes of unexploded munitions, threatening marine life, offshore energy expansion and coastal communities.

Europe’s seafloor holds millions of tonnes of unexploded munitions, threatening marine life, offshore energy expansion and coastal communities.

Professor Jens Greinert of GEOMAR explains where these weapons came from, how they affect today’s blue economy and what new technologies may finally make industrial-scale cleanup possible.

To begin, could you explain how all this ammunition originally entered the sea?

There are three main pathways. The first is wartime activity. Whenever ships fire artillery, aircraft drop bombs or navies deploy sea mines, munitions inevitably end up in the water. There are also cases where ships carrying ammunition are hit and sink with their cargo. This is still happening today in the Black Sea where war activity continues.

The second pathway is modern military training. Many shooting ranges still fire ammunition into coastal waters during testing. This is ongoing and adds new material to what was already there.

The third, and from our perspective the most important, is post war dumping. After World War II, the Allies wanted Germany demilitarised as fast as possible. Everything had to go, tanks, weapons and enormous amounts of unfused ammunition. The decision was to dump it offshore. Whether it was wise or not is no longer the question; the material is there and it must be dealt with. Chemical weapons were also dumped in places like the Bornholm Basin. These three processes together created the problem we face today.

With the ongoing war in Ukraine, do you think this will become another long term munitions crisis?

Yes, without doubt. Ukraine will face the consequences of unexploded ordnance for at least 30 to 50 years. Clearing landmines alone is a generational effort. We have seen the same in Kosovo and in several Asian countries where people still deal with munitions from conflicts 40 or 50 years old. Ukraine will be similar. Cluster munitions, sea mines and explosives displaced by the major dam break have all entered the environment. The situation in the marine zone is only one part of a much larger clearance challenge ahead.

What impact do old munitions have on tourism, fisheries and offshore wind today?

The offshore wind industry learned quickly that old munitions complicate development. Ten to fifteen years ago, when the first big offshore projects began, developers realised that before you hammer a pylon into the seafloor or lay a cable, you must clear the area. Offshore energy has a financial structure and a business model, so clearance costs can be absorbed. Ultimately, the consumer pays through the electricity price.

Tourism is different. People do not want explosives washing up on beaches. Once the public learns that munitions are on the seafloor, even if they never see them directly, they feel uneasy. In the Baltic region, there are even warnings because amber can be confused with white phosphorus, which burns severely. Tourist boards rarely highlight this, but local communities want the problem addressed.

Fishermen have known about munitions for 80 years. Everyone has hauled grenades or shells in their nets. Their first concern is whether the net survives because repairs cost time and money. They usually throw the ammunition back into the sea. But fishermen also know that TNT and other chemicals enter the ecosystem. We can detect TNT in fish and mussels. Toxicologists say the concentrations are currently low enough to eat seafood safely, but TNT is carcinogenic and mutagenic. The question is what happens in the coming decade. From an environmental perspective, the acceptable concentration is zero.

This is clearly a cross-border issue. How do we convince landlocked countries to support expensive cleanup efforts?

There are three main arguments. First, energy. Offshore wind power does not benefit only coastal states. Electricity feeds into a European grid. Landlocked countries like Serbia or Austria use power generated at sea and benefit from reduced dependence on imported fossil fuels.

Second, solidarity. Europe is built on the idea that countries support each other even if impacts differ. Landlocked countries also have munitions in rivers, lakes and old training grounds. A European mechanism could address both marine and terrestrial clearance.

Third, long term cost. Leaving munitions in place increases environmental and economic risks. Clearing them later becomes more expensive. It is cheaper and safer to act together now.

When an unexploded ordnance is found, who is actually responsible for clearing it?

Responsibility is fragmented and unclear in most countries. Germany is a particularly difficult case because of its federal structure. Within the 12 mile zone the state is responsible. Outside the 12 mile zone the federal government is responsible. But when motorways or pipelines are involved, responsibilities shift again. It becomes extremely confusing.

In most European countries, the military and the Ministry of Transport share responsibility, but even they often have overlapping roles. No country can say clearly that one institution is solely responsible with a defined process. This lack of clarity is exactly why projects like MMinE-SwEEPER exist. Their goal is to map responsibilities, compare national approaches and identify best practices. In Germany the Ministry of Environment has temporarily taken the lead, mainly for environmental reasons, but in the long term the Ministry of Transport is better suited.

How costly is safe disposal of these munitions?

For ad hoc clearance we have reasonably good estimates. Survey work, diving teams and technical equipment can cost around 50,000 to 60,000 euros per day. A three week operation can cost several million euros and might recover a few hundred items.

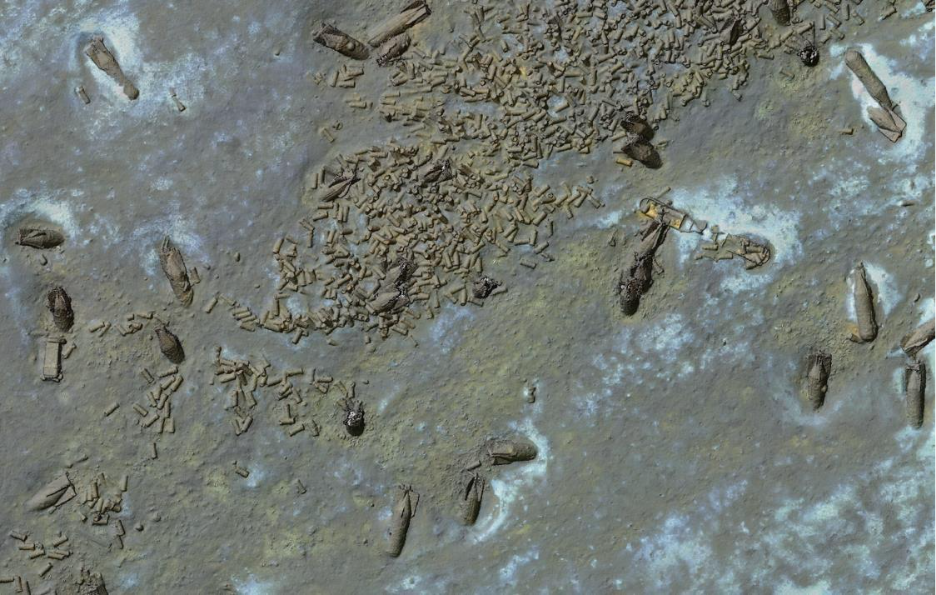

Dump sites are very different. Instead of one shell, you might have piles stretching tens of meters. Divers must literally walk across overlapping munitions, which is neither safe nor scalable.

Germany recently funded trials to gauge cost at a larger scale. Three companies were each given 30 days to clear a specific pile. One company received roughly 5 million euros for a single month of work and successfully removed the entire pile. They relied heavily on divers, which cannot be used to clear hundreds of piles. Clearing 1.6 million tonnes in German waters cannot rely on manual methods. We need industrial systems.

Many EU projects focus on mapping or detection. What makes the CAMMera project different?

CAMMera addresses the missing step, industrial scale recovery and disposal. We already understand where munitions are and what environmental impacts they cause. We are improving detection with autonomous underwater vehicles. But the bottleneck is removal and disassembly.

CAMMera brings several partners together to design the technology needed for large scale work. One partner focuses on lifting very large rocket warheads, some with around one ton of explosives and fragile casings. Another partner, Fugro, specialises in remotely operated systems for raising large objects safely.

SeaTerra is developing automated tools to pick up smaller munitions, such as bombs, grenades or munition boxes, using a remotely crewed surface vessel. The system lowers a tool on a cable, grabs the item, loads it into a basket and transports it automatically.

Finally, DynaSafe will design next generation disassembly lines. Today, most disposal facilities can dismantle one bomb every two days. That is not enough. To process Europe’s legacy of 1.6 million tonnes, we need to handle twenty bombs per day. CAMMera will not build such a plant, but it will design the technical blueprint.

The project also focuses on creating a European business case. The European Parliament wants clarity on costs, governance and funding mechanisms. CAMMera will propose how an EU wide clearance system could work.