Circularity and the Redefinition of Beauty in the Built Environment

A sustainable economy depends on an aesthetic revolution valuing resilience and beautiful imperfection over pristine newness.

Despite the dominance of the “make-take-dispose” culture embedded in our global economy, society has a long history of making do with what we have. In traditional Japanese culture, the necessity of extending an object’s life is elevated through Wabi-Sabi, a philosophy that finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and age, brought to life by the practice of Kintsugi. Literally translated to gold joinery, the practice takes broken pottery and doesn’t just repair the item, it transforms it using a special lacquer mixed with gold dust. By drawing attention to the mend with this precious material, creates beauty out of an apparent imperfection, instead of concealing it: turning something into beautiful because of its flaws instead of despite them.

This mindset, common before the age of mass production, is now a philosophical blueprint for circular design. Historically, objects were built to last: furniture relied on durable, separable joints (dowels or dovetail joints instead of glue) ensuring the components could be repaired or maintained by a local craftsman. Consumers expected objects to last and to be repaired.

Today’s linear take-make-dispose model is a stark contrast to the philosophy of Wabi-Sabi: when something shows signs of age or imperfection, it’s time for it to be replaced with something new, driving a continuous demand for virgin resources. According to the 2024 Global Resource Outlook, an annual report developed by the United Nations Environmental Programme and International Resources Panel, the extraction of the Earth’s natural resources has tripled over the last 50 years.

Linear economy versus planet(ary limits)

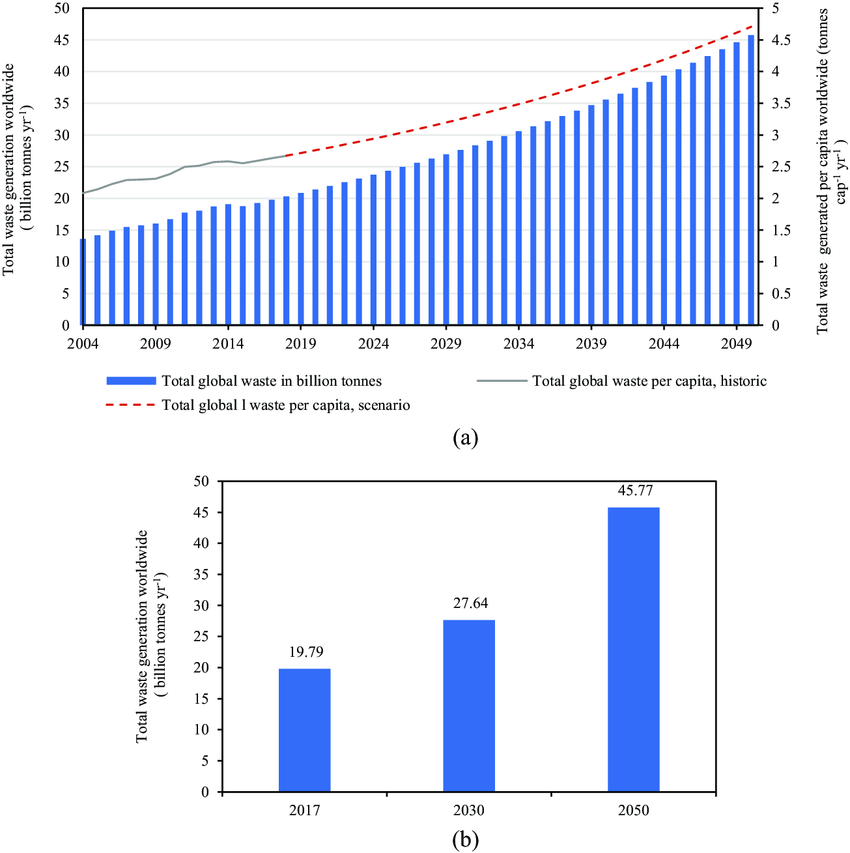

This endless demand for new resources comes with a complementary waste problem. Beyond the sheer tonnage of material waste – which, according to a study published in 2022, could reach up to 49 billion tonnes by 2050 under a business-as-usual scenario – the hidden environmental costs are immense.

In terms of land use, the true scale of the problem is hard to define, with estimates for the total number of landfills worldwide ranging between 10,000-100,000. When it comes to scale, the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island, New York, takes home the dubious honour of being the Guiness World Record holder for the largest refuse tip, covering 12 km2 – the equivalent of over 2,200 American football fields. From there, we need to also consider to the methane emissions, which have become the third largest source of methane emissions globally, according to a 2025 study published in Nature Climate Change, as well as water and soil pollution and the global ocean plastic pollution crisis.

Rethinking value, rebranding waste

The circular economy is an alternative model designed to decouple economic growth economic growth from resource consumption by finding ways to keep products and materials at their highest value for a as long as possible. In doing so, it reduces pressure on natural resources and reduces waste by turning it into new materials instead of pollution and emissions.

The concept of material circularity is not new: industrial researchers began discussing turning waste or by-products into resources in the 1940s. However, it’s only now gaining real momentum. A 2024 study from UNIDO and Chatham House shows just how fast things are moving: out of the 75 national circular economy roadmaps/calls to action/strategies that have been launched since 1999, a staggering 71 of them since 2016.

The technical roadmap: the 9R framework for a circular economy

To put circular economy into action, the 9Rs framework, proposed by Potting et al. in 2017, offers a clear roadmap, albeit not an easy one. The framework proposes a hierarchy that ensures materials are maintained at their highest value, with R0 representing maximum value retention, and R9 the lowest.

The framework begins with the most impactful actions: Refuse (R0), Rethink (R1), and Reduce (R2), which focus on smarter product use and manufacture. R0 is about rejecting unnecessary consumption entirely, while R1proposes a complete rethink of the need for outright ownership in favour of sharing or leasing in a Product-as-a-Service (PaaS) models. PaaS models incentivise designing for durability and repair as the manufacturer retains ownership and responsibility for the product throughout its life (e.g. leasing lighting systems, or appliances). R2, refers use fewer resources to make a given product, or replacing them with non-virgin materials.

In the middle tiers (R3 through R7), we have actions that extend a product or material’s lifespan, through reuse, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing, and repurposing. The final two, Recycle (R8) and Recover (R9), are concerned with the useful application of materials, with energy recovery through incineration as the last resort.

What are the 9Rs, and why are there 10 of them?

For those of you paying attention, that means our beautiful 9R framework actually has a total of 10Rs, slightly confusing, perhaps, but this choice is not without meaning. R0 is the refusal of new products altogether and rejecting unnecessary consumption. It challenges us consider if we can avoid the use of new materials all together by asking us the fundamental question: is it truly needed? R0 aims to stop the cycle before it begins.

- Refuse: Saying no to unnecessary products or materials

- Rethink: Designing radically different sustainable products, such as Products as a Service models.

- Reduce: Making products more efficient and using less materials

- Reuse: Giving the product to another person for the same use

- Repair: Fixing a broken product to extend use

- Refurbish: Restoring an old product to work like new

- Remanufacture: Taking parts from an old product to build a new one with the same function

- Repurpose: using parts from an old product to build something new with a different function

- Recycle: Processing materials into high quality secondary raw materials

- Recover: Generating energy from materials that cannot be recycled.

However, for the most impactful suite R – first two tiers of this technical framework – a massive cultural change is required. R0 and R1 challenge our relationship with consumption, and for key middle tier R-steps to succeed we have to move away from the linear aesthetic to a circular one, in which a seamless pristine condition is not a prerequisite to beauty.

A new aesthetic of permanence and change

In the field of architecture and construction, this aesthetic change is essential. The global built area is expected to double by 2060, according to Architecture 360, and given our annual extraction rate is already well above what the planet can safely provide us, we need to find ways to build that do not require new resources.

Technical innovations in circular materials are providing opportunities to replace virgin materials with high quality Secondary Resource Materials (SRMs), such as the EU-funded ICARUS project which is piloting new recycling and upcycling methods for construction. However, taking the 9R framework to heart means we also need to aim higher on the ladder to and rethink how we build in the first place.

Designing for Disassembly

Designing for Disassembly (DfD) is a core principle for operationalising material circularity in the construction sector. DfD changes how we view our buildings, from a structure destined for demolition after its useful life is over, to flexible “material banks” – a concept popularised by the EU-Project Building’s as Material Banks – full of valuable components that can be easily accessed and removed.

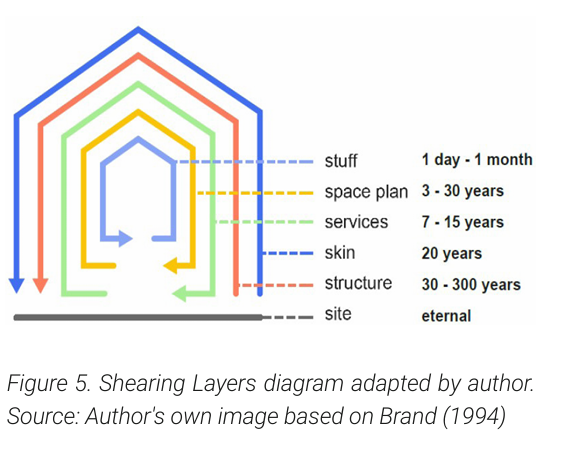

DfD is rooted in the understanding that not all parts of a building age equally. Architect Frank Duffy first introduced the concept of “Shearing Layers”, which separates a building into different layers characterised by their longevity. The concept was later elaborated upon by Stewart Brand in his popular book “How Building’s Learn: What Happens After They’re Built,” to define six layers: site, structure, skin, services, space plan, and stuff.

In viewing building through this lens, we can see exactly why DfD is necessary. Maintaining the maximum material value requires fast-changing layers be easily detachable and replaceable without compromising the slow-changing ones. This means favouring non-destructive reversible mechanical connections so that the structure to adapt to changing needs, be it updating the “skin” to optimise for energy efficiency, or removing the space plan to repurpose a commercial building for residential use.

DfD works by relying on modularity and reversibility favouring mechanical connections (dovetail joints, bolts, clips, demountable footings) instead of permanent ones (welding, glue, poured concrete, glue). In doing so, it ensures both that the components can be accessed and taken apart easily as well as preventing damage to the materials and preserving their quality so that they may enter the next stage of their 9R journey.

The circular aesthetic

This technical necessity creates a whole new aesthetic, one of resilience and adaptability. It means embracing patina, the natural changes that materials undergo over time such as copper turning green or wood weathering grey, as well as the markers of a structure’s adaptability, like visible steel connectors. The beauty lies not in the fixed form, but in its potential for change, to be reconfigured, or disassembled its components used in novel ways elsewhere.

This aesthetic flies in the face of the modern pursuit of flawless, pristine surfaces and the linear economy’s perpetual demand for newness. Instead, it champions an aesthetic rooted in Wabi-Sabi – in finding beauty in impermanence and imperfection. The building’s beauty is in its proven longevity and visible history of adaptation, not it’s immaculate condition.

Examples of this can be seen in projects across the globe: using weathering steel which oxidises to a stable protective layer or featuring reclaimed timber and exposed connectors to make the structures modularity and material history a central feature of the design.

Much like Kintsugi, these design approaches proudly share the history of an object, celebrating the visible changes and joints, and the meaning behind them. Beautiful because, not because despite.

The golden seam: beauty in resilience

Ultimately, the success of a truly circular economy for the construction section depends on simultaneous cultivating a compelling circular aesthetic that celebrates a material’s life story and longevity.

The beauty lies not in the fixed form, but in its potential for change, to be reconfigured, or disassembled its components used in novel ways elsewhere.

And here lies the opportunity: objects that use reused materials have a unique, traceable history that new materials simply lack. When designers highlight the origins and journey of these materials, they elevate “reused” (or any of the Rs for that matter) into a premium design feature that appeals directly to consumers desires for something unique and meaningful.

The circular economy is an invitation to architects, designers and consumer alike to embrace a new form of beauty. In a world where every patch of patina, visible bolt serves as a gold-lined symbol of adaptation, affirming that beauty is not found in the seamless and new, but in the story of resilience and endurance.