Understanding Hydrogen’s Climate Impacts

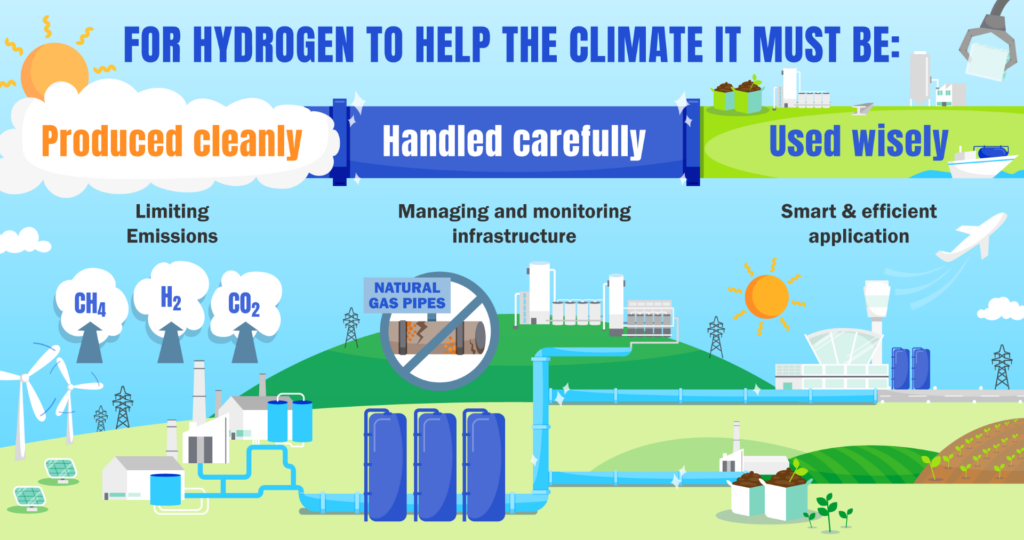

Hydrogen could help combat climate change – but only if we produce, manage, and use it wisely. Here’s why.

Clean hydrogen has generated significant interest as a key player in the clean energy transition. The EU prioritises the development of renewable hydrogen, recognising its crucial role in the energy transition, net-zero goals, and sustainable development. The 2022 REPowerEU Strategy set a target of producing 10 million tonnes and importing another 10 million tonnes of hydrogen by 2030.

Between 2021 and 2027, the EU has allocated an estimated €18.8 billion to hydrogen-related projects. This funding is distributed across various programs, with the Recovery and Resilience Facility and the Innovation Fund being two key sources of financial support.

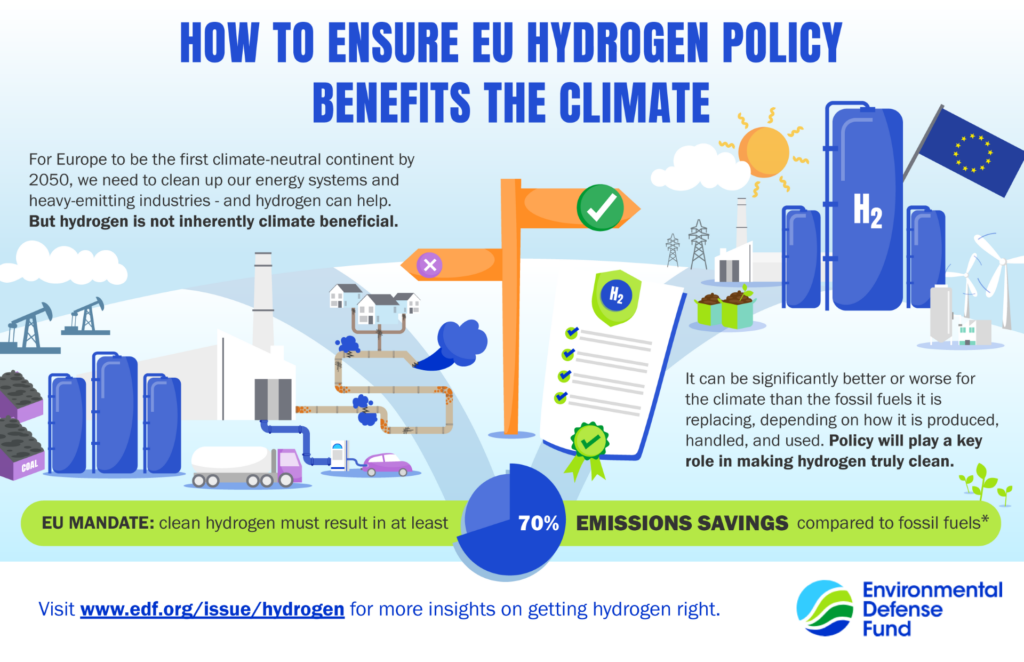

However, this investment may not meet all its climate mitigation potential if we do not understand that hydrogen’s cleanliness is not guaranteed – and critically what we need to do about it.

Clean, careful, and clever

Hydrogen has real potential as a source of clean power but to make hydrogen an effective climate solution, we must consider how it’s produced, managed, and used. To start, regardless of how hydrogen is produced (with fossil fuels or renewable energy as two main pathways), it is energy intensive, and results in emissions. Additionally, hydrogen, as the smallest molecule on earth, leaks easily, and though it doesn’t directly warm the planet – it is an indirect greenhouse gas – when it’s released, it increases the amount and lifespan of other potent greenhouse gases, such as methane, ozone, and water vapor. It’s also a short-lived pollutant, so its climate impact is particularly significant within the first 20 years after it’s emitted. During that time, hydrogen can be 37 times more powerful than CO₂ in terms of its warming potential.

The Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) aims to support policymakers and decision-makers in both public and private sectors to maximise the benefits of future hydrogen systems. “One area of focus in our hydrogen work is its emissions and the resulting climate implications – a topic that remains niche and is often overlooked by many stakeholders,” says Anna Lóránt, Senior Policy Officer at EDF.

According to the EU mandate, clean hydrogen must achieve at least a 70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to the fossil fuels it replaces. When assessing whether this target is met, it’s essential to also consider hydrogen’s climate impacts in calculations. From a policy perspective, this matters because decisions made today – such as those regarding hydrogen production, infrastructure, and deployment – will shape our energy systems for decades. To ensure hydrogen systems contribute positively to the energy transition, policy must promote clean hydrogen value chains, accurately accounting for all climate-warming emissions, including not only carbon dioxide (CO₂) and methane emissions from fossil-based hydrogen but also hydrogen itself, adds Lóránt.

Where clean hydrogen gets deployed is another important aspect of getting hydrogen right. Today’s hydrogen demand – primarily in the refinery and chemical sectors – is almost entirely met by hydrogen produced from unabated fossil fuels, which has an important climate impact. In 2021, more than 900 million tonnes CO₂ emissions were associated with the global hydrogen value chain. “To put this into perspective, if hydrogen were a country, it would rank among the top 10 global emitters, with emissions greater than countries like Germany,” Lóránt says, adding, “this means that, right now, hydrogen is more of a climate problem than a solution. Cleaning up our existing hydrogen production systems should be the number one priority. At the same time, ongoing discussions about where to use and where not to use hydrogen are critical.”

One clear example is using hydrogen for home heating, which is frequently debated. “If you compare green hydrogen (produced from renewable electricity) with direct electrification for heating, hydrogen would require seven times more energy on average,” Lóránt asserts.

From a policy standpoint, it’s crucial to recognise that clean hydrogen is a scarce and expensive resource. Policies should ensure it’s directed toward uses where other more efficient solutions are not available.

Anna Lóránt

Communication challenges around hydrogen

“There’s no denying that hydrogen has generated a lot of buzz over recent years – and for good reason. It genuinely may be our best path to decarbonise the tough-to-electrify sectors – if it’s done right. But there’s also a lot of ambition based on the perception that hydrogen is always clean – or has no climate impact. Some of the enthusiasm is missing a grounding in scientific evidence,” affirms Ciel Jolley, Communications Director for Hydrogen at EDF.

Hydrogen’s climate benefit isn’t absolute; it’s on a spectrum. Good decisions can maximise its emission-reduction potential, while poor ones could limit or even negate those benefits. “If we ignore the technical realities, we risk taking shortcuts and realising years down the road that hydrogen didn’t deliver the benefits we’d hoped for,” adds Jolley.

No one knows how much hydrogen is being lost into the atmosphere. Current estimates are based on simulations and modelling, not empirical data. Hydrogen is the smallest molecule on Earth, even smaller than methane, and EDF’s experience with methane leaks show that containing such molecules is extremely challenging. Current estimates of hydrogen emissions vary widely, from less than 1% to as high as 20%, but the empirical evidence on the actual losses from existing systems is lacking.

One main reason for this gap is that commercially available hydrogen detection technologies have prioritised safety, focusing on preventing large leaks rather than smaller, more consistent losses that when added up can impact the climate. However, innovative sensors, with the necessary speed and sensitivity, are now being developed, and the landscape is evolving quickly. The European Commission has launched several research initiatives over the past few years, and not-for-profits, like EDF, are also advancing this work.

“This year, we will be kicking off a first-of-its-kind comprehensive study to measure and quantify hydrogen emissions across the value chain in North America and Europe. It is a unique and collaborative partnership with academia, science and technology, and industry partners with the goal of bringing valuable new understanding and data to industry and policymakers. The International Energy Agency (IEA), the Department of Energy (DOE) in the U.S., and the European Commission have in recent years acknowledged the need to better understand the quantity and impact of hydrogen emissions through improved technology, measurement, and collaboration – so we should expect to see the flourishing of a robust ecosystem working to solve this challenge,” says Jolley.

Many people still assume hydrogen is simply clean. Only a few years ago, no one was talking about the potential risks. What people need to understand is that it can be very clean, or it can be very dirty. Now there’s growing awareness that we need to be careful about how we make, manage and use hydrogen.

Ciel Jolley

When discussing hydrogen, maintaining a positive outlook on its potential while ensuring factual and transparent communication is essential. EDF’s approach is rooted in science and evidence. They work towards providing clear, data-driven insights to support policymakers, investors, and industry leaders in making well-informed decisions.

What can policy do?

“The ultimate goal here isn’t to build a hydrogen system for its own sake – it’s achieving a cleaner, safer, more secure energy system and ultimately climate neutrality,” Lóránt adds. In the European context, hydrogen is a means to contribute to that goal. Some decision-makers assume that simply building hydrogen infrastructure or meeting production targets automatically drive climate benefits, which isn’t necessarily true.

“As we engage in these discussions, we try to bring nuance and keep the climate objective at the forefront,” Lóránt states.

Lóránt emphasises the need for strong policies to address hydrogen emissions effectively. First, mitigation measures should be mandated to ensure that best practices are in place across the value chain. Even simple, immediately-actionable steps, such as tightening valves and seals, can significantly reduce emissions and should be required as standard practice.

In addition, enforcing monitoring and leak detection is crucial. Robust monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems, along with leak detection and repair (LDAR) protocols, must be integrated from the outset of hydrogen system development. The experience with methane emissions from the oil and gas sector has shown the dangers of overlooking losses (both intentional operational releases and unintentional leaks) – methane went undetected for decades, causing severe climate damage before policies finally began to address the issue. A similar mistake should not be repeated with hydrogen.

Furthermore, greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting must accurately incorporate all climate-warming emissions. In addition to carbon dioxide and methane emissions, EU-level rules should explicitly recognise hydrogen’s climate impact, ensuring that all stakeholders in the hydrogen value chain have a clear incentive to measure and mitigate emissions proactively.

Finally, supporting research and innovation is essential for improving hydrogen emission detection and understanding its broader climate implications. Allocating resources through programmes like Horizon Europe can help close critical data gaps and drive technological advancements. Investment in these areas will be instrumental in developing effective solutions for a cleaner hydrogen future.

Hydrogen’s promise lies in its climate potential

Hydrogen has the potential to play a vital role in the energy transition, but realising its benefits requires a science-based, evidence-driven approach. From addressing emissions in existing hydrogen production to ensuring effective policies for monitoring, mitigation, and innovation, every step must be taken with climate objectives in mind. Poorly developed and managed hydrogen systems could undermine climate progress rather than advance it. As Lóránt and Jolley emphasise, decision-makers must remain transparent, nuanced, and strategic in how hydrogen is produced, handled, and used.

Ultimately, hydrogen’s promise lies in its potential as a climate solution. Overlooking the science that will help us achieve that goal could defeat the very purpose of pursuing hydrogen in the first place – so we need to get it right.

Ciel Jolley