Western Sahara

Keeping the status quo alive

UN resolution 1979 (2011) on the Western Sahara does not bring independence any closer for the Saharawi people; it does not even improve human rights; it merely endorses the Moroccan monarchy.

Resolution 1979 (2011) on the Western Sahara

Since December 2010, the so-called international community watches the popular protests taking place in the Arab world. In the midst of a global economic crisis, these revolts – hitherto unimaginable and unimagined – are the result of the desperation of societies in the face of entrenched corruption and the authoritarianism of regimes founded on oligarchies that seized power during their independence. Nevertheless, the revolutionary outbreak owes, without doubt, its rapid local and regional propagation to the expansion of communication amongst the youth (via Internet networks), which breaks the iron silence of information upon which such regimes were founded. The first achievement of these protests was the deposition of Ben Ali in Tunis. The trigger of his demise was the self-immolation of a young man haunted by his own future and the constant arrogance and humiliation of the regime.

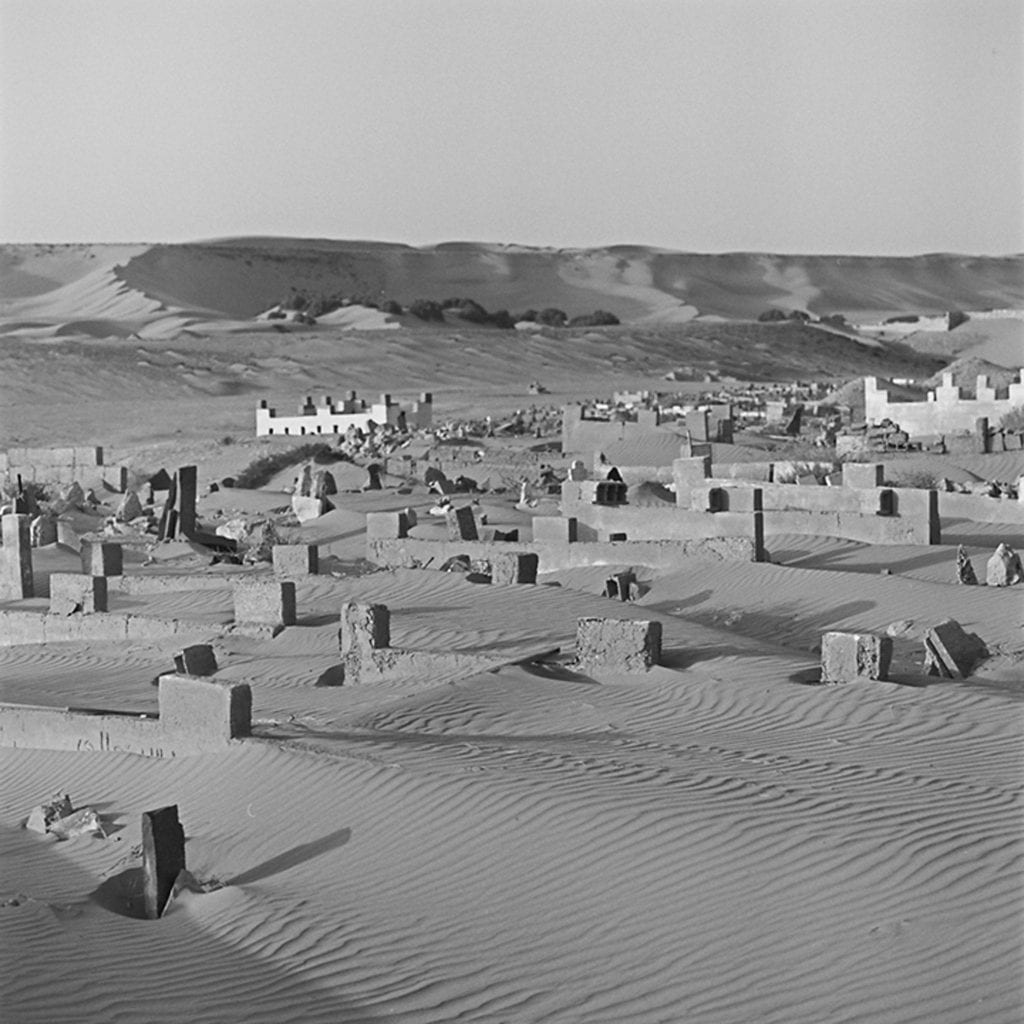

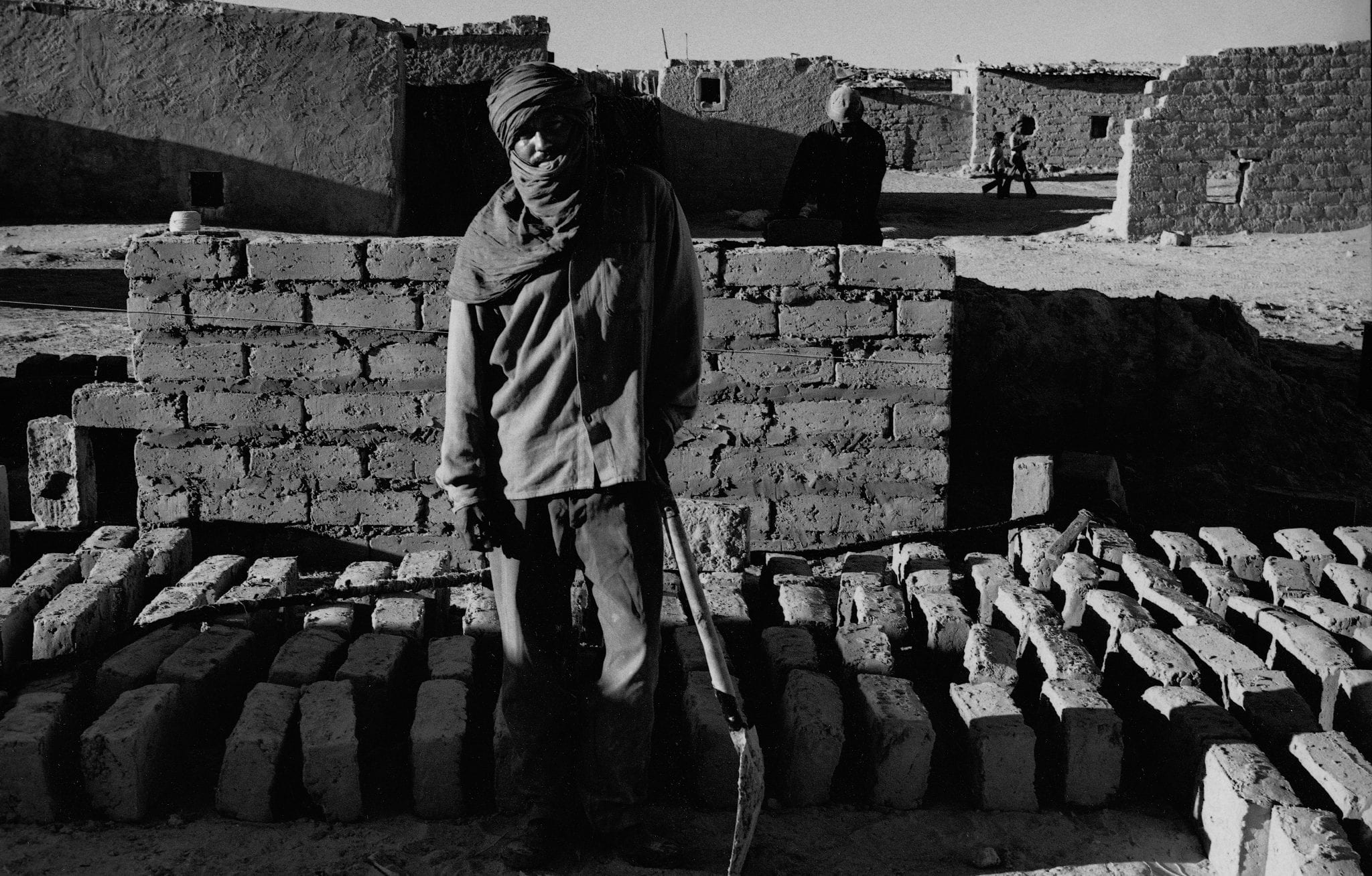

However, the first warning signs of this tide of demonstrations took place in early October 2010, several thousand kilometers from the Mediterranean, in the extreme south-western point of the Arab world, in El-Aaiun – the capital of Western Sahara. Prohibited from demonstrating peacefully in the city streets, thousands of Saharawis, dodging Moroccan occupation forces, pitched their tents in Gdeim Izik – the middle of the desert – and protested against their lack of work and housing, and demanding their rights to sovereignty over the natural resources of their territory.

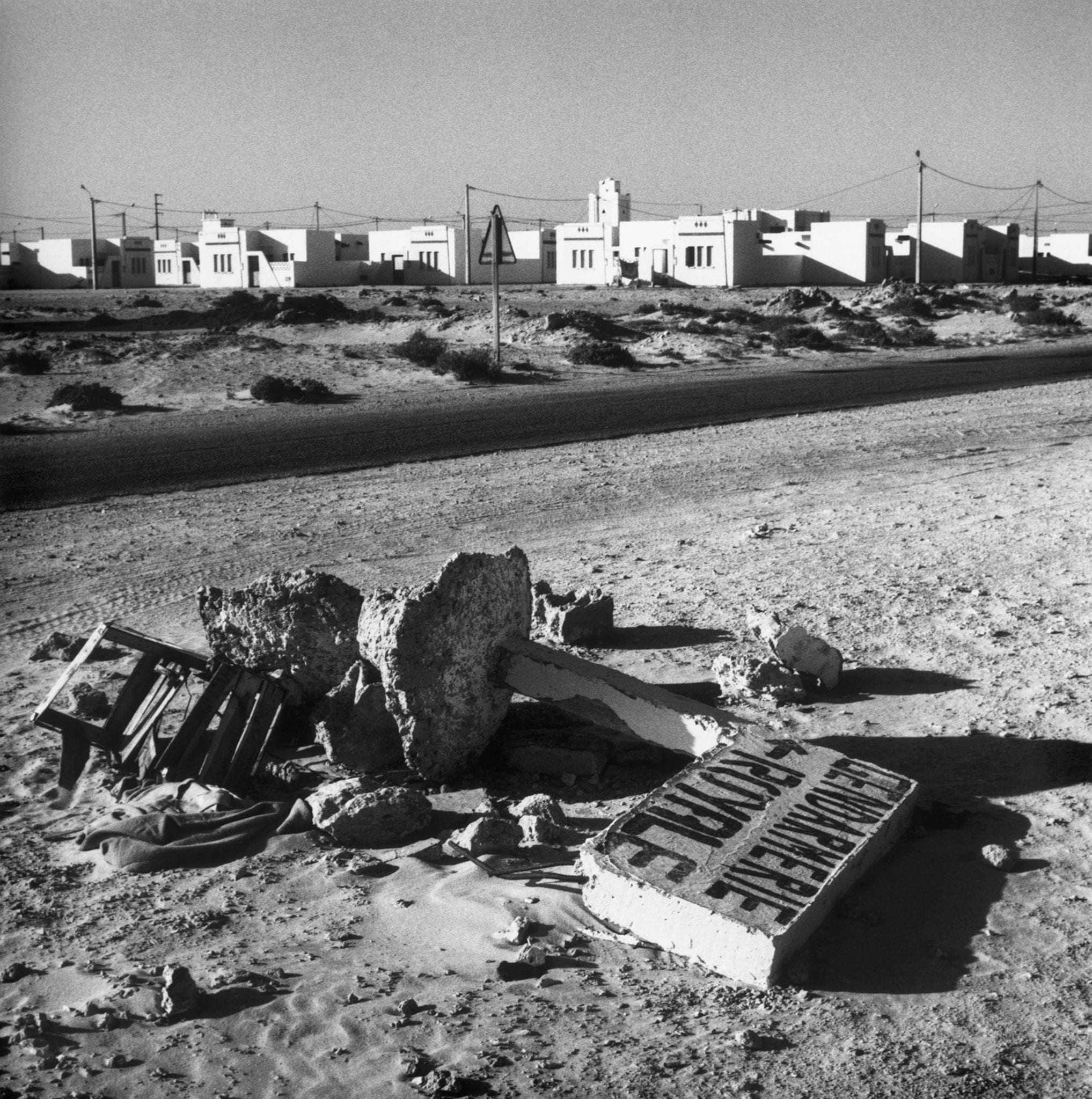

The Moroccan monarchy, overwhelmed by the magnitude of the events and the deterioration of its international image, reacted, making use of what has become a classic formula: first, expulsion of the international press to avoid uncomfortable testimonials, followed by the assault on and destruction of the encampment on November 8, 2010, followed by the detention, and disappearance of opposition leaders without due process. But this time, some members of the Moroccan Security Forces died along with protesters.

The young Saharawis who lived in the zone of Western Sahara that is occupied by the Moroccans – desperate after waiting for a referendum allowing them to choose freely their future for more than 35 years – had lost the fear to die and faced the occupier, brandishing kitchen knives.1 Meanwhile, in the Algerian refugee camps, the Polisario Front2 (the Saharawi Liberation Movement) had to calm its own, also desperate group that threatened to break the ceasefire and intervene on behalf of their brothers.

The Polisario – another oligarchy in power since the foundation of the Movement in 1972 – preferred to offer a new oppor- tunity in the framework of negotiations established by the United Nations. They hoped that their gesture of good faith would be rewarded at the next Security Council resolution which reviews the conflict annually and would include the protection of human rights desired by MINURSO3 – the sole UN peace mission without competencies in human rights.

Recall that Western Sahara is, according to the UN, “a non-autonomous territory,” that is to say, a colonial territory still awaiting decolonization. In October 1975, the Inter- national Tribunal in The Hague rejected any and all sovereign rights of Morocco and Mauritania over the territory.4 However, Spain – the administrative legal power – just a few days later, signed a treaty5 with Morocco and Mauritania ceding administration and thus abandoning its responsibilities. Those agreements were never endorsed by the General Assembly and thus lack all legal effect at the international level. Confirmed by a UN legal report in 2002,6 Morocco and Mauritania became the occupying powers of the Western Sahara in 1976 with the consent of Spain since it was the previous administrating power.

The war that ensued between the occupiers and the Polisario Front initially led to the defeat of Mauritania in 1979, which abandoned the territory. The conflict became a war of attrition in the desert. Morocco managed to hold on to Saharawi cities in order to build a defensive wall protecting nearly 80 percent of the territory – mainly with the help of France (Morocco’s former colonial metropolis and trading partner). In 1991, the exhausted parties agreed to commence negotiations to observe the referendum to-be for self-determination. But Morocco challenged the census prepared for this very purpose in 1999 by MINURSO. From this moment on, conversations have continued without any concrete progress towards the achievement of “a just and sustainable, mutually acceptable, political solution,” which would allow for the self- determination of the Saharawi peoples in accordance with the UN Charter.

Recall that Western Sahara is, according to the UN, “a nonautonomous territory,” that is to say, a colonial territory still awaiting decolonization.

Human rights – On standby

Paradoxically, this stalemate of the negoti- ations has run in parallel to the emergence of human rights groups in Western Sahara cities, which denounce the grave human rights violations committed by the Moroc- can Occupation Forces. The activities of these organizations have been harshly repressed by Morocco, to the point that in November 2009, the internationally renowned Saharawi defender of human rights, Aminatu Haidar,7 was expelled from the territory. Haidar was able to return only after a long and painful hunger strike and effective pressure from the United States.

Despite the ever-decreasing situation and Moroccan repression, the last resolutions in 2009 and 2010 of the Security Coun- cil regarding the territory have ignored the necessity to protect Saharawi human rights. Instead, these resolutions have merely confirmed the importance of progressing in the “human dimensions” of the conflict, as if an analogy exists between the Saharawi conflict and Europe during the Cold War.9 Therefore, after the events of the Gdeim Izik protest encampment, the new UN Security Council resolution regarding Western Sahara was expected with much anticipation.

The new resolution 1979 (2011), like the previous resolutions, was pre-planned by France and Spain, as well as negotiated by the United States, to be adopted finally by the Security Council on April 27, 2011. Its content proves highly disappointing: the resolution does not amplify the MINURSO mandate to the supervision and monitoring of Saharawis’ human rights. The resolution goes so far as to make an unsubstantiated claim to justify a concern for the human rights’ conditions as serious in the zone occupied by Morocco, as in the Algerian refugee camps where the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has an ample presence.

To guarantee the future amelioration of human rights for Saharawis, the Security Council declares that the Resolution and the Security Council will welcome the establishment of a National Council for Human Rights by Morocco, complete with a special chamber dedicated to Western Sahara. This new institution merely renames the pre-existing and inefficient Advisory Council on Human Rights10 created in 1990. The Resolution therefore does no more than implicitly recognize the competence of a public Moroccan institution in a territory outside of its sovereignty, subject to a still pending decolonization process sponsored by the UN. ated in 1990. The Resolution therefore does no more than implicitly recognize the competence of a public Moroccan institution in a territory outside of its sovereignty, subject to a still pending decolonization process sponsored by the UN.

Moreover, the Resolution contains an irrelevant reference to the commitment of Morocco to ensure unconditional access – free of conditions and obstacles – to all the Special Procedures of the UN Advisory Council on Human Rights. This organ is not an objective nor independent institution, but rather it is of a political and inter-governmental nature, having been formed by the representatives of 47 states — including France and Spain — whose governments are characterized by minimal sensitivity to human rights violations of the Saharawis, in addition to other states characterized by indifference towards human rights, such as China, Cuba, or Saudi Arabia. In this sense, it suffices to recall the Universal Periodic Review, to which Morocco was subject in 2008 by the UN Advisory Council on Human Rights, whose final report11 solely recognized progress without once mentioning the dire situation, which already existed, in the occupied territory of Western Sahara.

Endorsing the Moroccan Monarchy

The icing on the cake of this Resolution is that – as a solution – it endorses the application of a refugee protection program developed by the UNHCR in coordination with the Polisario Front. This program, led by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), includes capacity-building and awareness-raising activities on human rights. However, despite these initiatives, the Resolution does not require a similar and indispensable program for the authorities and Moroccan Occupation Forces present in Western Sahara. Morocco is not part of the Statute of the International Criminal Court, nor of the Optional Protocol of the International Convention Against Torture, nor of the International Convention Against the Forced Disappearance of Persons. Morocco is supposed to respect the 1949 Geneva Conventions on International Human Rights, which requires occupying powers to respect the rights of the occupied.

Currently, the Security Council, with all its cynicism and the likely worsening of the situation, recently requested that the Secretary-General inform the Council regu- larly – “at least twice per annum” – of the progress in negotiations between parties. As pre-established by the OHCHR,12 almost all the human rights violations committed in the occupied zone are a consequence of not applying the fundamental right to free selfdetermination of the Saharawi people. What underlies this decision – just as in all the Security Council interventions on this issue since 1991 – is the clear intention to protect the stability of the Moroccan Monarchy, considered by the United States since its independence in 1956, as an essential ally against Communism previously and currently against fundamentalist Islam.

This blind protectionism of a dictatorship is no way to guarantee local or regional stability, but rather the complete opposite, as demonstrated by the fall of Ben Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt, as well as the mass protests in Syria, Jordan, Algeria, and of course Morocco. Since February 20, 2011, every month we have witnessed daily protests in major Moroccan cities calling for democracy and an end to the abuses of corruption. Mohammed VI and his entourage, pressured by their French partners, have not gone beyond a cosmetic reform of the system. The new constitution, which only superficially cut the king’s absolute powers, was approved in a recent referendum – as in previous elections. Barely 30 percent of the voting-age population participated due to abstention from leftists and fundamentalists, who are surprisingly united in all the claims of the Arab protests.

Every month we have witnessed daily protests in major Moroccan cities calling for democracy and an end to the abuses of corruption.

The Moroccan Monarchy’s anecdotal reformism and the blind protection of the Security Council appear to move in the same direction: in the face of new challenges, and using the words of the Prince of Lampedusa in The Leopard (1958), ‘change so that nothing changes’. Introducing a standard for democracy in institutions and speaking of human rights in resolutions regarding the Western Sahara are always desirable – if, and only if – the effective control of the king and his political-economic-military entourage in Morocco over the Saharawi territory and its natural resources is not threatened. However, in both scenarios, the prudish and short-term strategy may soon be over-taken by events. The Arab people are taking their destiny into their own hands in opposition to the special interests of their oligarchies and the reductionist interests of the great powers.