Securing A Sustainable Future With Our Ocean

Balancing nature and people across Earth’s final frontier.

206 million Europeans live on a coastline, likely sharing a sense of wonder and possibility when casting their eyes out onto the world’s last frontier. But this wide-eyed view comes tinged with a dark stain: through common colonial narratives of expansion, we have been led to perceive this vast blue expanse as an immense, unidimensional “white canvas” where human activities such as fishing, offshore oil and gas exploitation, shipping, and more can grow without limits, even if the limit has already been reached for many valuable ecosystems. But while the ocean occupies over 70% of our planet, we still only know less than 5% about all its ecosystems. Even with new discoveries made each year, this knowledge gap means we still don’t fully comprehend the impacts of human actions on vulnerable species and habitats.

While most coastal livelihoods are tied to the ocean, online searches of human activities in the Atlantic region show idyllic coastal living, not images of the thousands of fishing and sand dredging vessels, kilometers of undersea cables, heavy presence of oil rigs and growing plastic islands.

The ocean occupies over 70% of our planet, but we still only know less than 5% about all its ecosystems

Although evidence of humanity’s continued overexploitation of nature may not be readily visible, it does not mean that these activities are not there and in a very big way: OECD projections show that by 2030 the “blue economy” – our exploitation of marine resources for sustainable economic development – could outperform the growth of the global economy as a whole, both in terms of value-added and employment. In the EU, the gross value-added of the blue economy grew by 10.41% between 2009 and 2019 and today it employs 4.45 million people (2.3% of the EU’s total population).

It is vital to remember that our deltas, sea basins and ocean are common goods – no single person or entity owns them. However, national governments do have sovereignty over the first 200 nautical miles off their coastlines (a country’s exclusive economic zone, or EEZ), and their public policies significantly impact the development of human activities and the protection of marine biodiversity, both within national boundaries and outside of them on the high seas.

Given the critical status of our ocean in light of the twin climate and biodiversity crises, coupled with its interconnected nature across man-made borders, long term strategies for sustainability that are supported by robust planning and management tools are more needed than ever before.

The EU’s Directive for maritime spatial planning (MSP) acts as the foundation for coherent management of the EU’s marine area and provides a formal structure for scientific knowledge to support how Member States develop strategic national plans for regulation, ‘zone’ various industries at sea and protect the marine environment.

The EU’s approach to planning is uniquely valuable because it is the most comprehensive maritime policy being implemented globally, and because it brings all interested people together to decide our blue future.

MSP: a tool for sustainable ocean governance

MSP started as a management approach for nature conservation in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park 50 years ago. Over an area bigger than the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Switzerland combined, policymakers sought to develop legislation that would save the reef from oil drilling and mineral extraction while permitting other activities like fishing and tourism in specified areas. The ripples of this work have reached far beyond the Great Barrier Reef: in the past 25 years, over 74 countries have started trialing or fully practicing MSP as an effective approach to managing human activities and nature protection in their marine areas.

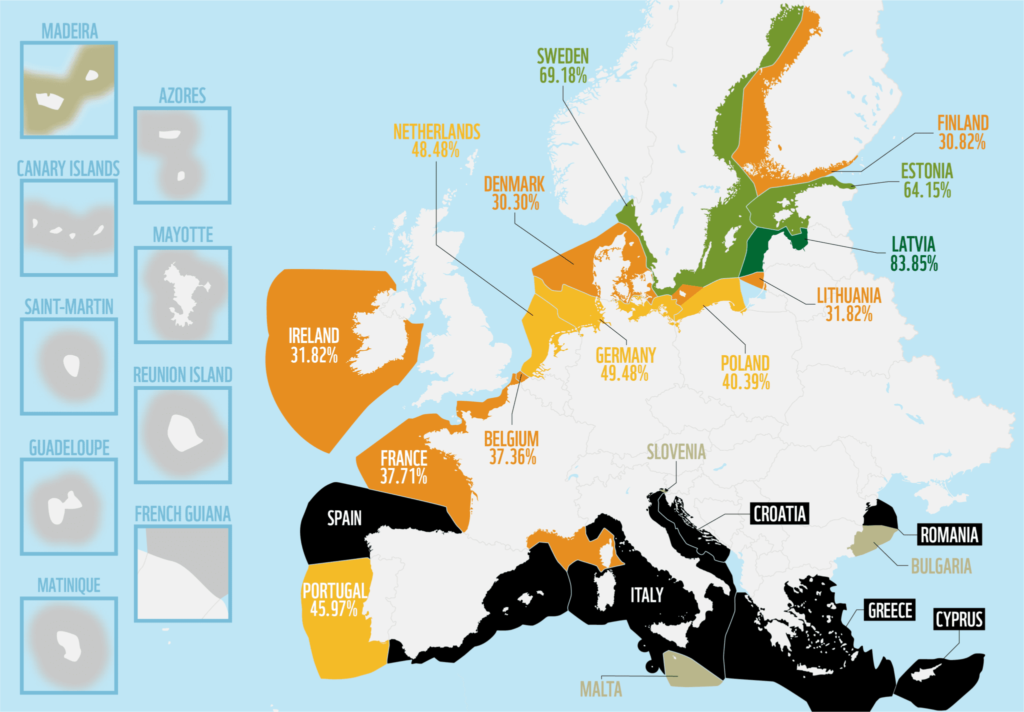

However, not all plans keep maritime activities in balance with people’s social and economic interests, or in harmony with conservation of an area’s natural and cultural integrity. For example, in the EU, Member States are required by law to apply an ecosystem-based approach to MSP, meaning they must consider the ecological boundaries of marine ecosystems when allocating space to different human activities; however, WWF research has revealed that the national plans in place don’t adequately consider nature’s limits to economic development. Further, they have different interpretations of what an ecosystem-based approach requires. The result is an incomplete approach to MSP and a lack of harmony between activities in each European sea basin.

For MSP to support a sustainable blue economy successfully, it needs to be a forward-looking process that considers all economic sectors and ecological factors related to a marine area. Then, space needs to be allocated both geographically and over time, to different activities and people whose livelihoods are tied to our seas. This is particularly important in light of EU commitments to speed up the deployment of offshore renewable energy, which is essential to deliver a carbon-neutral future and achieve the 1.5ºC Paris Agreement target. As the ocean is the Earth’s largest carbon sink and with the EU boasting the biggest maritime territory, there is an opportunity for a new wave of positive MSP ‘ripples’ to be felt around the globe.

MSP in the EU

Promisingly, in the EU, MSP works as a link between industries tied to our seas. It allocates space for different maritime activities while also having a broader say over long-term national and regional visions for a sustainable blue economy. As MSP supports how social, economic and environmental priorities are translated into the physical occupation of space at sea, it is a crucial tool for good ocean governance – a high-level word used to define the integration of policies, actions and affairs contributing to how the ocean is protected and accessed by all of us.

Most importantly, MSP does not replace the policies to effectively manage maritime activities across different sectors, nor does it replace the need for effective and well-managed marine protected areas that serve as refuges to valuable and vulnerable ecosystems. Instead, it helps to create and support the political conditions for developing and evaluating networks of well-managed protected areas in harmony with other at-sea activities. This is important because the accelerating impacts of climate change in our ocean make protecting the “right” places like biodiversity hotspots and wildlife migratory corridors imperative.

Because national maritime plans take a long time to develop, they also stay in place for extended periods of time – usually between six and ten years in the EU. That’s why it is so crucial to get them right, and to collect data over the course of a plan’s implementation period to generate the knowledge essential for creating more effective and inclusive plans in the future.

Member States’ existing plans are insufficient for the EU to deliver on its climate and biodiversity goals.

Inclusivity is a key point of successful MSP. While it is ultimately up to the national authorities what elements are included in the final strategic document, embracing opportunities to improve the planning process via new information and diverse perspectives from marine-affiliated communities and industries can help mitigate the impacts of climate change, support the transition to sustainable seafood consumption and boost cooperative management of protected areas.

Importantly, nothing prevents countries from redesigning their plans as soon as new data or priorities emerge. This flexibility has proven key in Denmark, with the government deciding to kick-start the MSP process all over again following the backlash from civil society over how economic interests triumphed over nature protection. Hopefully, with the present need to speed up renewable energy deployment and address biodiversity collapse in EU seas, more countries will follow Denmark’s example and improve their existing plans as soon as possible to reflect geopolitical priorities.

The state of planning in European waters

Despite the EU having the tools for sustainable ocean planning enshrined in law (which is still very unique from a global perspective), Member States’ existing plans are insufficient for the EU to deliver on its climate and biodiversity goals. European Commission research also shows that the objectives of the European Green Deal, the EU’s policy package to deliver the first climateneutral continent by 2050, are not integrated with Member States’ national maritime plans. This is completely at odds with EU ambitions to be a global leader in climate action.

Climate change isn’t the only area where countries are lagging behind in their plans: there has been a struggle across Member States to prioritize how their marine areas are accessed and shared by different sectors, including traditional ones like fisheries, while still leaving space for “future uses” such as tidal and wave energy, expansion of protected areas, and more.

Fisheries, which is one of the most long-standing and influential maritime industries, and responsible for a big chunk of the EU’s blue economy (10% of 2019 gross profits), is just one activity that stands to lose from poor MSP processes. As planners tend to follow an approach that prioritizes “fixed uses” such as wind turbines which are usually anchored to the sea floor and for a long period of time, more “mobile industries” like fishing are overlooked.

Without the participation of fishers in MSP, it is nearly impossible to safeguard a sustainable future for the industry. These stakeholders bring with them both a feel for what is happening in our seas via inter-generational learnings and invaluable data about the health of fish populations, as they are legally required to report what they catch.

The pièce de résistance for our ocean’s health is how to successfully integrate protected areas in MSP. Less than 30% of EU seas are allocated for the protection of marine life, despite all Member States pledging to do so by 2030 under the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sharks, dolphins, whales and numerous other species in serious decline are not sufficiently protected in Europe, and very few efforts are underway to actively restore the habitats essential to their existence and help fight climate change through carbon capture. When nature loses, we do too.

Underlying all challenges is the actual implementation of the MSP law across the EU. As of December 2022, six Member States, five of which are in the Mediterranean region, have yet to implement a national maritime spatial plan. This leaves one of Europe’s most iconic sea basins without the tools to develop activities like the deployment of offshore renewable energy in a sustainable and forward-looking way. It is essential for national governments to focus on finalizing these plans as quickly as possible, without side-lining important steps such as comprehensive consultations with all interested stakeholders. For those Member States with a national plan, it is urgent that upcoming policies, such as REPowerEU and the Nature Restoration Law are implemented in line with the MSP process, and that plans are updated to reflect the much needed action on clean energy and conservation.

The further we delay implementation of nature restoration and conservation, the heavier the price tag: the current trajectory of biodiversity destruction will cost the global economy as much as US$2.7 trillion a year by 2030 and the longer we wait to act, the more difficult it will be to solve climate-related problems such as food insecurity, unemployment and loss of nature, to name just a few.

This is no longer exclusively an environmentalist argument: economists are now objecting to the commodification of nature (the idea that nature exists only as an ‘object’ that can be used as an input in the production chain) and debunking the colonial myth of unlimited marine resources. They’re also speaking out on the need to protect our blue commons, the planet’s final frontier, from the threats posed by extractive and exploitative policies that deplete our ocean of life and the resources on which we all depend.

Learning to surf the MSP wave

The challenge now is deciding how to move forward. How can we step out of this one-dimensional view on MSP that plots economic activities without consideration for future changes, and that not only excludes nature but vulnerable communities too? In the EU, it is urgent that Member States talk to each other and invest in a dynamic, collaborative approach to planning that involves people and non-EU neighbors throughout the whole process.

Today, MSP is the best solution for addressing the multiple problems our ocean faces. The way the EU’s law on this process was developed allows for growth and improvement. What we need now is the political will to keep Paris Agreement promises and achieve European Green Deal ambitions in harmony with EU Biodiversity Strategy goals for nature restoration and protection.

Renewable energy expansion in the world’s largest marine area must go hand-in-hand with the recovery of degraded marine ecosystems. We can’t have a climate-neutral future without our ocean’s natural resources, but we also can’t have a healthy ocean unless we curb climate change and its destructive impacts. Fundamentally, ocean action is climate action.

Finally, it is crucial to open the processes of how we plan our blue future to communities often excluded from decision making. Our ocean belongs to all of us and, in turn, its health depends on all of us. It is everyone’s responsibility to be part of the MSP process and to have their say for good ocean governance. To ensure that future generations can grow up looking at the sea with the same sense of wonder many of us feel today and that countless numbers of people have felt throughout history, we must deliver a balance between nature and people.

To effectively restore and protect our ocean as per the EU Biodiversity Strategy, achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 with the European Green Deal, and put legal and sustainable seafood on our plates in line with the CFP, we need rigorous, ambitious and long-term strategies – and we need them now.

But no Member State is currently on track to meet the minimum 30% MPA and 10% strict-protection targets by 2030. Space for nature protection and restoration is also not well integrated in today’s national maritime plans, but these are essential to sustain the EU blue economy and improve coastal resilience to climate change.

Ecosystem-based Maritime Spatial Planning is the right tool to secure harmony between sectors and address the dual biodiversity and climate crises. With the world’s largest maritime territory, the EU must lead by example.