Why Smart Cycling Still Isn’t Moving Forward

Europe talks a big game on smart cycling, but without data, funding, or political will, the wheels aren’t turning.

It’s time to stop celebrating electric bike demos and digital dashboards and start confronting the uncomfortable truth: Europe’s smart cycling agenda is stalled by its systems.

The organisation at the Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS European Congress) in Seville was impressive and the intentions were sincere. I was happy to finally find a solid session on cycling after after hearing so much about electric vehicles and autonomous cars, which can sometimes be too technical for a journalist. The session titled “The potential for smart cycling for Europe: a strategic roadmap” included slide after slide laying out the promise of smart cycling: seamless integration, real-time data, healthier cities. It all sounded visionary until the next slide detailed the same structural obstacles that have haunted European mobility for decades: lack of funding, poor integration, low public awareness, fragmented digital systems, and political inertia.

In other words, we know where the future is, we just need to pave the road to get there.

A digital divide on two wheels

Smart cycling promises to integrate biking into ITS, with data flows as smooth as urban bike lanes are intended to be. But here’s the catch: the data doesn’t exist or isn’t shared.

According to the presentations in the session, there’s “little available data,” no structural funding to collect it, and “data quality, standardisation, and system operability” are all lacking. This doesn’t seem like a technical limitation, but rather a political one. While cities across Europe have embraced electric scooters with corporate partners collecting reams of data, public cycling infrastructure is left in the digital shadows.

While cities across Europe have embraced electric scooters with corporate partners collecting reams of data, public cycling infrastructure is left in the digital shadows.

Even where data initiatives do exist, like the Overijssel cycling app in the Netherlands, they remain scattered. Other promising but isolated examples include Zwolle’s Sniffer Bike project, which collects air quality data through citizen-participating cyclists; Copenhagen’s Variable Message Signs that display cyclist counts in real time, and priority systems for bike couriers using intelligent traffic lights.

These efforts collect valuable behavioural and environmental data and help nudge cyclists toward smarter habits, but they’re still isolated experiments in a system that desperately needs scale and connectivity.

Smart on paper, not in practice

Stephanie Kleine, from the Ministry for Environment, Nature, and Transport in north-Rhine Westphalia, Germany made it clear: Smart cycling should be “as integral to urban mobility as smart solutions for motorised traffic.” Yet, we continue to treat cycling as a social movement rather than a backbone of mobility.

Take Belém and COP30’s greenwashing controversies and apply them here, the parallels are uncanny. Europe’s cities love symbolic gestures, such as bike-to-work days and decorative lanes in tourist centres. But what is “smart” about cyclists in real neighbourhoods lacking safety, signal priority, or integrated navigation systems?

A highway project moves ahead quickly, but a plan to share cycling data across borders gets stuck in political meetings.

A highway project moves ahead quickly, but a plan to share cycling data across borders gets stuck in political meetings.

Ecosystem or echo chamber?

Stephanie Kleine calls for a thriving ecosystem, where “companies, cycling organisations, researchers, and authorities collaborate.” But what we have is patchwork.

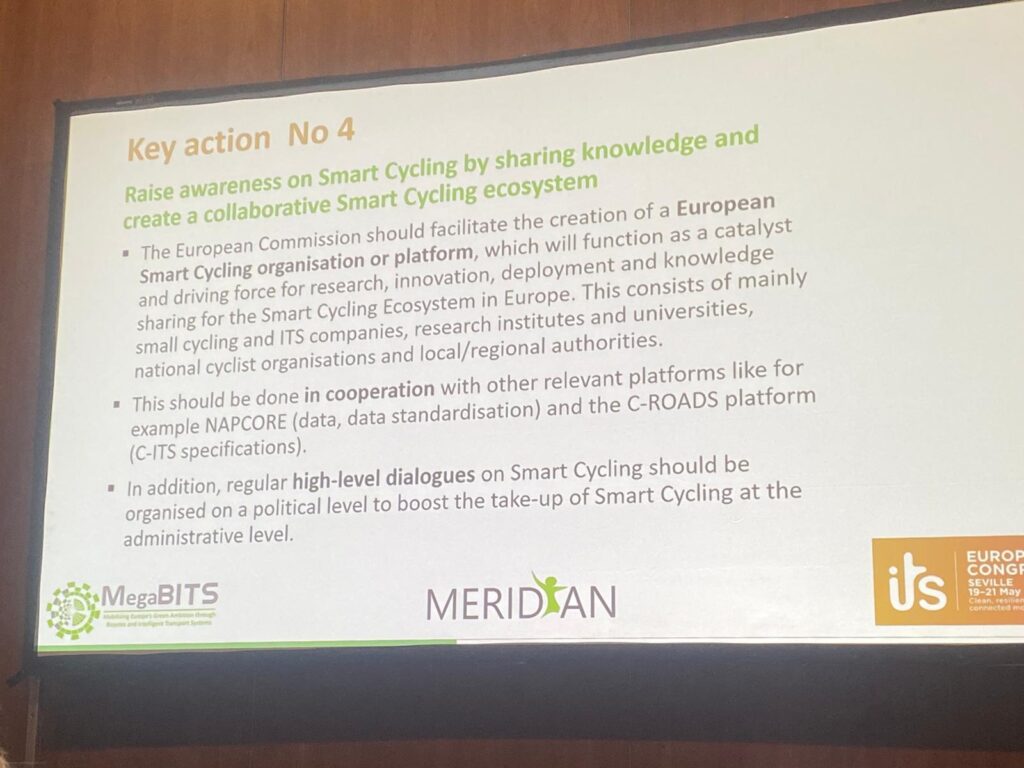

There is no central European platform to consolidate smart cycling efforts. The suggestion to create one is buried under “Key Action No. 4” when it should be Step Zero. Until platforms like NAPCORE and C-ROADS open the gates to cycling data and coordination, we’re not building an ecosystem; we’re curating a closed-loop innovation echo chamber, as I felt during many sessions of ITS 2025.

Funding the future

The financing gaps are painfully familiar. Few funding calls, minimal structural support, and little budget for pilots. Worse, the “economic value of cycling data is unknown,” a telling admission of how undervalued this entire sector still is. As Meridian Corridor indicates in its roadmap, dedicated funding is required for research, development, pilot projects, and the implementation of smart cycling solutions.

If smart cycling is to be more than a presentation fantasy, it needs investment on par with motorised transport infrastructure. That means embedding cycling in national and EU transport frameworks instead of tacking it on as an afterthought.

There’s good news. Technological readiness is high. Public interest is rising. Health and climate benefits are beyond dispute, and we see more and more constructive examples like Zwolle’s Sniffer Bike project or Copenhagen’s Variable Message Signs. Yet the progress stalls.

Why? Because Europe remains entrenched in a car-first mindset, even when developing smart mobility strategies. Smart cycling isn’t missing tools; it’s missing political will.

The message from Seville is clear: the time for smart cycling is now. But without bold leadership and integrated action, it will remain stuck in the slide decks of fancy conferences.

And the road to a truly smarter Europe will remain stubbornly naive.