Digital Inclusion Versus Planetary Good?

A False Dichotomy: The convergence of data proliferation and environmental concerns prompts a reevaluation of global priorities

Data is critical in the global AI arms race for governments and industries. States are heavily investing in collecting citizen-generated data to optimize the value of public services. Companies compete fiercely for consumer data, viewed as scarce resources. In the last decade, institutional attention has shifted to the Global South where 90 percent of the world’s youths reside. Affordable smartphones and data plans have pushed these ‘next billion’ users online for the first time and they have become avid consumers and creators of digital data.

While aid agencies and governments celebrate such growing access as bridging the digital divide, climate activists sound the alarm about what indiscriminate data collection, storage, and use may mean to the fate of our planet.

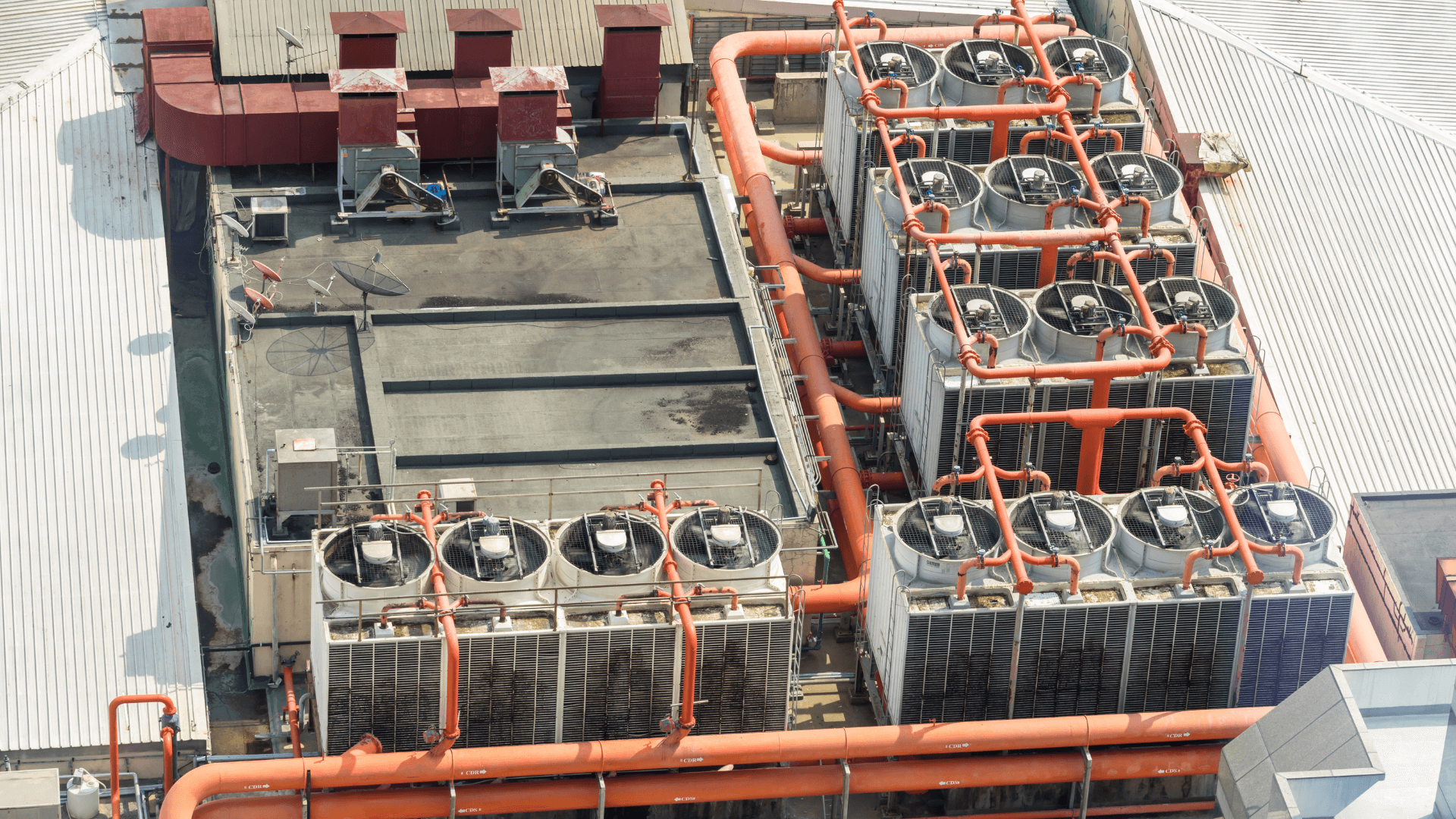

Data is the ‘new oil’: Data centers have a bigger carbon footprint than the aviation industry. Far from being abstract, invisible, and intangible, data is very much physical and resource-consuming. The cloud is grounded by cables and concrete. From sensors to streaming, our everyday digital tools demand a slice of the energy pie. Moreover, the data war is the new water war. Data centers demand enormous amounts of already scarce water to cool their systems, often at the cost of the local communities’ basic need for water to survive.

Pitting digital inclusion against planetary preservation though, is not the answer.

Data is the ‘new oil’: Data centers have a bigger carbon footprint than the aviation industry

Framing this relationship as oppositional is misleading and unhelpful. It prevents an honest reckoning of the West’s legacy of resource extraction and consumption, and current practices of indiscriminate data harvesting. Climate and data justice need to go hand in hand – both vying for an equitable distribution of value and responsibility between the North and South of our physical and digital resources. We need to invest in innovations for data-lite technologies and renewables, especially for and by the Global South. We should enforce existing data regulations on indiscriminate data collection and embrace an inclusive approach to translate AI-driven precision into prosperity for people and the planet.

Climate meets data Justice

Environmental activists especially in the Global South call for ‘climate justice,’ to equitably redistribute the burdens and benefits of addressing climate change, prioritizing communities most vulnerable to its impact. The world’s wealthiest 10 percent produces up to 50 percent of the planet’s consumption-based carbon emissions, while the poorest half of humanity contributes only 10 percent. We have a problem when an American fridge uses more electricity than a typical African person. Western hypocrisy runs deep. Rich countries advocate for clean energy while importing fossil fuels. They can afford to be organic, ‘go local,’ and celebrate their air quality while dumping their e-waste in the Global South.

Aid agencies offer loans at debilitating interest rates for clean energy, often leaving African countries with little choice but to consume coal or look to their Asian neighbors for investment. Blanket treatment of different contexts in the name of sustainable design can exacerbate inequality and entrench poverty. While the rich world is preoccupied with making clean energy, countries in Africa are focused on producing more energy—their pathway out of poverty.

Likewise, AI activists call for ‘data justice,’ the fair and ethical treatment of individuals and communities’ data when it comes to collecting, processing, and use. There is a push to de-bias data that is used to train AI systems to ensure that they work fairly for everyone. While typically the West has been preoccupied by the data deluge and the need to slow down and even turn off the flow, the rest of the world is more focused on the data deficit, the vast black holes of data missing about the Global South.

AI activists call for ‘data justice,’ the fair and ethical treatment of individuals and communities’ data when it comes to collecting, processing, and use.

This invisibility can create further misrepresentation, discrimination, and alienation of those already at the margins from future markets and societal opportunities. For instance, Brazilian tech reformer Ronaldo Lemos explains that by being unmapped, people living in the favelas have limited access to public services: “They don’t have an address, so they don’t get mail at the post office. You don’t get garbage collection, you don’t get electricity. That’s the reality.”

The degrowth movement’s advocacy of ‘voluntary’ downscaling of consumption and production is tone-deaf to the realities of disadvantaged populations living with minimal means of survival. Being frugal as a choice versus as a social condition is contingent on your socio-economic reality. Moreover, it is false to assume an incompatibility between socio-economic mobility and environmental care. The degrowth movement fails to take heed of how Indigenous cultures approach dignified living and planetary well-being as symbiotic and fundamental to their place in the world. By extension, we can learn to explore ways in which the digital and planetary can become compatible and mutually reinforcing.

Indigenous design

We need to think and do differently if we are to address the formidable challenges of social and planetary wellbeing. We can learn from care practices among Indigenous communities in the Global South. Striding forward does not always mean leaving the past behind. There is value in culture for computing a future. We need to dive deep into diverse cultural contexts to avoid reinventing the wheel.

Indigenous communities are not ‘too poor to be green.’ Greening is not something their people ‘do,’ but is essentially how they live. Time to acknowledge that sustainability is indigeneity writ large.

While Indigenous peoples constitute 6 percent of the global population, they protect 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. The Sámi people living in the Arctic, for instance, can teach us coexistence through their core principle of eennâm lii eellim (land is life), which shapes their everyday behavior with nature. Many Indigenous communities across the world share similar worldviews in which nature enables their culture’s existence. This stands in contrast to Western extractive perspectives that commodify nature to serve their people.

Indigenous communities are not ‘too poor to be green.’ Greening is not something their people ‘do,’ but is essentially how they live. Time to acknowledge that sustainability is indigeneity writ large.

Note: This essay is built on ideas from the upcoming book by the author with MIT Press/Harper Collins India – “From pessimism to promise: Lessons from the Global South on designing inclusive tech.” This section was written as a Rockefeller Bellagio Resident in 2023.