The People Protecting the World’s Last Rainforests

Stopping deforestation requires more than targets, it demands trust, justice, and resources reaching people on the ground

Stopping deforestation means backing the people who protect the world’s biggest rainforests every day. In this interview, Cool Earth’s Acting Head of Policy and Advocacy speaks with Ahmetcan Uzlaşık and Phatsimo Ditlhong about the feature Cool Earth was featured called “ The bold model stopping deforestation in its tracks” about community-led rainforest protection, why unconditional cash works in practice and what global diplomacy, lobbying and climate politics mean for the world’s last great forests.

Phatsimo: To start us off, can you introduce yourself, your role and what you do?

My name is Martin Simonneau and I’m the Acting Head of Policy and Advocacy at Cool Earth. We are a UK-based climate charity working directly with Indigenous peoples and local communities across the Peruvian Amazon, the Congo Basin in Cameroon and the forests of Papua New Guinea. These communities have stewarded and protected their territories for thousands of years, and they are now facing intense pressures from loggers, extractive industries and sometimes from government policies that do not respect their lands or their rights. My work focuses on the stories, science and justice issues that shape these forests and on ensuring that Indigenous peoples remain at the centre of climate solutions.

Ahmetcan: Where is deforestation happening most intensely right now, and where does Cool Earth work on the ground?

Deforestation is happening across all tropical forest regions. The Brazilian Amazon gets the most attention, but enormous losses continue in Peru, where we work, especially in areas affected by logging and extractive industries. In Cameroon in the Congo Basin, communities are facing expanding concessions, infrastructure projects and land pressures. In Papua New Guinea, where most land is held under customary ownership, people are confronting illegal logging, land grabs and industrial activity. Rather than ranking which region is worst, it is important to recognise that the issue is severe everywhere. Across all our partner communities, people face similar threats to their territories, forests and ways of life.

Phatsimo: What makes Cool Earth’s model of direct, unconditional cash more effective than traditional conservation or offset approaches?

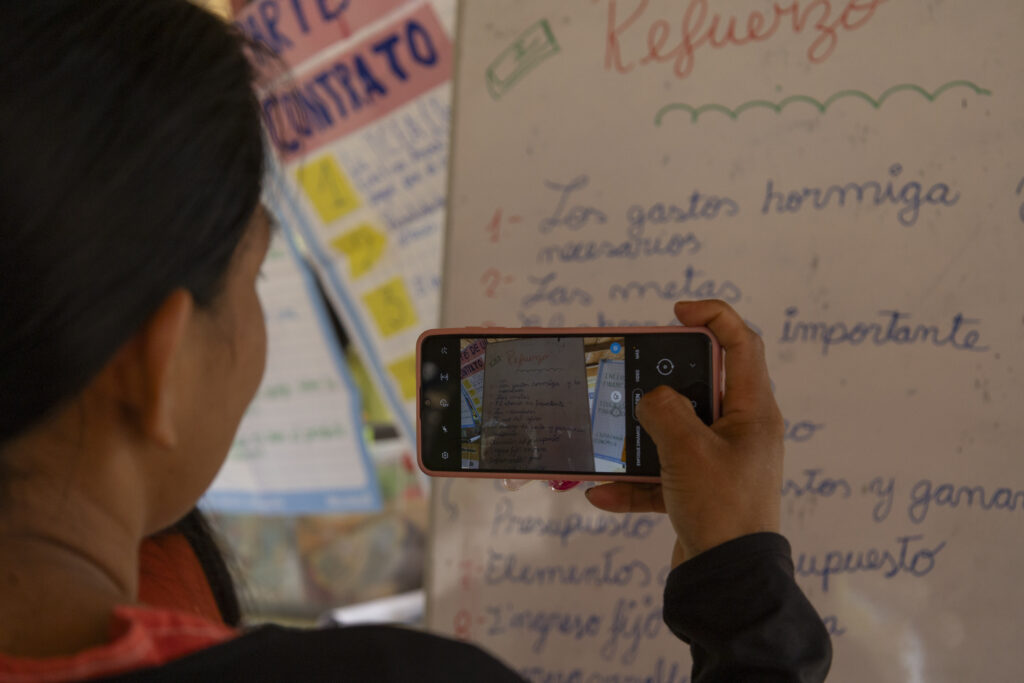

The model came directly from communities themselves. In the mid-2000s, Cool Earth was connected with an Indigenous community in the Peruvian Amazon that was being repeatedly approached by loggers. Instead of proposing a pre-designed conservation project, we listened. What they asked for was direct, unconditional support to strengthen their resilience and protect their forest. That became the foundation of our approach: getting resources as quickly and efficiently as possible from donors to the people facing the threats, without layers of intermediaries.

That directness is what sets it apart from offsets or traditional conservation. Offsets often impose complex conditions and involve multiple agencies. We remove those barriers. Communities know their own priorities, whether it’s food security, education, emergency needs, equipment, wildfire response or monitoring their territories. Those priorities can change daily, and a distant institution cannot adapt at that pace. Cash is fast, flexible and respects community autonomy. These are the people who have protected rainforests for millennia. They know how to make the most out of even small payments.

Ahmetcan: How do you ensure these cash transfers strengthen communities long-term rather than creating dependency?

Cash influences long-term wellbeing even after payments stop. When a family invests in a child’s education, that impact lasts for decades. When they use cash to start a small business, buy tools or improve food security, that income or resilience continues. At the community level, cash can fund infrastructure like health posts, water systems or communications equipment that supports the whole area long-term.

In Peru, where Indigenous governance structures are strong, we sometimes deliver larger unconditional payments to Indigenous federations. They’ve used these to develop new practices for climate-adaptive agriculture as slash-and-burn becomes riskier in a hotter, drier climate. This kind of work has long-lasting benefits.

None of our programs are simply about transferring money. Everything is co-created with community leaders, participants and governance bodies. Communities map their structures, design objectives, decide delivery mechanisms and choose how resources are allocated. Because programs are embedded within local systems and priorities, they build autonomy instead of dependency.

Phatsimo: What are the main challenges you face when engaging communities and delivering support?

The first challenge is simply working in rainforest environments. In Papua New Guinea, for example, someone may need to trek for hours to reach a mountaintop where there is mobile signal. This is also true for communication, program design and logistics. Every community is unique, and even neighbouring communities can have completely different needs and governance structures. Designing a program that is flexible enough to respect that diversity requires time, trust and careful collaboration.

Another challenge is working with donors. Many funders still struggle to release money at the speed required for frontline protection. Reporting requirements and bureaucratic controls slow things down. For cash-based models to scale, we need more flexible funding that matches the urgency of deforestation.

There is also the issue of intermediaries. In the climate and conservation space, it’s common for money to pass through multiple organisations before reaching communities. These institutions often take a share of budgets. Our model deliberately minimises this. We’ve shown that money can move quickly, transparently and directly to communities. Scaling that approach means convincing larger funders and institutions that this is both possible and effective.

Ahmetcan: People outside rainforest regions often feel disconnected from these issues. How do you communicate why rainforests matter to someone living in Europe or elsewhere?

Rainforests stabilise the global climate. They regulate rainfall, influence temperature patterns and support food systems. When they disappear, the consequences ripple everywhere: droughts, floods, extreme heat, food shortages and health impacts. Even if someone lives far from the tropics, their life will be affected by rainforest loss within the next decade. Our campaign work, including our December campaign, focuses on showing exactly how forests in places like Papua New Guinea or Cameroon matter for people in London, Brussels, Istanbul or anywhere else.

Phatsimo: With global drivers like agriculture and trade still pushing deforestation, can community-led interventions scale fast enough or do we need systemic economic change too?

We need both. Community-led action is essential, but it cannot do everything. The underlying problem is structural: the global economy still values trees more when they are cut down than when they are standing. That is a fundamental market failure and it needs to change.

We also need stronger supply-chain regulations, including rapid implementation of the EU deforestation regulation, which has already been delayed. And the food system must be redesigned so it no longer drives large-scale forest destruction. At the same time, there is a justice dimension. The wealth generated from forest exploitation has not benefitted the people who actually protect these ecosystems. Direct cash helps correct that imbalance. It recognises that Indigenous peoples have always been the solution and that their knowledge systems must shape the world we build next.

Ahmetcan: You mentioned COP. How do you see the future of international climate diplomacy given recent geopolitical shifts?

The most recent COP outcome was disappointing, but the fact that a final text was agreed at all still represents some functioning multilateral diplomacy because 196 countries must reach consensus. If you only look at the closed-door negotiations, you may feel pessimistic. But COP is much more than what happens in those rooms. Across the venue you see Indigenous delegations, activists, youth movements, scientists and NGOs bringing forward ideas and pressure. Those voices don’t always appear in the final text, but they shape the political environment around decision makers.

Climate diplomacy is not going fast enough and the process has flaws, but there is still enormous energy and innovation happening both inside and outside formal negotiations. The tools, resources and strategies we need already exist. What we’re missing is political will, not solutions.

Phatsimo: If someone takes only one message from this conversation, what should it be?

Support Indigenous peoples. If you want to contribute to ending deforestation in the most effective way, this is where to start. Their knowledge, stewardship and cultural practices are the foundation of rainforest protection. Direct cash is one of the most efficient, immediate tools for supporting them. And when you support Indigenous peoples, you support climate action, biodiversity protection and human rights all at once.