Imagine the Transarabian Xpress

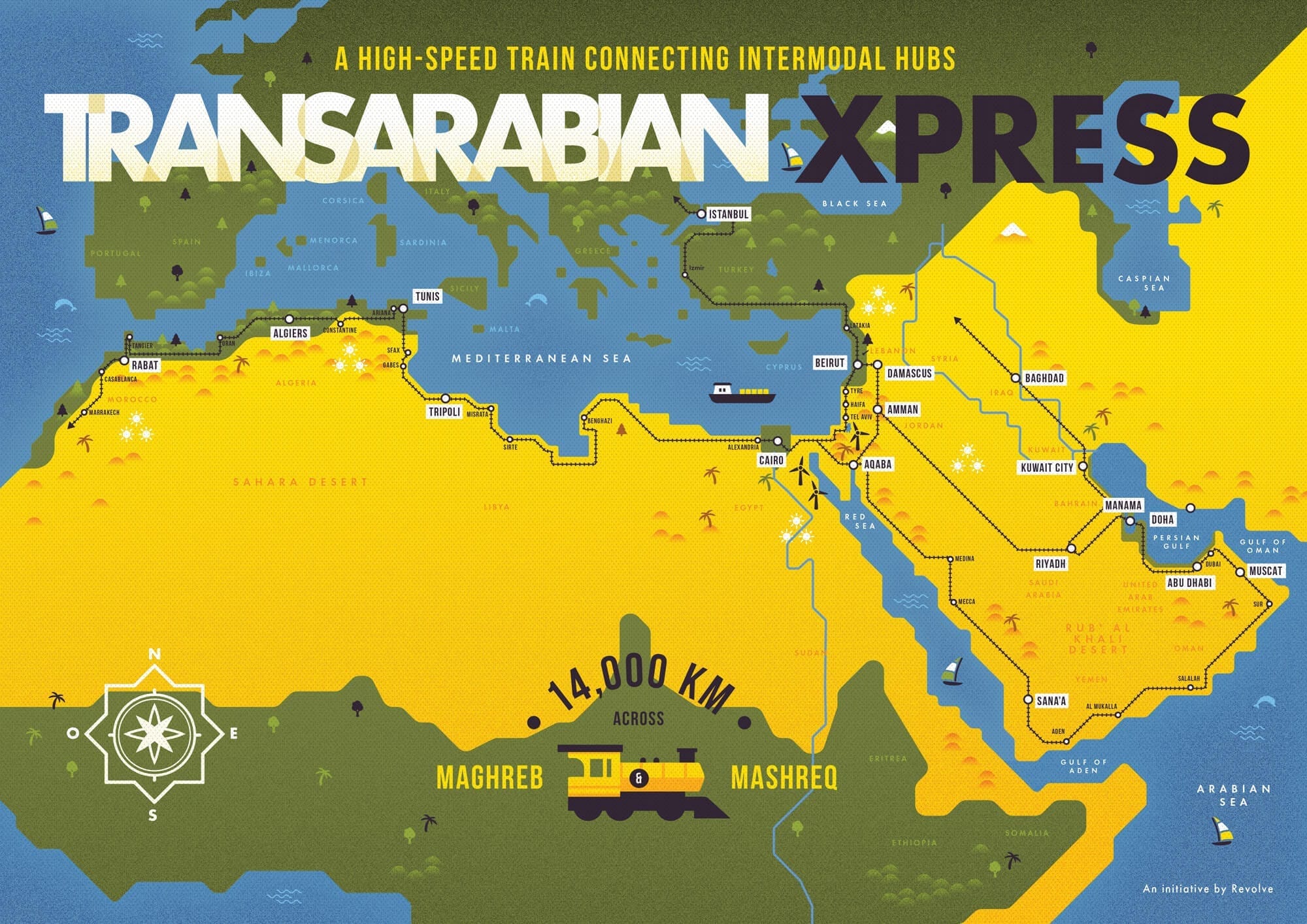

Imagine connecting Morocco to Oman with a high-speed train going across North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula transporting people and goods for tourism, business and commerce.

Imagine a high-speed train that connects countries, cities and citizens across North Africa into the Middle East and the Arabian Gulf. Imagine a high-speed train that would transcend the wall between Morocco and Algeria, the refugee debacle between Tunisia and Libya, the political quagmire in Israel/Palestine, the wars in Syria and Iraq… Imagine a high-speed train powered by hydrogen and renewable energies that travel at 300-400 kilometers per hour from Casablanca to Algiers to Tunis to Tripoli to Alexandria-Cairo-Suez-Aqaba-Amman-Baghdad-Basra-Kuwait-Riyadh-Abu Dhabi-Dubai-Muscat… Imagine a high-speed train that makes stops at other cities, transporting goods and people, creating commerce and movement. Imagine that each station is an intermodal hub with options for public transport, bicycles, and car-sharing – all digitalized on your mobile. Imagine that each station is a historical building renovated in the local traditional architectural style: a blend of the Arabesque and the future mixed together by integrating nature with the digital world of tomorrow.

To contextualize this dream, the first Arab railway was opened in 1854 between Alexandria and Kafar Zayat in Egypt. Thereafter, railways were built in 11 Arab countries. Three major axes emerged in general geographical areas: (1) Maghreb (North Africa) linking from west to east: Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya; (2) the Nile Valley linking Egypt and Sudan; and (3) the Turkey-Red Sea connection linking from north to south Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine to the west, and to the east Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Historically, and the focus of this first leg of the TransArabianXpress journey, we will look at perhaps the most important railway axis called the Hejaz Railway that was built in the early 1900s.

The Hejaz Railway was originally built to transport pilgrims from Istanbul via Damascus and Amman to Medina, where they would travel on to Mecca for the Muslim ‘hajj’ or pilgrimage. The idea was first put forward in 1864 during the height of the age of great railways around the world, but it was not until 40 years later (1908) that the Hejaz Railway came into being. Before the Hejaz Railway, Muslim pilgrims travelled to Medina by camel caravan. The journey between Damascus and Medina usually took two months and was full of hardships. Since the Muslim calendar is a lunar calendar, the feast of Al-Adha, when Muslims travel to Medina to worship the Kaaba (Black Stone) changed from season to season. Sometimes it meant traveling through the winter, enduring freezing temperatures or torrential rains. At the height of summer, it meant crossing scorching hot deserts. Towns and settlements were sparse and there were hostile Muslim tribes along the way, as well as the inevitable bandits who preyed on pious pilgrims, as they made the ‘once in a lifetime’ pilgrimage.

As word spread that the pilgrimage had just become easier, business boomed, and by 1914 the annual load had soared to 300,000 passengers.

The building of the Hejaz Railway presented a financial and engineering challenge. It required a budget of some $16 million dollars, and this was at the turn of the century when dollars were worth a lot more than they are today. Contributions came from the Turkish Sultan Abdul Hammed, the Khedive of Egypt, and the Shah of Iran. Other contributions came from the Turkish Civil Service, Armed Forces, and other various fund-raising efforts (which included the sale of titles such as Pasha or Bey to citizens who could afford the price of instant honour).

Construction, maintenance and guarding of the line all presented enormous difficulties. The task was mainly undertaken by 5,000 Turkish soldiers. Along the way there were hostile tribesmen, who before the railway, made a lucrative profit guiding, protecting and providing for pilgrims. They were very unhappy at loosing part of their livelihood. Many of them were pastoralist whose main source of cash was their involvement in the pilgrimage each year. Along with this there were physical difficulties. Driving a railway across the Arabian deserts proved very difficult. The ground was very soft and sandy in places and solid rock in others. There were also major geographical obstacles to cross, such as the Naqab Escarpment in southern Jordan. While drinking water and water for the steam engines was a problem, winter rainstorms caused flash floods, washing away bridges and banks and causing the line to collapse in places.

The camel caravan owners were far from pleased by the construction of the railway line, as it posed a considerable threat to their livelihood. The railway journey was quicker and cheaper, and no one in their right mind would contemplate spending £40 on an arduous, two-month camel journey when they could travel in comfort in only four days for just £3.50. However, frequent attacks on the trains by the tribes and furious caravan operators, made the journey to Medina a perilous undertaking for pilgrims, whether by camel or by rail.

On 1 September 1908, the railway officially opened and by the year 1912 it was transporting 30,000 pilgrims a year. As word spread that the pilgrimage had just become easier, business boomed, and by 1914 the annual load had soared to 300,000 passengers. Not only were pilgrims transported to Medina, but the Ottoman Turkish Army began using the railway as its chief mode of transport for troops and supplies. This was to be the railway’s undoing, as it was severely damaged during the First World War (1914-1918) by Lawrence of Arabia and the Arab Revolt.

After the World War 1 and until as recently as 1971, several attempts were made to revive the railway, but the scheme proved too difficult and too expensive. Road transport was soon established and by the 1970s aviation had made rapid progress. The railway was abandoned and the huge old steam locomotives sat and rusted. Train stations ran into disrepair and dilapidation. No one travelled by train anymore except for a tourist line running from Damascus north to the Turkish-Syrian border, and that too is now closed due to civil strife. But the romance of the railway remains alive today with such projects as the TransArabian Xpress.

Interestingly, the railway never actually reached Mecca and during the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottomans during the First World War, parts of the railway were blown up by Lawrence of Arabia and the Arab allies. Some sections of the railway in Jordan are still in minor use today. Now, Jordan’s railway network is composed of two main railway lines. The Jordan Hejaz Railway Corporation (HRC) uses a railway for touristic purposes as well as for limited passenger trains. The Aqaba Railway Corporation (ARC) was established in 1979 and uses a rail line to transport mainly phosphate to the Port of Aqaba. The total length of the network in operation is about 509 km and is composed of narrow gage track (1050 mm gauge). Since 2010, the government has been developing a new national railway network: the feasibility study is completed and the estimated cost is around $3.5 billion. It is unclear from where these funds will come.