Uranium Mining Resurfaces in Swedish Village

Sweden intends to lift the moratorium on uranium mining in the next few months, and the international mining corporations are rearing to go.

In April 2023, Ida Asp received a letter from the Mining Inspectorate in Stockholm, stating that Bergslagen Metals AS was granted an ‘exclusive permit’ to initiate mining research at the Viken number 2 area in the Berg municipality.

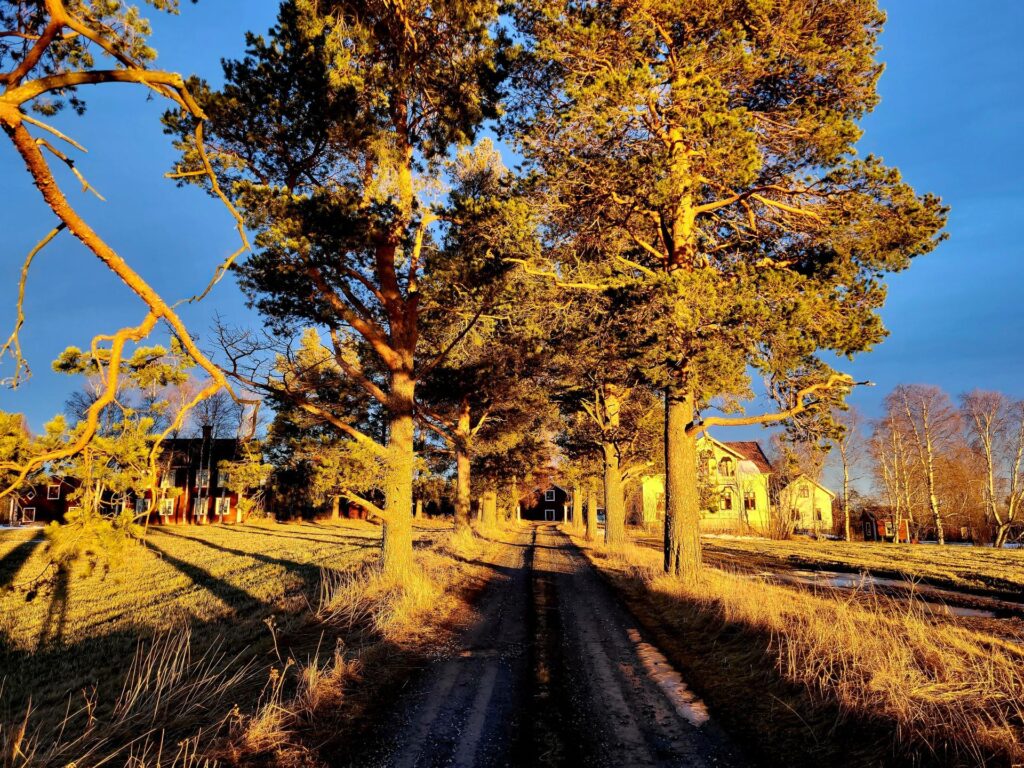

The designated area extends over almost the entire surroundings of Asp’s freshly renovated 18th-century country house, as well as over her whole property in Oviken village, where the alum shales located just under the ground surface are rich in metals and minerals.

Asp works in the civil service, where she oversees the inflow of European funds into Sweden. As the vice president of the Berg municipality council, she is also active in local politics. She and her husband received an offer to purchase their house and its surrounding territory at market price. The Swedish Mineral Act, written in the 19th century, states that anyone can apply for a mining permit anywhere under the surface, only needing to pick a metal or mineral with a solid chance of being found at the designated location, which potentially means that the Swedish land owners are not even the owners of their basements.

Several hundred inhabitants of the idyllic Jamtland region received the same sort of letter – among them landowners, farmers, foresters, and owners of weekend retreats. At the time of my arrival, the region may have been blessed with a rather wonderful thaw, yet many of the residents were consumed with anxiety. Some even feared they would be relocated en masse to a ‘new Oviken’ hastily built somewhere else…much like the inhabitants of the historic mining town of Kiruna.

According to the Geological Survey of Sweden, its central lowlands hold the globe’s greatest reserve of uranium ore. It is also rich in other metals and minerals like potassium, copper, nickel, and vanadium.

Global mining companies have long been aware of potential windfalls. In May 2018, the Swedish parliament passed an amendment to the environmental legislature which instituted a national ban on uranium ore mining and research. The moratorium was put in effect on 01 August 2018.

A survey commissioned by the Ministry of Climate and Enterprise last February mandated a change of rules and set the terms for uranium extraction. The report on the public discussion of the survey needs to be concluded by 20 March 2025. The withdrawal of the moratorium will then be discussed in the Swedish parliament. The changes in the legislature have to be adopted by 01 January at the latest.

According to a variety of sources, there is very little doubt that the Swedish authorities will rescind the moratorium by the end of the year. At the start of the survey, the Ministry of Climate and Enterprise stated that the goal was “to remove a ban that is not needed.” It went on to add that “uranium extraction should be regulated by the same environmental regulations as pertain to the other metals and minerals.”

Even before the survey’s findings were published, State Secretary to Minister for Climate and the Environment Daniel Westlén predicted that the moratorium would be lifted. “The ban on uranium mining will be removed,” Westlén announced last autumn. “It will be possible to extract uranium in Sweden. There is no reason for a ban.”

“If the European Union is to become the first climate-neutral continent, access to sustainable metals and minerals must be ensured,” Romina Pourmokhtari, Minister for Climate and the Environment, stated last summer.

The arrival of mining corporations

The inevitability of the moratorium’s demise was greeted with great enthusiasm from the local proponents of a nuclear renaissance. It was the authorities’ intention to build two new nuclear reactors by 2035 and ten by 2045, while also aiming to entirely de-carbonise Sweden’s electricity in the name of the green transition.

Over the next 30 years, Sweden’s high demand for electricity is expected to double to approximately 300 Terawatt hours, mostly on account of the de-carbonisation of the colossal Swedish iron and steel industry.

Until now, Sweden needed approximately 1,500 tonnes of uranium yearly to keep its six nuclear reactors running. In the decades to come, that number is estimated to rise to 3,000–4,000 tonnes. According to World Nuclear Association data, the world consumes 67,000 tonnes of uranium annually, while the European Union’s yearly usage amounts to 12,500 tonnes.

According to the World Nuclear Association, 65 nuclear reactors are currently being built across 16 countries, while 90 further reactors are in their planning stage. China is once more leading the field.

It is also worth mentioning, however, that over the last two decades, more than a hundred nuclear power plants have been closed all over the globe.

The World Nuclear Association predicts a 33% increase in uranium usage over the next decade, correlating to an estimated 27% growth in nuclear reactor capacities. The experts believe new technologies like ‘fast reactors ‘ could greatly increase the efficiency of nuclear fuel usage. In theory, this should mean that the planet holds enough uranium for almost two thousand years. Another factor to be added is the option of recycling nuclear fuel – though the process is still too costly.

Sweden is of course a member of the Euratom organisation, which supplies uranium to its members while also minding a certain degree of diversification of the supply chain. For several years, Sweden has imported its entire supply of nuclear fuel as the country does not possess the means for uranium enrichment, though that, too, is planned to change.

In the wake of the Russian aggression on Ukraine and Niger’s military coup in July 2023, when the local junta expelled the French and handed control of their uranium mines to Russia, much has changed in the global uranium marketplace.

Numerous international mining corporations have already shown interest in Swedish uranium extraction. The most proactive thus far has been the Canadian District Metals company, which was recently granted uranium research and extraction rights to the entire Viken region when the moratorium is lifted.

Another company worth mentioning is Australian Aura Energy, set to extract uranium ore along the Häggån river, where potassium, zinc, molybdenum, and vanadium are also to be mined. In 2019, Aura Energy sued the Swedish government for damages on account of the moratorium.

“The Swedish government’s stated aim aligns well with the ability to mine domestic uranium, reducing foreign dependency and strengthening domestic and European energy supply,” stated Andrew Grove, who until recently served as the company’s Managing Director. He added: “It is of course essential that uranium is mined in a way that does not threaten the local environment or water supply, and I am certain that we will be able to demonstrate that within the framework of the Swedish permit process.”

In the name of the green transition

“No, hell no! I will not allow them to dig under my house!” Asp declared, seated at the massive wooden table in her enchanting Scandinavian abode, where she aims to live a life of self-sufficiency. Next to her red house, there is a kennel holding ten Siberian husky dogs. Several sheep are bleating behind a fence, accompanied by an Icelandic horse. A pair of dogs and several cats have run of the house.

“As soon as I received the letter, I started making calls. People were furious. The first time I organised a meeting, a hundred people showed up. Even many of those who do not get bothered about the environment were vehemently opposing the mining project. Almost the entire local community came out against it,” Asp described the initial stages of the local revolt.

A day before my arrival, Ida Asp celebrated her birthday. Beforehand, she had instructed her friends and relatives that the most desired gifts would be survivalist books. “You know, books about how to make strawberry jam in the event of nuclear catastrophe!” she laughed. “I am preparing for the future. I no longer buy most of the prevailing illusions. We have screwed up badly. Humanity is not capable of a sufficiently serious U-turn. We are offered only more-more-more solutions when the only answer is less, less, less.”

Asp related that from the moment the letters started arriving, a toxic cloud of anxiety descended over the entire local community. Suddenly, it was impossible to plan for the future.

Soon after the arrival of the first letters, the previous head of the Australian Aura Energy company paid a visit to Oviken. A meeting with the local community was arranged, where more than three hundred people showed up.

“Their managing director was completely unprepared!” Asp recalled with traces of indignation.

“So many of our basic questions simply drew a blank! Even people hoping that the mining projects could bring some good to the region got the impression something shady was going on. And that was why they, too, turned against the authorities in Stockholm and the foreign mining corporations.

All of us got the impression we were about to be duped. You have to understand that the so-called market price for our land is ridiculously low. My husband and I calculated the sale would only bring back half of our investment into renovating the house; which, again, is ridiculous! It is unheard of! So no matter what, we are set to stay. The only way we get moved is by force.”

Recent trends in Swedish politics have also made Asp consider withdrawing from political life altogether. Since the authorities in Stockholm are preparing a veto on local community decisions, Asp views this as an assault on what used to be the world headquarters of democracy and progressive environmental policies.

“If such a thing can happen in Sweden,” she shook her head, “then you can only imagine what goes on in the rest of the world.”

She recently applied for the job of headmistress at a local primary school.

The number of those protesting the mining project rapidly expanded, their cause being strengthened when Naturskyddsforeningen, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation NGO, joined the fight and brought the support of its 200,000 members.

“We immediately knew something was very wrong. We had to react,” I was told by Katja Kristoffersson, head of communication at the local branch of Naturskyddsforeningen in Östersund.

“We’ve been able to obtain an application submitted by one of the foreign companies to obtain the permit to extract uranium in these parts,” she explained. “So we know what is wrong, we know where the holes are. We believe we can still stop the project, which has little to no connection with the green transition. What it is is a gross form of misleading the public in the interest of foreign corporations.”

Kristoffersson was drawn to the conservationist cause through her love of photographing organic food. She works four-hour daily shifts at Naturskyddsforeningen. The other half of her working time is spent shaping ceramics.

“We have lots of ideas on how to fight back,” she told me. “We are preparing a report drawing on the government’s position from 2020 when the authorities clearly stated that this form of mining was unacceptable. The core of our campaign is the threat mining would bring to the environment – above all to the water. The planned mining projects are in the immediate vicinity of Storsjön Lake, Sweden’s fifth-largest lake which supplies water to 60,000 people. Also at risk are the forests and exceptionally fertile farmlands. We are 85% self-sufficient when it comes to food here! But we fear everything is about to get poisoned – the water, forests, soil, our food, everything! In many places where uranium was extracted from shales like it would be here, this was precisely what happened.”

One of those who joined the battle to stop uranium mining in the Jamtland region was Dr. Urban Tirén. The long-serving head of the paediatric department at the hospital of Östersund, now working as a senior consultant, also received one of the infamous letters.

“My motivation for stopping the project is simple,” Dr. Tirén related. “As a doctor, when children get sick with cancer or other severe diseases, I always do everything in my power to help them. I will never give up. And mining in the alum shale is like cancer. It only spreads and spreads, causing great damage. The mining in alum shale has not been proven safe for the environment in any place in the world.”

As a nature enthusiast, he likes to spend as much time outdoors as possible, preferably in the company of his grandchildren. As a photography enthusiast, he is intimately familiar with the local forests, meadows, lakes, and rivers. He is afraid that the pending mining projects could irreparably damage local wildlife, the water of lake Storsjön, and agricultural production in Jamtland with its fertile soil.

In his opinion, a single mining permit could trigger a domino effect. The entire region could be turned into one widespread excavation site. The winter’s stillness would be replaced by dust and noise, and the Northern Exposure-like quality of living here would be gone forever.

“In my younger days, I spent a lot of time working as a doctor in Africa – in the Central African Republic, for example. And I can recall very well the extent of devastation the mining companies left in their wake,” Urban Tirén continued.

Dr. Tirén fears the loosening of the environmental legislature could ultimately turn Sweden into a Scandinavian Amazonia. The local population sees the mining projects as the continuation of internal colonisation. In Sweden, this process reached its height in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, with mining playing a highly prominent role.

Geopolitical turmoil

The recent developments in Sweden must be understood in the context of recent developments in Brussels. December 2023 saw the European parliament pass The European Critical Raw Materials Act, devoted to ensuring a safe and sustainable supply of said materials. Last August, Sweden signed a huge nuclear agreement with the United States – the so-called strategic partnership mandating the joint development of “small modular reactors” aiming to improve the current practices of managing nuclear waste.

According to our sources, the demands of the American nuclear reactors could be a major driving force behind the mining projects in Sweden. In the past, the United States has grown reliant on Russia for enriched uranium. The sanctions changed that, at least partly.

According to International Energy Agency data, the global yearly demand for critical metals and minerals should rise 7.5 million tonnes by 2040, jumping to a total of 28 million tonnes. In case of reaching neutral emissions, the IEA estimates the demand to be 43 million tonnes.

Over the past decade, the European Union imported most of its critical metals and minerals from China. China holds a great deal of control over global supply chains – especially when it comes to lithium, the key component of the lithium-ion battery. The EU has thus placed itself into a markedly subordinate position, at least indirectly endangering several of its ambitious sustainability goals.

An increased interest in mining everything under the sun has also been demonstrated in Greenland, where the melting ice hides enormous quantities of natural riches, including uranium. As things stand, uranium mining is not permitted in Greenland, but nothing is yet final. The local authorities are finding it difficult to fend off ever more aggressive suitors. With China on one side and the United States on the other, the Arctic front is now firmly in place.

“Rosatom is a key player in the nuclear fuel business and sells goods and services to Europe and the United States,” says James Action from the Carnegie Energy Institute. »Ironically, the process of weaning itself off Russian fossil fuels has left Europe particularly reliant on Russian nuclear exports.«

Rosatom is also an important factor in the Russian aggression in Ukraine. A former head of the company, Sergey Kyrienko, was one of the special operation’s planners, while Rosatom continues to serve as a large supplier to the Russian army.

Over the last three years, the uranium business once again started to thrive. Uranium prices on global stock exchanges doubled. For example: the worth of a uranium mine located in Canada’s Athabasca Basin has been estimated at 4 billion dollars, even though it will only operate in 2028 when Canada could overtake Kazakhstan as the world’s leading uranium supplier.

Adjusted for inflation, uranium prices were at their highest during the Cold War. After its end, when part of the nuclear weapon stockpile was dismantled, the global markets were hit with a profusion of enriched uranium, greatly reducing the price, sometimes by as much as 90%.

One important yet often neglected fact is that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States began importing large quantities of enriched uranium from Russia and other former Soviet republics. This was possible through the Megatons to Megawatts Program adopted in 1993. Former Russian nuclear warheads were thus used to power US nuclear reactors at least until 2013. 500 tonnes of enriched uranium were shifted under the program, 500 tonnes of which used to make up 20,000 warheads. Up until 2009, the United States paid Russia around nine billion dollars for the said uranium.

The Canadian mining company District Metals entered Sweden in 2020 during the first wave of the pandemic. Until 2022, the world uranium market remained rather static, so at first, the company did not invest much. For the most part, it was content to simply bide its time.

In the wake of the Russian aggression in Ukraine, both the geopolitical and economic situation changed. Given the European dependence on Russian gas and resulting scramble for alternatives, nuclear energy was about to experience a renaissance.

District Metals began exploring new mining options in Scandinavia. “When we saw the situation in Sweden, we started looking for areas where uranium ore could be found,” related the company’s Chief Executive Officer Garreth Ainsworth, a geologist and one of the most recognisable operators in the industry.

Among other ventures, District Metals applied for an exploration and mining permit in the Viken area, where the initial surveys showed the availability of large uranium supplies.

“The permit was cheap, on account of the moratorium. We paid 10,000 dollars for a “mineral license,’”gaining 68 % of the Viken deposit. We later also bought the remaining 32%,” Ainsworth explained. He is firmly convinced that the Swedish government will lift the uranium-mining moratorium by the end of 2025.

“We are certainly prepared for the lifting of the moratorium,” he declared. “When it happens, things are certain to run smoothly, given the Swedish legislature. The process is rather quick. In Sweden, you can get a permit in six weeks. In Canada, the same process takes at least two years.”

The inevitability of the moratorium’s demise becomes even clearer when one considers a report published in December 2024 by the Swedish Ministry of Climate and Enterprise. The report recommended ending the moratorium by the end of the year. Global mining corporations like District Metals are intensely preparing and raring to go.

“The report represents a legislative framework for the lifting of the moratorium. This is not only about mining the uranium but also about processing as well as enriching it,” Garreth Ainsworth explained. Throughout our conversation, the District Metals CEO was highly in praise of Sweden’s mining tradition and infrastructure.

“Sweden is one of Europe’s key mining states,” he enthused. “And not only regarding uranium, but also iron ore, copper, zinc, lead, silver, gold… It is a pleasure working here. The Swedish like to invest in projects in their own country.”

Ainsworth predicted that, after lifting the moratorium, Sweden will quickly build up supply chains – from mining to processing to enrichment to making nuclear fuels. All the way to the end user, i.e. the world’s nuclear reactors. In his vision, the waste, too, would get more efficiently recycled.

“In our unstable times, this is crucial. It has gotten quite chaotic out there. I am sure you are aware that Niger, for example, who supplied the European market with 25% of its uranium ore, is now controlled by the Russians. The CEO of Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom company publicly stated it is now much harder for them to send uranium to the West, given all the pressure from China and Russia,” Ainsworth added.

A strictly political decision

“This is not a green transition; it is a grey one. They are trying to convince us that some of the environment needs to be sacrificed to save the environment. But the solutions they offer are false and dangerous. They always seem to find new excuses to exploit natural resources. Some of these idiots even want to start doing it in Space, all in the name of the green transition!” spat Greenpeace campaigner Carl Schlyter, who represented the Swedish Green Party in the European Parliament from 2004–2014.

“Is there a chance that the corporations might not achieve their objectives?” I inquired. His initial response was a grimace.

“This is not only about the moratorium,” he explained. “Right after Christmas – when everyone was already on holiday – our government proposed the banishment of local community veto rights. The said rights could certainly thwart their plans. But this does not mean the government will succeed. Many of the local mayors are opposed to lifting the moratorium, since they realise what damage could be caused to the environment.”

Schlyter believes that the reasons behind ending the moratorium are strictly political. “In Sweden, the nuclear question is a matter of political prestige. You have to realise that during the last election campaign, the governing parties heavily emphasised the bolstering of our country’s nuclear capacities.”

In 2022, the conditions of the energy markets were very different from today. Fast solutions were the order of the day. “When Russia attacked Ukraine, the prices of earth gas skyrocketed,” Schlyter recalled.

“And the price of electricity also shot up, mostly due to the high price of gas. In Sweden, we were used to exceptionally low electricity prices – the second lowest in all of the European Union! And we mostly got it from renewable and nuclear sources, despite our having shut down a number of nuclear reactors. But when things changed, our industry, dependent on non-carbon energy, experienced a shock. At least for a short while, it was bereft of its competitiveness.”

Expanding Sweden’s nuclear capacities was the key campaign promise and one of the first pledges made by the new right-wing government. A stance Schlyter views as a case study in dogmatism.

“They sold us the idea that the energy crisis will be solved by building 10 new nuclear reactors. But that is absurd!” the Swedish Greenpeace representative was clear.

“In Western Europe, the construction of one such reactor takes 19 years on average, and costs around 20 billion dollars. At the same time, one has to realise that electricity prices have gone down over the past two years.”

This means, he continued, “that 2024 did not see a single month when the price was higher than the ensured maximum price that has been in force for the past 40 years! Yet the government still intends to allocate 35 billion euros in subventions for the construction of the reactors, as well as 55 billion cheap loans. This is not about economics; this is about pure politics. The next election will take place in 2026, and the ruling coalition desperately wants to start building something before that so they can boast of fulfilling their promises.”

Schlyter is almost amused at the neoliberal government adopting a rather communist-dictatorship approach to building new nuclear reactors.

“All over the world, the uranium business is controlled by states and governments,” he explained. “There is currently only one private company dealing in uranium enrichment. It is situated in the US and is not doing very well. The world’s governments dictate the prices and control the market. Even the French are now enriching less uranium – their demand is not that high.”

“So far, there has been very little investment. Our government claims that the recent geopolitical developments are driving up the demand for uranium and that the trend will only heighten in the future. At the same time, the official estimates of the cost of the new reactors are too low by half. The government also promised we will not do business with Russia. But sooner or later, there will be peace with Russia, right? And then our shiny new reactors could easily go bankrupt since they would be producing entirely superfluous quantities of uranium fuel.”

According to Schlyter, the proposed venture was hare-brained from the beginning. “We have zero uranium-enrichment facilities. We have no ore-processing plants. We can open 100 new uranium mines, but not much will change – Sweden will still be unable to produce its own nuclear fuel!”

His main concern is how greater quantities of public funds get allocated to nuclear energy while renewable sources are undernourished. Just before the new year, for example, the Swedish authorities halted the construction of 13 new wind turbines in the Baltic Sea.

“As far as renewable energy was concerned, we used to be one of the most successful countries in the world,” Schlyter lamented. “But when the government got hell-bent on the nuclear option, a certain vacuum was created – one that could last for the next 20 years!”

Carl Schylter believes that mining history – both in Sweden elsewhere – clearly shows the inevitability of drinking water pollution.

“In Sweden, where there’s uranium, there’s usually also high-quality water,” he cautioned. “The European legislation forbids reducing water quality. This could be the protective element. In a time of climate crisis, water is a key natural resource.”

Like many of the locals in Oviken, the Greenpeace activist sees the pending mining plans as a form of colonialism: “Not for the first time in history, Sweden intends to colonise the lands of its Indigenous people. A part of the ruling elite believes that resistance from the local communities can be broken with a colonial approach. But the local communities are far from helpless. The people here are connected. They work together. They also have their own MPs. Colonialism is most easily fought through an empowered local community.”

The Indigenous Sami community is afraid that uranium mining will come at a heavy price to the traditional lands and lifestyles, and a possibility of the degradation of their natural environment and their health. The Sámi (or Saami) inhabit the region of Sápmi, which embodies the most Northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland, and Northwest Russia mostly rely upon semi-nomadic reindeer herding. In recent years, they have already faced the expansion of the wind turbines through their historical land.

“Uranium mines in the traditional lands of the Sami risk having serious consequences for the Sami culture. A mine not only affects reindeer herding, hunting and fishing, but also the relationship with the land and nature,” says Kerstin Andersson, board member of Amnesty Sápmi (part of Amnesty International Sweden). “For the Saami, the land is not an economic resource. It is a legacy from our ancestors that we have to manage for future generations.

A new form of colonialism

Åsa Gustafsson owns a farm near Oviken, a homestead with 65 cows and calves. She is the fourth generation of her family to work the surrounding 150 hectares of exceptionally fertile soil. Her homestead is located next to Storsjön Lake, which supplies water to Östersund, a well-known winter sports resort. Gustafsson’s farm is entirely dependent on the lake’s water.

“The first representatives of mining companies started coming here with drilling machinery as far back as 30 years ago,” the Swedish farmer related. “Even then, they were looking for uranium – among other things. They did a lot of drilling, including some on our land. But then we were left in peace until April 2023, when we got the letter.”

Showing me around one of the neat stables, Gustafsson’s voice contended with a cacophony of moos. “What scares me the most is the water situation!” she told me. “All of the mining sites are located slightly above the lake, so the pollution will be running downward. All the rivers, brooks, and underground water flow into that lake, as well as over local farmland. Sooner or later, some sort of contamination is guaranteed. We have been given no assurances either by the mining companies or by the state. So, I am certainly not going to sign anything. I will be staying right here.”

The green transition has been usurped and privatised by the nuclear lobby, so that local riches could be handed over to the international mining corporation. Such is the view of Bertil Sivertsson, head of the local farmers’ association. He is also a member of the Christian Democrats – a ruling-coalition party which seems to be in favour of lifting the moratorium on the national level and opposed to it on the local level.

“In Stockholm, they seem to believe no one lives in Jamtland,” Sivertsson ventured. “Apparently we do not exist. That is how it is presented to foreign mining corporations. But the reality is that ours is an area with exceptionally rich history and tradition, though all of that could soon end. If they manage to launch the first mine, Pandora’s box will open, and a domino effect will be inevitable.”

“That’s exactly right!” Åsa Gustafsson interjected. “What we have here is a mounting conflict between food production and rare metals and minerals. Or if you prefer, a war between survival and profit. We are currently saving the planet by destroying it. Environment- and animal-friendly farming should be a part of the green transition, not something to be casually swept aside because of it! We all know that here, it is just that no one wants to listen. But we will keep shouting all the same. We will show them we exist! I hope our protests can really make a change. All the farmers here are on the same side. Though I must say that the ever-present threat of pollution or relocation makes it awfully hard to make even minimal plans for the future.”