Turning Tipping Points Around

Humanity is nearing critical climate thresholds. Scientists say we can still shift the future by accelerating positive tipping points.

Climatologist James Hansen recently told REVOLVE that “the 1.5 degree limit has long been dead.” His assessment is blunt. “We are going to hit two degrees within the next couple of decades,” he explained. “That target will be exceeded without purposeful actions to affect the planet’s energy balance.”

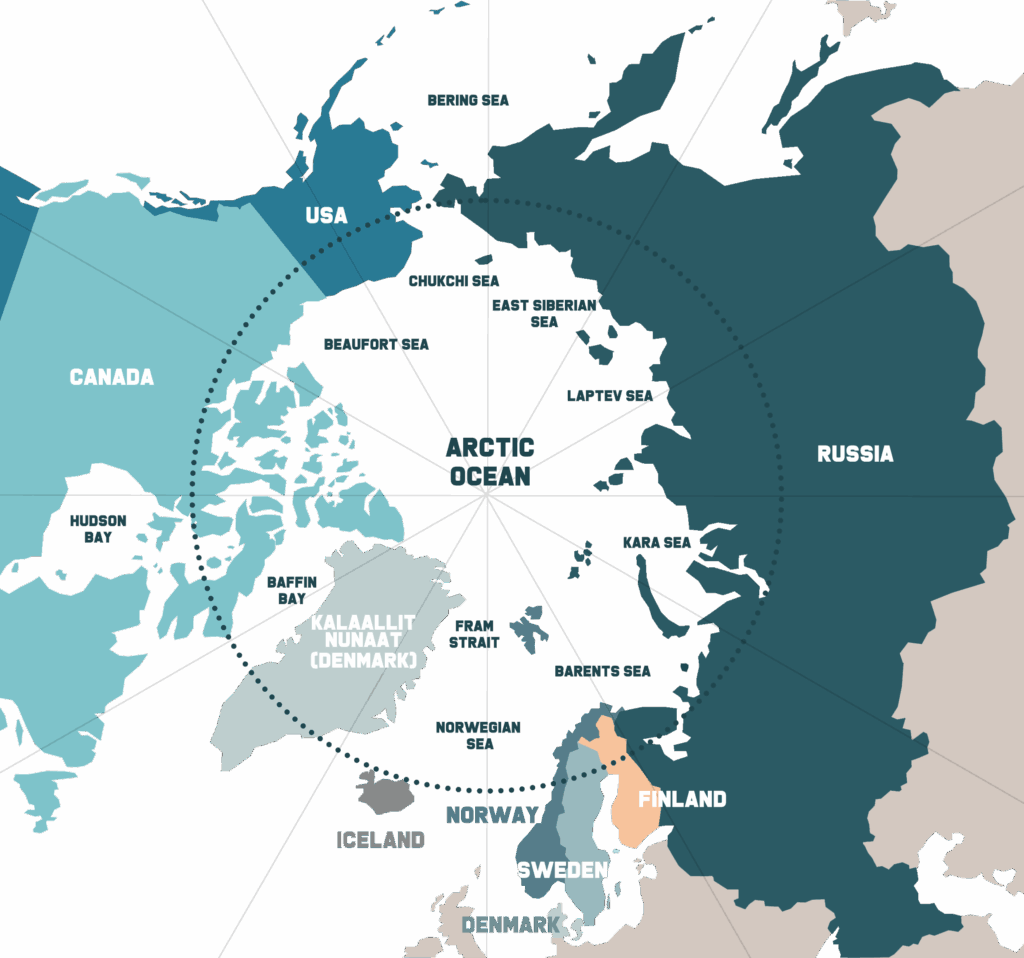

The scientific picture he describes is already visible across several major Earth systems. Oceans illustrate the scale of this threat: they absorb more than 90% of the excess heat generated by global warming and capture roughly a quarter of human emissions. As they warm, marine ecosystems lose resilience, and coral reefs have already crossed thermal tipping points, bleaching at a scale from which recovery is unlikely without rapid cooling, putting global coral extent at risk of falling below 10% this century. In the far north, the Greenlandic Ice Sheet is melting at an accelerating pace, contributing directly to long-term sea level rise. Across the Atlantic, researchers are observing weakening trends in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the ocean circulation system that helps regulate Europe’s climate. And in South America, the Amazon rainforest is showing signs of approaching large-scale dieback due to the combined effects of rising temperatures, drought, and deforestation. Brazilian journalist Daniel Nardin told REVOLVE’s Everything Is Changing podcast that the Amazon faces devastating wildfires year after year, with increasingly severe impacts driven by climate change.

Even if humanity manages to limit global warming increase to one degree, there is still a risk of triggering multiple Earth system tipping points. These changes are not happening gradually. Once crossed, thresholds lead to self-perpetuating and often irreversible transformations. Put simply, a tipping point moves a system from point A to point B in a way that cannot easily be reversed.

Hansen notes that the Earth’s history shows how quickly change can happen. “During the last interglacial, sea level rose several meters in less than one hundred years,” he said. “That implies the West Antarctic Ice Sheet became unstable.”

On a timescale of 50 to 150 years, Hansen warns that “we could get multimetre sea level rise.” In his view, this would be the most severe long-term consequence of continued warming. “More than half of the world’s large cities are on coastlines. That is the disaster we cannot allow to happen.”

The systems at risk

Scientists warn that several major Earth systems are already nearing their limits, and each of them interacts with the others in ways that increase the risk of cascading disruptions. Coral reefs are among the most vulnerable. Long considered one of the planet’s most sensitive indicators of warming, they now appear to have crossed their thermal tipping point. “We are now at the tipping point for coral reefs,” Manjana Milkoreit tells REVOLVE. Reefs provide food, income, cultural value, and storm protection for hundreds of millions of people, and once they collapse, they cannot regenerate under current temperatures.

In the far north, the Greenlandic Ice Sheet and the vast ice shelves of West Antarctica are losing mass at accelerating rates. Hansen stresses that while the situation is alarming, it may not yet be irreversible. “If we cool the Southern Ocean, we can potentially reverse ice shelf loss,” he explains. “But we must bring emissions under control. Otherwise, nothing makes sense.” If these ice sheets pass their thresholds, this could trigger metres of sea level rise, affecting coastal cities across every continent.

In the Earth’s tropical belt, the Amazon rainforest is undergoing its own destabilisation. Rising temperatures and increasingly severe droughts interact with deforestation, weakening the forest’s ability to generate its own rainfall. Milkoreit highlights this dual threat. “We need multi-scale prevention strategies,” she says. “We must limit warming globally and limit deforestation locally and nationally.” Without both interventions, the Amazon risks transitioning from rainforest to savanna, releasing vast amounts of stored carbon in the process.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, the vast ocean conveyor belt that brings heat from the tropics to northern Europe, is showing signs of weakening. Models diverge on exactly when a collapse could occur, but many indicate heightened risk as temperatures approach two degrees. Hansen considers an AMOC slowdown a major concern but not the worst-case scenario. “It would be inconvenient for Europeans,” he says, “but the real disaster is sea level rise.”

Governance gaps that prevent action

Although the risks are increasingly well understood, global governance remains ill-equipped to deal with tipping points. “The institutions we have are unlikely, on their own, to prevent tipping points in their current form,” Milkoreit notes. Climate policy today is built around gradual, linear change, yet tipping points introduce abrupt and nonlinear shifts. No global body is responsible for monitoring tipping point risk, and mitigation timelines remain far too slow to avoid overshoot. Geopolitical tensions make coordinated action harder, and human rights considerations are still not fully integrated into climate planning despite the profound social impacts tipping points will trigger.

For Milkoreit, the immediate priority is clear: “Prevention now means minimising the temperature overshoot beyond 1.5 degrees.” Even brief periods above that threshold increase the chance of irreversible change. Avoiding overshoot requires rapid emissions reductions, accelerated deployment of clean technologies and the expansion of negative emissions. But she cautions that the multilateral system alone cannot deliver this. “Attention is being pulled away to other spaces,” she says. “Some actors have withdrawn from climate negotiations and weakened scientific capacities.” Progress, she argues, must also come from other levels of governance. “Regional bodies, sub-national authorities, and civil society can drive change even when global cooperation is limited.”

Human rights frameworks must also evolve. Tipping points threaten fundamental rights to food, water, housing, culture, and security. “Human rights advocates need to incorporate tipping point science into their work,” Milkoreit says. Without this integration, legal, and institutional systems will remain unprepared for the disruptions ahead.

Preparing for the inevitable impacts

Even in the best-case mitigation scenarios, some impacts are now unavoidable. Governments and communities are beginning to plan for a world shaped by tipping points. The United Kingdom, for example, has invested £81 million (€92.6 million) in an early-warning system to track approaching climate thresholds. Coastal cities are expanding adaptation programs to protect vulnerable populations. Fisheries are reforming management practices to prevent ecological collapse. National disaster agencies are planning for more extreme floods, droughts, and storms.

There are also encouraging examples of ecological recovery, showing how targeted action can reverse local tipping dynamics. Belize strengthened conservation policies, secured new financing mechanisms and engaged local communities to restore its barrier reef. The improvements were so significant that UNESCO removed the site from its endangered list within three years. In Kenya, the Kuruwitu Locally Managed Marine Area began as a controversial community experiment, but ultimately led to rebounding fish stocks and tripled household incomes. In addition, in the Philippines, Apo Island’s community-created marine sanctuary reversed a collapsing fishery and became the model for a nationwide network of local marine reserves. These cases show that while global tipping points pose planetary-scale risks, local action can still deliver meaningful results.

Positive tipping points: a new source of hope

Alongside dangerous thresholds, scientists are increasingly focused on the emergence of positive tipping points. These occur when beneficial change becomes self-sustaining, driven by reinforcing feedbacks that accelerate transitions. The Global Tipping Points Report highlights that such dynamics are already visible across the energy, food and mobility systems.

Renewable energy is a clear example. Solar and wind power are expanding exponentially, and solar capacity now doubles roughly every two to three years, and with each doubling, the price of solar PV panels falls by about a quarter. Battery prices have fallen by more than 80% over the past decade, making storage affordable at scale. Electric mobility shows similar momentum. EVs dominate new vehicle sales in Norway and are growing rapidly in China, the EU, and the United States. . For instance, in Vietnam, electric car sales are estimated to have reached nearly 90,000 units in 2024, more than double the previous year and over ten times the level in 2022, despite far lower income levels and a still-developing charging network. Each increase in adoption expands charging infrastructure, lowers costs, and encourages further uptake.

Social norms are also shifting. More consumers are adopting sustainable diets. A global plant-based retail sales reached $28.6 billion (€24.4 billion) in 2024, with U.S. sales alone doubling since 2017. The global regenerative agriculture market is projected to grow at over 14% annually through 2030 as it spreads across continents. Moreover, active mobility is becoming more common in cities as cycling rates are on the rise. Finally, climate litigation is rising globally, as more than 226 new climate lawsuits were initiated just in 2024, creating legal pressure for faster action. These changes often begin in small groups and spread through social contagion until they reshape entire markets or policies, research suggests that as little as 25% of a population can be sufficient to trigger a broader social tipping point.

Nature offers its own opportunities for positive tipping. Marine protected areas, Indigenous land stewardship and keystone species restoration can trigger regenerative feedback loops within ecosystems. These interventions strengthen biodiversity, enhance resilience, and support carbon removal, creating pathways to bring temperatures back down after overshoot.

As scientists warn of dangerous thresholds, new forms of climate-positive transformation are emerging in different places, from renewable energy markets to the rapid spread of urban clean mobility, where, as Andrew Winder told REVOLVE, “when fleets go electric, the public tends to follow.”

Accelerating positive tipping points

Governments play a critical role in triggering and amplifying positive transitions. As the Global Tipping Points report indicates, mandates to phase out fossil-fuel technologies, strong renewable energy targets, and reforms that reduce financing costs, especially in the Global South, can shift markets quickly. Policies that protect forests or adjust agricultural subsidies influence land use at scale. Investments in carbon removal, nature restoration and coastal resilience prepare societies for long-term change. In parallel, education and public engagement help normalise climate-positive behaviors.

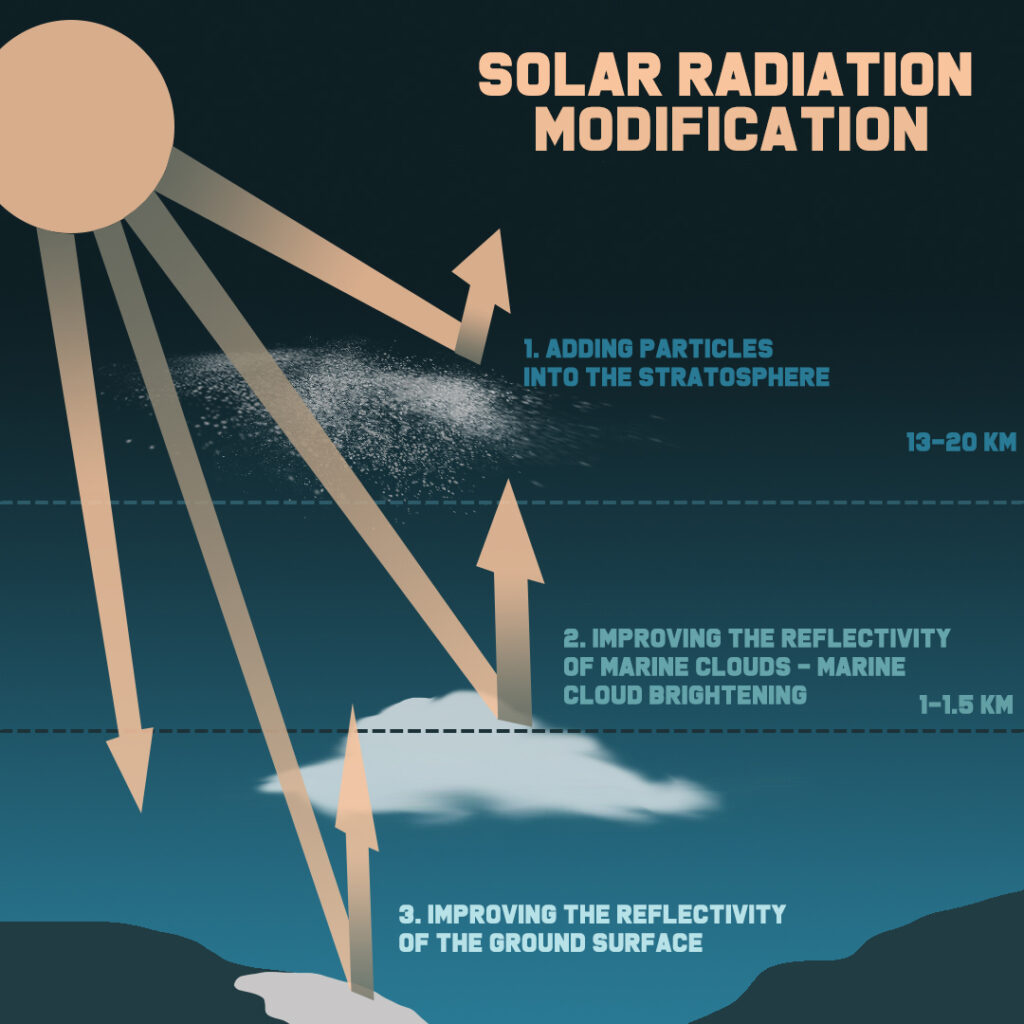

Hansen stresses that the energy transition requires reliable low-carbon baseload power. “Right now, we do not have alternatives for complementing renewable energies which are intermittent,” he says. “It is either fossil fuels or nuclear.” He argues that next-generation nuclear technologies should be developed in partnership with countries that can build rapidly. Hansen also believes that research into climate interventions such as solar radiation management will be necessary. “We will probably need solar radiation management if we want to avoid large sea level rise,” he says. “But we need time to investigate it properly. Still, the highest priority is reducing emissions. Without that, the problem becomes unsolvable.”