The Rainmakers of Morocco

Morocco’s drought-flood chaos fuels a storm of cloud seeding conspiracies.

In the tiny village of Ouneine, nestled high in Morocco’s Middle Atlas Mountains, the sky is everything – a roof, a god, a broker of fortune. For generations, villagers have read the clouds like omens: dark belly, a shifting wind, the scent of damp soil. All signs that rain, finally, might fall.

But in recent years, the sky has kept its secrets. The rain has grown unpredictable, teasing in October, vanishing in March, then returning in furious torrents that carve ravines through parched earth.

In early September 2024, after a week of bone-dry sun, a rain not seen in years swept through the Atlas Mountains, which separate the Sahara from the sea.

“This isn’t natural,” whispered Hassan, a local taxi driver on a narrow mountain road leading to Marrakech. His passengers, a group of villagers huddled in the backseat, nodded or prayed for forgiveness. “They say they’re playing with the clouds now. Trying to make rain, instead of leaving it to God,” he added.

In Morocco, rain is never just rain; it is a divine mood made manifest, a conversation between the heavens and the people. In the past years, whenever winter came dry, King Mohammed VI, Amir al-Mu’minin, Commander of the Faithful, summoned prayer. Salat al-Istisqa, the prayer for rain, is a ritual pulled from the heart of prophetic tradition.

Worshippers, often barefoot, gather in open fields or mosque courtyards, their garments loose, praying for forgiveness and good fortune. In rural areas, sometimes entire villages march together at dawn, with children leading the way, a reminder that innocence might draw divine mercy.

Elsewhere, in the rugged Amazigh communities of the Atlas, girls still perform Taghanja, an ancient rain rite older than Islam.

“Rain is not just weather for us. It is baraka (a blessing). It comes when the earth is ready and the people are humble,” Aicha, an elder from a valley near Ouarzazate, told AMWAJ.

It was in that village that I first began to understand what cloud seeding and clouds themselves mean to those communities. The Amazigh New Year, after all, begins with the agricultural calendar. Here, rain is not just water from the sky; it is a sign, a covenant.

But layered over this spiritual connection is a gnawing mistrust, one shaped not by weather patterns, but by politics. In these remote mountain areas, government officials are seen not as civil servants but as distant figures from Rabat – “Rabat’s people,” they call them. Their promises here feel as intangible as the clouds themselves.

Morocco’s long struggles with drought, and now floods

Morocco has been gripped by its worst drought in decades. For six consecutive years, the kingdom’s skies have offered little more than dust. Rainfall fell below seasonal averages by as much as 67%. The great reservoirs of Bin el Ouidane and Al Massira shrank to cracked basins, exposing old stones and sun-bleached fish skeletons. By 2023, the country’s dam-filling rate dipped below 30%, and in some southern provinces, water had to be trucked in weekly, sometimes daily.

Entire communities found themselves rationed. Taps in cities like Marrakech and Agadir ran dry by early evening, and showers were timed. In Casablanca, the Ministry of Equipment and Water imposed night-time water cuts and instructed traditional Hammams to close three days per week, citing “exceptional scarcity.”

In villages without plumbing, women and girls rose at dawn to walk kilometres to communal wells, only to return with plastic jugs half-filled with brackish water.

The impact on agriculture, the backbone of rural life in Morocco, was devastating. Wheat harvests withered. Olive yields shrank by half, turning olive oil, once a staple in the country’s households, into a luxury only a few can afford. In the saffron-growing belt near Taliouine, the precious crocus flowers emerged weeks late and in sparse numbers. Nomadic herders in the High Atlas have lost entire flocks amid the climate crisis. “There’s nothing to feed them. We’ve sold them or watched them die,” said one Amazigh shepherd near Errachidia.

In Zagora, an oasis town carved into the dusty plains where the Draa River once flowed freely, life has always orbited around the date palm. Water comes from deep wells and traditional khettaras, underground channels dug centuries ago to catch and guide each drop to crops and homes. But in recent years, the wells have started to run dry. Locals speak of sand creeping into their fields, of trees fruiting late or not at all. The river, once a lifeline, now appears only after rare rains, cutting a pale scar through the valley.

The government’s 2022 emergency drought plan offered subsidies to farmers and built new desalination plants. But for many, the help came too late, or not at all. “We suffered a lot the last few years. The drought hit us hard,” said Abrani, a farmer in Zagora.

Then came the rain of September 2024 and again in February 2025. Not a gentle drizzle but a sky-splitting deluge that turned dry beds into torrents and alleys into rivers. The town’s fragile infrastructure buckled under the weight of water that it was no longer built to receive.

“The rain didn’t help the farmers much; it has made the locals’ lives harder. Streets have flooded but, the oasis hasn’t got any better,” added the farmer.

In the arid southern regions of Drâa-Tafilalet, Tiznit, and Zagora, rivers reappeared where dry river valleys (wadis) had ruled for years. Zagora, where annual rainfall rarely breached double digits, received over 200 millimetres in two days, more than it often sees in a year.

In Tata, a desert oasis town on the fringe of the Sahara, floodwaters tore through palm groves and earthen homes. At least 56 houses collapsed, according to the interior ministry, and a bus carrying 29 villagers had vanished into the torrent, leaving at least 18 dead, officials said.

“We have never witnessed anything like this,” said Aberahman, a displaced resident from Tata. In the surrounding oasis, around 90% of the date palms lay twisted, uprooted, ruined. As the waters rose, so too did a strange chorus of conspiracy theories. In cafés, in WhatsApp groups, on Facebook threads, and on YouTube channels, the same theory took root: Morocco had made it rain. The notion isn’t entirely new.

Cloud seeding’s conspiracies and politics

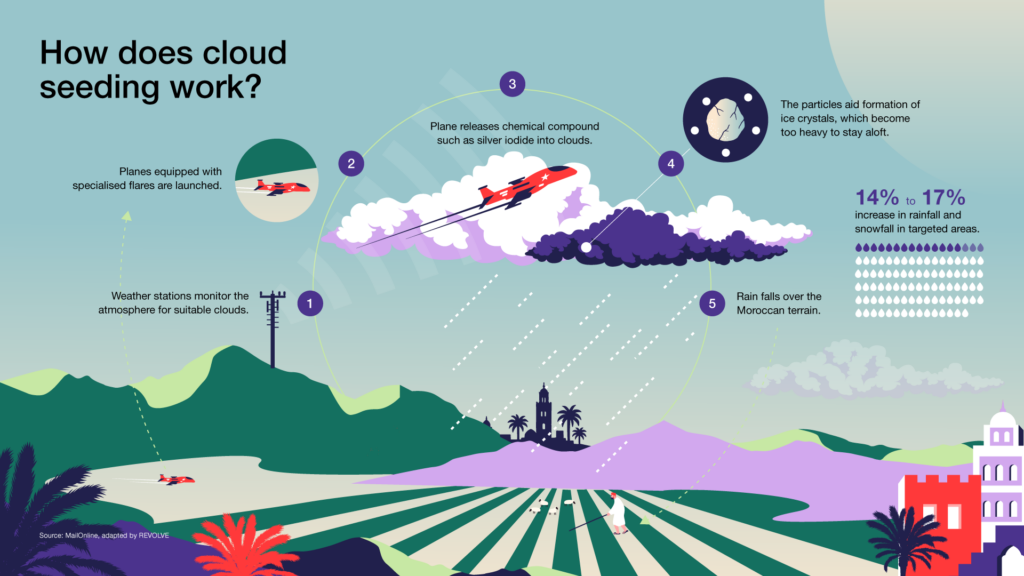

Cloud seeding involves coaxing moisture from existing clouds. Cloud seeding does not create clouds, nor does it conjure weather out of thin air.

“Oh, it would be great if we could make that much rain,” said Mohamed Jadli, a Moroccan climate expert. “That would solve many problems.”

Simply put, precipitation occurs when water droplets and ice crystals in the clouds, which condense around tiny particles of dust or salt, become too heavy to stay afloat and fall back to Earth with gravity. Cloud seeding artificially stimulates this process by introducing substances – typically silver iodide – dispersed from airplanes or ground generators into the clouds that simulate the natural process. When it works, the seeded cloud yields a little more rain than it might have otherwise. When it doesn’t, the cloud moves on.

Morocco has been seeding clouds for decades. Between 1984 and 1989, the country partnered with the United States on Programme Al Ghaith, a $12 million initiative aimed at boosting water resources. The project equipped Morocco with its first weather radar, trained over a hundred specialists, and tested both airborne and ground-based cloud seeding techniques.

Since 2021, with drought intensifying, Morocco has expanded efforts. The government launched 140 artificial rain operations – 52 airborne, 88 from the ground – and shared results publicly.

But as floods swept parts of the country in 2024 and 2025, public suspicion grew. Now, cloud seeding has become the latest subject of speculation on YouTube and in social media circles, where it is portrayed as a covert instrument of influence.

In response, Minister of Equipment and Water Nizar Baraka assured the public that no cloud seeding was conducted in the flood-hit southern regions.

The programme, he emphasised, is scientifically guided, activated only during drought and strictly aligned with meteorological data. In March 2025, after another bout of heavy rainfall, I met Dr. Abderrahim Moujane, a meteorologist with Morocco’s General Directorate of Meteorology.

“No, definitely, cloud seeding had nothing to do with the recent rain,” he said, with the air of someone who has fielded this question many times. “We don’t seed when there’s already rain in the forecast.”

Moujane couldn’t recall the date of the last Al Ghaith operation but was adamant that none had taken place around the time of the floods.

That position was echoed by Omar Baddour, head of climate monitoring and policy services at the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The flooding, he confirmed, took place in areas not targeted by cloud seeding and during a period outside the usual operational window.

Still, between official statements and online rumours lies a gulf of uncertainty. Farmers like Abrani, in the arid plains of Zagora, are left to make sense of rains that come too hard, too fast, and droughts that refuse to end.

“So far, despite the recent rain, we’re still struggling with drought,” said the farmer. “We don’t really know what this rain is. But we aren’t against technology if it’s efficient and it will help.”

“We don’t really know what this rain is. But we aren’t against technology if it’s efficient and it will help.”

– Abrani, Farmer.

Cloud seeding: a solution or a problem for Morocco’s weather chaos?

I sought more answers at the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University. There, I met Perez Kemeni, a researcher at the International Institute of Water Research (IWRI), a newly established research desk in the university. Kemeni spent three years meeting with farmers, listening to their issues, and engaging in debates with them about agricultural policy.

“What we need is not just more technology – it’s communication. Because right now, the farmers are the ones living with the consequences of both droughts and floods,” he told AMWAJ.

What we need is not just more technology – it’s communication.

– Perez Kemeni, Researcher, International Institute of Water Research

The most urgent threat to Morocco’s water resources is the erratic rhythm of climate change: the unpredictable tempo of rain, rising heat, and strain it places on the country’s fragile hydrology. Drought in Morocco is not simply a matter of dry skies; it’s a cascading chain of climate consequences.

Higher temperatures lead to lower rainfall and faster melting of snowpack in the Atlas Mountains – the natural reservoirs that quietly feed Morocco’s rivers and dams – overwhelming reservoirs briefly before vanishing, leaving dry fields in their wake. This flash of abundance is misleading. Farmers may celebrate after a heavy rain, but that celebration is often short-lived.

Mostafa Salah Benramel, an environmental expert and head of Manarat ecology, an NGO that works with local farmers, elaborated further: “These rains won’t help the farmers much because they came late and inconsistently. Crops require consistency, not intensity.”

These rains won’t help the farmers much because they came late and inconsistently. Crops require consistency, not intensity.

– Mostafa Salagh Benramel, Head of Manarat Ecology NGO

A wheat plant, for example, needs water during key stages of its growth. Miss the flowering period, and the plant fails to produce grain, regardless of how much water came before or after. Without a steady, predictable supply, the crop’s life cycle collapses.

“The real crisis isn’t that rain never comes. It’s that it no longer comes when needed, and when it does, it often arrives in violent bursts,” explains Kemeni.

Across the Mediterranean and into Morocco, rainfall is becoming more erratic, and more extreme. A single deluge can trigger devastating floods, wash away topsoil, and drown delicate seedlings, followed by weeks of drought.

In late 2024, severe flooding hit Tunisia, Algeria, and Spain, laying bare the region’s deepening vulnerability to climate shocks.

Morocco’s clay-heavy soils, while excellent at holding moisture, are poorly suited to these extremes. They flood easily and crack dry just as fast. Hydrologists reported spikes in reservoir levels during the storms, but the gains were fleeting. A brief overflow is little match for a month-long drought.

For Kemeni, cloud seeding is promising in theory, yet in practice, it is riddled with complications. An unexpected downpour in a region with shallow reservoirs or neglected riverbeds can do more damage than good.

Rural farmers need timely, clear information on when and where artificial rain might fall. Most Moroccan farmers depend entirely on rainfall for irrigation. If rainfall patterns shift and no one warns them, either through early warning systems or agricultural extension networks, then even the best-intentioned efforts fail.

“Worse, they can become wasteful. Cloud seeding is expensive,” added Kemeni, smiling as he weighed his words.

“If it fails to deliver benefits to those who need it most, the cost is not only financial – it is existential.”

For the young researcher, who acknowledges his limited knowledge of the technology, there is a more unsettling question: how much control does cloud seeding really offer? If clouds can be triggered to release rain, can we determine how much falls, or where it lands?

“If not, the country risks solving one crisis by unleashing another,” he said. “Floods can destroy entire harvests. And after that, few farmers can afford to replant. Seeds are expensive. Insurance is rare.”

In Morocco, the question is no longer whether it will rain – but how, when, and at what cost.

Ancestral practices or technology?

Moroccan meteorological authorities, as well as the WMO, maintain that cloud seeding is used only when strictly necessary. While the Al Ghaith programme reportedly doesn’t directly consult with farmers, it includes climate specialists familiar with the rhythms of the land.

Dr. Abderrahim Moujane, a leading forecaster with Morocco’s General Directorate of Meteorology, insists the floods were a result of failing infrastructure, not cloud seeding. The technology, he added, has helped the country withstand prolonged droughts.

Omar Baddour, a senior climate official at the World Meteorological Organisation, estimates that cloud seeding can, at best, increase rainfall by 15%, if conditions are favourable. “That is not enough,” he said.

Even globally, faith in cloud seeding is waning. Australia scaled back in the 2000s after inconclusive results, the U.S. limits its use to a few mountainous states, and Senegal, once a partner of Morocco, withdrew due to inconsistent outcomeswithdrew due to inconsistent outcomes and changing climate patterns.

In parallel, Morocco is scaling up desalination projects, particularly around Casablanca and Agadir. But local groups warn these are stopgap measures.

“At the heart of Morocco’s water crisis is a model of agricultural development that has prioritised exports over resilience,” says Abdeljalil Takhim of Nechfate (a Darija word meaning “it dried.”), a local platform focused on raising awareness of climate change issues.

Since the early 2000s, state policy has shifted towards liberalisation, championing high-value crops such as tomatoes and berries for European markets. The 2008 Green Morocco Plan deepened this focus, investing in drip irrigation and genetically improved seeds to boost yields and foreign currency.

But this model has marginalised rain-fed agriculture – the backbone of subsistence farming in Morocco’s mountains and oases. Cereal crops and other staples, once central to food security, have been dismissed as low value.

“Government subsidies have mostly benefited large agribusinesses, enabling water-intensive practices while leaving smallholder farmers behind,” Takhim said. “And much of the subsidised produce isn’t even consumed locally– it’s shipped to European grocery stores.”

The profits rarely reach the rural communities whose wells are running dry.

What Morocco needs now, Nechfate argued, is a philosophical shift: away from export-oriented agribusiness and toward agroecology and sustainable, locally rooted practices rooted in the knowledge of those who have cultivated these lands for generations.

“Traditional water-sharing systems, drought-resistant crops, smallholder farms, these carry not just genetic diversity, but a legacy of resilience,” Takhim said.

In a country where rainfall is both omen and algorithm, the future may depend on an uneasy partnership: Rabat’s satellites, silent and precise, scanning the upper air; and the mountain farmers, reading the clouds as their ancestors once did.

Between them lies not just distance, but a different way of knowing. Yet for environmental experts, only in that fragile space, Morocco may find its way out of its climate crisis, not by controlling the sky, but by learning to coexist with its caprice.

This article was produced as part of the AMWAJ Media Fellowship. The full article was published first as part of AMWAJ’s Tayyarat story series.