Missing the ‘F’ in Sustainable Mobility!

We all agree that we need to shift transport away from fossil fuels to low-carbon, sustainable mobility. However, the trends for more and better transport are not delivering increased prosperity for all…

One of the major challenges that policy-makers face today is reconciling the need for growth with environmental protection and social development. Transport is both an enabler and a barrier to this as each transport sub-sector or thematic area has different, and frequently conflicting priorities, especially within and between public and private institutions and departments. Transport is particularly complex with the many dependencies between mobility and access, the need for goods and people to travel and other key development areas such as education, health, economic growth and societal stability. In the past, high-quality transport system was seen as a prerequisite for development and a higher quality of life. However, now there are many signposts indicating not only that we need shift our transport away from fossil fuels to low carbon, sustainable mobility concepts, but how we should be doing this.

Sustainable mobility takes many forms, but its underlying premise is that carbon intensity of transport and travel is reduced compared to today while accessibility and connectivity (both physical and virtual) are at least maintained, and in some cases, increased. A major reorganization of people’s life-styles and business practises is needed, and a lot of attention is being given to electric mobility and other technical solutions. Politicians are anxiously putting programs in place to boost electric mobility as a major part of the solution. Attractive, shiny, all electric cars are becoming almost affordable and salesmen (and women) boast of “ranges of four to five hundred kilometers’ with glints in their eyes as they ‘steal your money’ for these highly-priced vehicles.

There is real value in increasing the number of women in all sectors that are strongly male-dominated.

In the past, speed and travel time savings were cornerstones of transport design, planning and investment. But we now realize that a trend of more and better transport does not deliver increased prosperity for all – in fact it creates divides between the ‘have all, the have less and the have nots’. Yet it is still difficult to move policy away from tinkering at the margins to make electric cars more affordable, promote car- and bike-sharing and building high-speed rail that take us further quicker. Although it is certainly true e-mobility will play a major role in the future, but this will come at a high cost and it seems that many lower-cost options are being neglected.

The majority of people dislike change – and looking more closely at what and who is going to have to change as well as the risks if we get it wrong shows there is much to fear. Those in positions of power and most decision-makers are more than comfortable with making a few small changes, rather than getting down to some of the central problems with the sector. One of these is bringing in the ‘F’ word and bringing in the ‘F’ power into the sector. I am, of course, talking about feminizing the sector! Personally, I fear that without this the sector will neither become sustainable nor as low carbon as is needed within the time frame we have to make change.

Thankfully, there has been a seismic shift in thinking about diversity and equity. Indeed, this is reflected in the international agenda with gender-based targets set out the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the New Urban Agenda giving a clear framework for governments to follow. In addition, there is a growing consciousness that there is real value in increasing the number of women in all sectors that are strongly male-dominated.

The construction and transport industries are prime examples of where change needs to happen, as neither can boast about their gender balance especially at decision-making levels and the composition of the workforce. This may be not surprising as historically women were excluded from many of the technical degrees and many jobs were not suitable for women as they typically required both ‘brains and brawn’, but this is no longer the case and it is time to open the doors and get more women involved.

Although, it is quite legitimate to ask why it is important to bring in more women into transport there are a number of very good reasons that are stacking up. Firstly, we need to get more women working in all sectors of the economy. This would be good for global growth. A report by the McKinsey Institute (2015) suggests that women account for 37% of measured global GDP, but that fully eradicating gender gaps could add up to 26% to global GDP relative to a ‘business-as-usual scenario’. The OECD has similar projections stating that closing gaps between men and women could add 12% to OECD countries’ GDP by 2030.

As women make up around 50% of the adult population, they present an untapped resource. Getting more of them earning would also help address poverty issues as currently, there are more women in precarious informal jobs, unemployed or simply unable to work outside the home for money.

Women are the majority of users of public transport in both developed and developing countries… because they have to not because they chose to.

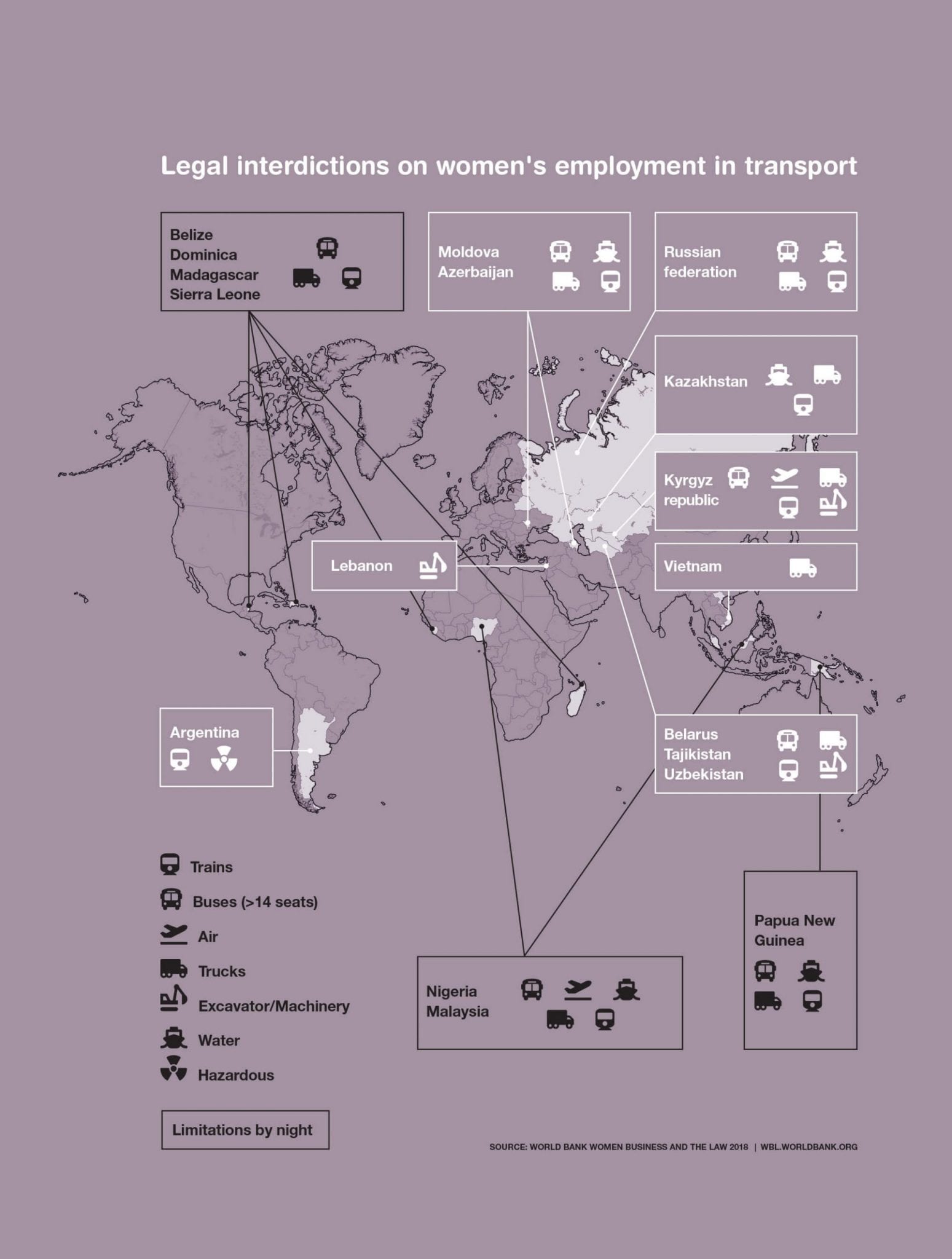

Transport offers many opportunities for employment, but most jobs are still considered to be ‘men only’. According to the 2018 Women, Business and the Law report, 19 economies impose restrictions on women’s employment in transport. Overall, as many as 104 countries have at least one legal restriction on women’s employment in general (including transport). Examples include restrictions on night-time work, driving trains or heavy-duty vehicles.

Numerous barriers exist, most notably about issues around recruitment bias, where men are still preferred against taking on an equally qualified woman; and globally, there is a major gender pay gap. In most countries, women earn on average only 60-75% of men’s wages.

On the other hand, there are numerous risks that we should be aware of if we do not change the current transport paradigm. Women are the majority of users of public transport in both developed and developing countries. This comes as no surprise when we consider the different mobility patterns between men and women. Women tend to make more frequent, shorter trips, while men typically make longer single destination trips. In the developed world this is beginning to change as roles become reversed and men more actively share family responsibilities. However, this is not yet the case in much of the developing world, where women are still responsible for most of the caring duties associated with family life.

Despite being high public transport users, most urban networks are not designed with their needs in mind and the majority of improvements are based on travel time reductions, which in turn is linked to speed rather than connectivity. Women walk and take public transport more than men – but this is because they have to rather than they chose to. In research by the FIA Foundation and CAF, they found that even low income women would shift from these habits very quickly if they are given the opportunity. That opportunity will come as they become more empowered and financially secure. Indeed, this is already starting. Trends in the US and some European countries show that there are more women than men applying for driving licences, registering private cars and applying for car insurance.

Unfortunately, women are often targeted for harassment and hate crimes while using public transport or when they use public space to access it. Verbal or visual harassment is most common everywhere, but it sometimes leads to rape or death. The #MeToo Movement has one simple aim: Make the world safer for women by ensuring women are free from sexual harassment, abuse, assault, and rape. This goal relates as much to transport as other sectors. An 18-year-old black woman was killed while travelling late one evening on the San Francisco subway at the station where she got out. So, it is not surprising that the majority of women are concerned about their personal security based on their own experience or that of their close family or friends. Many learn from their mothers at an early age that public transport is unsafe, inconvenient and crowded. Indeed, safety and security concerns greatly affect women’s mobility.

Transport plays a huge role in ordinary women’s and girl’s lives by getting them into work and giving them access to education that will in turn give them more choices when they are adult. The converse is also true – and if they perceive it not to be safe, secure and affordable, they will simply not take up the opportunities presented to them.

Women account for 37% of measured global GDP

(McKinsey Institute, 2015)

Women are becoming more vocal in expressing their transport needs. Women’s voices shouted loud and clear in London when the international Ride Hail service Uber was mooted to be banned – these services were more attractive and useful to them than regular public transport and taxis. In a study in 6 cities by the World Bank, comparing such services in cities as far apart as New York and Jakarta, they found that women like to drive as it provides a flexible option for work, it provides affordable door-to-door services and it appears to be no more or less safe than other taxi-type services.

When we look at who are the decision-making roles for transport, it remains overwhelmingly male. There are a few outstanding examples, of course. One being the present European Commissioner for Transport, Violeta Bulc. Looking at around 60 OECD countries, a review of Ministers of Transport revealed that only 9 were female (July 2018) or around 15% of the total including Chile, Estonia, Finland, France, Korea, Netherlands, Serbia, Switzerland and USA. But only one from the Global South. A number of these have been in place for several years while Chile only recently appointed its first female Transport Minister. If we can bring in more women as planners, engineers and project designers, it is more likely that women needs may be better planned into the systems we design and build, and that they may well remain as high users of public transport rather than shift to other modes.

The stakes are high. If women shift from their current low carbon mobility habits to high carbon mobility, we risk making a lot of effort just to ‘stand still’ and technology cannot fill the gap. The sector will not be able to reduce its carbon intensity as an increasing number of women become motorized in their own right (even if they choose slightly smaller and less polluting cars than men do). The risks to sustainable mobility are therefore very real but there is still inertia in the sector to change.

What can cities and national governments do? Luckily there are many reports and policy papers that can provide guidance. GIZ’s Transforming Urban Mobility Initiative (TUMI) have updated their SUTP report on Urban Transport and Gender; the FIA Foundation and CAF have been working on comparing and contrasting women’s personal security in three Latin American cities and have developed the results into a summary and toolkit; and lastly the World Bank are including a gender chapter in their upcoming report for SUM4ALL (Sustainable Mobility for All) initiative. They have clearly identified the areas of ‘women as users, decision-makers and workers’ as thematic focal points and they will add this topic as a chapter in their update of the Global Mobility Report for the first time in early 2019. We can only hope that people are ready to listen and to change at the core of those who make the decisions about transport, and that this comes in time!