Rural Land Ownership

Gender equality in rural land ownership is essential for lasting, meaningful climate action.

In 2015, the United Nations set out a series of objectives in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that aim to improve life for all, both on an environmental and societal level. The Agenda contains 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including SDGs 5 and 13 on gender equality and climate action.

Gender equality and climate change are interlinked. According to the United Nations Secretary General, António Guterres, “Rural women are the first adopters of new agricultural techniques, first responders in crisis and entrepreneurs of green energy” and are a powerful force for driving global progress. However, the impacts of climate change, including access to productive and natural resources, amplify the gender disparities existing in rural areas.

Rural women perform nearly half of the world’s agricultural work. One in three women are employed in the agricultural sector, yet this figure rises to over 40% in developing countries. Women cultivate fields, make agricultural products, and are responsible for taking care of families at home. In many regions, they are also responsible for water collection in areas with no running water, with rural women in Sub-Saharan Africa spending 40 billion hours a year collecting water.

In low- and middle-income countries, persistent gender discrimination and related norms mean that adolescent girls living in poverty are often the most vulnerable to the less visible impacts of climate change. This includes disruptions to their education, increased poverty over time, and an increased risk of early and forced marriages.

This inevitably stunts their economic empowerment and participation in political and public life, as well as access to services, health care, adequate food and nutrition, and to water and sanitation services. The complex articulation of discrimination against rural women makes them too often invisible victims: women produce 50% of the world’s food, but own only 1% of the land.

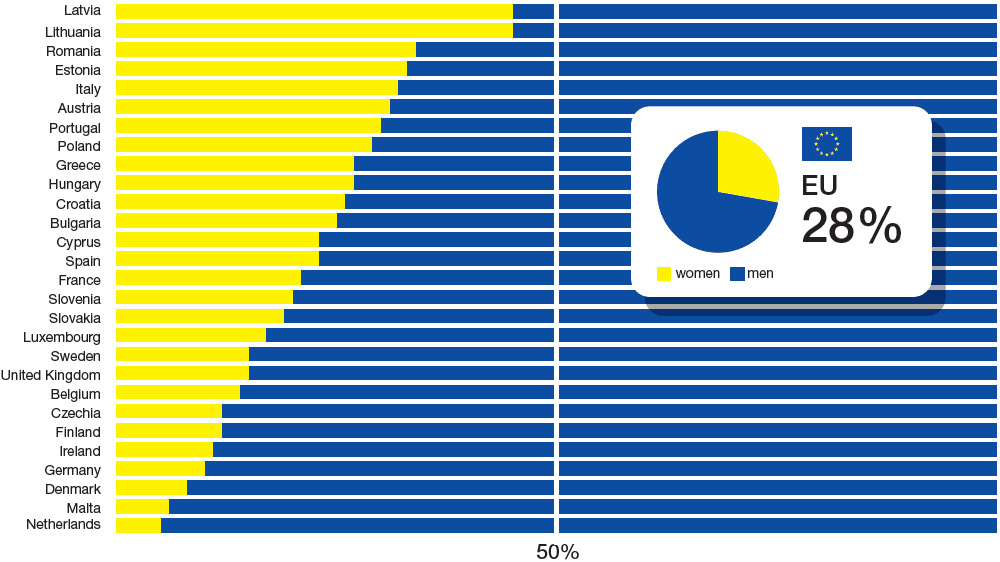

The number of rural women living in poverty has doubled since the 1970s. According to a study by the European Commission, almost half of the rural population in the European Union consists of women, but only 30% of farms are run by women. The differences from country to country are significant: 45% of positions of responsibility are held by women in Latvia and Lithuania, to 10% or less in Germany, Denmark, Malta and the Netherlands. Yet several studies show that women could be able to increase their farm yields from 20% to 30% if they had equal access to resources.

Bigger yields would translate into bigger incomes. This would be a win for the planet as increasing crop yields on existing farmland is an essential part of food security and resource efficiency. By focusing on these areas of inequality in rural communities, it is possible to facilitate the positive social, economic and environmental change needed to tackle global planetary challenges such as climate change.

Agents of change facing climate change

Climate change affects the well-being of women and men in different ways in terms of agricultural production, food security, health, water resources, migration, climate-induced conflicts, and natural disasters. In rural areas, women are often the first to suffer the consequences of damage to natural resources and agriculture. For instance, one-quarter of the total damage and losses undergone between 2006 and 2016 was sustained by the agricultural sector in developing countries, with a significant impact on food security and the productive potential of women and girls.

In developing regions, women and girls are primarily responsible for the supply and use of water, yet these are the areas most susceptible to the adverse effects of climate change. Drought, for example, means an increase in the amount of work for rural communities, for instance, a greater number of hours required to collect water. With women acting as the main suppliers for rural families, these additional responsibilities almost always fall on them. This results in a consequent drop in school attendance amongst girls, with ripple effects from a reduced education restricting their possibilities for future employment or public service.

Yet despite these hardships, there is no doubt of the added value of women to rural communities. According to the FAO, rural women produce about half of the food consumed in the world and are responsible for a variety of related tasks including searching, collecting and processing food – tasks that are vital to areas suffering from food-insecurity. But still the risks of climate change loom over rural women more than men. According to the FAO, because women rely more on natural resources for their livelihood, they are exposed to the climate risks more than men thus absorb greater climate-related shocks while not benefiting from in advancements in climate-smart technologies or practices, which is a key to enhancing sustainable food systems.

This example makes clear the intimate relationship between climate change and gender equality: addressing one issue while neglecting the other will fail to secure a sustainable future for all of those living in these vulnerable areas.

Women taking action

For the harsh realities faced by rural women, there are examples worldwide of rural women fighting for sustainable change. In the Sunderbans mangrove forest in India and Bangladesh, Rita Kamila has been striving for nearly a decade to achieve the right blend of farming and livestock husbandry in an area particularly susceptible to a changing climate.

People living in the Sundarbans region suffer from a water shortage in the dry season as a result of increasing salinity in the groundwater, and of the river Satkhira, caused by rising sea levels.

In recent years, her farm has successfully transitioned to organic, growing a variety of foods using integrated farming concepts to grow livestock and farm fish. A biodigester plant was installed to generate biogas from farm waste such as livestock manure and fish waste. The biogas is then used for cooking and the residues are recycled back as nutrients to crops.

Another example are the farmers from the Medak District in Telangana, India, that are teaching peasants in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region how to use sustainable rain-fed farming techniques. As some of the poorest members of their village communities, these women were once landless laborers, but today, thanks to the women-led, village-level farmer associations, these women have not only tackled their farming problems but are generating an additional income through innovative and eco-friendly ways.

Using traditional preservation techniques, these women preserve organic seeds that they barter with other farmers in the region. Chandramma, who heads the Seed Bank at Pastapur, explained how they pick and keep the healthy grain in a mud container, layered with neem leaves, ash and dry grass. They then seal the whole box with mud, dry it and keep it in a secure space.

On their month-long seed bartering journey to 30 villages in the region, Chandramma and her fellow farmers teach other villagers how to follow organic farming methods and grow climate-resistant crops like traditional varieties of millets. Many of them have also become filmmakers despite no formal training, and have produced documentaries on organic farming, seed sovereignty, biofertilizers and good farming practices that have been screened worldwide and also launched the Sangham community radio, educating farmers in in over 200 villages in the region.

Their rights and struggles concern all of us

These social movements, among others, are part of a long advocacy process that has led to the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants adopted in 2018 by the United Nations. This document is an elaboration on the rights of rural people and also addresses sectors such as artisanal and small-scale agriculture, crop planting, tourism, fishing, forestry, hunting, and also addresses different groups like indigenous and nomadic people, among others.

Article 2 of the Declaration pays particular attention to the rights and special needs of people working in rural areas, recognizing women as a discriminated group, which is an important step to increasing gender equality, but there is still a long way to go.

Rural women are references for the entire rural community and are at the frontline when natural resources and food are threatened by natural and political events. Despite the landmark UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants, rural women are still far from being treated as equals in all aspects of society, and particularly in agriculture.

Giving women access to agricultural resources, training and services could increase the productivity of their farms and feed up to 150 million hungry people around the world. As long as we are not giving proper importance to women and their living conditions, how can a family, or a society, or indeed a country be cultivated for the better?

***

Women are change agents, meaning that if a change is needed they will often be instrumental in identifying what needs to be done and then making it happen. Climate change is a huge and existential threat, but women play a fundamental role in our fight against it. Any problems we face as a result will be easier to solve if both men and women are equally included in solving them. To this aim, the campaign SHE Changes Climate was launched during COP26. Its global mission is to ensure all delegations in climate negotiations have at least a 50% representation of diverse women at their top levels, now and in the future. That is why they have launched a campaign #5050Vision calling for all parties to be represented in decision-making processes – because it affects all parties.