Lampedusa: The Forsaken Island

Without any freshwater resources, Lampedusa needs renewables for sustainable water access.

Lampedusa is Italy’s southern-most island, located off the eastern coast of Tunisia on the longitudinal level of Kairouan – one of the four holiest sites in Islam. With a population of about 6,000 inhabitants, Lampedusa is Catholic and they celebrate their local patron saint of the island (La Madonna di Porta Salvo) on 22 September by walking through the narrow streets in the evening. Coinciding by chance with this festival, REVOLVE was in Lampedusa for a field trip for the WATER-MINING project.

WATER-MINING is an EU-funded project that is developing energy-efficient technologies for treating wastewater from urban areas and industrial sites, while promoting the extraction of valuable resources from the residues generated during the processes. The technologies for extracting minerals and providing freshwater from seawater include nanofiltration, eutectic freeze crystallization (EFC) and desalination. The Lampedusa power station and desalination plant is one of the case studies of this project.

A water-stressed island

Unlike Malta that still has some (rapidly depleting) groundwater aquifer reserves, Lampedusa has no freshwater resources. Entirely devoid of water, the population of this flat rectangular 20 Km2 stone formation protruding from the Mediterranean swells to 30,000-40,000 with the arrival of tourists from Italy and abroad during the summer season; not to mention the unspoken and estimated 25,000-30,000 migrants who are somewhere in camps inland (that we did not see during this trip) that also need fresh water on a daily basis.

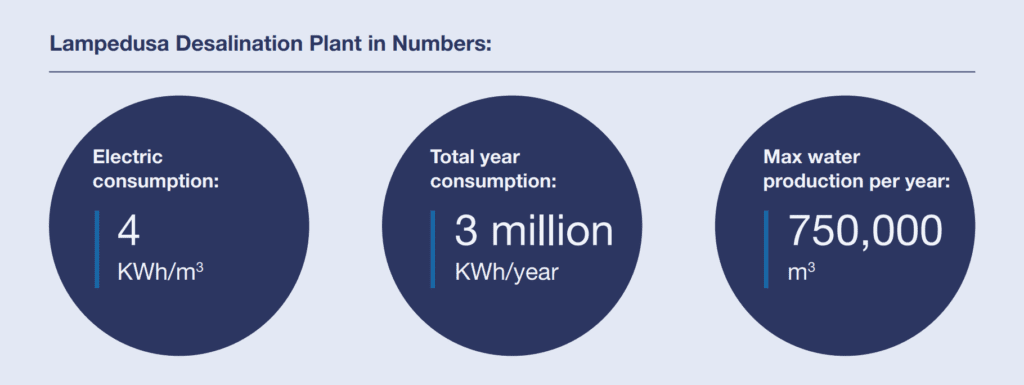

Water scarcity and a complete lack of natural access is not a theory but rather the day-to-day reality in Lampedusa. Tankers bring fresh bottled water by cargo ships that are powered by diesel engines and the desalination plant pumps out 3,500 cubic meters per day (also powered by the diesel power station) of potable water that is sent to one of the seven municipal reservoirs, providing drinking water to the inhabitants and visitors. Water stress obviously accrues severely during the summer tourist season.

The Lampedusa desalination plant was ahead of its time when in 1992 solar photovoltaic (PV) panels were installed to power the energy-intensive reverse osmosis (RO) process of removing salt from seawater. Back then, the PV-RO combination produced about 1,500 cubic meters of fresh water per day, which has since doubled with greater demand and capacity. However, this has not been without local complications with renovation permits and different municipal administrations.

30 years since their installation, the solar panels have fallen into complete disrepair due to petty local politics that have blocked the permit renewal to revamp the PV installations. The private company operating the plant – SELIS – continues to lease the land from the municipality to operate the desalination next to the sea, by the Cala Pisana enclave on the eastern side of Lampedusa, yet they cannot renew the solar panels without municipal approval. While the situation is expected to change with a new municipal administration coming in 2022, the desalination plant remains powered by diesel in the meantime.

According to Angelo Catania, Technical Manager at SELIS for the desalination plant, if the reservoirs of Lampedusa were in proper operation, then it would be possible to have more water than needed during the day with a PV plant (instead of 1,500 m3/day, we could reach 3,000 m3 every 12 hours, or more. This would mean a quadrupling of the capacity of clean water produced). As the reservoirs are on higher ground, the excess water could be stored here and then distributed via the water pipe networks during the night using gravity. In the future, Mr. Catania asserts that this could be possible, if the reservoir systems were to be revamped. By using the natural pull of gravity, instead of having water storage that is powered by batteries, we could have storage powered by water, thus reducing the greenhouse gas emissions from the power station. This would be the most sustainable solution for providing clean water to all the inhabitants (and visitors) of Lampedusa.

Regional water dynamics

Desalination was introduced to Lampedusa in 1972 at a time when there were three desalination plants in Italy, including Trapani, Gela and Porto Empedocle. The land where these desalination plants were located was owned by the regional government, such was the case for the islands of Linosa, Pantelleria and Lampedusa as well. In particular, in minor islands, not all water came from desalination, as much of it still had to be transported and imported. The provision of water more broadly was under the responsibility of the Ministry of Defense that would pay for tankers to deliver water to the islands. This water was essentially free of charge for the municipalities to sell to the inhabitants.

Lampedusa has no natural access to freshwater.

In addition to these complexities and the tensions between regional-municipal ownership, there are the private companies owning the desalination plants (in terms of equipment only), whose role is to ensure that clean and fresh water is being provided via the pipes from the desalination plants. A sobering fact is that regardless of the source of the clean water, there is a very serious infrastructure problem: there is an estimated 30-50% leakage issue in minor islands, meaning that half the water is being lost via cracks and holes in the old pipes. Therefore, it is important to see the bigger picture to understand that the water-energy ecosystem needs to address and resolve integrated water management before increasing investments in more desalination and reclaimed wastewater. The Salva Mare legislation of May 2022 goes in that direction.

“Lampedusa wants to be a flagship frontrunner of the energy transition,” says Angelo Catania. Islands are symbolic of the potential for energy independence in Europe and elsewhere. Getting off fossil fuels is a political game but also a reality in the transition towards integrating and deploying renewables more robustly. Coupled with greater electrification and energy efficiency technologies like heat pumps, renewable energies (solar and wind in particular) can lead the way in providing cleaner water more sustainability for future generations.

In the WATER-MINING test site in Lampedusa, there is already progress in the efficiency of the technologies being tested. In comparison to a previous project, ZERO BRINE, where the EFC unit in Botlek, the Netherlands, produced 10 liters/hour of fresh water, here in Lampedusa the EFC unit has improved the prototype drastically to produce 100 liters/hour. We are talking about the efficiency of producing clean water and using the byproducts of sodium chloride solutions for fertilizers, detergents, the glass industry and even for dyes in the clothing industry.

Making Europe more competitive

These are circular economy actions that are hard to see and understand at first in such small testing sites, but they have tremendous potential for being replicated in urban wastewater and industrial wastewater treatment plants to deliver fresh water, and to create those virtuous cycles of recovering the valuable resources that so often still go to waste. Improvements are also being made in extracting magnesium from industrial and urban wastewater sludge, making Europe more competitive as the global magnesium market is controlled largely by China.

During our visit, the Adviser to the Mayor of Lampedusa for Health, Family and Technological Innovation, Dr. Aldo Di Piazza, claimed that a more “sustainable future is possible”. With greater societal awareness and environmental considerations becoming embedded in such projects as WATER-MINING, he may be right: the potential is there to produce water sustainably with power from renewables and to recuperate the maximum amount of minerals and freshwater, while minimizing the waste being discharged into the sea or into the surrounding landscape, thus contributing to the circular economy in a replicable and scalable way across Europe.

The last Prince of Lampedusa, Guiseppe Tomasi said in his novel The Leopard that things need ‘to change to remain the same’. Now in Lampedusa, things need to change – quickly – to become more sustainable.

The author is grateful to Angelo Catania from SELIS and Andrea Cipollina from the University of Palermo (UNIPA) for their valuable input.