India’s Relationship With Palm Oil

Plans to boost domestic production raise concerns about the risks to biodiversity.

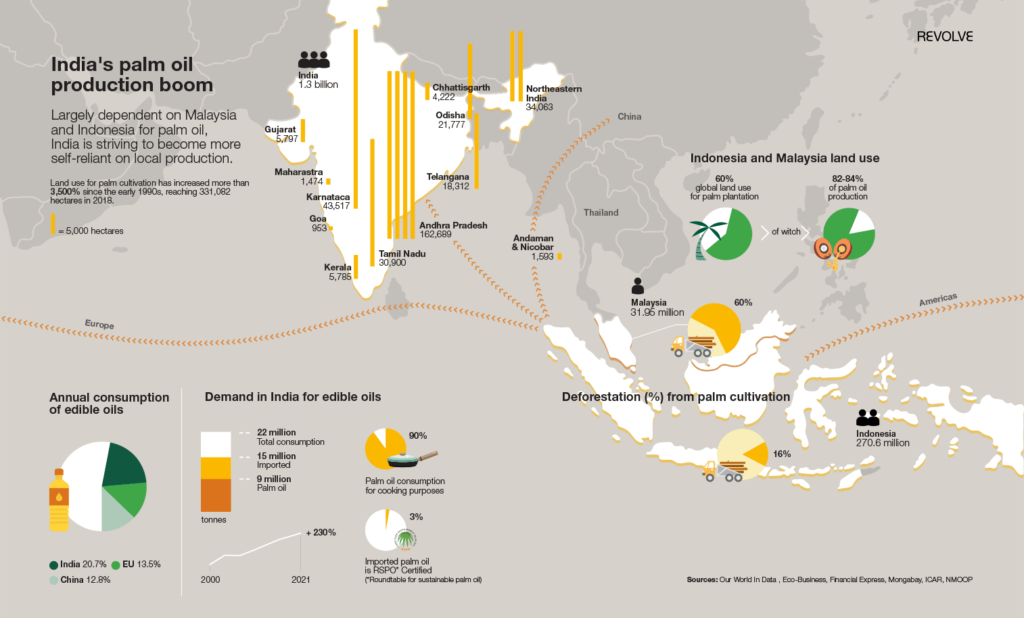

India is one of the largest consumers of palm oil, responsible for using 20% of global supplies, primarily for cooking and food production. Much of the country’s growing demand is met by Malaysia and Indonesia, where mass cultivation of the crop has been linked to deforestation, contributing to India’s so-called ‘imported deforestation’ footprint. In August 2021, the Union Cabinet approved INR 1,100,400 million (€1.2 billion) to be spent through the National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) over the next five years to boost domestic production, raising major concerns about the risks to biodiversity in India.

As defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), imported deforestation occurs with “the importation of goods whose production has contributed, directly or indirectly, to the deforestation or conversion of natural forest ecosystems”. This article gives an overview of the complex nature of the linkages between palm oil production, sustainability, as well as implicated livelihoods and food security in India. The low price of palm oil makes it a more viable and attractive option for a country where 22% of the population lived below the poverty line pre-pandemic, and 75 million more people are with incomes of $2 or less a day, due to the pandemic-related economic downturn, while the Indian middle class is also estimated to have shrunk by 32 million in 2020.

Palm oil is a lifeline not only for the farming population in Malaysia and Indonesia, but also linked closely to the food and livelihood security of consumers (both commercial and domestic) in India. Efforts to reduce Indian import expenditure by increasing domestic production have raised questions around sustainability as well as the feasibility of producing the quantities required to meet demand. The way forward will not be easy, as it must involve a combination of more sustainable manufacturing of palm oil, with potential alternatives that do not increase costs for manufacturers and consumers to safeguard both biodiversity as well as livelihoods. Current solutions are limited – we need better data as well as greater awareness of the issue amongst all stakeholders.

The Livelihoods & Food Security Nexus

India’s population of 1.3 billion and growing, is a large consumer of edible oils, with an annual consumption demand of about 22 million tonnes as of 2020, of which almost 15 million tonnes (68%) was imported and palm oil accounted for 9 million tonnes (60%) of total imports. Palm oil is a preferred choice amongst edible oils because it is one of the cheapest sources of cooking oil, and palm is the highest oil-yielding plant in the world. Almost 90% of the palm oil consumption in India is for cooking and food production, which includes businesses in the informal and formal food sector (small businesses, sweet shops, and local street vendors) as well as households. It is also used as an ingredient in a wide range of consumer goods, like cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, detergents, and biofuels. As a result, the demand for palm oil in India is high, and there has been a 230% increase in consumption in the last two decades alone. Consumer awareness however, on both the imported nature as well as the link between palm oil production and deforestation in other countries, is low.

Malaysia and Indonesia, from where much of India’s palm oil is imported, account for 63% of global land use for palm plantations and 84% of palm oil production. Several arrangements in the past have ensured the trade continues to safeguard livelihoods on both sides of the supply chain. Indonesia for example, relaxed the quality requirements for their sugar imports in 2020 as part of a barter exchange to secure palm oil export access to India and to deal with the dwindling local supply of sugar. As the palm oil sector has matured in Indonesia and Malaysia, they have taken steps toward reducing deforestation: Malaysia has a cap on its land use at 6.5 million hectares and Indonesia has a moratorium in place on the further development of the palm oil sector. To ensure the sustainable manufacturing of palm oil, Malaysia and Indonesia have created mandatory certification schemes – Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO). Yet, direct deforestation caused directly by palm oil is at a staggering 60% in Malaysia and 16% in Indonesia.

Domestic Production of Palm Oil in India

In efforts to reduce its $480 billion (2019) import expenses, India has tried ramping up domestic production by incentivizing farmers to grow palm oil in place of existing crops. The uptake from farmers however has been slow, as growing the palm oil crop comes at a considerable cost. The gestation period is long: around 5-to-7 years for the first crop which can be unaffordable. The cultivation of palm oil is water-intensive: requiring a minimum of 280-to-350 liters of water per plant per day, which can be difficult to come by as irrigation infrastructure is poor. Agriculture in India is largely rain-fed and monsoons can be erratic, which also adds limitations as to where the crop can be grown. Growing palm oil at a scale where it can be profitable also requires large areas of land, which is problematic in a country riddled with small-holder farms. Domestic cultivation has raised concerns by environmentalists and conservationists about the impact of such monoculture on biodiversity, and the risk of groundwater depletion due to the crop’s water-intensive nature.

Given the right conditions, however, palm oil cultivation can be very lucrative, and grown in a sustainable manner. Professor Ashok Vishandass at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) claims that “4 million MT [metric tons] of traditional oils is being produced in the country by using 15.8 million hectares of land. This much quantity of palm oil could be produced from just 1 million hectares.” To encourage farmers in selected states identified for growing oil palm, the central government (as part of the National Food Security Mission) is working with state governments to provide financial incentives as well as technical and scientific support to increase efficiency yields. The Indian Institute of Oil Palm Research (IIOPR) serves as a center for conducting and coordinating research on all aspects of palm oil conservation, improvement, production, protection, post-harvest technology, and transfer of technology. In August 2021, under the National Mission on Oilseeds and Oil Palm (NMOOP), the Union Cabinet approved €1.27 billion to be spent over the next five years to make India more self-reliant.

As of July 2020, India had 330,000 hectares under palm oil cultivation in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Mizoram, Assam, Nagaland, Tripura, and Arunachal Pradesh, and a potential 1.93 million hectares have been identified for additional cultivation. Palm oil production in India increased by about 45% over the five-year period from 191,510 tons in 2014-2015 to 278,922 tons in 2018-2019.

The potential hazards and future risks to biodiversity when domestic production is scaled up further have not received extensive attention or adequate news coverage, as domestic production is nowhere close to meeting the steadily increasing demand for palm oil in India, while imports from Malaysia and Indonesia continue to be significant. Efforts to green the supply chain have also had limited uptake from industry: in 2017, the Solvent Extractor’s Association (SEA) released the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability Framework; and in 2004, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was formed as a voluntary organization whose members are meant to comply with a set of social and environmental norms. However, only an estimated 3% of India’s palm oil imports are RSPO-certified.

The Need for More Sustainable Solutions

Given India’s dependence on palm oil, the way forward to ensure more sustainable manufacture, as well as use, is complicated. Without viable alternatives, restricting imports will only result in increased illegal channels being used for procurement. Ramping up domestic production to meet demand, be financially viable for farmers, cultivated in areas where water tables are unaffected, and in a way that protects biodiversity, will require greater research and analysis, monitoring, and data collection. An explicit mapping at the national level will be helpful in understanding the land-use patterns, including protected areas, primary and secondary forests, agricultural land with crops, fallow lands, and degraded areas. Potential areas favorable to growing palm oil must then be identified by also considering climatic conditions, rainfall, water balance, biodiversity, and land profiles. Along with irrigation facilities, there must also be a mechanism to monitor and replenish water tables. Along with research on growing palm oil more sustainably, there is also a need for greater research and data on viable alternatives; while the coconut tree, which uses less water and can be grown along with other crops could be a solution, evidence on growing it sustainably in large quantities to meet demands is limited. Finally, there is also a need to increase knowledge and awareness about changing consumption patterns and manufacturing behaviors – maybe we don’t need so much palm oil.